Dr. Pingali Gopal recaps Sri Aurobindo's life, views and works; and argues that his teachings be an integral part of Indian education.

Sri Aurobindo: A Broad Overview Of The Greatest Visionary

Sri Aurobindo — Yogi, philosopher, freedom fighter, nationalist, and humanist, is one of the most important figures in modern India. His vision and love for India and humanity as a whole should have made Sri Aurobindo mandatory reading for every Indian. Sadly, independent India ignored him. The ideals of Sri Aurobindo would have formed a better foundation for a new India. David Frawley says:

“With due respect to Gandhi and his efforts, Sri Aurobindo provided a more profound Yogic view of India and a more practical view of strength and leadership for the country.”

Similarly, historian R. C. Majumdar writes:

“Arabinda had a much clearer idea as to what should be the future politics of India than most of its leaders who shaped her destiny.”

Sri Aurobindo remains a vaguely known figure in the collective Indian psyche. Born on August 15, 1872, he had his early education in Darjeeling and left for England at the age of seven. He graduated from Cambridge University in 1890. He passed a tough Indian Civil Service Exam but did not show up for a horse-riding test, and hence the examiners disqualified him! Aurobindo, in 1893, at the age of 21 years, came back to India and joined the state service of Maharaja Gaekwad of Baroda, where he taught English and French. While at Baroda, he gradually got involved in the revolutionary movement. He used his extraordinary writing powers for a series of anti-colonial magazines like Indu Prakash, Bhawani Mandir, and Bande Mataram. In 1906, he shifted to Calcutta to become the principal of the newly opened Bengal National College. He later became the editor of Bande Mataram.

He finally settled in the French colony of Pondicherry to escape the persecution by the British in 1910. His sadhana for spiritual work and writings took a greater and bigger turn. A phenomenal amount of writing happened during his stay in Pondicherry, where he used to go into a protracted period of silence. Arguably, we have yet to see more powerful writing in English than Sri Aurobindo’s. One might even be right to think that the divine shines through in his writings.

Despite focusing on spiritual sadhana, he still wrote about political issues, as he remained connected with contemporary politics. On his 75th birthday, in 1947, India finally gained its independence. He, of course, was unhappy with India’s state and pleaded for extreme caution in building the future. In 1950, Sri Aurobindo left his physical body.

SRI AUROBINDO AS A FREEDOM FIGHTER

The Critical Event of 1905: The Partition of Bengal

An extremely critical event in the independence movement was the partition of Bengal in 1905 based on Hindu and Muslim identities by Lord Curzon. Though it was for ‘administrative convenience’ officially, the intention was to divide India into two separate religious groups. Sri Aurobindo was at the forefront of an intellectual revolt against the British, based on the twin concepts of boycott (for all British goods) and Swadeshi (for only indigenous produce). It later imbibed other principles, like a National Education Policy. The movement spread from Bengal into the national scene (Punjab, Maharashtra, Madras, Gujarat). 1905 is a landmark year for both our journey to independence and Pakistan’s formation. People like Aurobindo and Tagore provided intellectual support. The clarion call was, of course, Bankim Chandra’s Bande Mataram.

Sri Aurobindo forcefully enunciated the principles of this passive resistance. It is important to note that, writing for Bande Mataram, he laid the ideals of Swaraj, Swadeshi, and the doctrine of passive resistance at least a decade before Gandhi. The British arrested Sri Aurobindo for alleged seditious writings in 1907 but later released him for lack of evidence. He was a key member of the Nationalist Party of the Congress and stood in opposition to the Moderate Congress group, led by leaders such as Gopal Krishna Gokhale. The Nationalists accused the Moderates of an ineffective method of ‘pleas, prayers, and petitions.’ Finally, the Nationalist Party broke away from the Moderates in a very stormy Surat session. The British again arrested Sri Aurobindo in the Alipore Bomb case in 1908, and he had to spend a year in jail. It was here that he had a deep spiritual experience.

The Passive Resistance Doctrine

Sri Aurobindo, in 1907, published in Bande Mataram a series of extremely powerful articles that presented the doctrine of ‘passive resistance’ or ‘defensive resistance’. He wrote that there were only three policies for freedom:

1) petitioning, a sure-to-fail way;

2) self-development and self-help (which he advocated); and

3) the orthodox historical method of organised resistance (which has a place when everything else fails).

