"Bridging the chasm between the historical Aurangzeb and this reimagined (and largely imaginary) Aurangzeb is a daunting task, but Truschke makes her case with the chirpy enthusiasm of an Aurangzeb fangirl writing a puff piece in People magazine on her idol.

The received historiography on Aurangzeb is riddled with outlandish hoaxes that have gone unchallenged for decades. Truschke’s book is a worthy addition to this genre since it refreshes our memories of these hoaxes while enthusiastically manufacturing new ones."

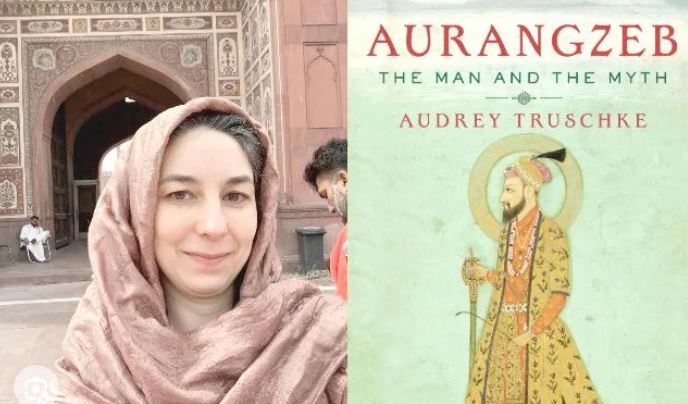

An incisive and witty review of Audrey Truschke's book on Aurangzeb, and her source material, by Keshav Pingali.

On Audrey Truschke’s “Aurangzeb: The Life and Legacy of India’s Most Controversial King”

In 1924, Sir Jadunath Sarkar completed his massive, five-volume “History of Aurangzib”. An expert in the Persian language, Sarkar wrote his 1,500-page manuscript after years of study of Mughal-era books, farmans, and other documents, copies of which he had acquired from all over the world, often at his own expense. In 1947, he translated from Persian to English the “Maasir-i-Alamgiri” (Khan 1985), an account of Aurangzeb’s life written by a Mughal official shortly after Aurangzeb’s death in 1707 A.D. (Sarkar 1947). By the time Sarkar passed away in 1958, he was one of the most famous historians in India and had written more than a dozen books; roughly half of them on Aurangzeb and his contemporaries such as Shivaji. Today, Jadunath Sarkar and his books are all but forgotten, perhaps because in our Internet age, no one reads 1,500-page history books, and even debates between intellectuals are carried out online in 280-character tweets.

To ensure that Aurangzeb is not forgotten like Jadunath Sarkar, Audrey Truschke, a professor in the South Asia Studies Program at the Newark campus of Rutgers University, has written a short biography of the great emperor (Truschke 2017). A little over 100 pages, the booklet narrates familiar events from its subject’s life, but Truschke’s more ambitious goal is to “reimagine” Aurangzeb and present him as a firm but loving ruler who devoted himself selflessly to the well-being of his, mostly Hindu, subjects. Bridging the chasm between the historical Aurangzeb and this reimagined (and largely imaginary) Aurangzeb is a daunting task, but Truschke makes her case with the chirpy enthusiasm of an Aurangzeb fangirl writing a puff piece in People magazine on her idol.

To get a sense for what passes for logic in this book, consider the non sequiturs in this paragraph.

“Also problematic is labeling Aurangzeb an orthodox Muslim – “an Abraham in India’s idol house,” to quote the Persian and Urdu poet Muhammad Iqbal (d. 1938). This framing suggests that Muslims are primarily defined by their faith and that Islam is fundamentally at odds with Hinduism. For India, such ideas mean that Muslims cannot be fully Indian…” (Truschke 2017, p.107).

The word “suggests” does a lot of heavy lifting in this book, letting Truschke pass off unwarranted inferences as profound conclusions. First, Aurangzeb’s religious beliefs have no obvious bearing on other people unless they explicitly model themselves after him. Second, all Abrahamic religions are “fundamentally at odds” not just with Hinduism but even with each other since none of them recognizes any other religion as a legitimate religion that leads to salvation. This fanaticism long predates Aurangzeb, and for that matter, Islam. Finally, Jews have thrived and practiced their religion freely in India for more than 2000 years, so there is no reason why people of other faiths cannot do so as well, even if like Judaism, these faiths are at odds with Hinduism. The gas chambers of Auschwitz are in Christian Europe, not India.

Elsewhere, Truschke makes this revealing comparison.

“Mughal rulers in general allowed their subjects great leeway—shockingly so compared to the draconian measures instituted by many European sovereigns of the era—to follow their own religious ideas and inclinations” (Truschke 2017, p.79).

In the 20th century alone, European thugs such as Leopold II, Hitler, Lenin, and Stalin, butchered tens of millions of innocent people, so it is quite possible that the Mughals were shockingly more tolerant than the European sovereigns of their age. They may also have been more tolerant than the headhunters of Papua and Guinea or the cannibalistic tribes of Equatorial Africa. In the Indian context, however, the relevant question is whether the Mughals were more tolerant of other religions than the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain kings who preceded them as rulers in India. For that matter, was Aurangzeb more tolerant of other religions than his great Hindu rival Shivaji? It does not occur to Truschke to ask these questions, perhaps because in her worldview, people of dharmic religions need to be ruled by others, and the only question is whether they are better off under Christians or Muslims.

