Part 1 of this series was a summary of the ancient Indian economy. In this part, we shall look at the mediaeval economy of India, which began with the fall of the Gupta dynasty in the 7th century CE and finally culminated with the beginning of the Delhi Sultanate in the 13th century CE. This part also covers the important rise of Europe in dominating the world order through its colonial expansion and how it specifically impacted India too.

Understanding Indian Economy: Ancient To Modern – Part 2

You can read part 1 here.

MEDIAEVAL ECONOMY OF INDIA

The Early Period: 8th to 12th centuries CE

The Guptas and the Vardhanas, the last of the great Indian dynasties, collapsed by the 7th century CE. The period from the 8th to the 12th centuries CE, between the fall of the Guptas and the beginning of the Delhi Sultanate in the 13th century, had smaller kingdoms across the country. This period suffers from a lack of coins and written sources, which gets two opposite interpretations from economic historians: one as a dark period of stagnation and the other as the development of alternative forms of exchange.

The early mediaeval period saw a huge increase in land grants to feudatories and religious establishments across the country. The classical Marxist scholars subscribe to a model of economy marked by an Asiatic mode of production—a despotic model of stagnation. Feudalism because of land grants resulted in a decline in both urbanism and foreign trade. Centralised state authority broke up to give way to semi-independent rulers, allowing a situation of forced labour, petty officials, and a type of serfdom.

New theories, however, say the opposite and believe that Indian feudalism, unlike the European type, was perhaps non-existent. Conducive agricultural conditions for most of the year, the hump on the Indian bull preventing excessive human labour, and two-crops a year made India a ‘free peasant economy’. The dark period was more applicable to Europe, perhaps. BD Chattopadhyaya postulates a period of integration rather than disintegration, which led to the emergence of new states, the flourishing of trade, and new urban centers. This radically challenges the stereotypical Indian feudalism model, says Vipul Singh, author-historian (Interpreting Mediaeval India).

Another group of historians similarly argues for the assimilation of local polities into larger state structures. There could have been a period of flourishing trade urban centers developed at the sites of old towns, perhaps the period of the ‘Third Wave of Urbanization.’ Economic historian John Deyell says that the non-availability of coins could be a situation of increased demand and not a financial crisis. Cowries (shells) were the mode of exchange instead of silver coins, and there is evidence of using hundika as bills of exchange. There is also evidence of a flourishing trade with the Arab world, China, and Southeast Asia.

The Delhi Sultanate (The Late Medieval Period)

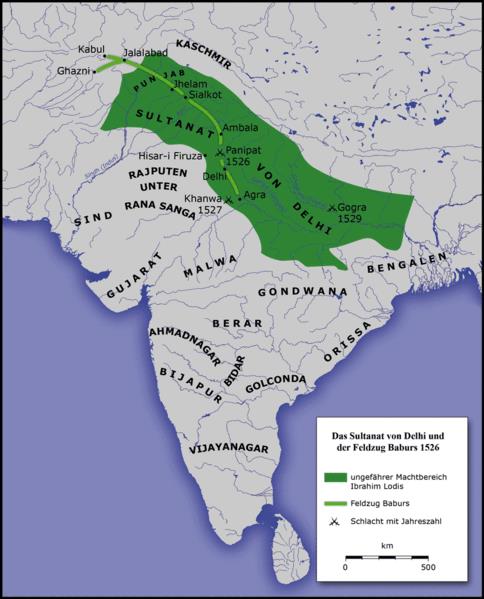

Mahmud Ghazni attacked the Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms from 962 CE to 1030 CE seventeen times but could not get a foothold. Muhammed Ghori finally started the Mamluk dynasty’s rule over Delhi. A total of 320 years from 1206 CE to 1526 CE was the period of five successive Islamic dynasties forming the Delhi Sultanate: Mamluks (1206–1290), Khiljis (1290–1320), Tughlaqs (1320–1414), Sayyids (1414–1451), and Lodis (1451–1526). In 1526, Babur defeated Ibrahim Lodi and began the Mughal Empire.

