Nehru and Gandhiji became our (only) heroes; some like Sardar Patel, grudgingly became heroes; and the uncomfortable critics, like Subash Bose, Aurobindo, Vivekananda, and Savarkar, became either villains or pushed into oblivion.

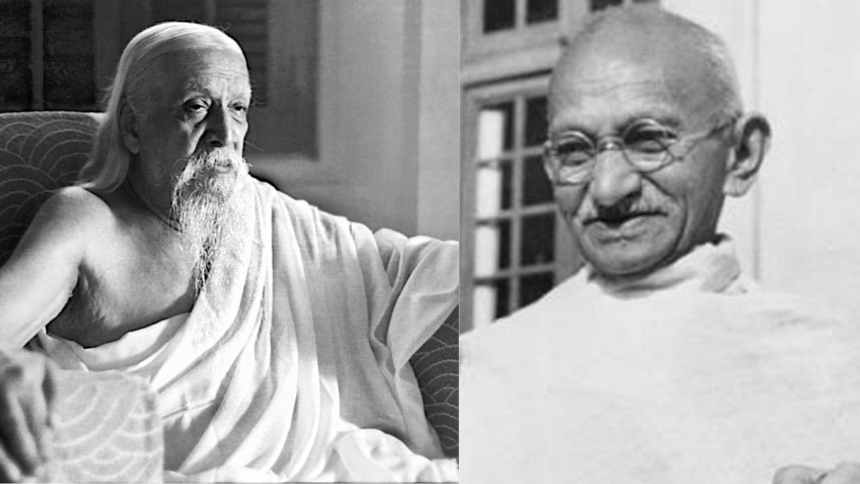

Sri Aurobindo And Mahatma Gandhi: Heroes- Forgotten And Remembered (Part 2)

In the previous part, we looked at the individual political strategies of Sri Aurobindo and Gandhiji. In the second part, we look at their varied interpretations of the Gita and their interactions and mutual criticisms at various levels.

THE INTERPRETATIONS OF GITA

Interestingly, both Sri Aurobindo and Gandhiji have their own interpretation of the same Gita. Gandhiji did not agree with Krishna asking Arjuna to fight as a justification for violence. Gandhiji believes that the Bhagavad Gita was not a historical work but a great religious book summing up the teachings of all religions. For him, the war between the Pandavas and the Kauravas was an allegory of the war in our bodies between the forces of Good (Pandavas) and Evil (Kauravas). The latter needs destruction, and there should be a constant effort in this battle. Gandhiji writes, ‘…To confuse the description of this universally acknowledged spiritual war with a momentary world strife is to call holy unholy.’

Gandhiji argues that we do not draw out swords against our relations whenever they perpetrate injustice, but rather win them over through our affection for them. Thus, the physical interpretation is incorrect while understanding Gita. The only advice given to Arjuna was: Fight without anger; conquer the two great enemies of desire and anger; be the same to friend and foe; physical objects cause pleasure and pain, they are fleeting; endure them. Thus, if one deduces that the Bhagavad Gita encourages violence, it only proves the deadliness of Kaliyuga. Gandhiji writes, ‘I have found nothing but love in every page of the Gita…’

He further adds that Gita’s message was a science of sacrifice and suffering for the cause of humanity. Gandhiji subtly states his case for the place of violence in some situations (apaddharma or emergency deviations of non-violence) but does not show any practical examples of what constitutes such a deviation in our political struggles. In giving the example of an ailing cow, he justifies violence (by giving poison to that ailing cow) to see that it dies peacefully.

SRI AUROBINDO ON GITA AND GANDHI

Writing for Bande Mataram, Sri Aurobindo laid the ideals of Swaraj (independence), Swadeshi (indigenous goods), boycott, and the doctrine of passive resistance at least a decade before Gandhi in 1905. This movement included a central organization; national education; economic independence by making Swadeshi goods; a boycott of British goods, British law courts, and all Government institutions; and a social boycott of non-responding citizens. Sri Aurobindo believed that Gandhi’s noncooperation movement was a repetition of the ‘Swadeshi movement’, but with an exclusive emphasis on the spinning wheel and the transformation of passive resistance from a political means into a moral and religious dogma of ‘soul force’ and conquest by suffering.