It would take a book longer than Truschke’s to point out the many problems in her account of Aurangzeb’s life, so this article focuses on claims about Aurangzeb’s temple destruction and his patronization of Hindu and Jain temples, and makes three main points.

- Truschke’s claim that “Aurangzeb protected Hindu temples more often than he demolished them” is a re-engineered version of an earlier hoax by the Chicago scholar Lloyd Rudolph that is ubiquitous in the received historiography on Aurangzeb.

- The claim that temple destruction under Aurangzeb was “infrequent” and an “extreme measure” that was “used sparingly” is false even according to the sources cited in Truschke’s book.

- Most of the alleged farmans Truschke uses to “prove” Aurangzeb’s patronage of Hindu and Jain temples come from a single source named Jnan Chandra who was probably an imposter manufacturing farmans out of thin air.

Temple destructions

Claim:

“…. he [Aurangzeb] protected Hindu temples more often than he demolished them.” (Truschke 2017, p.79)

This claim is both provocative and memorable, and has received a lot of publicity in the Indian media. To evaluate it, we must ask; from whom Aurangzeb was protecting the Hindu temples. There were no foreign invasions during Aurangzeb’s reign (a threatened invasion from Persia never materialized), and restive Hindus like the Rajputs and Shivaji’s Marathas are not known to have destroyed temples. While a few temples may have been threatened by local Muslims, major threats requiring the intercession of the emperor could have come only from the Mughal administration. Aurangzeb though was an absolute monarch so his officials would not have threatened Hindu temples without his acquiescence. That leaves only Aurangzeb, and to say that he protected Hindu temples from himself is absurd unless there is reason to believe he suffered from multiple personality disorder, for which there is no evidence.

A more charitable interpretation of Truschke’s claim is that Aurangzeb destroyed fewer temples than he left standing. That is probably true since there must have been thousands of villages with small temples that he did not destroy, but this is akin to a Hitler fangirl praising the Fuehrer for protecting more Gypsies than he killed because there were still 750,000 Gypsies left alive in Europe after he was done killing 250,000 of them[1].

Nevertheless, Truschke’s remark about Aurangzeb is clever so I looked into how she might have come up with it. To my surprise, I found many papers published long before Truschke’s book that make the even more astonishing claim that “Aurangzeb built far more temples than he destroyed,” citing a paper by Barbara Metcalf to back up this assertion.

Metcalf is a South Asia scholar at the University of California, and a past president of the Association for Asian Studies (AAS). In 1995, she wrote a paper based on her Presidential Address at the 47th Annual Meeting of the AAS (Metcalf 1995) and in it, there is a footnote that reads,

“A lively debate ensued at the 1994 Boston meeting on this subject: Lloyd Rudolph noted that Aurangzeb, painted as the great destroyer of Hindu temples in the received historiography, in fact built far more temples than he destroyed.“

There is no citation to a publication by Lloyd Rudolph, so it is unclear how he reached this remarkable conclusion. Further investigation showed that the late Rudolph was a distinguished sociologist and economist at the University of Chicago, but he was not a historian, and I could not find anything he had published on Aurangzeb. Professor Metcalf replied graciously to an email enquiring about the same, as follows:

“I don’t know why I would have cited Lloyd — maybe a plug for the liveliness of AHA meetings! The late Lloyd Rudolph was a wonderful scholar but did not work on this topic himself to the best of my knowledge. And reading this fn [footnote] now, I’m not even sure about “built.” Maybe patronized? Certainly, there was a lot of patronage.” (July 17th, 2023)

Now we can trace the likely provenance of Truschke’s clever remark about Aurangzeb. At the 1994 meeting of the AAS, Lloyd Rudolph, who was not a historian, let alone a scholar of Aurangzeb, remarks that “Aurangzeb built far more temples than he destroyed,” without having done any research on the subject. Aurangzeb, who once said “In the religion of the Mussalmans, it is improper even to look at a temple,”[2]must have rolled over in his spartan grave in the Deccan. Rudolph’s casual remark is incorporated uncritically into a footnote in Metcalf’s 1995 paper. A generation of South Asia scholars then cites Metcalf’s paper to assert confidently that Aurangzeb built far more temples than he destroyed, promoting this hoax in books (Copland 2013), papers (Brown 2007), and of course the Wikipedia article on Aurangzeb(!). At some point, Truschke must have come across Lloyd Rudolph’s hoax, and she recycled it without attribution, replacing “built” with “protected” to make it slightly less ridiculous.

Claim:

“Richard Eaton, the leading authority on temple destructions in India, puts the number of confirmed temple destructions during Aurangzeb’s rule at just over a dozen, with fewer tied to the emperor’s direct commands” (Truschke 2017, p.83-84).

This claim promotes another ubiquitous hoax. Eaton’s paper (Eaton 2000) lists 80 “instances” of temple desecration by Muslims between 1192 A.D. and 1760 A.D., and attributes roughly fifteen of them to Aurangzeb, which is how Truschke gets “just over a dozen.” However, Eaton does not define what he means by an “instance” of temple desecration, leaving it ambiguous[3]. The natural interpretation, made in numerous publications, is that it refers to the desecration of a single temple, as in the quote below from the textbook by Harbans Mukhia, the eminent JNU historian and authority on Mughals.

