Introduction

‘A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots’, said the fiery African-American nationalist Marcus Garvey who led a movement at the turn of the 20th century for repatriation of black Americans and Jamaicans to Africa. Although criticized by many leading voices of the civil rights movement in the US for his extremist views, his calls found resonance with a large number of people, plausibly since they seemed to appeal to the inherent sense of individual honour. In any society where tradition and cultural ethos are cornerstones, a perceived threat to the sanctum of societal belief provides ample occasion for the combination of political opportunism and an almost parasitical media dependency, metaphorically speaking, on amplifying intra-societal divisions, to exploit the metamorphosis of the problem into a perceived assault on individual honour.

There is a case to argue that the cause for the persistent discord between liberals and conservatives in India lies as much on the liberal intellectual exclusion of the cultural and traditional systems of India, as perhaps on the straitened views of the conservative.

Historical Affirmation

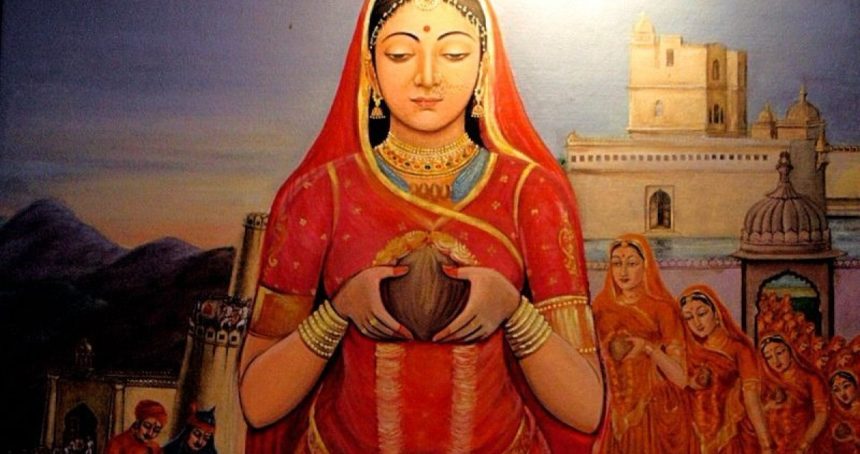

The history of Mewar, from Rani Padmini to Maharana Pratap, has often been the focal point of dispute, and taking the agitation over the movie Padmaavat as a case in point, we find voluminous evidence of mutual exclusion being the root-cause of the friction.

The anger over the Padmavati issue palpably shifted quite a degree to, and was fuelled by, the questions raised on the validity of Rani’s very existence, and for good reason. Several leading liberal opinion makers, as also some leftist historians went on television claiming there was no historical evidence, whatever that constitutes, to show Rani Padmini actually existed. This became the central theme of the debate, lent copious airtime on Prime-time TV, fuelling the shift of dissonance to questions on ancestry and history of an individual community.

Let us first examine the insufficiency of the claim that there is no historical evidence of Rani Padmini’s existence. Amir Khusrau, the Sufi scholar and poet who attended the court of emperor Ala ud-din Khalji, at the turn of the 14th century composed an extensive work – much of it a eulogy, on Ala ud-din’s military conquests, called Khaza’in ul-Futuh (Treasures of Victory).

When Alu ud-din commenced his tour of conquest, by his own admission in pursuit of becoming the second Alexander of Macedon, Khusrau, tagging along recorded events as their forces went pillaging land after land, fort after fort. His description of the sack of Chittor, 1303, is thus the only known record left by an eye-witness to the event.

He writes, as if speaking directly to those who, 700 years later questioned the Rani’s very existence

“On Monday, 11 Muḥarram, A.H. 703, the Solomon of the age, seated on his aerial throne, went into the fort, to which birds were unable to fly. The servant (Amīr Khusrau), who is the bird of this Solomon, was also with him. They cried, ‘Hudhud! Hudhud!’ repeatedly. But I would not return; for I feared Sultān’s wrath in case he inquired, ‘How is it I see not Hudhud, or is he one of the absentees?’ And what would be my excuse for my absence if he asked, ‘Bring to me a clear plea’? If the Emperor says in his anger, ‘I will chastise him,’ how can the poor bird have strength enough to bear it?”

The translator of the Persian work, Mohammad Habib, makes it simple, thus: (The above refers) to a well-known story of the Quran, Chap. xxvii. Sec2. Hudhud is the bird that brings news of Balquis, queen of Seba to Solomon. The famous Padmini is apparently responsible for allusions to Solomon’s Seba.