Reacting to the criticism that India was unfit for self-rule, he wrote,

“Political freedom is the life-breath of a nation; to attempt social reform, educational reform, industrial expansion, or the moral improvement of the race without aiming first and foremost at political freedom, is the very height of ignorance and futility…”

Aurobindo more than amply clarifies that the advocates of defensive resistance were no extremists and were trying to give the country its last chance of escaping the necessity of extremism. For Sri Aurobindo, passive resistance was the only effective means, but where the denial of liberty was violent, the answer to violence with violence remained justified and inevitable.

In an important essay, The Morality of Boycott, he deeply explains the fundamentals of the Swadeshi movement:

- The expansion of indigenous industries allows for industrial boycotts.

- Indigenous arbitration courts would prevent foreign justice courts from entering Indian social and cultural life.

- Indigenous schools would impart national education in a vernacular language, preventing the influence of the English education system and values.

Finally, this would culminate in a refusal to pay taxes. In this essay, he strongly critiques people who condemn aggressiveness. This article, though unpublished, became evidence against him in the Alipore Conspiracy Case (1908).

Sri Aurobindo On Gandhiji and The Congress

Though holding nothing against the individuals, Sri Aurobindo was critical of both Gandhiji’s and the Congress’s dealings with the British as well as the Muslim League. Aurobindo thought that when dealing with the British, Gandhiji and the Congress never pushed for a hard bargain, while their dealings with the Muslim League were characterised by appeasement and a disregard for history. Supporting the Allied forces openly during the Second World War as a Dharmic righteous war, he had no patience with Gandhian principles of non-violence against an asura like Hitler.

He severely criticises Gandhiji for his support of the Khilafat agitation in 1921, which further led the way for the Hindu-Muslim divide culminating in Pakistan. He was also critical of Gandhiji’s support of Nehru instead of Patel as the first Prime Minister in 1947, against the wishes of the Congress Committee. Harshly prophetic, Sri Aurobindo tells his disciples.

“Gandhiji would have no relevance for a future India. When Gandhi’s movement started, I said that this movement would lead either to a fiasco or to great confusion. And I see no reason to change my opinion. Only I would like to add that it has led to both.”

His harsh criticism of Gandhiji’s policies was one possible reason why our history and social sciences obliterated him. For Sri Aurobindo, ahimsa, or non-violence, was a method of inner spiritual transformation. It was weak and ineffective as a weapon against dominating powers, but it could call for some concessions at best, as happened with the Satyagraha struggle in South Africa. Ahimsa is not the Dharma of the Kshatriya, who will lay down his life and even use violent means to protect what is the truth. Thus, ahimsa serves as a spiritual quality for the inner transformation of an individual. It could never be the guiding ideal of a nation grappling with a multitude of internal and external issues.

The Cripps Mission and The Second World War

In 1942, Sir Stafford Cripps arrived in India to seek Indian support for World War II efforts. In return, they promised to grant India dominion status after the war. The Congress rejected it outright, but Sri Aurobindo wrote desperate letters to all leaders, urging the Congress to accept the proposal with both hands. Gandhiji, irritated, thought that Sri Aurobindo was unnecessarily interfering in the country’s politics. Later scholars and many Congress leaders held the well-known view that had the Cripps mission succeeded, the partition would have never happened.

In 1921, BC Chatterjee published a book (Gandhi and Aurobindo) in which he compared the political ideologies of the two great personalities. He is respectful to Gandhiji but favours Sri Aurobindo. He writes that politics is the relationship between man and man — an imperfection with another imperfection — while spirituality is the relationship between man and God — an imperfection with perfection. One cannot apply Gandhi’s spirituality to such practical matters as politics. There are other kinds of spirituality for world humanism and internationalism, but the principles are radically different.

Sri Aurobindo wrote extensively during this period. He openly supported the Allied forces. For him, Dharma included the duty of a righteous war — the Kshatriya Dharma of Arjuna. He wrote that it was not that Britishers or Americans were angels, but that Hitler and Nazism represented the worst threat to humanity and the Earth. He had no patience with Gandhi’s non-violence formula, in which he asked the British to allow Germany to peacefully conquer them and the Jews to accept killing by anti-Semites as a supreme act of non-violence. Sri Aurobindo was also extremely critical of Subhash Bose, who used the Axis powers — the Germans and the Japanese — to fight the British. Eventually, he fully accepted Subash Bose’s patriotism.

