The Sittannavasal rock-cut Jain caves were excavated in the 7th century CE during the Pandya rule and have some of the most vibrant murals seen anywhere.

The Vibrant Murals of Sittannavasal in Tamil Nadu

Most of us are aware of the vibrant murals of the world-famous Ajanta caves in the Aurangabad district of Maharashtra. The paintings at the Jain rock-cut cave at Sittannavasal (also called the Arivar-Kovil) are said to be second only to the Ajanta paintings, yet they are hardly known. Sittannavasal cave paintings are situated on top of a rocky hill in the Pudukkottai District of Tamil Nadu.

Right from the prehistoric ages, humans have left their mark on cave walls and rocks in the form of petroglyphs and paintings. When they settled down as a community, they started to paint on pottery. Their homes were decorated with wall art. Mural art, a form of wall art done on walls of homes, temple walls, and caves, has been prevalent in Tamil Nadu from the beginning of the Common Era, at the very least. The art requires a layer of lime paste or lime mortar over which organic and mineral-based colours are used to fill in the drawings. The Sangam era texts mention the technique of mural art, colours used and the common motifs painted. Very few murals have survived the vagaries of time and nature. The frescos at the Kailasanathar Temple at Kanchipuram, built by Narasimhavarman II, are a repository of some of the finest wall frescos of the 8th century. The themes painted in this temple are that of Lord Shiva and Gods of the Hindu pantheon. The entire sandstone surface was covered with layers of thick lime plaster. The plaster has crumbled with age, but the areas where the paintings are visible show mastery over the art. The Chalukyas of Badami (Vatapi) were also known for their temple wall frescos.

The Pallavas ruled Northern Tamil Nadu till the 9th century. The Pandyas under Kadungon had regained their power over Madurai by overthrowing the Kalabhras. The Pandyas too were temple builders and they continued the art of wall murals. The murals at Sittannavasal were made under the patronage of the Pandya Kings and by the talented painters of the Pandya lands.

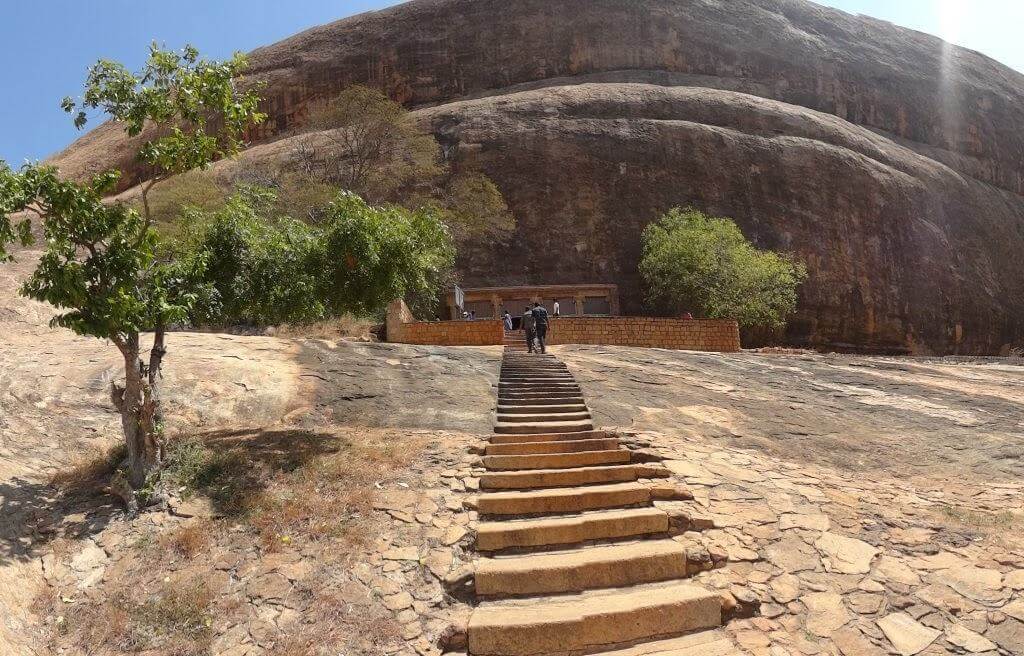

The Sittannavasal rock-cut Jain caves were excavated in the 7th century CE during the Pandya rule. The caves were cut out into the natural cavern type structure of the rock face. This was an important Jain centre for many centuries. It must be remembered that Jainism spread to South India during the 4th -3rd centuries BCE. Chandragupta Maurya had converted to Jainism and had travelled to Shravanbelgola along with a large number of Jain ascetics.