Sri Aurobindo, in his lifetime, was a severe critic of Mahatma Gandhi. For the former, ahimsa or non-violence was fine as a method of inner spiritual transformation, but as a weapon against dominating powers, it was weak and ineffective. At best, it could warrant some concessions from the dominating powers. Ahimsa is not the Dharma of the Kshatriya who will lay down his life and even use violent means to protect what is Truth. Ahimsa is thus a spiritual quality meant for inner transformation rather than the ideal of a nation facing many internal and external problems. Aurobindo saw Gandhi more as a Russian Christian than a true Hindu, with his concepts of Ahimsa, surrender, suffering, and acceptance of evil as a purifying experience.

Aurobindo believed that the violence of the Satyagrahi is that he does not care for the pressure that he brings on others. Gandhi’s fast to pressure the mill owners to give in to the demands of their workers in Ahmedabad without being convinced was violence on the owners. This was a repetition of South Africa, where Gandhi could obtain a few concessions by passive resistance, but they were temporary. Sri Aurobindo says, ‘…Gandhi has been trying to apply to ordinary life what belongs to spirituality…non-violence cannot defend. One can only die by it.’

Aurobindo says that he is wonderstruck at Gandhi’s claim of an infallible interpretation of the Gita. Gandhi criticizes Arya Samaj’s stand against the idolatry of image worship. Gandhi, according to Aurobindo, does the same through his idolatry of non-violence, Charkha, or Khaddar in economics, religion, and philosophy. Aurobindo believed that Gandhi’s influences were Tolstoy, the Bible, and Jain teachings; more than the Indian scriptures-the Upanishads or the Gita, which Gandhi interpreted in the light of his own ideas.

On fasting, Aurobindo writes, ‘Hunger-striking to force God or to force anybody or anyone else is not the true spiritual means. I do not object to Mr. Gandhi or anyone else following it for quite other than spiritual purposes but here it is out of place; these things, I repeat, are foreign to the fundamental principle of our Yoga.’ Perhaps, the most severe criticism comes across in a letter to one Dr. Munje, who offers Aurobindo to return to British India and to preside over the forthcoming Nagpur session of the Congress. Aurobindo refuses, of course, and goes on to write, ‘A gigantic movement of non-cooperation merely to get some Punjab officials punished (referring to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre) or to set up again the Turkish Empire (referring to the Khilafat agitation) which is dead and gone, shocks my ideas both of proportion and common sense.’

In the practical world, Aurobindo was critical of Gandhi’s appeasement policies regarding Muslims, believing that one could not possibly live with a religion whose principle is, ‘I will not tolerate you.’ Thus, for Aurobindo, the only way of making the Mahomedans harmless was to make them lose their fanatic faith in their religion. Supporting the Allied forces openly during the Second World War as a Dharmic righteous war, he had no patience with Gandhian principles of non-violence against an Asura like Hitler. Dealing only with Englishmen who wanted to have their conscience at ease was an advantage to Gandhi.

He thought of Gandhi as no less a dictator than Stalin. His word was the law in Congress, which most accepted blindly without any resistance. He indicts Gandhi for his support of the Khilafat agitation in 1921, which laid the foundation for Pakistan, and his support of Nehru instead of Patel as the first PM in 1947, against the wishes of the Congress Committee. Aurobindo was perhaps harshly prophetic when he said that Gandhiji would have no relevance for a future India. He says, ‘When Gandhi’s movement started, I said that this movement would lead either to a fiasco or to great confusion. And I see no reason to change my opinion. Only I would like to add that it has led to both.’

GANDHI AND GOKHALE; AUROBINDO AND TILAK

This website is a useful resource containing most of the articles written by Gandhi or written about Gandhi. Of course, it avoids criticism. An article by one Antony Copley makes it clear what Gandhi and his followers perceived the other movements as. Sri Aurobindo was sympathetic towards the Irish movement against the British, but Gandhi saw this clearly as a split between a parliamentarian and a terrorist approach, and ‘one which exercised an almost equal spell over Indian nationalists.’