INTEGRAL YOGA AND EVOLUTION

When Darwin created a ruckus in the religious world, Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo freely accepted the evolution of matter and life, and the latter made it a part of his Integral Yoga. This was not something radical, as Swami Vivekananda insisted, but simply in agreement with the principles of Vedanta. For Sri Aurobindo, matter, life, and mind were essential steps in evolution. But he does not stop there. The next steps in evolution were the Overmind, the Supermind, and the Saccidananda. The last was the highest ideal to realise and the pinnacle of evolution.

Every person had the potential to realise these higher states through knowledge, effort, and Sadhana. Sri Aurobindo also brings in the ideas of ‘Involution’ (a downward movement) and ‘Evolution’ (an upward movement). Swami Vivekananda also mentioned these concepts in his writings, but Aurobindo further elaborated on them. Involution is the delight of Saccidananda, or Brahman, plunging or degenerating into the realm of ignorance to create the world. Evolution is Brahman’s homecoming from the bottom level of inert matter. Hence, involution precedes evolution, and understanding them together is important in Aurobindo’s philosophy.

The scientific view does not give evolution any purpose, meaning, or direction. Swami Vivekananda and Aurobindo’s evolution are included in a broader framework of spirituality. For Aurobindo, evolution becomes a conscious movement, at least from the mind onward. Some contemporary biologists, like Eva Jablonka and Marion Lamb (Evolution in Four Dimensions), compellingly argue for a purpose and direction for evolution after a certain stage, negating the hard scientific views of people like Richard Dawkins. Sri Aurobindo is perhaps a visionary here.

Aurobindo’s view of evolution was deeply rooted in the Upanishidic wisdom. Most importantly, he had no problems with the prevailing scientific view of those times. Unfortunately, the definition of all ‘religious’ resistance is based on what the Abrahamic religions felt about evolution. Most scientists then and now, barring a few, are completely ignorant about the dharmic view of evolution. If only Western scientists and authors understood what Aurobindo and Swami Vivekananda wrote on evolution before widely condemning “religion” as standing in the way of “science.”

This contrasts with the Abrahamic religions, where science was in constant clash with religion (think Bruno and Galileo), and many times, the scientists compromised to avoid a clash with the church. The conflicting process continues in the Western world, nowhere more prominent than in evolutionary science. Even today, the United States has trouble teaching evolution. Disturbing voices still want alternatives to Darwinism taught in schools — intelligent design or its older form, God. As late as 1996, the Pope issued a statement in support of evolution.

Way back in the last decade of the nineteenth century, when Darwinism was peaking in controversy, Swami Vivekananda simply wondered what the fuss was all about. Advaita never had problems with evolution, and it is in fact a necessity of matter, he said. Religion is, in fact, the biggest supporter of evolution if one understands both correctly, Vivekananda claimed.

THE VEDAS, DRAVIDIAN IDENTITY, AND TAMIL

Sri Aurobindo emphasised self-study and not blind faith in the discovery of truth on an individual basis. An independent study of the Vedas finally crystallised into a wonderful book, The Secret of the Veda. It is a must-read for every Indian to realise how the Vedas form the absolute metaphysical bedrock of our culture and civilization.

Indologists have brutally assaulted the Vedas with their freewheeling interpretations, wild speculations, and assumptions. Sri Aurobindo completely trashes Max Mueller, philologists, and Indologists, showing how they missed the mark in understanding the Vedas. His prescient scholarship holds true even for the latest edition of the supposedly most authoritative Rigveda translation by Jamison and Brereton. In the framework of Sri Aurobindo’s understanding, Jamison and Brereton’s translation is simply an epistemic act of violence against Indian culture, heritage, and texts.

In The Secret of the Veda, Sri Aurobindo trashes the idea of an Aryan invasion and the separate racial identity of the so-called Dravidians. He also finds that the distinction between Sanskrit and Tamil was more a false construction than actual reality. It was more appropriate to think that they were both offshoots of one common language rather than two distinct languages. In a compelling manner, he deconstructs the dubious Aryan-Dravidian story. He demonstrates that, both by way of culture and language, Tamilians and Tamils belong to the same matrix of Indian culture. The idea of a divide between the Northern Aryans and Southern Dravidians was simply wrong.

