Appreciating the aesthetic essence of our daily lives is more pertinent than ever as we get caught up in our materialistic pursuits.

Reclaiming Saundarya: Beauty in Everyday Life

Introduction

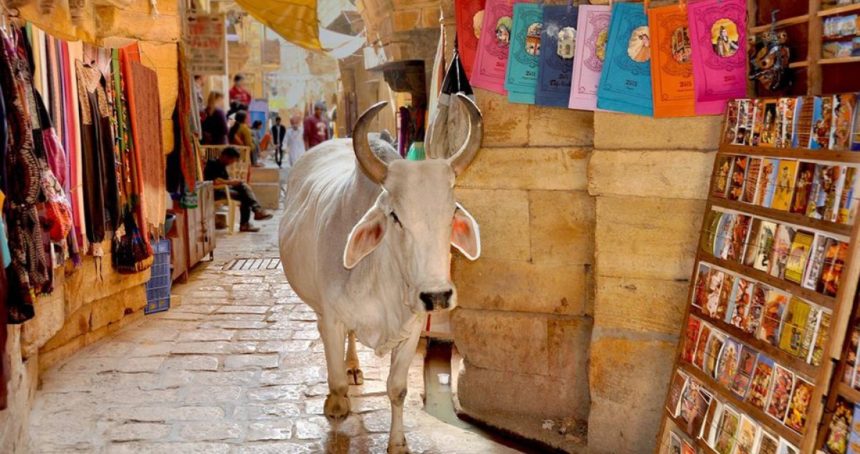

For those who have been seeking and studying the civilisational dimensions of India, the contrast between what this land has stood for and the ground reality today can be shocking. This is especially true in the sense of aesthetics and beauty, of bringing rasa into everyday life, where we are quickly descending into becoming a crude and garish people. This is not merely theoretical, but a fundamental issue that has direct implications in many dimensions of our individual and collective life. For example, to make a program like Swachh Bharat take root in the public psyche, a mere intellectual appreciation of the benefits of cleanliness will not be sufficient to bring in behavioural changes. At a fundamental level, it is only cultivation of an aesthetic appreciation of cleanliness, which creates value for having clean public spaces. One can keep multiplying examples. This essay attempts to explore how India has seen and valued beauty, what has caused this descent to the current state of affairs and what can be done to reclaim Saundarya in everyday life.

Saundarya in Rta

India has always held a special value for art, aesthetics and the notion of beauty. The Indian notion of divinity is Satyam, Shivam, Sundaram. Saundarya, or beauty and bliss that transcends all duality of pain and pleasure, happiness and sorrow are seen as the nature of the Divine. Raso Vai Sah – the Brahman or the supreme principle is described as rasa – concentrated ananda or bliss. With the entire cosmos being the manifestation of the same divine principle, rasa or beauty was seen as a doorway to transcendence, a means of one’s own spiritual evolution and a path to connect to the fundamental divine principle. Thus this worldview, far from being world negating, was a celebration of life in all its manifold richness. It was not meaningless hedonism or pure utilitarianism, which sees pleasure and self-gratification as the ultimate goal. Rather it was about the cultivation of the aesthetic eye, to see the beauty in every moment and every dimension of life, of perceiving how every single organism and every single act is yet another dancer in this cosmic Rasa Leela that sways to the rhythm of Rta, the cosmic order, around and to the tune of the Murali-Dhari – the wielder of the cosmic flute that sets the rhythm of the universe in motion. It is this vision, that saw the entire universe as the Dance of Shiva, the cosmic dance of the cosmic dancer who is in all, becomes all and pervades all. Even Pralaya, the cosmic deluge, which marks the end of this cycle of the Kala Chakra, or the wheel of time, is seen as the Rudra Tandava, the terrifyingly beautiful dance of destruction that brings awe, fear and death. It is a testimony to the inner refinement of the Indic psyche that it could see Saundarya in Rudra, the terrifying roarer of cosmic destruction; that they could see Saundarya in the terror and death that Kali embodies and see her as the Divine Mother who liberates.

