The founding father of modern economics had essentially copied Kautilya's work without giving any credit.

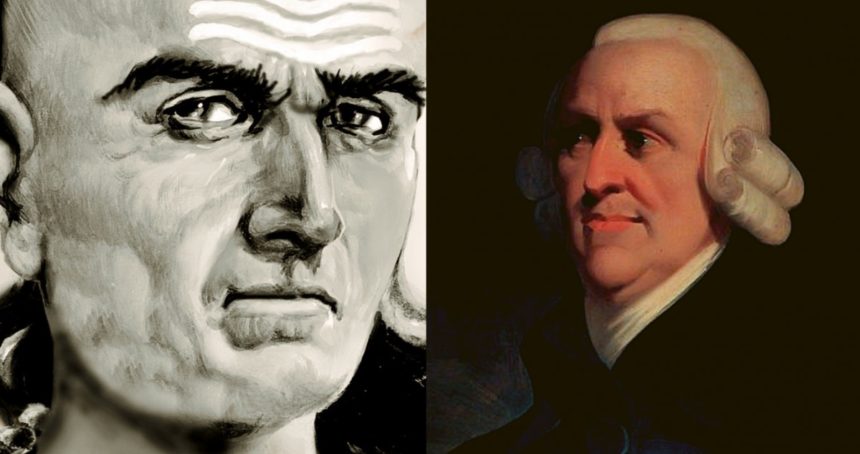

The untold foundations of Modern Economics: Did Adam Smith plagiarise Kautilya?

One of the fathers of our civilisation who never got his due is the Brahmin Kautilya. His name is discussed as a prop or showpiece in foreign policy circles while in popular culture, he is restricted to railway bookstalls selling booklets on how a woman’s sexual urges are multiple times that of a man.

On the contrary, Professor Balbir Singh Sihag has consistently hit the bull’s eye by positing Kautilya in the realm of economics. His latest work is a refreshing take on how Kautilya tackled the big questions of Economics; Moral Hazard, Poverty and Systemic Risk. His work has always revolved around a broader theme, positing Kautilya as the thinker who has been unceremoniously ignored as the father of economics by the West. People who aped and imitated him were raised to the pulpit without giving him due recognition.

His 2014 book on Kautilya showed that his work on economics precedes that of Adam Smith by two thousand years. His latest book expands to show that most of the chapters of Wealth of Nations are just blind copies of chapters of Arthashastra. This copy must have travelled to Imperial Britain where it was copied and destroyed by Adam Smith himself.

This claim is backed up by showing how Adam Smith was called out by Fergusson for copying the example of Pin factory and the entry ‘Division of Labour’ given in French Encyclopédie.[1]Smith burned his sources so that others did not find them. It is now generally accepted that Smith’s grand work does not contain a single original idea. [2]Sihag then goes on to show three irrefutable textual pieces of evidence that tell how Smith borrowed from Kautilya.

- Kautilya’s four canons of taxation are identically reflected in Adam Smith’s work.

- Somehow, Adam Smith reaches the same conclusion that Kautilya held, that i) Land, ii) Labour and iii) Capital are the three sources of wealth.

- Adam Smith follows Kautilya in lecturing how monopolies are undesirable.

One is always tempted to write more on this aspect but that would be akin to giving away the spoilers of a movie.

Sihag had already demonstrated in 2014 that Fibonacci was no financial engineer and his accounting techniques were learnt from India. He shows here how Kautilya was the founder of double entry bookkeeping. Fibonacci’s ‘Liber Abaci’ was more about calculations than about concept. Kautilya, on the other hand, talked of discounting as a central concept.

Other than Samuelson’s 1964 work, no other financial theorists talked of investments in projects that enhanced national security[3].Kautilya’s sharp economic reasoning was that such investment reduces the probability of political instability and thus lowers the risk premium.

Kautilya was the forerunner of statistical and mathematical economics. Sihag notes Vishalaksha, Kautilya’s predecessor as a champion of inferential statistics and of cognitive division of labour. He thus shows how Kautilya championed the use of statistics for informed decision making, Kautilya was a votary of population census and land surveys. Similarly, Kautilya’s exchange and conflict theory are driven by mathematics. Sihag walks us through examples where Kautilya uses discrete marginal analysis for maintaining parity with a potential adversary. Kautilya had also used combinatory rules to list all possible options and also the order in which to examine the implications of each option.

Even when the political-economic divide is breached, Machiavelli is no match for Kautilya. Kautilya’s solutions and advice are people-centric while Machiavelli comes out as a petty courtier whose job seems to just protect the King over the people.