People may not realise it, but the divisive Aryan-Dravidian theory is the fundamental root of all divisive narratives in the country. Sri Aurobindo was amused by the Aryan invasion theory, the Aryan-Dravidian divide, and a separate Tamil identity. Intellectuals of that era (like Dr. Ambedkar) seriously questioned the obnoxious theory, and they received considerable support from the archaeological excavations of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro years before independence. But most Indians, even today, have simply internalised the Aryan fantasy, with some deplorable consequences. The evidence for the Aryan invasion remains weak. If any, there is more evidence of migrations from India to other countries (the OIT, or Out of India Theory); but that is another story. Today, most of the divisive social narratives breaking out in India concerning tribals, the Dravidian movements, and Dalits rest on the pernicious Aryan theory.

ON POLITICAL SYSTEMS AND ECONOMY

Sri Aurobindo was critical of both European democracy and Russian socialism’s parliamentary systems. India had its own ethos, and it needed to chart a path based on Dharmic principles. The root of India’s future is our spiritual heritage, and on this, there was no compromise on his stand. Aurobindo had specific ideas about how to administer India, which was in danger of collapsing if not managed well. Sadly, a false notion of secularism and shunning everything that has shaped our national character for thousands of years has allowed for the present state of degeneration. Ananda Coomaraswamy wrote the same thing. Aurobindo foresaw corruption, goonda-raj, and a confused Indian identity many years before we even got our independence.

Sri Aurobindo was critical of the Westminster model of parliamentary party-based governments, stating that it was unsuitable for India. He was uncomfortable with the European idea of the nation-state, which he thought was only a forced political unity that was fragile in nature. The risk of such nation-states and their consequent nationalism was obvious during colonial expansions and world wars. For Aurobindo, political unification was secondary to another deeper form of unity already existing in India. Tagore also wrote extensively on similar lines as to how the Western notions of nations and nationhood led to severe problems in understanding the nationhood of India.

A Nation Is Not a Political Unit

Sri Aurobindo saw a nation as true unity rather than an empire, which is political unity. Political unity is utterly destructible. A nation, on the lines defined by Sri Aurobindo, is the “living group-unit of humanity,” from which appears internationalism too. The spiritual and cultural unity made India a civilizational nation-state. India does not fit into Western models of nations based on homogenization of language, religion, or some narrow cultural notion. For India, diversity is the basis. For the West, diversity is an anathema that needs explanation, said Aurobindo.

Sri Aurobindo knew that the Indian conceptions of a nation were spiritual and civilizational unity. Spirituality was the basis of any Indian field (arts, literature, music, dance, drama, sciences, economics, social life, and politics). India’s spiritual message was the most universal. Overall, the Self (or the Brahman of Advaita) was the true basis for the unity of all individuals in the nation, as was internationalism. Ananda Coomaraswamy also wrote that the Self in All was the basis of Indian metaphysics, and he insisted that this message should be an integral part of Indian education right from the beginning. Unfortunately, the labelling of Indian philosophies, or darshanas, as ‘religion’ and then excluding them from school and college education in the name of secularism was the biggest injustice done to our culture.

Countering the Enlightenment Narrative: The Past as a Solution

Both Sri Aurobindo and Gandhiji looked at our past as a solution for the future. For Gandhiji, the past was simple and clear, and the future was ‘advanced, complex, but evil.’ This partly explains his ‘return to the villages’ as a solution and his anti-industrialization stand. Sri Aurobindo held the Indic idea of a cyclical history, where the past did not equate to primitive and simple; it could equally be complex or advanced and hold solutions for all times.

In direct contrast to the Western ideas of enlightenment, Sri Aurobindo writes of three chronological phases of cultural India. He writes that India, unlike other civilizations, started at the highest levels of the Vedas and Upanishads. Then came a period of shastras, in which every material aspect of the world became a route to the highest (the spiritualization of the material). The third phase was the period of degeneration. For Aurobindo, a return to the past did not mean a return to the primitive. Thus, neither industrialization nor “modernity” spelled disaster the way it did for Gandhiji. Sri Aurobindo says,

“The past should be a guide and not a fossilised permanent step in the individual journey to Divinity.”

Thus,

“If questioning the past is wicked, then even Adi Shankara was wicked too!”