The author does not hesitate to call Tilak and Aurobindo Ghose as closely associated with terrorism. The author does acknowledge that had Tilak lived beyond 1920, he would have posed probably an insuperable barrier to Gandhi’s taking over the leadership of the nationalist movement. Similarly, Aurobindo was the most brilliant Prime Minister India was not to have. The author writes, ‘Bengal became the centre of the terrorist movement. It is a highly dramatic story, worthy of opera, with the deeply mysterious Aurobindo as the figurehead.’ This is quite a remarkable statement. Sri Aurobindo, in Bande Mataram, dissociates himself from the rash acts of revolutionaries in Bengal and that of Madanlal Dhingra, but this Gandhian follower simply assumes Sri Aurobindo’s more solid support. This despite the fact that an intensely hostile judiciary ready to pack off Aurobindo to jail or deportation at the slightest excuse had to acquit him in the Alipore bomb conspiracy case for a complete lack of evidence.

Interestingly, the political guru and mentor of Sri Aurobindo was Tilak. Aurobindo was extremely critical of the methods of Gokhale and Gandhiji. The latter considered Gokhale as his political mentor. Gokhale received a royal reception when he visited South Africa for a period of a few weeks. Gandhi was in South Africa at that time, and he followed Gokhale during his entire tour. Maybe it was the influence of Gokhale, though never emphatic, Gandhiji did gently criticize Tilak for his more revolutionary and misguided methods, despite acknowledging him as a scholar. With regards to Sri Aurobindo, he was not quite as harsh as Aurobindo speaking on Gandhi.

In a prayer discourse on 17 March 1918, Gandhiji talks about Tilak which sums up his assessment of the Nationalists: …At present, there is only one person in India over whom millions are crazy…That person is Tilak Maharaj…He has written on the inner meaning of the Gita. But I have always felt that he has not understood the age-old spirit of India, has not understood her soul and that is the reason why the nation has come to this pass. Deep down in his heart, he would like us all to be what the Europeans are. He underwent six years’ internment but only to display a courage of the European variety…If Tilakji had undergone the sufferings of internment with a spiritual motive, things would not have been as they are and the results of his internment would have been far different… I owe it to both (Tilak and Madan Mohan Malaviya) to show now what India’s soul is. I took the vow and its impact was electrifying… The thousands of men present there shed tears from their eyes. They awoke to the reality of their soul, a new consciousness stirred in them and they got strength to stand by their pledge. I was instantly persuaded that dharma had not vanished from India that people do respond to an appeal to their soul. If Tilak Maharaj and Malaviyaji would but see this, great things could be done in India.

At one point during the Cripps mission, however, Gandhiji gets irritated by Aurobindo’s insistence on interfering in national affairs. In 1942, Sir Stafford Cripps arrived in India to seek the support of India for the efforts of World War II. The incentive was a promise of dominion status for India after the war. The Congress rejected it outright, but Sri Aurobindo wanted Congress to accept the proposal with both hands. He wrote letters to Nehru and Gandhi. The Indian National Congress turned down the Cripps Proposal which meant that Britain had to defend its Indian empire without further political or military support from India. Not only that, Congress decided to intensify its anti-British movement and gave the call for Quit India Movement.

Sri Aurobindo, though expecting a failure, was not happy at the rejection of the Cripps proposal. It is a well-known view which includes those of senior Congress ministers later that had the Cripps mission succeeded, the partition would have never happened with its tragic consequences including the Kashmir quandary. The colonial and the Moderate Congress narratives almost fixed this idea of clubbing people like Sri Aurobindo, Tilak, Dhingra, Bhagat Singh, Savarkar, and Godse in the same category of extremists. Post-independent Indian intellectual narratives continued the same theme unfortunately. Nehru, in a letter to Lakshmi Menon (1958) writes, ‘…Nevertheless, I do not consider the atmosphere generated in that Ashram (the Aurobindo Ashram) as very desirable. No doubt they are pro-Indian now but they have been very anti-Indian in the past. ‘Assuming the letter as authentic, this is an extraordinary claim (on perhaps the members of the Ashram and not Sri Aurobindo himself) without citing any evidence.

A DESIRED MEETING WHICH NEVER HAPPENED

Gandhi coming back to India turned the Congress back into the hands of the Moderates. Interestingly, the two great sons of the soil, despite being contemporaries, never met each other. Gandhiji did send his son Devdas to meet Aurobindo, who asked Aurobindo for his views on non-violence. Aurobindo simply asked if Afghanistan decides to invade India, how can non-violence counter it? There was silence for an answer. In 1934, Gandhiji was passing through Pondicherry on an all-India tour. He wrote letters with deep humility to visit the Ashram and meet Aurobindo and the Mother. However, Aurobindo politely refused, stating that he was in a state of sadhana and was meeting his disciples for a silent blessing only three times a year. It was simply a matter of his sadhana.