The question then one might ask is; What was the real Kautilya like? The answer is a man who thought of ethics, Dharma, well-being of all, Yogakshema and who saw the economy not as a system but as a vehicle that leads to shared prosperity.

Sihag thus amply writes on Kautilya’s Indianness before he ventures to reclaim his works from the jaws of the West. “An ounce of ethics is better than a ton of laws” said no western economist ever. Kautilya never envisioned the King to be a maker of rules but as an investor who has the choice to be wise and invest in the society to leave behind a prosperous realm. Such a person is Rajarshi, both a Raja and a Rishi.

Adam Smith’s principle of self-interest is limited in scope, it just shows how private interest contributes to the public good. However, Kautilya does not believe in such narrow conceptions. He also talks of cases where private interest does not lead to public good; like monopolisation, lobbying, etc. He then talks of public good that does not attract private investment; like internal security, defence. A fourth category of activities which harm both the public and the private; murder, sexual assault, insider trading. These are done at the heat of the moment but are born of greed, lust, jealousy, addiction and similar vices. Kautilya actually makes a list of rulers whose downfall were intertwined with each sin.

Thus, he was deeply interested in a society of ethics, Dharma. Shared prosperity from markets is only possible when the whole society was on the same page, following their Dharma.

Kautilya was well aware of the dangers of a market without rules. Farmers get low prices because of monopsony, consumer pay high prices because of monopoly, hungry workers are never able to negotiate better wages. His rulemaking prescriptions were always thus to overturn market asymmetries. Sexual harassment and child labour are outlawed. This, when his Greek counterpart Aristotle who wrote on justice did precious little against slavery. Sihag analyses each of his policy prescriptions under the lens of economics, how they simultaneously promote growth and inclusion in society.

Kautilya saw corruption as a moral hazard and a systemic risk. He does not treat the economy as a mechanical system that can self-propagate. He rather sees it as a dynamic phenomenon which is chaotic in nature, the small and petty indulgences often form a circular loop, create a reward mechanism of its own and ultimately collapse the entire society together.

His prescriptions of curbing corruption are squarely in the realm of Game Theory, he prefers an incentive structure that promotes co-operation and honesty rather than defection and cheating. Kautilya is but very aware that the institution and rule makers themselves may be given to corruption. Thus, nothing can substitute the teaching of ethics in society. The place of moral value is simply irreplaceable in Kautilya’s schema.

Professor Sihag’s work is a landmark in the formation of an Indian Grand Narrative. It explains that the economic history unearthed by Agnus Deaton is not an accident. It is soundly rooted in Indian philosophy. Sihag gifts to us a polished version of Kautilya that was neatly buried by the Establishment. His work shows how Kautilya made Arthashastra a secular science by dissecting it from Hindu theology. This can be very easily understood if we position Kautilya in the midst of the Mimamsika movement when Brahmins were trying to critically investigate their Vedic lineage from a dominant ascendency of Buddhism.

However, Kautilya thus also acts as a lens through which we present-day Indians can get a glimpse of India’s past. Religious concepts like Chakravartin, that see the Hindu emperor as an epithet of Narayana in the midst of the cosmic ocean is transferred to the secular, the Chakravartin as a seasoned investor ruler who can successfully make the whole society prosper by traversing the tides of the market. Dharma acquires more ethical connotations than religious while Yogakshema is not left to divine intervention (as in Bhagvad-Gita) but is left to the secular ruler.

Thus, this book is a must read for all persons interested in India’s grand story.

Available here: Kautilya on Moral Hazard, Poverty and Systemic Risk

References:

[1] A good summary of the incidents as it unfolded can be found here. http://www.independent.org/publications/article.asp?id=2765

This is a version of the original article; Hamowy, R. (1968). Adam Smith, Adam Ferguson, and the Division of Labour. Economica, 35(139), new series, 249-259. doi:10.2307/2552301

[2] Barber, W.J. (2009 [1967]) A History of Economic Thought. Published by Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT 06459.

Page 50 of the book reads, “Little of the content of The Wealth of Nations can be regarded as original to Smith himself. Most of the book’s arguments had in one form or another been in circulation for some time.”

An e-copy where the text is in page 26 can be accessed here; https://www.etcases.com/media/clnews/14323565381395774180.pdf

[3] Jorgenson, D., Vickrey, W., Koopmans, T., & Samuelson, P. (1964). Discussion. The American Economic Review, 54(3), 86-96. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1818492

Leave a Reply