“…as recently recorded in Richard Eaton’s careful tabulation, some 80 temples were demolished between 1192 and 1760 (15 in Aurangzeb’s reign) and he compares this figure with the claim of 60,000 demolitions, advanced rather nonchalantly by “Hindu nationalist” propagandists.” (Mukhia 2008).

If we study the citations in Eaton’s list though, we see that this nonchalant equation of “instance” of temple destruction to the destruction of a single temple is blatantly wrong. For example, “instance 6” in the list is the attack on Benaras by Ghori’s army in 1194 A.D., and the citation Eaton gives says “nearly one thousand temples” were destroyed there. Even if this is an exaggeration, it is safe to assume that Ghori’s army did not go all the way to Benaras to conduct a surgical strike on exactly one temple before moving on. Turning to the Aurangzeb “instances,” we see that “instance 73” refers to Udaipur, where 172 temples were destroyed in 1680 A.D. according to the citation (Maasir-i-Alamgiri, abbreviated here on as M.A.), and “instance 74” refers to Chittor, where 63 temples were destroyed in 1680 A.D. according to the citation (M.A.). Even if we reduce the total number of temples destroyed in fifteen or so Aurangzeb “instances” by a half or a quarter, we are still well above “just over a dozen” temples.

Variations of Mukhia’s false claim about Eaton’s list are ubiquitous particularly in the mass media even in interviews of Richard Eaton. For example, the Indian journalist Ajaz Ashraf writes[4],

“Hindutva ideologues claim that 60,000 temples were demolished under Muslim rule. The professor of history explains how he came up with a figure of 80.”

Truschke promotes this hoax about Eaton’s list by referring to just over a dozen “temple destructions,” leaving the false impression that Eaton has shown that just over a dozen temples were destroyed under Aurangzeb.

A further problem with Eaton’s paper is that he does not give any objective criteria for selecting the “instances” on his list, so it is unclear why he left out many other temple destructions in the historical record (see, for example, the long list in Sarkar’s biography of Aurangzeb (Sarkar 1928, p.280-286)). Aurangzeb famously issued two orders for the destruction of the Somnath temple, one in the mid-1600s and another in 1706 A.D., as this letter of Aurangzeb’s attests, but neither is on Eaton’s list.

”The temple of Somnath was demolished early in my reign and idol worship (there) put down. It is not known what the state of things there is at present. If the idolators have again taken to the worship of images at the place, then destroy the temple in such a way that no trace of the building may be left, and also expel them (the worshippers) from the place.” [5]

Also missing from Eaton’s list is the destruction of the Kalka temple near Delhi in 1667. A Qazi informs Aurangzeb that Hindus are “gathering there in large numbers” to worship, so Aurangzeb orders the destruction of that temple and other temples nearby.[6] The Somnath and Kalka temples were located within Mughal territory and there is no record of their being associated with rebellions, so their destructions are counterexamples to the canonical narrative that temples were destroyed only if they were in territories under attack by Muslims or were associated with rebellions within Muslim domains.

Claim:

The Maasir-i-Alamgiri says that temple destructions under Aurangzeb were “relatively infrequent,” “unexpected,” and “unusual.” (abstracted from (Truschke 2017, p.84)).

The context of this claim is the following.

“A few beams of suggestive light shine through, however, that suggest temple destructions were relatively infrequent in Aurangzeb’s India. For example, the Maasir-i-Alamgiri of Saqi Mustaid Khan, a Persian language chronicle written shortly after Aurangzeb’s death, characterized the 1670 destruction of Mathura’s Keshava Deva temple as “a rare and impossible event that came into being seemingly from nowhere.” … The Maasir-i-Alamgiri has a noted tendency to exaggerate the number of temples demolished by Aurangzeb, which adds credence to its acknowledgement here that such events were unusual and unexpected.” (Truschke, p. 84).

When beams of suggestive light suggest something to Truschke, you can be sure that what is suggested is completely unsupported by the facts. It would be remarkable if the M.A. acknowledged that temple destructions under Aurangzeb were rare and unusual since chronicles of Muslim rulers invariably recount with great relish the destruction of large numbers of temples by the armies of the faithful. In fact, the M.A. is no exception and Truschke’s entire claim teeters perilously on the dodgy translation of a single word. Here is how the M.A. describes the destruction of the massive Mathura temple on pages 95-96.

Alhamdulillah (Praise be to god) ‘ala (upon) deen–i Islam (religion of Islam) kah (that) dar (in) ahd (reign) meimenet (blessed) mahd (cradle) khaneh barandaz (house wrecker) shirk wa toghian (idolatry and rebellion) chunin (such) amr (work/task) shegarf (wondrous) mumtana ‘al-wuqu’ (impossible event) az makman-i ‘adam (from the hiding place of nonexistence) ba ‘arsa-i zahur (to the realm of manifestation) amad (emerged).

Jadunath Sarkar simplifies the flowery Mughal Persian as follows.

“Praised be the august God of the faith of Islam, that in the auspicious reign of this destroyer of infidelity and turbulence [Aurangzeb], such a wonderful and seemingly impossible work was successfully accomplished” (Sarkar 1947, p.60).