Saundarya and Dharma

It is this notion of life, death and transcendence filled with and soaked in Rasa and Saundarya that breathes life into the notion of Dharma, to see it not only as an imperative to live one’s life in a manner which sustains and uplifts the individual, familial, social, national, ecological and cosmic orders, but as an aesthetic pursuit, of bringing the joy of beauty into oneself and everyone. This is an understanding of beauty, not as the objective material appreciation of inert matter but rather cultivating the sensitivity and inner refinement to perceive aliveness, the living spirit that expresses through that form or act and the harmony of that spirit and the form or act with the different orders that make up the cosmic order Rta. It is a sattvic perception of beauty not a tamasic one. This understanding of Saundarya, brings Mangala, a sense of vibrance, auspicious sacredness and joy to our everyday actions aligned with Dharma and imbues them with life and meaning. It is this eye, that brings Shradda, a deep reverence and awe, to life unfolding itself in every moment. Through all this, we become alive to and participate in the dance of life.

This depth of perception ensured that art pervaded every dimension of life in India. It was not art for art’s sake, but art as both aesthetic and useful. Every product was simultaneously a work of art and an object of everyday use. This made every profession artistic and a means of self-expression and self-refinement, a seeking of transcendence in and through the everyday. Thus every producer was a craftsman and every consumer, a connoisseur. This is why our sarees have such intricate prints and weaves, our pottery the most exquisite patterns and even buildings and supposedly utilitarian things such as step-wells have stunningly sophisticated artwork. Saundarya and rasa pervaded not only our material life, but also our social and spiritual lives, bringing Shradda and Mangala. This sense of art and aesthetics brought a sense of harmony and alignment of the prana which prevented turbulent passions from overpowering an individual. It helped individuals achieve Indriya Samyama, and well-aligned senses and well-directed action, giving them a means to explore and express their innermost self. This aesthetic sense brought meaning and value into everyday life and the every day became the path to transcendence.

Understanding Our Situation Today

When we look at India today, especially urban and urbanising India, the contrast could not be more stark. We have somehow metastised into a crude and garish people. Our roads are littered, our walls are splattered with paan stains and we couldn’t seem to care less. A spirit of vandalism has become ubiquitous and pervasive, not sparing anything from public property to millennia-old monuments. The same spirit has unfortunately pervaded our social and even political lives as well. We don’t think twice about quick and dirty ways of getting things done. We have no compunctions about ‘outsmarting” others be it in queues or in life. Politics needs no explaining. Even the spiritual dimension of our lives has not survived this onslaught – there is a sense of cynicism, of transaction and using spiritual processes as a shortcut to achieving worldly success. Gurus face questions like – “I’m spending a week here. Will I become enlightened?”. Our societal role models, a good indication of our value systems, are increasingly shifting from those who renounce and serve to those who are seen “living the high life”. Our aspirations have become filled with friday nights, flashy cars and big condos.

Understanding why this has happened to us is crucial for an appropriate diagnosis of the situation. It is only with the right understanding can we look at appropriate mechanisms to remedy it. These are some possible reasons:

1) A Vandalised Defeated Civilisation – A thousand years of invasions, conquest, defeat and desecration followed by the colonisation of land and minds has left a deeply wounded Indic psyche. There is a deep sense of defeatism, insecurity and a loss of self and collective worth. When a sense of collective worth is lost, we don’t connect to our familial, cultural, civilisational, linguistic and social identities. This naturally creates a sense of indifference and neglect to what happens to society, people and nation. They mean nothing beyond a pure utilitarian valuation. When there is no sense of self-worth one does not value himself and has no self-expectation of certain standards from himself. Freed of this, all that is left is pure instrumentalist means with no aesthetic, ethical, dharmic sense to achieve purely utilitarian purposes of survival, power, pleasure maximisation and pain minimisation.

2) Lack of Purpose – This sense of indifference and neglect leads to a sense of meaninglessness and a lack of purpose – this lack of purpose and meaning means one can do anything and nothing in life. The person is reduced to a pleasure and power seeker – and whatever gets pleasure and power becomes a suitable means. A sense of nihilism pervades the psyche. The end of pleasure is the beginning of ethics. Conversely, when there is no ethical self, no dharmic self, all that is seen is a pursuit of pleasure.

3) Desacralisation of the World – A defining characteristic of Modernity is the elimination of the sacred from the world. This worldview, that denies any transcendence has increasingly found acceptance in India. If the world is nothing but inert dead matter, there is no sense of meaning and value as it is only subjective and all there is a sense of isolation and purposelessness. If there is no point in doing things, one can do them in any way he wants. There is no need or place for Saundarya.