(View of the hill and the steps that lead to the caves)

The Sittannavasal cave temple was enlarged to its present structure by the 9th century CE. The outer pillared verandah that we see today was a later addition made by the Raja of Pudukkottai in the early 20th century. The pillars were brought from another temple and set within the excavated verandah. The ASI has made a gate with metal mesh. This has been done to protect the murals in the inner portions of the cave from vandalism and to ensure that bats do not enter and harm the walls and roofs.

(Pillars of the outer verandah)

The Ardhmandapam pillars give a Pallava look. The garbh-griha and Ardhmandapam are simple in style and west facing. It is the splash of colours that hits the eye, leaving the viewer mesmerised and searching for more paintings. Inscriptions on the southern side of the Ardhmandapam wall mention the history of the temple. The temple walls, pillars, and roofs were decorated with murals during the reign of the Pandya King, Srimara Srivallabha, also known as Avnipasekhara (815-862 CE). The murals were renovated and embellished and a mukha-mandapam was added in front of the cave temple by a Jain Acharya named Ilan-Gautaman from Madurai. The lintel of the outer verandah is the remains of the original mukha-mandapam.

The rectangular Ardhmandapam has two broad simple pillars and two pilasters. The beam above these pillars have corbels that give some design to the otherwise plain pillars. The outer wall on the right side has a seventeen line Tamil inscription. Such inscriptions have helped build the history of these remarkable creations. The walls, pillars and roof of this Ardhmandapam have the most exquisite surviving murals.

(The front view of the Ardhamandapam)

The upper portions of the pillars have dazzling coloured murals. The central pillars have a dancing maiden each. These maidens give the appearance of dancing in full flow and welcoming visitors at the same time. The outlines of these figures are visible along with the facial expressions and the jewels that adorn their entire body. Ochre is the most pronounced colour used for these figures.

(Images of dancing maidens)

The beam area between the Pillars contains corbels. These have striking colours with blue, green mustard, pink, brown and black being the predominant shades. Attractive lotus and swan motifs besides the floral creepers and geometric designs wow the viewers.

Just a few remnants of murals remain on the other faces of the pillars. On the side face of the southern pillar is a fading painting of two people. The outline of one makes it clear that this person must be of royalty. He is the Pandyan King Avanipasekhara Srivallaba, leading his queen to see the Madurai Acharya, Ilan-Gautaman. There are evident signs of vandalism on the surface. This was done soon after the completion of the painting as the vandal scribbled his name in the script of that era. There was a depiction of an ascetic in-between the royalty that is no more today.

(Pandyan king and his Queen)

The niches on the two ends of the Ardhmandapam have deep bas reliefs. The northern niche has a figure of a Jain Acharya seated in a meditative pose. There is a single umbrella over his head that denotes that he is not a Jain Tirthankara. As per Jain iconography, a Jain Tirthankara has three chhatris or umbrellas over the head.

The southern niche has the image of Parshvanath, the 23rd Tirthankara. He is also depicted in dhyana or meditative pose. The five-hooded Naga forms a canopy over his head.

(A Jain Acharya and Parshvanath)

The roof of the Ardhamandapam contains vibrant paintings. The paintings at the corners have deep red as the background. There are green circles with flowers (mostly lotuses) spread through the area. The red colour stands out as very attractive and gives the effect of a heavenly carpet. Only portions of the mural remain as the lime plaster has peeled off.

(A corner of the roof)

The most striking part of the roof is the central area, as a considerable portion has survived to reveal a lotus pond with abundant nature and some human figures. The more you gaze at the lotus pond, the more alive it becomes. The pond has a green hue. Fish swim in between the leaves and flowers.

(The central portion of the roof of the Ardhmandapam)

The Lotus pond is not a depiction of just a beautiful pond and nature but is associated with the Jain tradition of Samavasarana – when a Tirthankara attains ‘kaivalya gyan’.