Clearly, the M.A. is describing the destruction of the massive Mathura temple as a wonderful (shegarf) and impossible task that was nevertheless accomplished thanks to Allah and Aurangzeb[7]. Truschke translates “shegarf” as “rare” and misinterprets it[8] as “infrequent.” Amusingly, even Microsoft Bing translates “amr shegarf mumtana ‘al-wuqu” as “awesome thing,” capturing the meaning of the Persian phrase more accurately than Truschke’s mistranslation. The M.A. goes on to say this about the destruction of the Mathura temple.

“On seeing this instance of the strength of the Emperor’s faith and the grandeur of his devotion to God, the proud Rajas were stifled, and in amazement they stood like facing the wall. The idols, large and small, set with costly jewels, which had been set up in the temple, were brought to Agra, and buried under the steps of the mosque of the Begam Sahib, in order to be continually trodden upon. The name of Mathura was changed to Islamabad” (Sarkar 1947, p.60).

In short, the M.A. describes the destruction of the Mathura temple as a wonderful and difficult accomplishment, and says that the Hindu rajahs were humiliated, the idols of the Hindu gods were buried under the steps of a mosque for Muslims to step on, and a grand mosque was built at great expense over the ruins of the great Mathura temple. Truschke gives you a mistranslation of a small fragment of this passage, and assures you that the passage suggests temple destructions under Aurangzeb were “rare” and “unusual.”

If there is any residual doubt about the veracity of Truschke’s claim, consider how the M.A.’s concluding chapter summarizes Aurangzeb’s career accomplishments in temple destruction[9].

“Large numbers of the places of worship of the infidels and great temples of these wicked people have been thrown down and desolated. Men who can see only the outside of things are filled with wonder at the successful accomplishment of such a seemingly difficult task and on the sites of the temples, lofty mosques have been built” (Sarkar 1947, p.314-315).

Contrary to what Truschke would have you believe, there are no “beams of suggestive light” emanating from the M.A. that suggest that “temple destructions were relatively infrequent in Aurangzeb’s India.”

Claim:

“Aurangzeb and his officers understood that temple destruction was an extreme measure and so used it sparingly” (Truschke 2017, p.88).

The only evidence provided is the following.

“With only a handful of exceptions, Aurangzeb did not destroy temples in the Deccan…There were plentiful temples to be demolished in central and south India..but Aurangzeb did not consider temple demolition consistent with successfully incorporating new areas within the Mughal Empire…This approach suggests, among other things, that Aurangzeb and his officers understood that temple destruction was an extreme measure and so used it sparingly” (Truschke 2017, p.88).

The word “suggests” shows up again to do the necessary heavy lifting, and what is suggested shows Truschke’s confirmation bias, which is the refusal to acknowledge alternative explanations of events.

In this case, a more plausible explanation is given by the late Satish Chandra, JNU professor and eminent historian of the Mughal period. Chandra writes that in the Deccan, Aurangzeb had started by appointing “hatchet-men to dig up the foundations and destroy the stone temples in Maharashtra” (the original order says “to destroy and raze the temples of the infidels that meet the eye on the way” (Sarkar 1928, p.286)). However, by attacking the Bijapur and Golconda sultanates as well as the Marathas, Aurangzeb infuriated both Muslims and Hindus. After Bijapur and Golconda were subdued, Muslims in their armies even joined the Marathas in fighting the Mughal forces. Bogged down in the Deccan and with the entire countryside in revolt, Aurangzeb could not afford to further enrage Hindus, so he cut back on his program of temple destruction.

“Aurangzeb decided to deal with the growing disaffection by cancelling his decision to return to north India after 1689, and increased efforts to win over the Maratha sardars and Hindu zamindars and nayaks. To this end, he softened his policy towards Hindu temples. Unlike Marwar where limited resistance had led to a large number of old-standing temples being destroyed or shut down as if it was a dar-ul-harb, no such action was taken against Pidia Nayak who had actively aided Golkonda in resisting the Mughals. Nor was such action taken in the territories of other rebel zamindars in the Deccan” (S. Chandra 1986, p.380).

As for Aurangzeb considering temple destruction to be “an extreme measure” to be used “sparingly,” consider that he ordered the destruction of the Somnath temple in 1706 because “the idolaters have again taken to the worship of images”, as noted above. Even in the Deccan, Aurangzeb destroyed the temple of Vidhoba at Pandharpur, which is one of the most important Vaishnavite temples, and slaughtered cows there in 1705 A.D., just two years before he died. The reason? He was camped at Pandharpur, and he was furious when told that his Hindu soldiers were taking advantage of the opportunity to visit the temple and worship there.

“Aurangzeb halted at Pandharpur. That night Khwaja Mohammed Shah Mohtasib reported that there is a temple at Pandharpur and Hindus from the army are crowding and worshipping idols there. The emperor ordered that the temple be demolished. and butchers from the army should go to the temple site and slaughter cows. Muhammad Ishaq son of Tarbiyat Khan Bahadur should disperse the crowds. The emperor’s orders were duly carried out.”[10]

Even towards the end of his life, Aurangzeb destroyed major temples at Somnath and Pandharpur because Hindus were “worshipping idols there,” as his own court documents say, contradicting Truschke’s fictitious claim that “Aurangzeb and his officers understood that temple destruction was an extreme measure and so used it sparingly.”

Patronization of Hindu and Jain Temples

Claim:

“… Aurangzeb granted land at Shatrunjaya, Girnar, and Mount Abu – all Jain pilgrimage destinations in Gujarat – to specific Jain communities in the late 1650’s” (Truschke 2017, p.81).

