Linking Tamil with the Vedas seems to be a ploy by the wily Tambrams (Tamil Brahmins) to justify their own existence. They seek to explain their imposition of the ugly invasion-derived patriarchal casteist Aryan culture on the peaceful feminist egalitarian native Tamils by inventing a primeval Tamil Vedic culture. Or so the anti-Brahmin Dravidianist movement, in power in Tamil Nadu for more than half a century, will assure you.

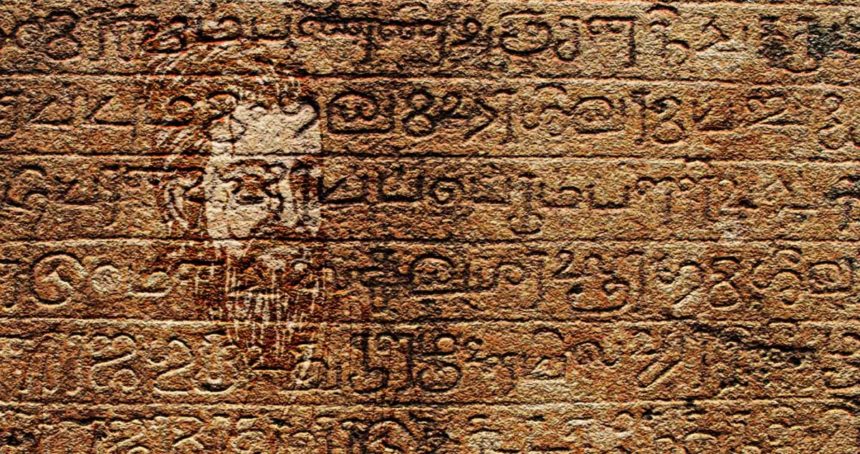

This book, Tamil Nadu: the Land of the Vedas, by R. Nagaswamy, tells a different story. The author is a Tambram alright. But he is also the foremost epigraphist of Tamil and of Sanskrit in South India. I recently met him for the first time at the book presentation in Delhi, and was struck by his enormous erudition and responsible scholarly attitude. In this authoritative 640-page book, he gives an overview of the Tamil and Sanskrit inscriptions found throughout the towns and villages of Tamil Nadu, and thereby reconstructs the true history of the region. Far from being an aboriginal zone on which the foreign culture of the invading Aryans was imposed, it turns out to have been pervaded with typically Vedic culture since the beginning of the written sources.

This is where the problem starts, for “when the Dravidian movement was at its height, (…) a claim was made that there was ‘pure Tamil’ at the beginning which was unadulterated by the Aryas.” (p.169) And in fact, that may well be true, but then long before the first texts were written. Even the oldest Tamil writings show signs of Sanskrit influence, with Tolkāppiam’s first grammar already modelled on Sanskrit grammar and Tiruvalluvar’s first poems already influenced by Vedic culture. But long before that, out of sight for us, we can still infer that there must have been a time that Tamil was spoken there, and Sanskrit or Prakrit were not.

Settlement of Brahmins

In the age well before Christ, Tamil rulers started inviting Brahmin communities to settle around their capitals and confer the prestige of Vedic civilization upon their dynasties. As soon as written history starts, we see magnates and rulers surrounding themselves with Vedic culture, witness e.g. the praise for the royal sacrifice Rājasūya yāga performed by a Cola king, by the famous poetess Avvaiyār. (p.6) In inviting a Brahmin, Tamil magnates applied four criteria: (1) he studies the Vedas; (2) he is poor; (3) he has a large family; and (4) he is honest and righteous. (p.2)

The Patiṛṛupattu poems point out that the ancient Tamil kings studied Vedas and Vedāngas, and performed daily Vedic rites mentioned as Pañca Mahā Yajñas in Vedic tradition. Avvai, the greatest poet of the Sangam age, praises the three crowned Tamil kings for performing Vedic sacrifices. All the Colakings studied the Vedas and established Vedic colleges. All the great Tamil kings of the Sangam age performed Vedic sacrifices as seen from Puranānūrupoems. In birth rites, death rites, marriage rites etc., the ancient Tamils followed Vedic injunctions. The kings appointed Vedic scholars as their Chief Ministers and presented them with lands called Brahmadāyas.

It was among the duties of Brāhmans to interpret law to the villagers. As a consequence of the brahmanization of their societies, the ancient kings followed prescriptions of Dharma Śāstra. The process of elections to Village Assemblies, the subcommittees called Vāriyams and the Paruṭai (pariṣad) system were the backbone of village life. The epigraphical wealth of Tamilnadu shows that the Sabhā system of the Vedic tradition was widely spread throughout the province. The Vedic Dharma Śāstras, esp. Manu and Yājñavalkya, were the most followed judicial texts. The technical language of these texts are used verbatim in judicial pronouncements, taken from Tamil records from earlier than the 7th century. Even the selection of judges was made after their passing an examination on Dharma Śāstra. Individual Grhya Sūtra texts like Āpastambha and Baudhāyana were the guiding principles of family life.

The most ancient Tamil grammar Tolkāppiyam followed Bharata‘s Nātya Śāstra in the division of the landscape as aintinaikaḷ. Likewise, the division of poetry into Aham and Puram based on Śriṅgāra and Tāṇdava of Nātya Śāstra. The famous text Silappadikāram is a Nāṭaka Kāvyam (dramatic composition) based on Nātya Śāstra. This was composed to glorify the Karpu(chaste) form of marriage prescribed in the Vedic system. Kaṇṇaki the heroine was married as per the Vedic rites.