Jainism is an ancient Indian religion that focuses on the attainment of ‘Nirvana’ or the liberation of the soul. The Tirthankaras hold the most important place amongst the followers of this faith. As per Jain traditions, there are five important events in the life of a Jain Acharya for attaining enlightenment. These are birth, renunciation, realisation (kaivalya gyan), first sermon and finally Nirvana or the liberation of the soul. The first sermon is to be given in an audience hall called the Samavasarana. Celestial beings, humans, birds, animals, fish all come as an audience to listen to the enlightened discourse. It is this broad spectrum audience of the Samavasarana that has been so well displayed on the roof and extended to the beam and pillars.

As per the Jain traditions, it is only a select few who can attend the discourse. The Bhavyas (good souls) are those disciples who have passed through several levels of bhumis or regions to occupy a seat to hear the discourse. The Second Bhumi is called the Khatika Bhumi (the lotus tank). The Bhavyas enter the lotus tank to clean their feet and collect lotus flowers, while the animals, birds and fishes also enjoy the pond.

The Central area of the roof depicts this lotus pond in full natural glory. In one area, a single Bhavya is depicted collecting lotus flowers along with the stalks. The Bhavya is immersed in the beauty of these heavenly flowers. The painting shows the lotus flower in all its forms, along with the leaves.

(A good soul collecting lotus flowers in the Khatika Bhumi)

Not far from this Bhavya are two more good souls collecting lotus flowers and preparing to hear the discourse of their lord. The skin tones of these beings are distinctly different with one as brown and the other as orange. The description of the pond is very beautiful and it is full of life. The swans are happy, and the fish look so real that you can imagine them glide near your feet. The big animals such as the tusker elephant and the buffaloes are enjoying the cool water. The swans and the ducks are a delight to see. On the whole, this part of the roof is mesmerizing and a real masterpiece.

(Animals and Fishes in the Tank)

The Garbh-Griha or Sanctum Sanctorum

The sanctum is a low roofed square area with the west-facing wall having the bas relief of three ascetics in a meditative posture. The first two from the left are Tirthankaras as they have three umbrellas above their heads. The third ascetic is an Acharya. This bas relief appears to be as old as the original cave temple and therefore predates the murals.

(Meditating Munis)

The garbh-griha is a dark palace as the doorway is small and therefore prevents light from entering. The roof has a sculpted wheel with hub and axle, representing the ‘dharma-chakra’ or the wheel of law.

(Dhamma Chakra on the roof)

This sanctum has a remarkable roof that becomes visible with the help of some artificial light such as a torch. The light will expose the most intricate patterns with red as the base colour. The roof design looks like a carpet with striped borders and ropes that create geometric patterns in the form of interwoven squares and circles. The room is always dark and therefore it is difficult to capture the look of the entire roof in one go.

The geometric pattern is not ordinary. The numerous circles display the ‘dharmachakra’ in which pairs of Gautama-Gandharas are grouped together with pair of lions. This depicts the ‘Dharmopdesa’ of the Tirthankara and the interpretation of the divyadhvani that emanated from the Tirthankara during the ‘samavasarana of the Jina’. The squares have conventional lotus flowers at their centre.

(The interwoven carpet design on the roof of the sanctum)

There are areas near the central wheel that depict beautiful lotus flowers in full bloom.

(Lotuses on the roof)

On top of this hill containing the cave with Murals, there is another cave-like escarpment with Jain Beds, where ascetics lived secluded lives. This place is called Ezhadipattam and it is on the eastern face of this hillock. The steps for going up to these caves start on the western side at the southern end of the hillock. There are 17 Jain beds with raised ends acting like pillows. There are multiple inscriptions on the cave with these beds, the earliest one being a Tamil Brahmi inscription dated to the first century BCE. Other inscriptions on these beds are dated to the period between the 7th and 10th century CE. It is evident that Jain ascetics were using this location for many centuries before the Arivar-Kovil cave was excavated. The original inscriptions referred to the names of the ascetics who performed the ritual of Sallekhana (progressive starving leading to death). The vandals have inscribed graffiti on these beds, and now the access has been barred with a steel barricade. Central and Southern Tamilnadu have many such Jain beds on top of various hills.

(Ezhadipattam Jain beds) – Wikimedia commons

Conclusion

The Sittannavasal murals occupy a very important place in the evolution of Indian paintings. Even the few remaining paintings are very impressive and these are a reminder of the glorious era when vivid and colourful cave paintings were created throughout peninsular India. The mural tradition was continued by the Cholas and some of the most intricate and vibrant murals are found within the walls of the circumambulatory passage around the Garbh-Griha of the Brihadeeswara Temple, Tanjore.

Leave a Reply