As per the farman, the grant had little to do with Jainism, and was actually a reward to Shantidas Jhaveri (also known as Satidas Jawahari), a powerful and well-connected Gujarati Jain jeweler and financier, for coming to Aurangzeb’s aid at a critical time during the war of succession between Aurangzeb and his brothers. Note that the farman was issued in 1660 A.D., a few months after Aurangzeb won that war.

“At this time the exalted Farman is issued that since Satidas Jawahari, son of Sahasbhai, of the Srawak community, has solicited and been hopeful for special favours, and has greatly helped the army during its march with provisions, and expects to be honoured with special rewards, therefore the village (deh) of Palitana, which is under the jurisdiction of Ahmadabad, and the hill of Palitana famous as Satrunja, and the temple on it, all these we give to the said Satidas Jawahari of the Srawak community. Further that the grass which grows there may be used for grazing by the animals and cattle of the Srawak community; and the timber and fuel which is to be found on the hill of Satrunja should belong to the Srawak community so that they may utilize these for whatever purpose they like…..Besides this, there is a mountain in Junagadh famous as Girnal (Girnar) and there is another hill at Abuji under the jurisdiction of Sirohi. We give these two hills also to Satidas Jawahari of the Srawak community as a special favour so that he may be entirely satisfied.” (Commissariat 1987, p.74-75)

Aurangzeb gave this grant to close the books on the debt he incurred to Jhaveri during the war of succession (“so that he may be entirely satisfied“), and not because he was a crypto-Jain or admired Jainism. In fact, in 1645 A.D., Aurangzeb, then the Governor of Gujarat, desecrated and destroyed the same Shantilal Jhaveri’s magnificent Chintamani Parshvanath Jain temple, which was described by the German traveler Mandelslo as “without dispute one of the noblest structures that could be seen“. The French traveler Jean de Thévenot writes that Aurangzeb desecrated the idols, slaughtered a cow in the temple, and converted the temple into the Quvvat-ul-Islam (“Might of Islam”) mosque. Jhaveri, a trusted jeweler to both Jahangir and Shah Jahan, probably complained to Shah Jahan, who issued a farman in 1648 A.D. restoring part of the premises to Jhaveri. The Jain community had spirited away the main idols before the desecration and installed them in other temples, so they did not restore the temple and it disappeared from the pages of history. (Commissariat 1995, p.101-102)

Truschke’s laconic description of the desecration and destruction of this magnificent Jain temple is:

“..he [Aurangzeb] ordered mihrabs (prayer niches, typically located in mosques) erected in Ahmedabad’s Chintamani Parshvanath temple” (page 84)

She casually skims over it as if this were an interior decoration project that didn’t quite pan out. It is perhaps superfluous to add that Aurangzeb’s desecration of this temple is not on Eaton’s list.

Claim:

“In 1691 Aurangzeb conferred eight villages and a sizeable chunk of tax-free land on Mahant Balak Das Nirvani of Chitrakoot to support the Balaji temple” (Truschke 2017, p.81).

According to the local legend[11] (Pachauri 2013), Aurangzeb and his army were at Chitrakoot in June 1691 A.D. during a campaign of temple destruction when they fell ill with unbearable pain in their stomachs. Even the court physicians were helpless to cure them. In desperation, the emperor appealed to a local priest, Mahant Balak Dasji of the Balaji temple, who saved everyone with an herbal potion. A chastened Aurangzeb promised not to destroy any more temples in that region and issued a farman conferring 330 bighas of fertile land with eight villages and one rupee daily from the state treasury for “meeting the expenses of puja and bhog” of the idol of Thakur Balaji.

On the day of this miracle, Aurangzeb was 1300 km away in Bijapur fighting the Marathas,[12] and there is no record of his ever having visited Chitrakoot. Perhaps that is part of the miracle.

Nevertheless, the Chitrakoot temple claims to have the farman, and it was examined a few years ago by the journalist Pankaj Pachauri (Pachauri 2013). Pachauri noted many anomalies in the farman:

- The farman begins with the incantation “Allah-ho-Akbar”[13] but Aurangzeb’s farmans always began with “Bismillah-hir-Rehman-nir-Raheem” (Moin 2022). Pachauri writes that someone has pasted a piece of paper with “Bismillah..” over the “Allah-ho-Akbar” incantation as part of a “restoration.”

- The zimn (the back of the farman), traditionally written after the main text, has a date preceding the date in the main text.

- There are numerous grammatical mistakes in the text of the farman.

- The farman is a grant directly from Aurangzeb even though there is no record of any connection between him and the Balaji temple, which is an insignificant temple even within Chitrakoot.

Pachauri writes that Irfan Habib examined the farman and pronounced it authentic, brushing aside these problems and “restorations.” Given Habib’s record of obfuscation in the matter of the provenance of the Vishnu Hari inscription found at the Babri Masjid[14], the farman needs to be examined by more credible experts. It may be a forgery, although if it is, one must admire the sense of humor of the forger who made “Abraham in India’s idol house” give a grant not just for the maintenance of the temple but for “meeting the expenses of puja and bhog” of an idol worshipped by Hindus.

