"For a long time, Marxist historians had a hegemonic hold on only one type of discourse. Marxist linear history represents India and its traditions as the past, or decadence, and the West as the future, or progress. In a world where globalisation, trade, and mutual exchange are a given, it is disagreeable to argue that perhaps we needed an invasion or colonisation to open our eyes to the world."

Understanding Indian Economy: Ancient To Modern – Part 1

Introduction

It is frustrating for a layperson to understand the economic history of India when the same set of facts gets opposite ‘expert’ interpretations. Was and is India rich or poor? If we were so poor, why did the whole world come to plunder us when we should be doing so in reverse? If we are a poor country, why does the world still come to us? For a long time, Marxist historians had a hegemonic hold on only one type of discourse. Marxist linear history represents India and its traditions as the past, or decadence, and the West as the future, or progress. Without denying the patriotism of the Marxist scholars or the politicians using their ideas in formulating our economic policies, we have almost fossilised our self-understanding as that of a permanently poor country for ages.

The GDP (gross domestic product) of India was always high. However, the GDP per capita, that is, the GDP divided by the population of India, was never so high. The high population in the denominator always seems to be a factor pulling the numbers down. Is a high population good or bad? Despite all the disputes, the Indian economy stood on strong ground, with a mix of the bad and ugly too, across the centuries. We now stand among the top five economies in the world. Left alone, we might have evolved in a better manner. The invasions and colonisations may have had their proponents and apologists, but they were clearly disruptive. One does not seek reasons for history because it is an exercise in futility. However, in a world where globalisation, trade, and mutual exchange are a given, it is disagreeable to argue that perhaps we needed an invasion or colonisation to open our eyes to the world.

The following sections are a compilation of many sources to understand the entire Indian economic story without making any claims of primary scholarship. The idea is to understand, as an ordinary citizen of Bharat, the depictions of our economic history. Disturbingly, most of our histories are Delhi-centric. Regional economic histories of the North-East, Marathas, and South (especially the rich maritime trade) remain largely neglected. The recent past has seen a sustained effort towards regional history. As one scholar says, this deliberate positing of regional history will extricate us from an empire-centered view of history, which continued even after independence, in which the Mauryan, Mughal, and colonial British Empires formed a norm of continuum.

Economic History of India- Complex and Controversial Trends in Depiction

The economic history writing in India originated in the controversial assessment of British rule on the Indian economy, says Mamta Dwivedi in her wonderful paper, Trends in Economic History Writing of Early South Asia. Historiography has been through several dominant schools of history writing: colonial, nationalist, Marxist, post-structural, postcolonial, and so on. These were neither successive nor mutually exclusive, with overlaps in methods, theories, and research interests.

As Dwivedi writes, colonial writings, like those of James Mill and Max Mueller, rejected the unhistorical and mythological Indian texts with incoherent periods in terms of millions of years. The firm fixing of periods was mainly after the clear establishment of the ‘Buddhist period’ (using Pali literature and inscriptions at temples and monasteries). Roman and Greek writings on Alexander also helped. James Mill distinguished three periods: Hindu, Muslim, and British, which gradually became the ancient, mediaeval, and modern periods, respectively.

Karl Marx took this forward without ever visiting India or studying India the way he studied other colonised countries. For him, India was a classic example of an “Asiatic mode of production”. This was the absence of private ownership of land; the predominance of a village economy with occasional towns functioning more as military camps or administrative centres than commercial hubs; self-sufficient and closed village economies meeting their own agricultural needs and manufacturing essential goods; a lack of surplus for exchange fostered by the state that collected large shares of the surplus used by a despotic ruler for his luxurious life; complete subjugation of rural communities; and control over the irrigation works by the state. This became a template for all future Marxist descriptions of India.

As Dwivedi explains in the article, the discoveries of the Indus Valley Civilization and Kautilya’s Arthashastra in the early 20th century challenged these ideas radically. Indian civilization was now at least 5000 years old, and ancient Indians’ capacity for rational thought put them on par with the Greek and Roman political and economic thinkers. Archaeological studies problematized the periodization of Indian history, clearly a gross injustice that the entire Indian history of thousands of years before Islam became a single package of ‘ancient’.