Gandhi was disappointed and when talked about this, Sri Aurobindo replied, ‘I suppose the disappointment was nothing more than a phrase—meaning, I would so much have liked to see what kind of a person you are. If I have read his last letter to Govindbhai aright, his request was dictated by curiosity rather than anything else. If anybody expected him to come here seeking for Truth, it was absurd—he has his own fixed way of seeing things and is not likely to change it.‘ The rationale behind this stubborn reluctance to receive Gandhi becomes apparent in a subsequent letter that Gandhi wrote after meeting Govindbhai. It seems that the British were closely observing the Ashram. Sri Aurobindo did not want any trouble for himself or for Gandhi from the British or the French authorities in control of Pondicherry. Whether this explanation is true or not, or whether there were other reasons, we will never know.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

A contemporary of those times, BC Chatterjee, wrote a book in 1921 (Gandhi and Aurobindo) critiquing Gandhiji’s non-violent non-cooperation and predicting that it would fail for sure. He was a follower of Sri Aurobindo but was deeply respectful of Gandhiji. He writes that politics is the relationship between man and man- an imperfection with another imperfection, while spirituality is the relationship between man and God- an imperfection with perfection. One cannot bring the spirituality of Gandhi into such practical matters as politics, where it was bound to fail. He makes a plea to stop the non-violence program in light of the previous experience of Aurobindo, where passive resistance even led to more revolutionary methods. Sri Aurobindo pleaded for a stop to these methods with the Montagu–Chelmsford reforms, promising to give partial Swaraj to India. The partial Swaraj or more involvement of the people of the country in the administration would be a good stepping stone to total Swaraj, according to Aurobindo. However, Congress, under the guidance of Gandhi, totally rejected this proposal. Perhaps, accepting Aurobindo’s advice would have ensured a different trajectory: an earlier independence and avoidance of a traumatic Partition.

Can we compare Aurobindo’s and Gandhi’s methods? One can spend a lifetime studying only Gandhi or only Sri Aurobindo and yet remain insufficient in understanding them. A detailed recent attempt is a book (Mahatma Gandhi and Sri Aurobindo) edited by AK Giri. This is a wonderful collection of essays discussing their thoughts on a number of topics- social, political, philosophical, religious, and literary.

Perhaps Aurobindo had more clarity of vision in his fight against the British. His passive resistance was arguably more methodical in its ideals, in placing the role of actual violence, and in defining the end point of the resistance when the British decided to make way for partial freedom. This partial freedom would later lead to total freedom. Like Gandhi, he also never allowed the place of hate in the scheme for a violent attack on British officials. However, he was practical enough to see that love could never conquer the hate of the opposite side. Gandhi’s heart was certainly in the right place and his methods to avoid the division of the country on caste lines when the British proposed separate electorates for the Depressed Classes stamps his permanent place in Indian history. His almost single-handed win against the Communists gaining control of the country also makes Gandhi an extremely important figure.

Sri Aurobindo’s politics saw the problem of Hindus and Muslims in a more realistic manner. He knew that unity would almost be impossible unless the change comes from the side of the Muslims by becoming more tolerant. Gandhiji had an emotional-sentimental approach to trying to appease the enemies or the Muslims in order to achieve harmony. In this effort, all the demands were on Hindus, the community which was his true follower ironically. Only love was the solution for Gandhiji, but Sri Aurobindo tempered his love with the detached violence of Arjuna while fighting a war for self-defense. His support of the Allied forces was an example of this, and so also the need for controlled aggression while trying to take the British. Fortunately, both could see the independence of India while still alive.