The Sultanate integrated India into a global cosmopolitan culture, gave some Hindu-Islamic syncretism, established a unique Indo-Islamic architecture, and could withstand the Mongols. However, it was disruptive too, with the destruction of temples, universities, and libraries. The area under its rule peaked during the Tughlaq dynasty. The economic policies included severe centralization of markets, tight controls, heavy taxes (up to 50% of agricultural produce), pricing controls, strict punishments, and licencing regulations. However, the disruption of social and political life did not grossly damage the economy. India’s GDP share of the world declined under the Delhi Sultanate from nearly 30% to 25% and would continue to decline until the mid-20th century. Papermaking became widespread during this period.

The Mughal Empire (1526-1857)- Socioeconomic Status

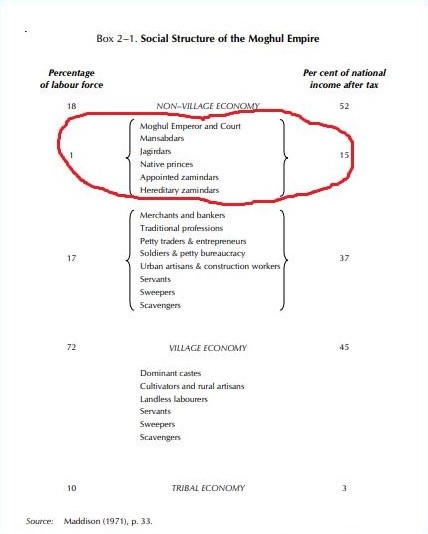

Muslim rulers, the ruling elite, from the thirteenth century until the British takeover squeezed a large surplus from a passive village society. The ruling Muslim elite was only 1 percent of the labour force, contributing to 15 percent of national income.

Urban artisans producing high-quality cotton textiles, silks, jewellery, decorative swords, and weapons, supplied the needs of the extravagant ruling class. The Moghul non-hereditary aristocracy had access to tax revenue from a specified area (a jagir). Influential secular historians propagate a rich Mughal India. Mughal architecture does suggest a rich economy, but there was no general prosperity in Mughal India, says Saumya Dey (Narrativizing Bharatvarsha). Mughal rule was the ruthless exploitation of the primary producers—theartisans and the peasants. The silver wage data unambiguously suggests the divergence between England and India for unskilled workers. Skilled workers could not have fared a lot better. European travellers such as Francois Bernier wrote about the harsh treatment of artisans and their poor payment by the nobility.

Irfan Habib (The Agrarian System of Mughal India) shows the sad plight of the peasantry in the Mughal Empire and its terrible oppression. The peasant was poor and debt-ridden despite increased agricultural produce. The diet and clothing of the rural populace were rudimentary. Famines were frequent. The land revenue levied in the Mughal Empire was steep, amounting to half the produce. The tax was high because two sets of people levied it: the jagirdars (who had to maintain expensive armies) and the imperial authorities (who approximated the surplus produce).

The jagirdars, transferred frequently, rarely had any long-term vision towards improving agrarian production. In the Mughal Empire at its peak (mid-17th century), in contrast to the rest of the world, commodity consumption in the Empire was heavily in favour of only the higher classes. In 1647, only 445 families received 61.5 percent of all revenues, which were about 50 percent of gross agricultural output. Mughal India was not ‘rich’; only the Mughal royalty and nobility were.

THE COLONIAL STORY OF EUROPE AND INDIA

European Nationalism and Colonialism Impacting the World

Some scholars do think that had the British and France not ruled India, it would not have developed as well from the ruins of the Mughal Empire. However, there was a certain unjustifiable moral and ethical deficiency in the European alteration of the world in the name of nationalism. The violent European domination against other parts of the world involved extermination, marginalisation, the conquest of indigenous populations, slave trade, colonisation, material loot, and intellectual plundering of societies.