Arthashastra demolished the notion of an apolitical India of stagnation, lacking a sense of history, and ruled by a typical despotism of the Orient. An indigenous ‘nationalist’ school of history now tries to restore the great Indian past and its rich heritage through discussion on topics like agrarian structures, property ownership, urbanism, city planning, and long-distance trade.

Marxist history gained prominence in the 1940s, and more so after independence, where economic determinism became the underlying philosophy of critiquing the West along cultural, political, and economic lines. The period between 1950 and 1990, a phase of socialist leaning, had economists seeing great relevance in history.

The discipline of economics abandoned the paradigm of Marxist political economy in the phase after economic liberalization. Over the last decade, historiographical studies have seriously placed ideas in their historical contexts. These explore the encounters between Western rationalism and Indian philosophies. They illustrate how Western scholars struggled with the Indian concepts of time, history, chronology, and identities.

The different schools of history writing have different perspectives on various issues like the organisation of agricultural society, defining urban spaces and urbanisation, the development of states by economic activity, the relation of Buddhist monks and Indian Vysya guilds to developing trading connectivity, and the Indo-Roman trade (who benefitted? India, Rome, both, or none); and so on. Today, a major point of contention in the history of the economy is whether British rule was good or bad for India.

ECONOMY OF ANCIENT INDIA

This section is a summary of a brilliant six-part series (www.indictoday.com/long-reads/role-ancient-indian-economy) by Sneha Nagarkar. Vartta (livelihood) was a recognised branch of knowledge along with Anvisiki (philosophy), Trayi (Vedic knowledge), and Dandaniti (royal, just rule).

Vartta, composed of the three fundamental vocations of agriculture, trade, and animal husbandry, supported most ancient and mediaeval pre-industrial economies. Across centuries, Indic texts stressed Vartta as the prime duty of a king and made it obligatory upon him to provide his subjects with the same. In the four human purposes of human life, Dharma, Artha, Kama, and Moksha; Vartta was the means to artha (money) based on dharmic principles. Also, other purposes too remain difficult without artha. Vedas; Rama’s counsel to Bharata; Narada, Vidura, and Bhishma speaking at various times in Mahabharata; BhagvatPurana, and many major texts incorporated the importance of dharma in acquiring money. This knowledge, glorifying austerity but not poverty, ensured individual and group material prosperity.

Agriculture of Ancient India

Agriculture has been the most enduring foundation for the Indian economy. Mehrgarh (now Pakistan) shows the earliest evidence of agriculture, dating back 10,000 years. The Vedas considered agriculture a noble profession and described ploughs, ploughshares, ground furrows, canals, wells, water resources, and agricultural processes in clear detail. The Ramayana, Mahabharata, Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, Yajur Veda, and Taittiriya Samhita also provide clear descriptions of agricultural fields, processes, types of crops, and the seasons of harvest. Agriculture provided the backbone for urbanisation in the mature phase of the Sindhu-Saraswati civilization (2600–2000 BCE).

Buddhist texts of the 5th and 6th centuries BCE clearly depicted agricultural processes and the associated rituals. It shows a well-developed agrarian economy. Individuals could own land privately. A gama was a rural settlement; the arable lands were the khettas. These words carry the same meaning even today. Later, the Arthashastra of the Mauryan era gives a most detailed exposition on agrarian practices. Land acquisition, the ownership rights, the king’s rights, the different types of grains, irrigation facilities, the provision of loans for cattle and grains, agricultural implements, seasonal harvesting, the tax structure, provisions during famines, and many more issues regarding agrarian practices have a place in this text. Rice, wheat, barley, millets, pulses, and sugarcane were common agricultural products. Megasthenes, who visited Chandragupta Maurya’s court, praised the fertile fields of North India and the irrigation facilities provided by the government.

The Kusanas (1st century CE to 3rd century CE) and the Satvahanas (1st century BCE to 3rd century CE) after the Mauryan (322 BCE–185 BCE) period consolidated the agricultural practices. During the Satvahana period in the South, there were three kinds of ownership of agricultural lands: the state, landholders, and individual farmers. Ploughs, the use of oxen, irrigation facilities, and the use of manure helped agriculture grow. The Guptas and the Vakatakas followed the Kusanas and the Satvahanas, respectively. By the Gupta period, granaries were in existence for storage.