Gandhiji’s writings consist of 100 volumes, Sri Aurobindo’s writings comprise 30 volumes, and Swami Vivekananda’s writings are in 9 volumes. We grew up with Gandhi during our education, imbibing and internalizing what he had to say and what others said about him in a positive manner. Not taking away anything from the greatness of Gandhiji, the only thing we knew about Swami Vivekananda was his Chicago address, which began with ‘Sisters and Brothers of America…’. And we studied nothing about Sri Aurobindo and his most profound insights into Indian culture. Both Sri Aurobindo and Gandhiji looked at our past as a solution for the future. But broadly, Gandhiji subscribed to the view where the past is ‘simple and clear’ and the future ‘advanced, complex but evil’. This partly explains his ‘return to the villages’ as a solution and his anti-industrialization stand. Sri Aurobindo held the Indic idea of a cyclical history where the past did not equate to primitive and simple; it could equally be complex or advanced and hold solutions. In fact, Sri Aurobindo writes that India, unlike other civilizations, started at the highest levels of the Vedas and Upanishads, then came a period of shastras where every material aspect of the world became a route to reach the highest (spiritualization of the material), and finally came the period of degeneration. A return to the past did not mean a return to the primitive for Aurobindo. Thus, placed in the context of the past, neither industrialization nor “modernity” spelled disaster the way it perhaps did for Gandhiji.

The deracination and derooting which we see today extensively amongst the Indians here and abroad might have been minimized a great deal had we included Sri Aurobindo in our curriculum. It was indeed a lost opportunity as we not only neglected our ancient traditional culture holding solutions for the entire humanity but also the modern voices who could cleanly transpose the relevance of the Indian past to lay the path for a golden future. Post-independent India was a disaster mix of Nehruvian socialism and Gandhian ideals. There was a gradual rejection of the latter too, as our thinkers only applied lip service to the name of Gandhiji. A complete rejection of traditional India and a fascination for the West became the basis for building our future. Today, a deep colonial consciousness pervades all around us, and every single narrative (religions; castes; the ‘Aryans and Dravidians’; languages, and so on) is problematic and divisive. Yet, instead of developing our own understandings, we continue to sink deeper into the quicksand.

An education system that presented a linear narrative of our freedom movement with near obliteration of other factors and voices apart from Gandhiji and Nehru almost amounts to a massive deception of the country for a long time. It was a studied belief or projection of the Congress, including Gandhiji, that they were singlehandedly responsible for independence. His statements at the cusp of independence completely brushed away the role of other factors in gaining independence. In one speech, he mentions that the British actually left voluntarily and justifies the Union Jack on the Indian flag as proposed by Lord Mountbatten. Intellectuals like Ram Manohar Lohia and historian RC Mazumdar were scathing in their attacks on narratives of ‘Gandhian Ahimsa leading to independence.

Gandhiji was a great man and so was Nehru, but we need better descriptions of our independence movement. We also need to study the writings of Sri Aurobindo. Michel Danino quotes historian R. C. Majumdar, who said, ‘Arabinda had a much clearer idea as to what should be the future politics of India than most of its leaders who shaped her destiny.’ As an amazing aspect of our history writing controlled by the victors or as an example of colonial consciousness, a few things happened: Nehru and Gandhiji became our (only) heroes; some like Sardar Patel, grudgingly became heroes; and the uncomfortable critics, like Subash Bose, Aurobindo, Vivekananda, and Savarkar, became either villains or pushed into oblivion. Hitler became a big villain, and Churchill, a bigger war criminal than Hitler with regard to his role in the Bengal famine of 1943, continues to have respect. Precisely what the British would have wanted from us when they left. To make the British and Britishers honorable and just in Indian perception when they were everything but that.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READINGS

- The History and Culture of the Indian People Volume XI: STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM by R. C. MAJUMDAR

- https://incarnateword.in/sabcl/1/the-morality-of-boycott#p1-p14

- https://incarnateword.in/sabcl/01/the-doctrine-of-passive-resistance-conclusions#p1)

- https://www.mkgandhi.org/ebks/the-spiritual-basis-of-satyagraha.pdf

- Sri Aurobindo and India’s Rebirth– by Michel Danino

- https://indianculture.gov.in/flipbook/7757- Gandhi and Aurobindo by BC Chatterjee

- Churchill’s Secret War by Madhusree Mukerjee

- http://overmanfoundation.org/jawaharlal-nehrus-letter-to-lakshmi-menon-on-the-sri-aurobindo-ashram-pondicherry/

- https://www.auromusic.org/online%20books/towardsfreedom/towardsfreedom_kittu_6.html#1

- (Prarthana Pravachan–I, pp. 260-3 129 https://www.gandhiashramsevagram.org/gandhi-literature/mahatma-gandhi-collected-works-volume-96.pdf).

Leave a Reply