To make it simpler, the reference and the quotes are from the famous story where King Solomon of the Hebrew Bible (or Sulaiman of the Quran), desired and advanced upon Balquis, the queen of Seba, with the news of her subjugation to his advances brought to him by a bird named Hudhud. Amir Khusrau calls Ala ud-din Khalji the ‘Solomon of the age’ and himself being ‘Hudhud’ tasked with the responsibility of reporting from what is found inside the fort of Chittor after the siege ends, he fears facing the sultan, for the siege has ended in ignominy for the invader as the valorous Padmini, having consigned herself to fire, carries her honour intact into eternity. Khusro also refers to the fort as appearing to be Seba to the invading army. A reputed scholar, an eye-witness to the siege, making an allusion to a famous story of the advance upon a beautiful queen by a mighty emperor to singularly record events of a particular conquest, expressing fear facing the wrath of the king for failure in the quest, would appear to be as far as a Persian chronicler of the ruler of the time could go to describe an unflattering turn of events, and leaves little to imagination.

It would thus have been more fitting had those commentators who questioned Rani Padmini’s very existence made a more detailed enquiry, especially since traditionally genealogy in India, particularly for royal families has been maintained and passed on orally, as by the Charan bards of Rajputana through their doha(verses), raso (martial epics), khyata (chronicles) etc, which lack nothing in accuracy, and offer in the traditional poetic form a wealth of historical information going back centuries on lineages, battles, conquests and traditions. Mewar’s genealogy (and Rani Padmini’s along with it) is well preserved and recorded, as is that of much of the former Rajputana, in traditional literature.

Is it too much to expect opinion-makers in India to reference traditional sahitya of the country? Would the genealogy, as maintained for centuries by the Brahmins of Haridwar be palatable history to modern commentators who seem to insist, such as in the case at hand, that the clock of history started ticking with the arrival of Persian chroniclers in India? Is it fair to enquire whether the seminal work of Kavi Shyamaldass, the Vir Vinod– one of the most authoritative works on the history of Mewar commissioned by the Maharana in the 19th century, one that is founded on a wealth of traditional literature and verses, was consulted prior to pronouncements questioning the existence of Rani Padmini?

The orientalist and scholar Max Mueller through the work, ‘Rig Veda Sanhita- The sacred hymns of the Brahmans’, the famous English author James Tod, in his work Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan and a legion of others seem to have given the oral, Bardic traditions that have carried cultural history in India for centuries a great deal more respect, recognition and enquiry than many modern commentators of India.

A great example of cultural tradition surviving vicissitudes of faith is to be seen in the Tarikh-i-Sindh (History of Sindh), derived from the Tarikh-i-maasumi of Mir Muhammad Masum in the 16th century, where the Sumrahs, the ruling muslim dynasty upon perceiving the advent of the invading army of Alu ud-din Khalji, send their women and children for protection to the Sammahs, a competing and adversarial muslim dynasty, upon the advice of hindu charan bards who are held in high esteem by both dynasties taking after the tradition of Hindu rulers to whom the charans were revered courtiers.

Thus even in high strife, cultural traditions and systems did not see the kind of scorn and disdain they seems to be witnessing in some areas in modern India, where a growing tendency seems to be disallowing acceptance of cultural reality in the guise of rationality.

Iran today is witnessing a widespread call for evocation of ancient Persian culture, over and above its religious identity. Taking the Persian culture as an example, one of the greatest works of its historical literature, the Shahnameh borrows heavily from a work preceding it by 500 years, the Khwadey Namag- verses are supposed to be an important part of both these, and the distinction between history recorded in poetic verses and the more ‘conventional’ must be fuzzy at best. Important records of the life of one of the greatest Persian kings, Khosrow II (or Chosroes II) are largely fictionalized, and perhaps most were written decades after his death- however, only a myopic historical view can question the very existence of such a king.

Conclusion

No ancient history or culture could be assessed holistically through a narrow definition of formal or official history.

This argument however, in no manner should seek to justify the outrageous behaviour of some groups resorting to violence over the issue of the release of the movie. The state, and its responsibility towards maintaining law and order, is quite separate a subject from an assertion on a holistic approach to studying history.

For the study of history, one may wish to draw a parallel from a verse recited by charan bards to allay hesitation in the mind of Raja Man Singh, religious reasons, in crossing the river Sindhu as he led Emperor Akbar’s forces on an expedition to Kabul:

Sabe bhumi gopal ki, ya mein atak kahan, ja ke man mein atak hai so hi atak raha (there isn’t a bound in all the land that belongs to God, only he hesitates who is bound in heart).

History too, one hopes, is embraced with an unbounded mind.

Leave a Reply