Varahamihira of the Gupta period, in his Bṛihat Saṃhita, gives predictions of rainfall through meteorological calculations. The Krishi Parasarah (4th century BCE to 4th century CE) covers all the aspects of agriculture, such as meteorological observations, field management, management of cattle, agricultural tools and implements, seed collection and preservation, ploughing, and all the agricultural processes involved, right from preparing fields to harvesting and storage of crops.

Trade and Finance of Ancient India- The Role of the Guilds

Ancient India had a vibrant and dynamic system of merchant groups or guilds controlling the manufacturing sector and the trade networks. Collective investments; group travelling for trade purposes; varna and jati groupings; securing identity with localised expertise in crafts; familial transmission of trade practices; urbanisation in the 6th to 7th centuries BCE in the Gangetic plains; and established trade routes were the various reasons that helped in the rise of guilds across the kingdoms. The Vedas and the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad have some references to guild organisations.

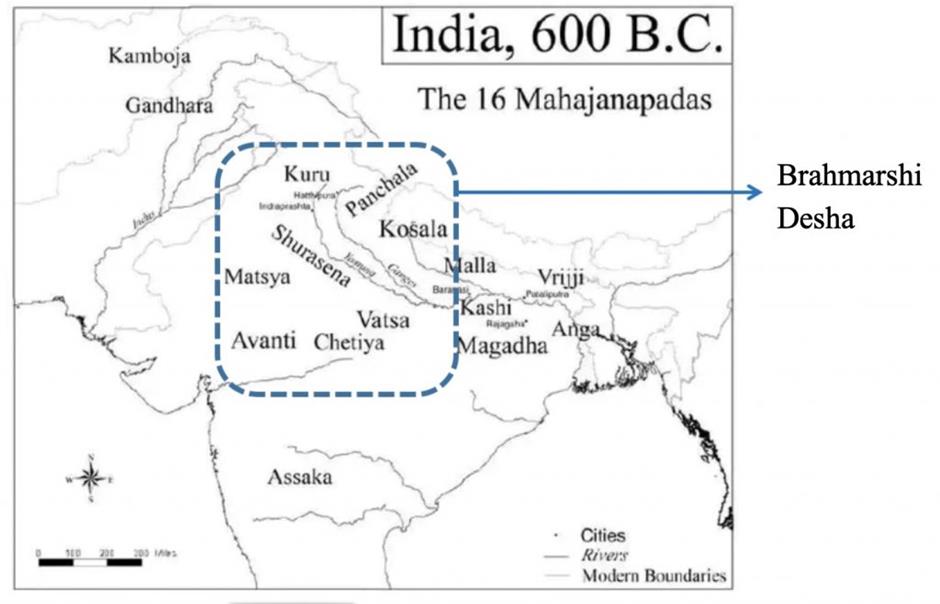

Since the 6th century BCE (the first urbanisation phase of the Gangetic Plains), there have been unprecedented economic, political, and religious transformations. Till 320 BCE, the sixteen independent kingdoms (Mahajanapadas) listed in Buddhist and Jaina literature greatly encouraged trade and commerce. The Gautama Dharmasutra (5th century BCE) has the first clear reference to guilds of farmers, merchants, cattle herders, moneylenders, and artisans that had legal power concerning members of their respective groups. The Jataka Tales mention eighteen different kinds of guilds, craft industries, and the principle of heredity in vocations.

200 BCE to 300 CE (the Sungas, Sakas, Kusanas, and Satvahanas) was a golden period of Indo-Roman trade, Buddhist encouragement of trade, and many types of guilds. Mahavastu, a Buddhist text, mentions twenty-four types of guilds, including those for oil pressers, potters, weavers, and bankers. The guilds gave donations, took interest in charitable works, functioned as banks giving interest on the deposited money, and issued their own coins, as evident in archaeological surveys.

Indian guilds were at the forefront of offering their service to the elite as well as the common people. The interest generated by the endowments raised many of the funds. Performing an immense variety of functions, the guilds constructed houses, temples, assembly halls, tanks, parks, and water reservoirs; performed Yajnas; provided food for the needy; helped society during distress and natural disasters; provided for defence expenditures; and allocated funds to the mentally and physically challenged, orphans, and destitute women.

