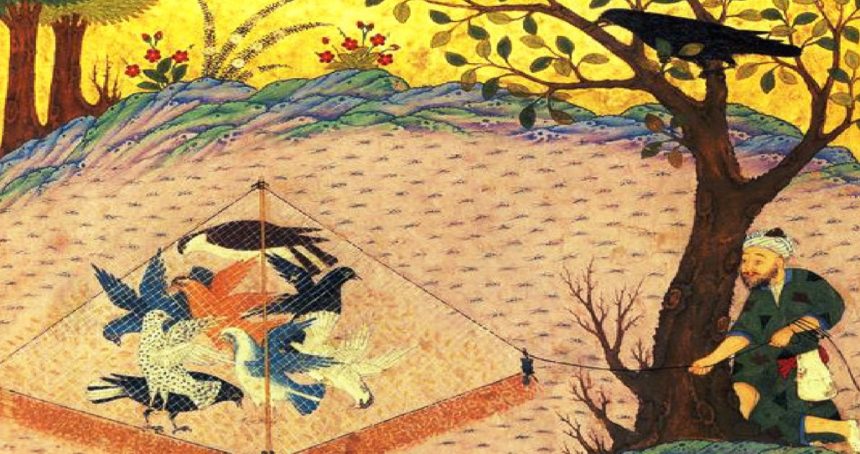

The fables of the Panchatantra have had an immense influence over world culture, with over 200 translations showcasing India's unique outlook towards life.

Vishnu Sharma’s Panchatantra

Vishnu Sharma’s Panchatantra was composed in Kashmir in approximately 200 B.C, and it is, indeed, a cornerstone of literature. A work of terrible intelligence, jest and jocularity, it is one of India’s most influential contributions to world literature. Before the invention of printing or paper, it traveled around the world a number of times, and established itself in the folk tales of multiple civilizations. In Franklin Edgerton’s words,

“No other work has played so important a part in the literature of the world as the Panchatantra… (Translated into) Greek, Latin, Spanish, Italian, German, English, Old Slavonic, Czech (and fifty other languages)… its range has extended from Java to Iceland. Indeed, the statement has been made that no book except the Bible has enjoyed such an extensive circulation in the world as a whole…Yet, perhaps it is easier to underestimate than to overestimate the spread of the Panchatantra.”

It first migrated to Iran in 6th century C.E. Borzūya, a Persian physician, was responsible for the first translation of it from Sanskrit to Pahlavi (early Persian). An apocryphal tale is found in the Šāh-nāma and in Ḡoraral-sīarthat talks about Borzūya’s trip to India— In Indian books, Borzūya had read that on a mountain in that land, there grew a plant which, when sprinkled over the dead, revived them. Borzūya traveled to India to obtain this miraculous plant, but after a fruitless search, he came across an ascetic who revealed the secret of the plant to him: The “plant” was Knowledge, the “mountain” learning, and the “dead” the ignorant. The ascetic then told Borzūya of a book for the remedy of ignorance— the Panchatantra. At that time, it was kept in a treasure chamber, so Borzūya sought the king’s permission to read it. On the condition that he would not make a copy of it, the king let him read it, but Borzūya memorized a chapter of the book a day, and when he returned to his room, he recorded what he had memorized that day, and thus created a copy of it and sent it to Iran.

Two centuries later, in 750 C.E. in Baghdad, Ibn- al-Moquaffa translated it from Pahlavi to Arabic, and almost all the pre-modern translations of the Panchatantra in Europe have their roots in this Arabic translation. In its German translation, the Panchatantra was the first Indian and the second book after Bible to be published by Gutenberg press in 1483 CE. The first English variant of it appeared in London in 1570, entitled The Moral Philosophie of Doni, taking its name from an earlier Italian translation. By 1888, there existed over seventy variants with different titles in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Spanish, German, French, Italian, English, Dutch, Danish, Swedish, Hungarian, Czech, Croat, Polish, Armenian and many other languages! Indeed, the Panchatantra can be called as the first “international blockbuster hit”!

Written in champu style — a combination of prose and verse, the Panchatantra is divided into five “tantras” or parts: (1) mitra-bheda or “Estrangement of friends”, (2) mitra-samprāpti or “Winning friends”, (3) kākolōkīyam or “Of crows and owls”/ “War and peace”, (4) labdhapranāsam or “Loss of gains”, (5) aparīkshitakārakam or “Ill-considered actions”. Interwoven together in a fables-within-fables manner, it unravels like a matroshka, a succession of Russian dolls-within-dolls. At first glance, these fables seem to be little more than animal fables with morals, intended for children. But really, the Panchatantra is a far more intelligent work than that. Its chief intention appears to be to give a glimpse of the real world in all its complex glory— the good, the bad, the ugly; the joys, the deceit, what Zorba in the book Zorba the Greek calls “the full catastrophe.” In Edgerton’s words,

“The so-called ‘morals’ of the stories… glorify shrewdness and practical wisdom in the affairs of life, and especially of politics, of government.”

Edgerton, in fact, went on to call it “Machiavellian”. Thus, in this book, ‘good’ characters lose, ‘bad’ characters win— much like in the real world; cheats and frauds quote the Scriptures to support their own nasty ends, lies, deception and deceit are in abundance. For example, in one tale is a carpenter whose wife is an incorrigible flirt. Our carpenter, with the intention of finding out if the local gossip about his wife is true, hides under her bed one night. And indeed, she takes in a lover that night, and he is filled with wrath. Before he acts, the wife realizes that he is hiding under her bed, and she promptly launches into an act herself: “Dear and honored Sir”, she tells her lover. “I went this morning to Gauri’s shrine. There, all at once, I heard a voice in the sky, saying: ‘Daughter, you are devoted to me, yet in six month’s time, by the decree of fate, you will be a widow’. So I said, ‘O blessed goddess, is there any means of making my husband live a hundred years?’ And the goddess replied, ‘Indeed there is. If you go to bed with another man, then the untimely death that threatens your husband will pass to him. And your husband will live a hundred years’. It is for this purpose that I’ve invited you”, she tells him. The carpenter, gullible that he is, is fooled, and he embraces his “faithful” wife with utmost joy!