Cycles of Nation and Decentralisation with Villages Holding the Key

Sri Aurobindo, in The Ideal of Human Unity, describes the development of nations in cycles. In the first cycle, a local unit overshoots the regional and national units to become an imperial body. There is a forced unity among the other local units. The second cycle has three successive intermediate stages: a) feudalism; b) the grip of absolute sovereign authority, namely the King; and c) finally, the Church. The third cycle tends to be representative of the ‘whole conscious,’ be it individual or community, which absorbs all. This has strong roots in the minds of its citizens.

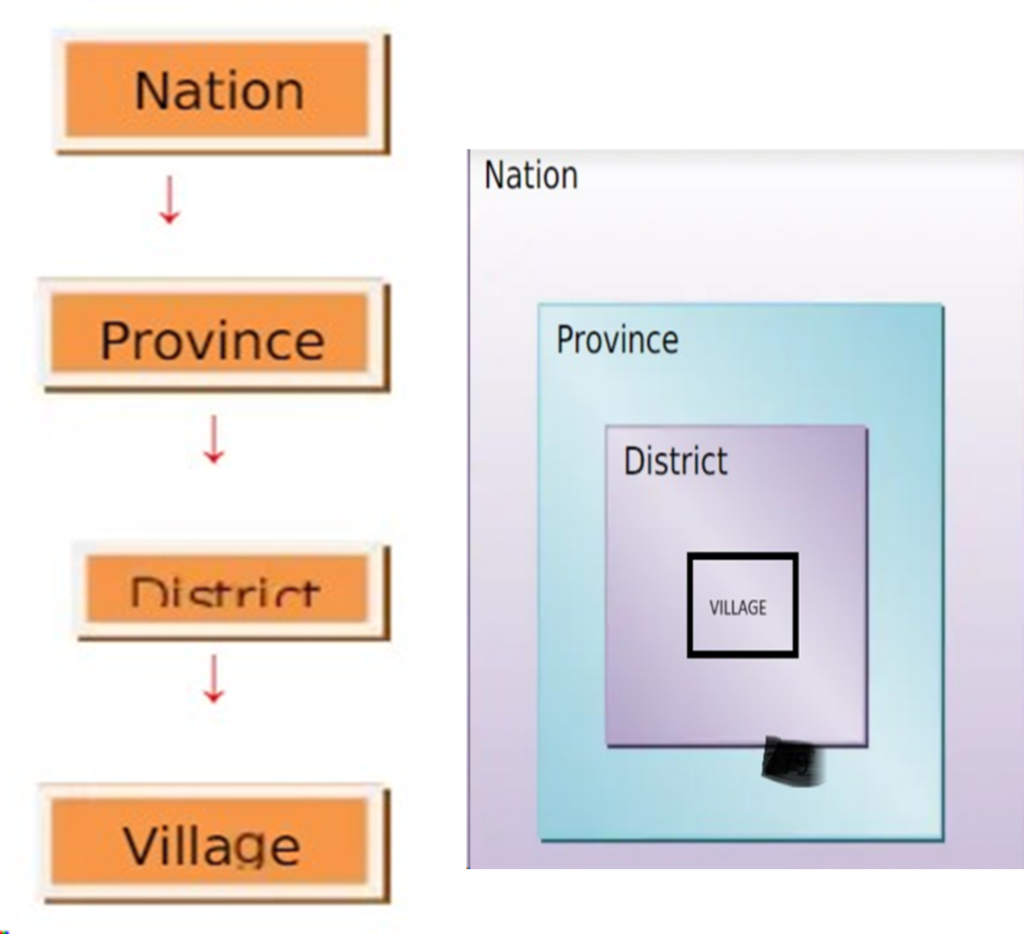

Decentralisation was the key to the political thinking of Sri Aurobindo. The subordinate parts merge into a stronger nation. Sri Aurobindo imagined an apex system of nation-building: nation (Rastra), state (Rajya), province (Pradesh), and village (Gram). Like Gandhiji, the village was central to nation-building. It was the nation’s basic unit, much like the human cell is to the body. Gandhiji, however, placed villages as an independent unit, with other units like districts, provinces, and the nation as larger surrounding circles. Aurobindo models an apex system with an independent yet dependent organic relationship between the primary unit and the higher organizations of complexity.