The Buddhist guilds funded the construction of rock-cut dwellings, arable land, pillars, and water cisterns for monasteries. Many of these sites were on major trade routes, and some, like Mathura, were important trading places themselves.

The inscriptions, Panini’s Ashtadhyayi, Gautama Dharmasutra, and Arthashastra describe banking functions like money-lending, creditors, debtors, loans, interest, repayment, and surety, which indicates that around the 5th century BCE, money-lending had become a common function. The Arthashastra has mention of adesa, akin to the modern bill of exchange or a letter of credit.

The post-Mauryan (2nd century BCE to 3rd century CE) world saw an increase in the money economy, coins, and banking services as international trade increased. By the 1st century CE, the guilds were strong in the economic and political spheres, and common people, as well as high state officials, placed immense faith in them for their effectiveness and honesty. Senior royal officers used the interest received on money deposits for charitable work. Permanent endowments in the form of gold and silver to guilds continued in the Gupta period, as noted in inscriptions from near Prayag in Uttar Pradesh.

The Guptas period, prominent from 300 CE to 600 CE, showed a slackened Roman trade but a strengthening with Southeast Asian countries. The Jain and Buddhist texts, the Dharmashastras, art, and poetry of that period, like Kalidasa’s Raghuvamsha, give a description of the growth of guilds during this period. The banking functions of guilds increased, and there were guilds of goldsmiths and carpenters too. The guilds had influence over the king and were part of the jury while trying cases involving traders. However, from the 7th century onwards, in the post-Gupta period, guilds began to gradually decline in trading and economic power.

Indo-Roman Trade: The Golden Period of Indian Economy

Regarding the Indo-Roman trade, the dominant view is that the trade favoured India. An opposite view favours the Mediterranean, Egypt, and West Asia. The third view states difficulty in calculation in the absence of detailed statistics. Indo-Roman trade started in the 1st century BCE, matured in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, and declined in the 3rd and 4th centuries CE with the fall of Satvahanas and Kusanas in India and the Roman Empire itself in the 4th century CE.

The Sakas and Satvahanas in the north and south, respectively, controlled the sea trade. The Kusanas controlled the land trade and even had Roman gold coins issued to promote foreign trade. There was a Roman influence on Indian art and goods too. Sphinx sculptures in cave complexes, the carving of Bactrian camels, the design of Indian lamps in Roman style, and the issuance of coins with images of large ships are all examples of this influence.

Bharuch in today’s Gujarat, under the Ksatrapa rulers of Saurashtra, was the key port in this trade. The seaborne journey from Rome to the western coast of India took approximately sixteen weeks. Bharuch had trade relations with inland cities: ancient Pratisthana (modern Paithana) and Tagara (or Ter), both in Maharashtra; Masulipattanam and Vinukonda in Andhra Pradesh; and Kalyana near Mumbai.

From India, there was the export of circus animals, muslin, cotton, ivory, tortoise shells, herbs and spices, dyes like indigo, sesame oil, wood, wheat, ghee, fragrant ointments, and precious stones. Roman legislators lamented that the payment of Roman gold and silver to India strained their economy. Except for Chinese silk, India dispatched the rest of the Chinese exports to Rome. India imported wine along with copper, tin, lead, coral, topaz, and waist girdles.