Angus Maddison (The World Economy) shows how Europe declined economically from the first to the tenth centuries but forged ahead in the next five hundred years. A few major reasons for its growth were improvements and growth in agricultural methods, international trade (sugar, spices, paper, silk), mining, metallurgy, weapons production, shipping, navigation techniques, banking, accountancy, marine insurance, universities, printing, and windmill technologies. The beginnings of the nation-state system also helped.

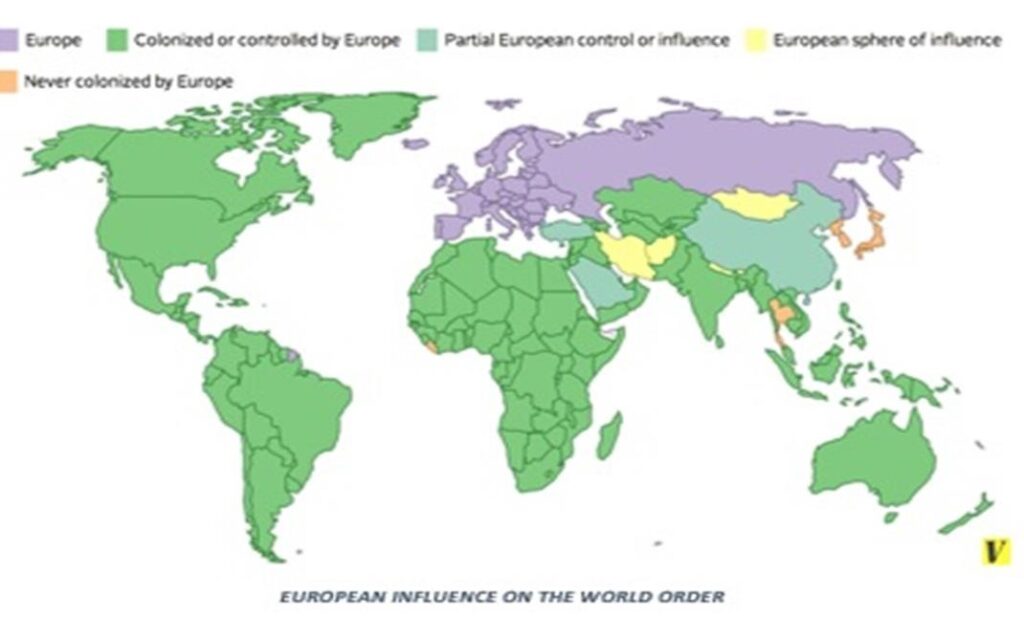

European colonialism, from the 16th to 20th centuries, led to the establishment of colonies in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Europeans, with relatively scarce trade resources, but hugely equipped with guile, military resources, nationalistic zeal, and decrees from royalty and the Church; travelled widely to occupy foreign lands. The academics at the universities gave intellectual justifications for these excursions.

Colonialism was of two types:

1) settler colonialism, when primarily European residents established towns and cities (United States, New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, Argentina, and Australia); and

2) exploitative colonialism, purely extractive and exploitative colonies. When Europeans settled in desirable territories, natives gave way to the colonialists, mostly in a violent manner.

The saddest chapter was arguably Africa. The Berlin Conference of 1884 allowed European states with even the most tenuous connection to an African region to claim dominion over its land, resources, and people. It allowed the arbitrary construction of sovereign borders that had never previously existed. During the colonial period, the British and the French colonised more than 95% of the continent. The entry of the Germans, Portuguese, Italians, and Dutch led to the spread of European culture. Today, most of Africa uses either French or English as the second language. The extreme economic exploitation of Africa included the slave trade, one of the most brutal chapters of human history.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Britain, the main slave shipper, brought a total of 2.5 million Africans to the Americas. The British abolished the slave trade and slavery by 1833, with £20 million compensation to slaveowners and nothing to the slaves. The table (Maddison) shows starkly the impact of colonisation on the US, with a decrease in Indigenous population, a migration of Europeans, and a thriving slave trade.