This graphic illustrates the general differences in thinking between Sri Aurobindo and Gandhiji. The actual ideas need greater study, of course.

Summing Up Sri Aurobindo’s Political Vision

Sri Aurobindo was in favour of a social democracy but was critical of the socialist way of criticising the capitalists. The capitalist class was a source of national wealth that needed encouragement to spend for the country. He said,

“Taxing is all right, but you must increase production, start new industries, and also raise the standard of living; without that, if you increase the taxes, there will be a state of depression.”

He was against both orthodox capitalism and socialism as the right solutions for the nation. He wrote that private enterprise by itself does not make society capitalistic. Similarly, a socialistic economy can admit some controlled private enterprise without ceasing to be socialistic.

Sri Aurobindo was consistently critical of politicians and political parties. He wrote of one Rashtrapati at the top with considerable powers to secure continuity of policy and an assembly representative of the nation. The provinces unite into a federation at the top, providing ample scope for local bodies to formulate laws tailored to their specific problems. Sri Aurobindo significantly says that Western politics conceives of doing away with political parties and creating governments of national unity only in times of war or crisis; India, because of her long tradition of unity underlying her diversity, should have shown that unity in diversity is not a freak phenomenon but a workable basis for new politics.

Michel Danino’s book Sri Aurobindo and India’s Rebirth is a fantastic resource for understanding Sri Aurobindo’s political views. In this book, Danino summarises the political vision of Sri Aurobindo for India. This included:

- To move away from party politics

- Simplification, decentralisation, local empowerment, true participation, ruthless transparency, and a suppleness that is responsive to evolving situations.

- Other institutions, such as the judiciary or bureaucracy, the penal system, and policing, would necessarily be part of this change, and their unwieldy structures, a source of misery rather than service to the common Indian, would have to undergo a major overhaul.

It is a tragedy of great proportions that post-independence India ignored him. Most educated Indians are only vaguely aware of him.

ON CASTE AND RELIGION

Sri Aurobindo significantly said,

“There is no doubt that the institution of caste has degenerated. It ceased to be determined by spiritual qualifications, which, once essential, have now come to be subordinate and even immaterial, and is determined by the purely material tests of occupation and birth. By this change, it has set itself against the fundamental tendency of Hinduism, which is to insist on the spiritual and subordinate the material…”

He wrote deeply about the caste system and warned against cheap denunciations of the varna-jati vyavastha based on distorted colonial and missionary narratives. The superimposition of the caste system, a Western idea reflecting classes, on Indian social systems caused much damage to Indian culture. He agreed that untouchability was a weed that needed uprooting, but to associate this phenomenon with the whole of Hinduism was mischievous and needed a strong rebuttal.

Like Ananda Coomaraswamy, he wrote that the strength of Indian civilization was in the three deeply interlinked quartets that prevented its disintegration: the four Varnas; the four ashramas; and the four purusharthas. Studying each in isolation leads to distortion, strife, and confusion, as is rampant today.

Sri Aurobindo was aware of the colonial narratives, which portrayed Buddhism as a separate religion from Hinduism. Buddhism was allegedly a revolt against tyrannical Brahmanical Hinduism, according to colonial-missionary writings. His most spirited rejection of this idea came when he said:

Buddhism seemed to reject all spiritual continuity with the Vedic religion. But this was after all less in reality than in appearance. The Buddhist ideal of Nirvana was no more than a sharply negative and exclusive statement of the highest Vedantic spiritual experience. The ethical system of the eightfold path taken as the way to release was an austere sublimation of the Vedic notion of the Right, Truth, and Law followed as the way to immortality, ṛtasya panthā. The strongest note of Mahayana Buddhism, its stress on universal compassion and fellow feeling was an ethical application of the spiritual unity which is the essential idea of Vedanta. The most characteristic tenets of the new discipline, Nirvana, and Karma could have been supported from the utterances of the Brahmanas and Upanishads. Buddhism could easily have claimed for itself a Vedic origin and the claim would have been no less valid than the Vedic ascription of the Sankhya philosophy and discipline with which it had some points of intimate alliance.