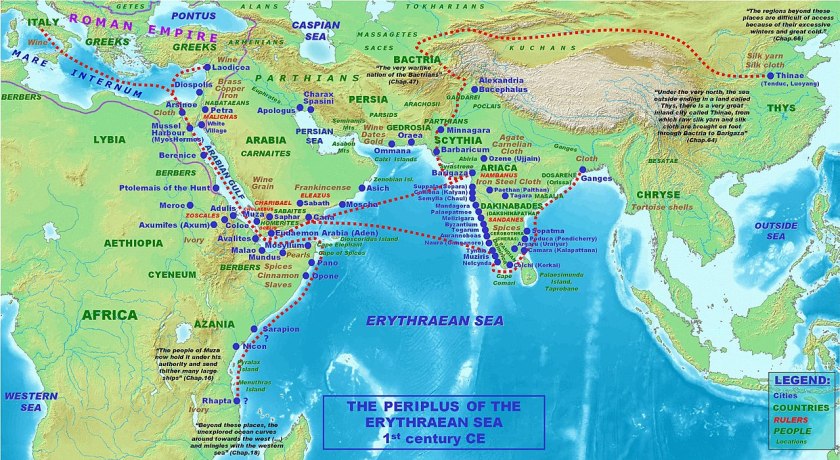

Periplus on the Erythraean Sea, a travelogue written by an unknown Greek sailor and merchant, is one of the major sources for reconstructing the history of this trade. The Periplus informs us about the important ports on the west coast of India, like Kalyana, Sopara (a Buddhist site), Sesecrienae (Aegedi, Goa), and the port of Muziris. The last, somewhere in Kerala, was an important port from where an inland trade route went through Palakkad and reached the East Coast.

The Pandya rulers of Madurai controlled the Gulf of Mannar, well-known for pearls. Going upwards on the East Coast, the ports described were Colamandala, Kaveripattanam, Poduca (Pondicherry), Masulipattanam, known for muslin, Dosarene (Odisha), famous for ivory exports, and Tamralipti (Bengal), known for muslin cloth and tortoise shells.

Names, Routes, and Locations in the Text

The Second Wave of Urbanisation- Rise of Cities and Empires (6th century BCE to 5th century CE)

The first wave of urbanisation was the mature phase of the Sindhu-Saraswati civilization (2600–1900 BCE). The second wave, also known as the Painted Grey Ware Culture, started in the Ganga valley in 600 BCE. What constitutes urbanisation? Though contested, archaeologist V.G. Gordon Childe enumerates a few criteria: cities larger and denser in size and consisting of non-food producing classes; farmers cultivating the land outside the villages; cities supported by agricultural surplus; the king collecting the surplus as tax; cities having monumental structures; recording data and predictive sciences like astronomy becoming important; evolution of writing systems, arithmetic, grammar, arts, and crafts; providing of raw materials and state protection to artists and craftsmen; flowering of brisk trade and economy; forming of long-distance exchange networks; and money economy replacing a barter system.

The widespread dissemination of iron technology; the growth of agriculture; the rich alluvial soil of the Ganga plains; coalescing politico-geographical units; and the support of Buddhist and Jain traditions in trade and commerce were the different factors that led to the second wave of urbanisation in the Ganga valley in the 6th century BCE. There is a possibility of kings establishing central cities and then spreading centrifugally. A city could be an administrative, political, religious, or economic centre.

Villages (janapadas) combined to form the Mahajanapadas, which have clear references in the Mahabharata, Buddhist, and Jain texts. Each of the sixteen Mahajanapadas had a capital city. In the 6th century BCE, Campa (Anga), Rajagriha (Magadha), Sravasti (Kosala), Saketa (Kosala), Kausambi (Vatsa), and Varanasi (Kasi) were the six great cities. By the 6th century BCE, there was an established inland trade, mercantile guilds, and caravan merchants.

King Ajatasatru of Magadha (5th century BCE) founded the city of Paṭaliputra (modern Patna) on the banks of the river Ganga. Magadha emerged as the largest and became an empire under Chandragupta Maurya. Second urbanisation attained its zenith during the Mauryan kings (322 BCE–185 BCE). The increasing population settled along the tributaries of the Ganga too. The population of Pataliputra was around 2,70,000 in the Mauryan Age. Other important cities were Taksasila, Kausambi, Mathura, and Ujjaini.

The Deccan and Southern India also experienced their own phases of urbanisation under the rule of the Satvahanas, Cholas, and Pandyas. Many Mahajanapadas had their own full-fledged silver currency. The second urbanisation until the 4th to 5th centuries CE showed great progress in astronomy, arithmetic, and geometry. The science of grammar, the six systems of Indian philosophy, and the non-orthodox philosophies were advanced and well-established during this period.

In the next part, we shall look at the Indian economy during the mediaeval period, dominated primarily by Islamic rule in the north. We shall also look at the impact of colonialism on world order. The new-found principles of nation-states kicked off a huge expansion of colonial powers, causing many disruptions, including economic ones, to the world. Europe was the epicentre of these colonial projects. The British replaced Moghul rule, and both impacted India in many ways.

…Continued in part 2

Leave a Reply