Claim:

Aurangzeb (i) directed Bhagwant Gosain in Benaras to be kept free of harassment and gave empty land in Benaras to Ramjivan Gosain, (ii) gave grants to the Umanand temple in Gauhati, (iii) gave the Jain monk Lal Vijay Gani a monastery, and granted tax relief for many Jain upasrayas, and (iv) gave land to a Brahmin named Rang Bhatt in eastern Khandesh. The list goes on (abstracted from (Truschke 2017, p.81-82)).

The book has a longer list but studying the citations reveals an amazing fact: almost all the evidence for these grants comes from a single mysterious figure[15] in the distant past whose publications identify him only as “Jnan Chandra, Bombay” with no affiliation to a university or research institution. In October 1957, Jnan Chandra and the Russian satellite Sputnik emerged from the hiding place of nonexistence to the realm of manifestation, as the M.A. might say, although in his case, it was with a paper titled “Aurangzib and Hindu temples” (J. Chandra 1957) in the Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society (JPHS) rather than Sputnik’s beeps at 20 MHz. In the next year and half, Jnan Chandra wrote a paper every two months in JPHS, before disappearing into the hiding place of nonexistence in April 1959, a few months after Sputnik. Harbans Mukhia refers enthusiastically to “the Bombay scholar Jnan Chandra’s celebrated articles in Pakistan Historical Society Journal [sic],” (Mukhia 2008) but he accepts in email exchanges that he does not know anything else about the Bombay scholar. Asked about Jnan Chandra, Truschke responds, “Jnan Chandra was a well-respected scholar.”

She has no clue either.

Whoever he was, the well-respected Bombay scholar writes in his first celebrated paper (J. Chandra 1957) that in the course of his studies, he had “come across more than two dozen documents that were never seen by the historians who worked on the subject [of Aurangzeb’s solicitude for non-Muslims].” He published six more papers on his findings[16], and even a cursory examination of these papers raises a host of red flags. This is not the place for a full discussion, but salient points are summarized below.

First, the papers are filled with spelling mistakes (“deciple” instead of disciple, “monestry” instead of monastery, etc.) and grammatical mistakes (“..in a very laudable terms,” “..had an equal respects for other religions,” “His this attitude of tolerance and respect..”). Some of these might be typos, but the difficulty with articles and the unusual phrase “His this..,” which occurs in several places, and was obviously constructed by translating each word in the Hindustani phrase “Unka ye..”; show that the celebrated Bombay scholar was probably a Hindustani speaker with a limited command of English and without the resources to get his manuscripts corrected before publication.

Also striking is his deep sense of grievance at how badly Aurangzeb has been treated by historians on account of Hindus. If Aurangzeb’s farmans always start with Bismillah, his devotee’s papers always start with a bitter complaint like:

“Aurangzib is the most maligned personage of Indian history…” (J. Chandra 1958(a))

Elsewhere he grouses poetically,

“It is a pity that biased historians – who have left not a single stone unturned to prove Alamgir to be anti-Hindu – have ignored even the oft-quoted contemporary evidence whenever it did not suite [sic] their sweet will.” (J. Chandra 1958(b)).

The prose is fractured but resentment bubbles through it like lava.

Of course, even resentful Aurangzeb fanboys with bad English can have interesting things to say, but digging through Jnan Chandra’s claims turns up even more red flags. Although he seems to have been an amateur scholar with limited means, powerful people from all over the subcontinent shower him with copies of farmans and parwanas. The provenance of these documents is described in vague terms, and only the English translation is provided in some cases while in other cases, the alleged Persian text is transcribed as well, but it is impossible to tell whether these farmans actually exist.

- The two farmans in favor of Bhagwant Gosain and Ramjivan Gosain (J. Chandra 1957) were “brought .. to my [Chandra’s] knowledge” by S.M. Jaffar, who turns out to be a distinguished Pakistani historian and the first director of Pakistan’s archives (Jaffar 1961). Only the English translation is given. Jnan Chandra’s paper does not explain why the preeminent Pakistani historian of his time, who lived and worked in Peshawar in Pakistan’s North-West Frontier Province, would send copies of farmans to an unknown amateur historian in Bombay or where one might find the original farmans today.

- An obscure Assamese journal is said to have reproduced the farman for the grant to the Umananda temple “for bhog of the idol” (presumably, the grant for “puja of the idol” was a different farman), and it was brought to the Bombay scholar’s attention by Vishnu Ram Medhi, Chief Minister of Assam, and later, Governor of Madras (J. Chandra 1957). Only the English translation is given.

Medhi is a forgotten figure today but in the late 50’s, he was famous as the “Iron Man of Assam” for ensuring that Assam became a part of India after Partition[17], and later, for cracking down hard on illegal immigration of Muslims from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). In fact, he was removed from his position as Chief Minister of Assam and exiled to Madras because he clashed with the Congress party’s Muslim leaders such as Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed on this issue.

There is no information about why a Chief Minister of Assam who was an organic chemist by training and a die-hard opponent of Pakistan, Islamic rule, and Muslim migration, would send an unknown amateur historian in Bombay a copy of a farman that appeared in some obscure journal and showed Aurangzeb in a positive light. It is unknown where the original farman can be found today. - The only proof provided that Aurangzeb gave a monastery to Jain monk Lal Vijay Gani and provided relief for Jain upasrayas is that poems written by Jain monks claim that the farmans exist. (J. Chandra 1958(a))

- A farman for the grant to Rang Bhatt in Khandesh was discussed in a Lahore magazine called “Lajawab”, and Jnana Chandra translated it into English (J. Chandra 1959). There is no other information about the actual farman. An article in the Pakistani newspaper Dawn (Parekh 2019) says that a magazine called “Intekhab-i Lajawab” used to publish “interesting facts, figures, jokes and informative pieces.” It is unclear whether this is the same magazine, and if so, whether the alleged farman was published in the jokes section or in the informative pieces section.