In another tale called the “Cat’s judgment” (in the third tantra, kākolōkīyam), there dwells “on a sand-bank by the sacred Ganges — where there is sweet music from the dancing waves that intercross and break when the water is swept by nimble breezes”, a tomcat called Curd-Ear, who has assumed the life of a sanyāsi for the purpose of making an easy livelihood. Curd-Ear stands on his hind legs, gazes straight at the sun, lifts his fore-paws and delivers discourses from the Vedas: “Alas! Alas!” he cries. “All is vanity. This fragile life passes in a moment. Union with the beloved is an empty dream. Family endearments are a conjurer’s trick. But for the moral law, there would be no escape. Oh, listen to the Scripture!” Then, he promptly proceeds to eat his audience, and we are left to wonder if there were such self-styled “God-men” even two thousand years ago! Incidentally, many Panchatantra characters quote amply from classics like the Mahabharata, Ramayana, Bhagavad Gita! Arthur Ryder comments,

“It is as if the animals in some English beast-fable were to justify their actions by quotations from Shakespeare and the Bible. These wise verses are which make the real character of the Panchatantra. The stories, indeed, are charming when regarded as pure narrative; but it is the beauty, wisdom and wit of the verses which uplift the Panchatantra far above the level of storybooks.”

Thus, the Panchatantra is filled to brim with tales of greed, treachery, stupidity, deceit, adultery and loyalty. Indeed, this so outraged the foreign translators that a lot of them edited chunks of it, and added chapters wherein the evil-doers were done to death, but no such comeuppance exists in the original!

Absolutely nothing is known about its author, sage Vishnu Sharma. The Panchatantra is his only known work, and the only bit of information about him comes from a prelude in the work itself:

King Amarashakti of Milaropa, whose three sons are absolute blockheads, summons sage Vishnu Sharma and tells him, “Holy sir, as a favor to me, you must make these princes incomparable masters of the art of practical life. In return, I will bestow upon you a hundred land-grants.” Vishnu Sharma replies: nāham vidyā-vikrayam śāsana-śatenā’pi karomi … kintu tvat-prārthanā-siddhyartham sarasvatī-vinodam kariśyāmi. “I will not sell my learning for even a hundred land-grants… but to fulfill your request, I’ll engage purely in Sarasvatī-vinoda (pleasing Sarasvatī, i.e teach for its own sacred sake)” (i). In fact, he takes it on as a challenge, and tells the king, “O king! Listen to my lion-roar! Make a note of the date today. If I fail to render your sons, in six month’s time, incomparable masters of the art of intelligent living, then His Majesty is at liberty to show me His Majestic bare bottom!” Vishnu Sharma then takes the princes, tells them these stories, and fulfills his promise.

While this prelude is a charming story in itself, my personal favorite is a story in the first tantra, mitrabheda (ii): A tittibha bird asks her husband to find her a good spot to lay her eggs. The husband zeroes in on a nice spot near the ocean, but the wife is rather anxious that such a place might be dangerous for the eggs — what if a mighty wave sweeps her precious eggs away? The husband sneers at her anxiety. He says:

mattebha-kumbha-vidalana-kṛta-śramam suptam antakapratimam |

yamaloka-darśanecchuḥ siṁhaṁ bādhayati ko nāma ? ||

“Which fool would dare trouble a mighty lion— (which is) an image of Death itself”, he cries. “Who is napping after a hearty meal of a wild elephant’s forehead meat (note that it means the lion has attacked the elephant head-on, not like a coward from behind!), and thus wish death upon himself?”

But when the ocean does, indeed, swallow up his precious eggs, he actually keeps his word, fights the mighty ocean, and brings back his eggs! How he manages to do this is the stuff of legends! In his own words,

hastī sthūlataraḥ sa cāṅkuśavaśaḥ kiṃ hastimātro’ṅkuśaḥ ?

dīpe prajvalite praṇaśyati tamaḥ kiṃ dīpamātraṃ tamaḥ ?

vajreṇāpi śatāḥ patanti girayaḥ kiṃ vajramātro giriḥ ?

tejo yasya virājate sa balavān — sthūleṣu kaḥ pratyayaḥ ?

“An elephant is tamed by a mere hook – isn’t a hook then all an elephant is?

Darkness is destroyed by a lit lamp – isn’t all darkness then just a matter of 1 lamp?

A thunderbolt [which isn’t even material] destroys the very mountaintops— isn’t a mountain measured by just a thunderbolt?

Spirit alone gives strength— what is the point of physical size?”

The Panchatantra stories are much, much more than preachy tales of good-overpowering-evil. In Arthur Ryder’s words,

“(The Panchatantra) represents an admirable attempt to answer the insistent question, ‘How to win the utmost possible joy from life in the world of men’… and proposes (as an answer) a harmonious development of the powers of man— a life in which security, prosperity, resolute action, friendship and good learning are so combined to produce joy. It is a noble ideal, shaming many tawdry ambitions, many vulgar catchwords of our day!”

References / Footnotes

(i) Translation – K.V.Mohan

(ii) Credit – Sadāsvāda

Leave a Reply