4) Disconnect between the design of spaces and the Indic Worldview – The design of spaces comes from a very different sense of utility and aesthetic which leads the common Indian to be bewildered and confused on appropriate behavioural norms and usage of that space. The recent installation of a Kangaroo shaped dustbin in a village bewildered them as to what its purpose was. Being used to murtis, they considered this to be yet another murthi that was installed and started performing puja leading to much ridicule on social media. However, a more sensitive design of spaces would understand that for a dustbin to be used, it must be seen to be a dustbin. In many such cases, the fault to a large extent, lies with design that has no understanding of or empathy for local sensibilities.

5) Dead Urban Jungles – Our urban spaces are fundamentally dead spaces. There is no life seen apart from human life and therefore, no possibility of perceiving the inherent rtaof nature, and how each action interconnects into a larger action, how each order flows into larger orders ultimately into the universal order. To make matters worse, our urban spaces are hostile, lawless and nihilistic. Since there is no order inherent in our urban spaces, it becomes a winner take all world. Winners are seen as smart and the rest as not being smart enough to take that path. A sense of mundane practicality is seen as being consistently more “successful” over a dharmic sense, and this lesson gets reinforced. Seeing someone who evades systems, processes and social norms consistently rewarded over those who follow order, leads to a sense of contempt for the very notion of order itself. In a Rtaless universe, where is the space for Saundarya?

6) Survivalism – Such hostile spaces and generational impoverishment breed a sense of survivalism. Since there seems to be no order – political, social or cosmic, and the world is hostile and Hobbesian, then automatically animal instincts of “fear and self-preservation” and power and dominance become dominating impulses. If we let Matsya Nyaya pervade, then a sense of aesthetic is seen as a huge impractical dreamy liability, a luxury of fools and the elite.

Despite the enormous influence of these factors, Saundarya has still not been completely erased from the Indian psyche. This can be seen in the small everyday things like the everyday art of drawing complex geometrical kolams(rangoli) in front of most houses in South India. It can be seen as well in generation-defining endeavours like the construction of the exquisitely carved Swaminarayan Temple on the banks of Yamuna, a modern temple brings to life the spirit of Rasa and Saundarya of the grand temples of old. We still have the possibility of reviving saundarya in our collective psyche and make it manifest in everyday life through both systemic and individual initiatives.

What can be done At a Systemic Level:

1) Making Our Cities Aesthetic and Alive – Bringing a living presence to our urban landscapes and enabling diverse ecosystems to flourish will reconnect man with nature and eventually connect us with the notion of a cosmic order. An urban design which gives an emphasis to creating suitable energy structures through consecrations etc can promote beauty and vibrance.

2) Bringing a Sense of Transparency and Political Order – In India today everyone is by default a potential lawbreaker due to an enormous tangle of unenforceable, and even mutually contradictory laws. This automatically creates a sense of contempt for order. Making law simple, intelligible and consistently enforceable leads to a public perception of order being rewarded and disorder being punished. This would help revive the value for order.

3) Aligning Our Systems and Structures to The Indic Ethos – Importing modern systems wholesale has created a context that alienates people from the very structures and institutions designed to enhance their life. It creates an environment where their traditional ways of life lead to confusion and squalor. Design that is in harmony with the worldview, will automatically create a sense of alignment between the systems and the people, leading to individual and social harmony.

What can be done At an Individual Level

1) Kala – The abhyasa, or sustained learning and practice of Kala, be it music, dance etc, brings a certain alignment to one’s pranic system, which over time brings in one a conscious alignment with the larger social, natural and cosmic orders.

2) Bringing a Sense of Craftsmanship to our work – The nature of work over the last century has changed from being an expression of one’s Swabhava to becoming increasingly monotonous and mechanical. This kind of work alienates man from his own self. Finding ways to bring a sense of craftsmanship to the work we do, a makers culture, as some call it, makes it come alive.

3) A Personal Connect to Nature – Having a regular activity like gardening or feeding birds, brings you in direct contact with nature and brings in a certain awareness and sensitivity to rta and brings order and balance to our lives.

4) Sadhana – Having a core spiritual process in everyday life automatically makes one more aware and conscious. Sensitivity is a natural result of consciousness and sensitivity leads to an appreciation of Rta, bringing Soundarya into everyday life.

Conclusion

The civilisation nurtured and sustained by our rishis and yogis has ensured that the perception of saundarya has taken deep roots in the Indian psyche. Despite the surface dross, all is not lost yet. But as with most of our civilisational inheritance, if we do not act now, within a generation we stand to lose what had been painstakingly cultivated, refined and transmitted over generations till the point that it effortlessly became a part of everyday life. It is up to us to rise up to our responsibility.

Leave a Reply