| Ethnic Composition of the US Population, 1700–1820 (in 000) | |||||

| Indigenous | White | Black | Total | ||

| 1700 | 750 | 223 | 27 | 1000 | |

| 1820 | 325 | 7884 | 1772 | 9981 | |

The English and the Other Europeans

The Dutch (Netherlands) had a huge presence across the world, constantly fighting the Portuguese and the British, and finally losing many territories. The Dutch, between 1636 and 1658, ousted the Portuguese from Ceylon and made it a major Dutch trading post. Later, in 1796, the British seized control of the Dutch positions. The Dutch replaced the Portuguese in Indonesia, which became the headquarters of the Dutch East Indies Company. The Dutch had bases in Taiwan, Malaysia, Japan, Australia, Iran, Pakistan, Ghana, South Africa, the present-day USA, the West Indies, Suriname, Guyana, Brazil, the Virgin Islands, and Tobago, amazingly.

The British invaded almost 90 percent of the countries around the globe at different times. Only 22 of the almost 200 countries in the world have never experienced an invasion by the British. Between 1700 and 1820, Britain rose to world commercial hegemony due to many reasons: changes in British economic structure with a big rise in industry and services; use of a beggar-your-neighbour strategy; and wars that weakened French and Spanish domination. Though it lost the Americas, it extended its control over India. Britain grew further between 1820 and 1913 due to technical progress, absent wars, the growth of the physical capital stock, and improved education and skills in the labour force. It added Africa, Asia, and a major part of India from 1820 to 1913. The total population of the Empire was 412 million (ten times Britain’s size), and three-quarters of this was from India.

Small countries could colonise too. Denmark-Norway had colonies in Africa, the Caribbean, and India (Tranquebar in 1620). Belgium controlled the Belgian Congo from 1908 to 1960 (76 times larger than Belgium itself) and Ruanda-Urundi from 1922 to 1962. Spain had conquests in the Americas and Africa. Portugal had large areas of control in Brazil, Africa, South-East Asia, and, of course, an uninterrupted four-and-a-half-century hold over Goa. Italian colonialism (1890–1941) in Africa included Libya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia.

Switzerland, the only paradox, did not colonise any country but did have connections through mercenaries, businesspeople involved in the slave trade, and a widespread network of missionaries. The Swiss turned English colonial expansion to their own advantage. They rose to the top economically through a combination of many factors: avoiding confrontation with the English; producing high-quality goods; maintaining a state of armed neutrality; offering economic concessions to parties on both sides of the war; production facilities remaining undamaged by the war; and the absence of patent law until 1907; which facilitated the emergence of many industries at low development costs. Swiss neutrality, political stability, national sovereignty, and ‘no questions asked’ banking have allowed the most prosperous banking sector to grow. Today, an estimated 28 percent of all funds held outside the country of origin are in Swiss banks.

In the period between 1913 and 1950, the two world wars and the Great Depression shattered the liberal economic order. International migration grossly came down; foreign assets were sold, seized, or destroyed; and overseas empires disintegrated, yet their impact on world economic growth was smaller than expected. The pace of technological advances (transport revolution; road freight transport; tractors; aviation; electricity; automobiles; a huge range of new household products, and so on) was responsible for this. There were also advances in chemistry, which created synthetic materials, fertilisers, and pharmaceuticals.

Colonial India- A Snapshot

The colonial expansion of many European nations, made possible by a few decades of advanced naval power and a sense of religious, intellectual, and racial superiority, deeply impacted India. The British fought 111 wars to capture India, according to one count. Samuel Harrington says,

“The West won the world not by superiority of its ideas, values, or religion, but rather by its superiority in applying organised violence.”