But what hurt Buddhism and determined in the end its rejection, was not its denial of a Vedic origin or authority, but the exclusive trenchancy of its intellectual, ethical, and spiritual positions. A result of an intense stress of the union of logical reason with the spiritualised mind — for it was by an intense spiritual seeking supported on a clear and hard rational thinking that it was born as a separate religion — its trenchant affirmations and still more exclusive negations could not be made sufficiently compatible with the native flexibility, many-sided susceptibility and rich synthetic turn of the Indian religious consciousness; it was a high creed but not plastic enough to hold the heart of the people. Indian religion absorbed all that it could of Buddhism, but rejected its exclusive positions and preserved the full line of its own continuity, casting back to the ancient Vedanta.

IMPORTANT SPEECHES AND ESSAYS

Each of his essays is the divine shining through. His writings, of incredible depth and breadth, are the result of a lifetime of study. A linguist with a grip on many classics of the Western world, his writings in English and Bangla were impeccable. As we read through his essays, we cannot help but feel a constant regret about how and why we missed him so much during our formative years. Whatever the topic, powerful ideas just emerged from his mind. As a result, he is one of India’s most important personalities and remains extremely relevant even now. He was indeed a great Yogi, a philosopher, a freedom fighter, and a nationalist. For those who want to taste his writing power, two speeches stand out, both of which are freely available. One of them is the Uttarapara Speech, which he delivers after his immediate release from the Alipore jail, fresh from a great spiritual experience. The second is his speech to All India Radio, which outlined his vision for the country at the time of India’s independence.

Uttarapara Speech

In this speech, he makes the clearest enunciation of Sanatana Dharma. He writes that India has always existed for humanity and not for herself, and it is for humanity and not for herself that she must be great. Expounding on Sanatana Dharma, he says that when one says that India shall rise, it is the Sanatana Dharma that shall rise. When the Sanatan Dharma declines, then the nation declines. He ends his message by saying that Sanatana Dharma is nationalism.

So, what is Sanatana Dharma? He says that this is the one religion that can triumph over materialism. It impresses on humanity the closeness of God to us, as well as all the possible means by which man can approach God. It is the only religion that consistently affirms that God is present everywhere and demonstrates that the world is the manifestation of Vasudeva’s Lila. And importantly, it is the one religion that does not separate life in the smallest detail from religion. It’s the only religion that knows what immortality is.

All India Radio Speech at Independence

This is a phenomenal message that shows happiness at independence while also warning India. Sri Aurobindo sees India as the spiritual centre leading the world towards a better future. India’s purpose was “… to live for God and the world as a helper and leader of the whole human race.” India marked a new era for humanity’s political, social, cultural, and spiritual future. India is free, but it should achieve unity first. The next step would be a resurgence of Asia to return to her key role in human civilization’s progress. He dreams of a world union that forms the outer foundation of a better life for all humanity. Finally, he dreams of an evolutionary step that would raise humans to a higher and larger consciousness. This would solve the most perplexing problem since the very beginning of humanity — to reach a state of individual perfection and a perfect society. This was the crux of Integral Yoga: a perfect individual and a perfect society.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Gandhiji’s writings consist of one hundred volumes, Sri Aurobindo thirty, and Swami Vivekananda nine. Sadly, only Gandhiji and Nehru fill our textbooks. They were indeed very worthy figures, but we had equally great figures, if not greater, in Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Swami Vivekananda, Tagore, Ananda Coomaraswamy, and Sri Aurobindo. Except for the Chicago address, we grew up knowing nothing about Swami Vivekananda, who had written extensively and remarkably about every aspect of India in his short life. In the case of Sri Aurobindo, an average Indian knows absolutely nothing, though he left us with a powerful set of writings that best explain everything about Indian culture, heritage, and social life.

Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo were also products of exclusive Western education, but their ideals and ideas were more in line with India’s traditional culture. They had a better understanding of the Indian past and clearly wanted it to be a solution for our future. The West espoused a linear enlightenment narrative, positing that the past equated to India’s primitive state. The West, or Europe, represented the future- advanced, and modern. Nehru rejected the Indian past, and the Gandhian ideal had contradictions with modernity.

Today, we see the phenomenon of deracination and derooting everywhere. SN Balagangadhara calls this ‘colonial consciousness.’ According to scholars at the Ghent School, most narratives about India have colonial roots. We have simply internalised many narratives set by the colonials without questioning them. Decolonization will take a lot of effort, but the first step is to at least recognise the problem. It is probable that we could have minimised the deracination had we included Sri Aurobindo in our curriculum. Sri Aurobindo had the clearest understanding of India — its past, present, and the ideal path for the future. It was a lost opportunity as an unfortunate rejection of traditional India and a fascination for the West became the basis for building our future.