One has to have a heart of stone not to burst out laughing at the tale of the amateur Bombay scholar with modest means and bad English who was nevertheless a close friend of powerful people all over the subcontinent and was showered with farmans while sitting in his house in Bombay.

Of the eight “patronage farmans” discussed here, only the Shantidas Jhaveri farman rings true, and it was a repayment of a debt to a powerful financier rather than patronage of Jainism. An in-depth, honest study of the Chitrakoot farman, the celebrated Bombay scholar’s farmans, and others, is required to establish the truth about the “puja and bhog” farmans.

It is also worth noting that many of these alleged “puja and bhog” grants involve trifling sums of money. One of Jnana Chandra’s papers (J. Chandra 1958(c)) discusses two parwanas in which local Mughal officials grant Rs. 10.50 annually to a priest named Kanji Brahman at the Mahakaleshwar temple in Ujjain. To put this in perspective, the French traveler Bernier writes that to bathe in the Yamuna during a solar eclipse, Hindus had to first pay Aurangzeb “a lecque of roupies, equal to about fifty thousand crowns” (Bernier 1916). Jnana Chandra recounts Bernier’s tale in one of his papers (J. Chandra 1958(b)) although in his telling, the immense sum Hindus had to pay to bathe in their own river is not mentioned and instead, they bring “presents” for their beloved emperor. The well-regarded Bombay scholar may have been an amateur historian, but he promoted his idol by shading the truth as slickly as any contemporary South Asia scholar.

Conclusion

The received historiography on Aurangzeb is riddled with outlandish hoaxes that have gone unchallenged for decades. Truschke’s book is a worthy addition to this genre since it refreshes our memories of these hoaxes while enthusiastically manufacturing new ones.

For a hoax to be long-lived, it is important to preemptively cast doubt on sources of information that might contradict the hoax. Not surprisingly, Truschke ends her book by warning her readers that they will get confused if they read history books on their own, so they should leave it to her and her coterie of South Asia scholars to interpret history for everyone else. Muslim chroniclers such as Saqi Mustad Khan (the author of the Maasir-i-Alamgiri) “did not obsess about getting the facts right,” and they exaggerated the scale of slaughter, slavery, and temple destruction to please their Muslim patrons. English translators of these chronicles “selectively translated” the most horrifying passages in these books to sow division between Hindus and Muslims as part of the divide-and-rule policy of the Empire. Hindu historians such as Jadunath Sarkar were communal and Sarkar’s analysis “lacked historical rigour.”

These criticisms would be more credible if they did not come at the end of a book that tells you that beams of suggestive light emanate from the Maasir-i-Alamgiri suggesting that temple destructions under Aurangzeb were rare and unusual, and in which the most fantastic farmans from the famous Bombay scholar Jnana Chandra are quoted without a hint of scepticism (“I especially rely on Jnan Chandra’s articles on Aurangzeb’s farmans concerning Hindu temples and religious communities” (Truschke 2017, p.133)).

In a healthy academic discipline, there are vigourous debates between researchers with divergent viewpoints, and these disagreements help to eliminate error and firm up the foundations of the field. Einstein famously did not believe in quantum mechanics[18] but given his reputation, Bohr, Schrodinger, and other physicists invested considerable effort to address his objections. Today, no mainstream physicist believes that Einstein was right, but everyone acknowledges that his attacks on quantum mechanics played a critical role in firming up the philosophical foundations of quantum mechanics.

In South Asia studies, there are certainly people such as Koenraad Elst and Meenakshi Jain who have challenged the dominant narrative. Some years back, Elst debunked the asinine hoax promoted assiduously for years by historians such as B. N. Pande and Gargi Chakravartty that Aurangzeb destroyed the Kashi Vishwanath temple because the Maharani of Kutch was raped in the sanctum by evil Brahmins (Elst 2002). Unfortunately, dissenters are invariably excommunicated and cast out into the hiding place of nonexistence by the high priests in the church of South Asia Studies in India and the West. This has resulted in a sterile monoculture in which even the most foolish hoaxes like “Aurangzeb built far more temples than he destroyed,” and “Eaton, the world’s expert on temple destruction, has proved that Muslims destroyed only 80 temples between 1192 A.D. and 1760 A.D.,” have spread like manure, unchecked by what scientists call a “bullshit filter.”

In as much as Jadunath Sarkar was a man of his times, Audrey Truschke is a woman of our times. Truschke’s book should have been called “Aurangzeb for Dummies.”

___________________

Works Cited:

Bernier, Francois. 1916. Travels in the Mogul Empire A.D. 1656-1668. London: Oxford University Press.

Brown, Kathleen Butler. 2007. “Did Aurangzeb Ban Music? Questions for the Histiriography of His Reign.” Modern Asian Studies 77-120.

Chandra, Jnan. 1959. “Alamgir’s Grant to a Brahmin.” Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society.

Chandra, Jnan. 1958(c). “Alamgir’s Grants to Hindu Pujaris.” Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society.