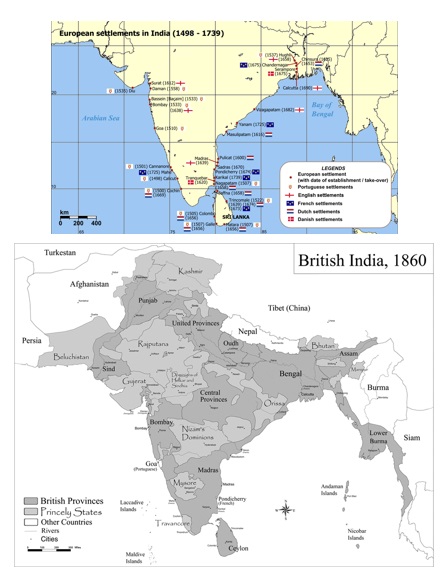

The European naval power used the trade route with India and East Asian countries by sailing around Africa (before the Suez Canal) for colonial expansion starting in the 15th century. Trading rivalries among the seafaring Europeans brought them to India.

The Dutch (1605–1825), the Danes (1620–1869), the French (1668–1954), the Portuguese(1505–1961), and the British (1612–1947) had a piece of India at various times. They militarily fought amongst themselves on Indian soil, and finally the British emerged victorious. The South Indians and the Marathas were great naval warriors, resisting the Europeans and sometimes defeating them badly. Marthanda Verma (1705–1758), a great Kerala ruler, resisted the Dutch and defeated them decisively. Some claim that if this had not happened, India would have been using the Dutch language instead of English today.

European internal wars and treaties influenced India. The most significant would have to be in 1661, when Portugal, at war with Spain, needed assistance from England. This led to the marriage of Princess Catherine of Portugal to Charles II of England, who imposed a dowry that included southern Bombay. This was a major event for Britain, which kicked off their conquests vigorously. With the disintegration of the Mughal Empire in the early 18th century and the weakening of the Maratha Empire after the third battle of Panipat (1761), many relatively weak and unstable Indian states were increasingly open to manipulation by the Europeans.

In the later 18th century, Britain and France struggled for dominance, partly through proxy Indian rulers but also by direct military intervention. The Deccan wars between the French and the English had Indian soldiers on both sides. By the middle of the 19th century, the British had already gained direct or indirect control over almost all of India.

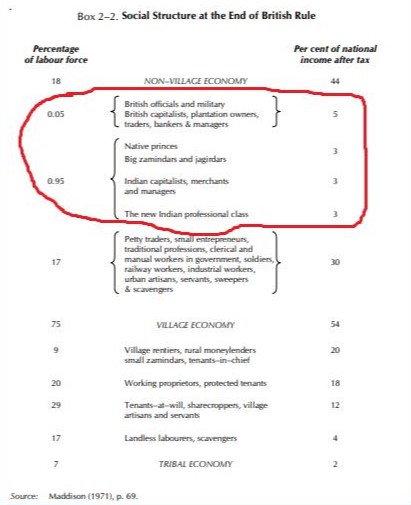

In 1600, Britain contributed 1.8% of the world GDP when the East India Company was set up. In 1750, India and China constituted 75% of the world’s GDP. When Britain left India, the former was contributing 10% of the world GDP, and India a pathetic 1.8%. The British left behind a society with 16% literacy, a life expectancy of 27 years, and over 90% living below the poverty line. Electricity, first supplied in the 1890s, reached all of Britain, the US, and Europe by 1947. However, merely 1500 of India’s 640,000 villages were on the electricity grid.

India was an ‘extractive colony’. India’s rich maritime trade and advanced banking system came to a grinding halt under colonial rule. The British Raj systematically subverted each of the state machinery tools, such as armies, censuses, bureaucracies, railroads, hospitals, telegrams, and scientific institutions, to its own profit by plunder and manipulation. As Shashi Tharoor (An Empire of Darkness) explicitly states, in the 107 years from 1793 to 1900, an estimated 5 million people died the world over in all the wars combined. But, in only 10 years, 1891–1900, 19 million people died in India due to famines alone. The famines, the biggest colonial holocausts, are at the top of some of the most severe inhumanities in modern times.

The regular Bengal famines were the result of careless planning, Malthusian ideas, and highly racist leaders sitting in England looking the other way. Churchill hated the Indians and thought that they bred like animals. While the people were reeling under famines, rice went as an export from Bengal to feed the soldiers fighting the World War in Europe. Madhushree Mukherjee, in her book, Churchill’s Secret War, details with deep research the role of Churchill in the Bengal famine of 1943, which killed 4 million Indians. This was a crime that puts Churchill on the same pedestal as Hitler.