Influential politicians, including the Prime Minister, with the task of building a new India at independence were Western-trained lawyers who almost rejected Indian traditions. The most tragic, arguably, would be an Islamic scholar serving as our education minister for almost a decade after independence. Politically, it was almost a suicidal mission for our rich traditional past, which had ample solutions to address modern India. Nothing could have been a bigger attack on Indian socio-cultural life than secularism, which Sri Aurobindo had amply warned against.

Over so many decades, our decolonization efforts have been less than half-hearted. As Michel Danino points out, India’s apparatus remained wedded to a British constitution, a British polity, a British judiciary, a British administration, and a British educational system — a prison that is about the antithesis of what Sri Aurobindo envisioned. Most importantly, secularism makes no sense in Indian culture. The separation of the “sacred” and the “profane” was a Christian Western idea relevant to a specific period of European Christendom. Transposing it as a solution to manage our communal problem between Hindus and Muslims is a tremendous recipe for disaster.

As Sri Aurobindo said,

“There is to me nothing secular; all human activity is for me a thing to be included in a complete spiritual life.”

Sri Aurobindo is deeply relevant to our country and our future. We need to study him in greater depth and detail. We should reintroduce Indian darshanas and people like Sri Aurobindo, Ananda Coomaraswamy, and Swami Vivekananda into our school and college curricula. Sri Aurobindo’s spirituality defined him, but it was not that of a renunciating monk. He was rooted firmly in the realities of the world around him, and India’s future worried him. Sri Aurobindo had an unclouded vision of India, and his most important message was that India’s future should be rooted in its ancient past. Traditional India is not as primitive as Western culture, backed by the power of modern technology, might tell us. The attempt to destroy traditions is the biggest debacle in independent India. As the great scholar Vishwa Adluri says, it is sometimes more important for traditions to question modernity from its standpoint.

For Sri Aurobindo, a blind aping of European ideals in terms of politics, administration, morals, ethics, law, and so on would be a recipe for disaster. We had a character of our own; we worked well over thousands of years solving our own problems, and there is no reason this could not happen in the future either. He said that foreign rule destroyed the shell, but the core remained intact and continues to hold solutions.

His assessment of Indian culture, its past, and its future was based on the spiritual essence of all living activities. Individual and collective returns to the spiritual essence were the basis for human unity, according to him. A material route to achieving unity would always be fragile and temporary.

SELECTED REFERENCES AND ADDITIONAL READINGS

- The History and Culture of the Indian People, Volume XI: Struggle for Freedom, by R. C. Majumdar

- The Morality of Boycott in Bande Mataram, Vol. 1: The Incarnate Word

- The Doctrine of Passive Resistance: Conclusions in Bande Mataram, vol. 1, The Incarnate Word

- Sri Aurobindo and India’s Rebirth (2018) by Michel Danino

- Gandhi and Aurobindo (1925), by BC Chatterjee

- The socio-political philosophy of Sri Aurobindo by Dr. Debashri R. Banerjee, Academia.edu

- The Spiritual Nationalism and Human Unity: An Approach Taken by Sri Aurobindo in Politics by Dr. Debashri R. Banerjee, Academia.edu

- Aurobindo’s Theory of Nation-State: Is It Contrary to the Saptanga Rastra Tattva of Ancient India by Dr. Debashri R. Banerjee, Academia.edu

- Social and Political Thought: The Human Cycle—The Ideal of Human Unity—War and Self-Determination, Sri Aurobindo’s Complete Works (The Incarnate Word), Volume 15

- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy: The Bugbear of Democracy, Freedom, and Equality in The Betrayal of Tradition, edited by Harry Oldmeadow

- Individuality, autonomy, and function in Anand Coomaraswamy’s The Dance of Shiva

- Religion and Spirituality in A Defence of Indian Culture, Sri Aurobindo’s Complete Works (The Incarnate Word) Vol. 14

- Hinduism and Buddhism (1943), by Ananda K. Coomaraswamy

- Mahatma Gandhi and Sri Aurobindo (2021), A Collection of Essays Edited by Ananta Kumar Giri

Leave a Reply