The poems of Karnataka’s Virasaiva saints embody the deepest devotion to Siva and point us to the highest reaches of spiritual attainment.

Akka Mahadevi’s Complete Surrender

I lie awake in the small, thin-lit hours of the morning absorbed in the poetry of the 12th century Virasaivas. From nowhere, a line from Dorianne Laux’s ‘Mugged by Poetry’ comes to me. “…(When I read a poem) I end up like I always do, flat on my back like a drunk in the grass, loving the world…” Sigh. What would Laux say if she chanced upon the couplets of these poet-saints? Or, in particular, the vachanas of Mahadevi?

Akka Mahadevi, was one of the most outstanding Kannada poet-saints of the virasaiva tradition. Born in the 1100s in a small hamlet of Karnataka called Uduthadi, Mahadevi considered herself betrothed to Lord Shiva at a tender age of 10. She spent her adolescence in his worship, and composed vachanas that spilled over with fervent longings for her beloved, Lord Cenna Mallikarjuna:

“I look at the road for his coming,

If he isn’t coming, I pine and waste away,

If he is late, I grow lean,

O mother, if he is away for a night,

I’m like the lovebird with nothing in her embrace.”

“Cenna Mallikarjuna” or “Lord, White as Jasmine” is her aṅkita or signature in her vachanas. Vachanas hold a unique place in the long and checkered history of Kannada literature. Simple in diction, these are the rich, spontaneous outpourings of the socio-religious virasaivas of medieval Karnataka. Medieval Karnataka was a greatly interesting period— during this time, there stirred a great spiritual awakening in a large section of the general public, and a monumental effort was made to disseminate the principles of spiritual essence in the language of the common man— to, in fact, demystify God. The Virasaivas discouraged the blind acceptance of traditional scriptures and customs, and placed a great emphasis on personal experience and inquiry into truth. They tried to realize these truths in their own concrete life-situations and expressed them in their own distinct idiolects. They came from all walks of life— cobblers and town-criers, street performers and prostitutes, washer-men and potters, cowherds and tavern keepers. Thus, we have vachanas by minister-poets like Basavanna and Kondugodi Keshiraja, cobbler-saints like Madara Cennayya, and untouchables like Haralayya and Kalyanamma.

In general, vachanas are simple, pithy 4-8 line prose-poems that are composed in spoken-Kannada and imbued with profound philosophical ideas. Although they are format-free, and employ no regular meter or other rhyme schemes, their language is marked by certain internal rhymes and syntactic parallelisms, and thus, they combine the lucidity of prose with the rhythm of poetry. More than 20,000 odd vachanas have been composed by over 300 prominent virasaivas, and 300 odd vachanas are credited to Mahadevi.

Mahadevi’s vachanas are intense and of great lyrical depth; they sparkle with the magic and music of words, with brevity and bold imagery. In them, the core principles of spirituality are captured in a poignant tone of one intoxicated with divine love:

“I am in love with the one

Who knows no death, no evil, no form.

I am in love with the one

Who knows no place, no space, no beginning, no end.

I am in love with the one

Who knows no fears nor the snares of this world,

The Boundless One who knows no bounds.

More and more I am in love

With my husband

Known by the name of Cennamallikārjuna.

Take these husbands who die and decay,

And feed them to your kitchen fires!”

A Damsel Spurns Royal Marriage

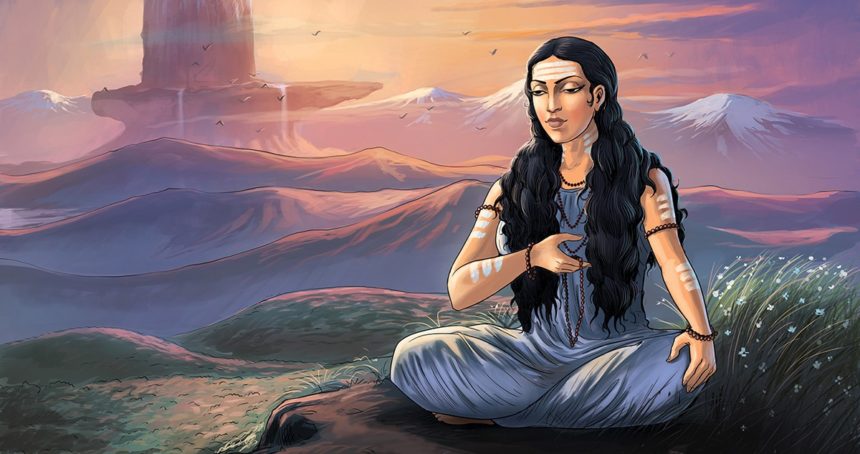

Arriving at Anubhava Mantapa: Mahadevi visits Allama Prabhu at his courtyard for devotees (Courtesy Sunil Deepak)

Through Mahadevi’s vachanas we can trace the contours of her life on her journey towards moksha, ultimate liberation. We gather that she was a stunning young beauty. King Kaushika, the ruler of the land, fell passionately in love with her the moment he saw her. But she spurned his request for marrage, “But for my Chennamallikarjuna, all men are mere dolls!” she chided the king:

Fie on this body!