It is difficult to place a figure, but on an estimate, the British took 45 trillion dollars from India during their 175-year presence (Utsa Patnaik). Of course, there are disagreements about this figure between the apologists and the history-reclaimers, who believe that this figure is an oft repeated myth. Finally, the British, apart from the economic plunder, distorted our cultural-social narratives, which we completely internalised. The British left a bifurcated country, but the discourses they left behind (religions, caste system, Aryan theory, and so on) continue to divide us in many ways.

The Portuguese, a story most Indians are simply ignorant about, ruled Goa for a continuous period of more than four centuries (1510–1961). They blatantly refused to let go of it, even after Indian independence. An army attack, finally led by the Indian government, made them flee without much bloodshed. Ironically, Portugal was and continues to be one of the most backward countries in western Europe. Yet, it was a ‘pioneer in expansionism’, motivating other seafaring and shipbuilding neighbours to explore, conquer, and plunder. Agriculture, infrastructure, industry, and higher education stayed quite static in Goa, as Portugal did not make any great attempts at boosting them. Excise duty was a great source of income. Banco Nacional Ultamarino, the only bank, had the dubious distinction of accepting deposits but offering no interest and advancing loans at the highest rate of interest in the world. Portugal just did not know how to exploit India as effectively as the British!

India And the World Wars – Fighting Without Stakes

The First World War (1914–1918), involving 32 countries, divided Europe into two coalitions: the Triple Entente, or Allied Powers (France, Russia, and Britain), and the Triple Alliance, or Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy). The mobilisation of 70 million military personnel made it one of the largest wars in history. An estimated nine million combatants and seven million civilians died as a direct result of the war.

In 1914, the Indian Army was one of the two largest volunteer armies in the world. The Indian Army fought in the North-West Frontier, Egypt, Singapore, and China. The Indian Army also fought in the European, Mediterranean, and Middle East theatres of war. Over one million Indian troops served overseas, of whom 62,000 died and another 67,000 wounded, a war without any personal stake or honour, except for the reason that we were a colony of the British. 588,717 Indians went to Mesopotamia, 116,159 to Egypt, 131,496 to France, 47,000 to East Africa, 4,000 to Gallipoli, 5,000 to Salonica, 20,000 to Aden, and around 30,000 to the Persian Gulf to fight in World War I for the British.

The Second World War (1939–1945) was the deadliest conflict in human history, with 50–85 million fatalities. This war, involving almost 50 countries, included massacres, the genocide of the Holocaust, strategic bombing, premeditated death from starvation and disease, and the only use of nuclear weapons in war. It began with the invasion of Poland by Germany and subsequent declarations of war on Germany. It was a fight between the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, Japan, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria) and the Allied powers (U.S., Britain, France, USSR, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Denmark, Greece, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, South Africa, and Yugoslavia).

2,065,554 Indian soldiers fought in the Second World War, and over 87,000 Indian soldiers died in World War II. Indians fought in the European theatre against Germany; in North Africa against Germany and Italy; in the South Asian region, defending India against the Japanese; and fighting the Japanese in Burma. Indians also aided in liberating British colonies such as Singapore and Hong Kong after the Japanese surrender in August 1945. Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army, said that the British ‘couldn’t have come through both wars if they hadn’t had the Indian Army.’ Basically, India fought and lost its sons in a war essentially based on the greed, ambitions, and angers of European powers against each other. This is the briefest description of the main historical events that impacted our economy.

In the next part, we shall look specifically at British rule in India and how it impacted the Indian economy. Ironically, this is also a major point of contention, as there are strong voices that do not agree that the British were an unmitigated disaster for India. A study of the British impact on the economy was in fact one of the great initiators in the field of economic history in India.

.…Continued in part 3.

You can read part 1 here.

Leave a Reply