Chandra, Jnan. 1958(a). “Alamgir’s Tolerance in the Light of Contemporary Jain Literature.” Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society.

Chandra, Jnan. 1957. “Aurangzib and Hindu Temples.” Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society.

Chandra, Jnan. 1958(b). “Freedom of Worship for the Hindus Under Alamgir.” Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society.

Chandra, Satish. 1986. “Some Considerations on the Religious Policy of Aurangzeb During the Later Part of His Reign.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Volume I. 369-381.

Commissariat, M.S. 1987. “Discovery of New Farmans on Shantidas: Financial Loans Made by His Family.” In Studies in the history of Gujarat, 74-75. Ahmedabad: Saraswati Pustak Bhandar.

—. 1996. Mandelslo’s Travels in Western India. Asian Educational Services.

Copland, Ian, et al. 2013. A History of State and Religion in India. Routledge.

Eaton, Richard. 2000. “Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States.” Journal of Islamic Studies 283-319.

Elliot, H. and Dowson, J. 1877. The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. London: Trubner Company.

Elst, Koenraad. 2002. “Why did Aurangzeb Demolish the Kashi Vishwanath?” In Ayodhya: the case against the temple, by Koenraad Elst. Delhi: Voice of India.

Jaffar, S.M. 1961. History of Histories. Peshawar: Gandhara Hindko Academy.

Jain, Meenakshi. 2020. The Battle for Rama: Case of the Temple at Ayodhya. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

Jalaluddin. 1978. “Some Farmans and Sanads of Medieval Period of U.P.” Studies in Islam 44-45.

Khan, Saqi Musta’idd. 1985. The Maasir-i Alamgiri. Osnabruck: Biblio Verlag.

Metcalf, Barbara. 1995. “Too Little and Too Much: Reflections on Muslims in the History of India.” The Journal of Asian Studies 951-967.

Moin, A. Azfar. 2022. “Sulh-i kull as an Oath of Peace: Mughal Political Theology in History, Theory, and Comparison.” Modern Asian Studies 721-748.

Mukhia, Harbans. 2008. The Mughals of India. Cambridge University Press.

Pachauri, Pankaj. 2013. “Chitrakoot: A Temple with a Proud Muslim Legacy.” India Today, December 19: https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/religion/story/19870915-chitrakoot-a-temple-with-a-proud-muslim-legacy-799254-1987-09-14.

Parekh, Rauf. 2019. Literary Notes: Munshi Mahboob Alam and Paisa Akhbar. https://www.dawn.com/news/1483379.

Qasmi, Mufti Akhtar Imam Adil. 2014. Islamic Law: The Distinguishing Features as Compared with the Un-Islamic Legal Systems of the World. Mufti Zafiruddin Academy.

Rather, Aqib Yousef. 2022. “A Note on Conception of Aurangzeb Alamgir Religious Policy.” Journal of Psychology and Political Science 15-22.

Sarkar, Jadunath. 1928b. History of Aurangzib Volume V, p4. Calcutta: M.C.Sarkar and Sons.

—. 1928. History of Aurangzib, Vol. III. Calcutta: M.C.Sarkar and Sons.

—. 1947. Ma’asir-i Alamgiri. Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal.

Truschke, Audrey. 2017. Aurangzeb: The Life and Legacy of India’s Most Controversial King. Stanford University Press.

[1] https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/genocide-of-european-roma-gypsies-1939-1945

[2] Umurat-i-Hazur Kishwar-Kashai Julus, 13th October, 1666

[3] Koenraad Elst was one of the first to point out this problem (Elst 2002).

[4] https://scroll.in/article/769463/

[5] Inayetullah’s Ahkam, 10a; Mirat 372. Translation in (Sarkar 1928, p.320).

[6] Siyah Akhbarat-i-Darbar-i-Mu‘alla, Julus 10, Rabi II, 3/12 September 1667.

[7] The previous sentence says, “In a short time by the great exertions of his [Aurangzeb’s] officers, the destruction of this strong foundation of infidelity was accomplished, and on its site a lofty mosque was built at the expenditure of a large sum.”

[8] The standard Hayyim and Glosbe dictionaries translate shegarf as “wondrous,” “wonderful,” and “amazing.” Only Steingass gives “rare” as a translation but follows it with “fine,” “excellent,” “great,” and “glorious,” so it is clear that “rare” here means “fine” or “glorious” rather than “infrequent.”

[9] As mentioned before, a long list of Aurangzeb’s temple destructions, many of them taken from the M.A., can be found in Sarkar’s biography of Aurangzeb (Sarkar 1928, p.280-286).

[10] Akhbarat 49-7. Translation in (Sarkar 1928, p.286).

[11] The current priest of the temple recounts the legend in this video: https://youtu.be/CgH5HNJZa6A

[12] Aurangzeb was in Bijapur between March 1691 A.D. and May 1692 A.D. (Sarkar 1928b, p.4).

[13] This can be seen in Jalaluddin’s paper, which gives the text of the farman (Jalaluddin 1978).

[14] See Chapter 10 of Meenakshi Jain’s book (Jain 2020).

[15] “I especially rely on Jnan Chandra’s articles on Aurangzeb’s farmans concerning Hindu temples and religious communities” (Truschke 2017, p.133).

[16] These papers are available on ProQuest.

[17] https://amritmahotsav.nic.in/unsung-heroes-detail.htm?466

Leave a Reply