Why do you damn yourself

in love for it—

this pot of excrement,

this vessel of urine,

this frame of bones,

this stench of purulence!

Think of the Lord, Chennamallikarjuna!

A persistent Kaushika threatened her family with grave consequences until she relented and agreed to marry him on the condition that he would not force himself on her without her consent. When he later failed to keep his promise, Mahadevi walked out on him. As she departed the palace, a wrathful Kaushika demanded the return of all the jewels and extravagant clothes he had presented his wife. Defiant, Mahadevi stripped herself bare and stepped out onto the streets as a digambara—a naked saint.

The last thread of clothing

can be stripped away,

But who can peel off Emptiness,

that nakedness covering all?

Fools—while I dress in the Jasmine Lord’s morning light, I cannot be shamed;

what would you have me hide under, silk and the glitter of jewels?

Joining the Assembly of Devotees

She walked on foot to Anubhava Mantapa or “Abode of Experience,” a center for philosophical/spiritual discussions in Kalyani presided over by Allama Prabhu where Virasaivas like Basavanna and Chennabasavanna congregated. When Mahadevi, wandering naked, arrived at Anubhava Mantapa, she was greeted with much skepticism. Allama Prabhu, uncertain of her spiritual competence, challenged, “Why come you hither, O woman in the budding blossom of youth? If you can tell your husband’s identity, come, sit. Else, pray, be gone!” Mahadevi answered,

All of mankind are my parents. It is they

who made this matchless match of mine

with Chenna Mallikarjuna.

While all the stars and planets looked on ,

my guru gave my hand into His;

the Linga became the groom,

And I the bride.

Therefore is Chenna Mallikarjuna

my husband

And I have no truck with

any other of this world.

Allama Prabhu interrogated her for a long time, and at the end of it, all the Virasaivas recognized Mahadevi’s worth. Allama Prabhu acknowledged: “Your body is female in appearance, but your mind is merged with God!” Thus, Mahadevi came to be accepted in their inner circles, and out of respect and affection, she came to be called Akka or elder sister.

Akka Mahadevi continued her tapas in Kalyani under the guidance of Allama Prabhu, and the vachanas composed at this stage reflect her progress.

The leaves on the apple tree,

in shapes as countless as their number,

show many shades of green,

none quite like the other.

On the rose bush next to it,

leaves and petals do just the same

and so do blades of grass,

lobelias and daisies,

each shade of color unique.

Akka Mahadevi longed

to find your face

and found it everywhere,

O Chenna Mallikarjuna!

Still revered today: a shrine to Mahadevi at Udathadi, her birthplace in Karnataka. After a few years of sadhana, Akka Mahadevi went to the famous Siva temple at Sri Sailam in Andhra Pradesh. It is said that she spent the last months of her life in various caves, completing her process of enlightenment, and attained Mahasamadhi, divine union with her Lord. Unverifiable historical records indicate that she died in her mid-twenties. Legend tells us that she was consumed in a flash of light, leaving only her poems behind as a chronicle of a spiritual journey that still evokes awe and respect in the hearts of all.

O Lord, White as Jasmine!

(Wikicommons)

Here is a sampling of Akka Mahadevi’s poems, excerpted from the book Speaking of Siva, translated by A. K. Ramanujan, available from Penguin Classics.

Locks of shining red hair, a crown of diamonds, small beautiful teeth and eyes in a laughing face that light up fourteen worlds—I saw His glory, and seeing, I quell today the famine in my eyes.

I saw the haughty Master for whom men, all men, are but women, wives. I saw the Great One who plays at love with Shakti, original to the world. I saw His stance and began to live.

The bee that was engaged all along in drinking the nectar from the White Jasmine is consumed totally in that very process. Not even the Symbol remains!

You are the forest; You are all the great trees in the forest; You are bird and beast playing in and out of the trees. O Lord White as Jasmine filling and filled by all, why don’t You show me Your face?

When I didn’t know myself, where were You? Like the color in the gold, You were in me. I saw in You, Lord White as Jasmine, the paradox of Your being in me without showing a limb.

People, male and female, blush when a cloth covering their shame comes loose. When the Lord of lives drowned without a face in the world, how can you be modest? When all the world is the eye of the Lord, onlooking everywhere, what can you cover and conceal?

It was like a stream running into the dry bed of a lake, like rain pouring on plants parched to sticks. It was like this world’s pleasure and the way to the other, both walking towards me. Seeing the feet of the master, O Lord White as Jasmine, I was made worthwhile.

Listen, sister, listen. I had a dream. I saw rice, betel, palm leaf and coconut. I saw an ascetic come to beg, white teeth and small matted curls. I followed on his heels and held his hand, He who goes breaking all bounds and beyond. I saw the Lord, White as Jasmine, and woke wide open.

Sunlight made visible the whole length of a sky, movement of wind, leaf, flower, all six colors on tree, bush and creeper: all this is the day’s worship. The light of moon, star and fire, lightnings and all things that go by the name of light are the night’s worship. Night and day in your worship. I forget myself, O Lord White as Jasmine.

Leave a Reply