Jñānasambandar

In the 7th-9th century, four principal Shaiva poets or Nāyanmārs lived, three of them Brahmins. (p.171-212) Saint Jñānasambandar, who was the greatest contributor to Tamil music and devotional literature, was a Caturvedi who was performing daily Vedic rites. Saint Appar was an agriculturist, who has rendered several passages from the Veda, especially Śrī Rudram, into delightful Tamil. Nammaḻvār‘s Thiruvāymoḻi is so replete with Vedic passages, that his poems are called “Vedas rendered in Tamil”.

The one who gets most attention here is Tirujnānasambandar, who is worshiped as incarnation of Murugan. In Madurai, though, Sambandar came in conflict with the Jains. He gave a realistic description of Jains as fasting, wandering naked, eating with their hands, shouting in Prakrit, plucking their hair, emitting foul smell because they refrain from washing themselves, cleaning their teeth or washing their mouths, not knowing the Vedas and their auxiliaries, and frequently resorting to arguments. (p.200-201)

It gets worse when they burn down his abode: “When the Mandir in which Sambandar stayed at night was torched by the Jains, he sang the heat should afflict the Pāṇḍya for not offering protection to Shaivites.” (p.198) Still he desires to engage the Jains in debate for ridiculing the Vedic sacrifices: “In two songs, he declares his intention to debate with them. He cures the king, but the Jains say that Sambandar had first made him sick with a mantra. In a fire test, his palm leaf remains unburnt; in a water test, his palm leaf flows upstream, not so that of the Jains. The Jains had first demanded that the losing side be hanged; another version is that Sambandar demand they become Shaiva, part of them do, other prefer the gallows.”

In their frantic attempts to somehow counter the Hindus’ enumeration of the countless Muslim atrocities on them, the secularists had seized upon Sambandar as the long-sought-after case of a Hindu who did to others what Muslims so royally did to them. But no, that is not what happened. Sambandar never persecuted the Jains and answered their ridiculing his own tradition with a civilized offer of a debate. He only concluded a wager with his Jain critics, viz. that the loser of the competition adopt the sect of the winner. No blood or persecution involved. It was the reigning king who saw to it that those who did not abide by the contract, suffered the self-chosen consequences.

Hundreds of songs, e.g. on each of the places of Shaiva pilgrimage, or to ward off bad planetary influences, or as a musical invitation to dance, are cited here. These often feature the Shaiva title naṭarāja: “Western Indologists (…) say the word Natarāja is found in inscriptions only from around the 14th century and so the concept of Natarāja itself is late and has nothing to do with the Vedic tradition.” But already “Sambandar says Śiva is ‘the king of dance’ (naṭam āḍiya vēntan)” which “is a definite proof to show the concept of Natarāja is earlier to 600 CE.”

Southeast Asia

The Vedas have been the perennial spring of Indian and the whole of South East Asian civilization, for the past 3500 years in almost all fields of human culture including History, Art, Architecture, Music, Dance, Administration, Judiciary, Law, Social life and so on. The rulers of Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Laos and other lands, besides all parts of India and its Northwest, have been following the Vedic laws (the Smṛtis) and personally observing codes of life which are specifically mentioned in hundreds of ancient records through the centuries. The monumental holdings like the great temples of Ankor Vat, Ankor Tom, Bantai Sri of Cambodia and the temples of Prambanam in Indonesia were mainly inspired by great Vedic Scholars. Tamilnad equally benefitted from the very beginning from the riches of Vedic lore. Śaṅkara‘s contribution to the outlook of the Tamil temple movement is discussed as seen from an inscription in a Cola temple.

Expanding Tamil culture even served as a conduit for spreading Vedic culture to Malaysia (< Tamil malai, “mountain”), Indonesia (“island-India”), Thailand (erstwhile capital Ayuthaya < Ayodhya) and Cambodia (< Kambūja, originally the name of a part of Afghanistan). Thus, in Cambodia, we find the worship of the goddess Nidrā, prayed to in the Vedic Nidrā Sūkta, long forgotten by most Indians.

Caste

After this excursus on Southeast Asia, the last part of the book (p.612-626) is explicitly about TamBrams. Yet: “It is however wrong to imagine they alone have contributed to this richness. Every section of Tamil society has produced men of greatness.” (p.626). The point is well taken, but I estimate that it will not convince the Dravidianists.

Nor will the cursory nod to some non-Brahmin castes. Thus, the Colas recognized that the country was mainly based on the rural economy and so entrusted the revenue administration of the village in the hands of officers belonging to the cultivators’ family of Veḷḷālas, conferred with the title Mūvendavelārs. The Cola kings established several Nallur as exclusive cultivators’ villages in addition to the Brahmadeyas of the Vedic Brāhmanas. This is all too transparent as perfunctory lip service to modern egalitarianism. It is like the popular Hindu reference to Śankara’s distinction between ātma vidyā (self-knowledge) available to everyone, and veda vidyā (knowledge of the Veda) exclusively available to the upper castes: a consolation prize for the non-Brahmins.

We dare to suggest, however, that the Dravidianists drop their casteist perspective and their envy in order to take pride in the Tamil Vedic heritage. As for the non-Vedic part of their heritage, no one is preventing them from writing an equally impressive compendium.

Conclusion

This book is one of the major academic contributions to the study of Tamil culture. For learners of Tamil, it can at once serve as a reader providing another view of some 2300 years of Tamil literature. Nagaswamy points out “Tamilnad continues to be the Land of the Vedas”, thus summarizing the book’s message.

——————————————————————————

R. Nagaswamy: Tamil Nadu: the Land of the Vedas, Tamil Arts Academy 2016

Leave a Reply