CONSCIOUSNESS, PERCEPTION, AND DESCRIPTION OF REALITY

In the previous parts (1, 2 and 3), we saw the gross descriptions of Indian philosophy and how they differ from Western thought with regard to consciousness, perception, and reality of the world around us. In this section, we shall see the prominent Advaitic view on the notions of the Self and the non-Self. We shall also see the notion of cause and effect in the material world and how the Self interacts with the material world. It is a promise of Indian Darshanas that proper knowledge confers liberation to the striving individual.

THE SELF (CONSCIOUSNESS) AND ITS POWERS

In contemporary philosophy, the overwhelming belief is that consciousness (or awareness) does not have the power to cause anything. It is the subjective texture of experience left over after the provision of all functional explanations. For most philosophers, consciousness is a secondary outcome or emerges as an epiphenomenon of physical matter. Even the few like David Chalmers who attribute a primary nature to consciousness agree that the latter has no functional role. Indian traditional philosophy challenges this view which not only ascribes a primary nature to consciousness but also to its causal power over certain aspects of reality.

Interestingly, Socrates and Plato held the belief, like Indian traditions, of a distinct indestructible and eternal soul separate from destructible matter. However, presently, the conception of the Self is that of being an emergent property of matter disappearing at death. Western philosophy treats the ‘self,’ ‘soul’, ‘consciousness’, and ‘mind’ as the same arising from some part in the brain. The indiscriminate mixing of categories leads to muddling up many issues in philosophy, especially the mind-matter problem. Does the mind give rise to matter or does matter give rise to the mind?

The Self, as the cognizer, can never be cognized as an object. However, the self is either known by its reflection on the cognized objects (like the hidden sun inferred from the light reflecting on the moon) or most importantly, by its self-luminous nature. A robot, Artificial Intelligence, or a computer also knows, sees, listens, or converses with a living or non-living object. But additionally, we also know that we know the object. I am seeing something but I also know that I am seeing something. This is the self-luminosity of the cognizer.

In the Western tradition, the power assigned to the ‘soul’ (or the mind) is the power of thinking and reasoning which strictly stays within the ambit of cause and effect arising from matter. However, in Indian traditions, the self has three powers independent of matter and physical laws of cause and effect:

- Iccha shakti (the power of willing)

- Jnana shakti (the power of knowing)

- Kriya shakti (the power of acting)

The exercise of these powers would not reflect in the unmoving and immutable self. They reflect in the mind and the inner instruments of the self while inhabiting the physical body as a being-in-the-world. The self exercises these powers by its mere presence and not by any exertion. It is an unmoved mover.

Iccha shakti is the power of exhibiting a desire for something. Jnana shakti is the consciousness about an object itself that becomes the knowledge about that object. In Indian philosophy, there is no fundamental difference between consciousness and knowledge. Consciousness is responsible for both, the immediate knowledge arising from direct perception, and the inferential knowledge arising in a mental mode as an ideated object. Finally, Kriya shakti is the power by which the soul (or the self) can act upon external matter. The unimpeded self can act on all matter but the embodied self can only act on certain domains of the physical matter such as the motor organs of the body it inhabits. It can act on other matters of the world only by channelizing its motor organs to act. All living beings having the soul possess these three characteristics in varying degrees.

ON THE INDIVIDUAL SELF – ‘EGO’ OR ‘AHAMKARA’

The Self is attributeless. That which is without attributes cannot exist as an individual thing. Therefore, in truth, there cannot be such a thing as an individual self. The individuality of the self does not derive from the intrinsic nature of the Self; it is the result of an erroneous identification with the body. The notion of the ‘individual self’ is parasitic upon the limited sphere of consciousness reflected off the intellect and the inner layers of the mind. The limitedness of the sphere of reflected consciousness brings about the notion that the Self is within the space of the body. The identification of the Self (capital ‘S’) with the intellect explains the notion of the limited self (with a small ‘s’).

However, this does not account for the unique individuality of the individual self. The uniqueness derives from the history of the soul’s actions and experiences in the passage of time. The knowledge episodes of these experiences etch within the inner layers of the mind as a memory repository. It is the uniqueness of this repository that provides the individual self with a unique identity. According to the philosophy of Vedanta, at a deeper level, the unique individuality of a soul derives from its Adrshta, the balance of the effects of its past actions or karma. If there is no Adrshta, there is no individual self.

The Self is not the ego. The ego is the sense of I that appears in the mind and belongs to the realm of the non-self. In the Indian tradition, it is known as the ahamkara, the form (akara) of the ‘I’ (aham). The ego is the medium through which the body gets appropriated as the self. It is the ego that sustains the facade of the self being an actor in the world.

THE THREE LAYERS OF THE NON-SELF

The first and most familiar layer is the domain of gross physical objects or the objects known by means of perception. In Western philosophy, it has become problematic to maintain that perceived objects are physical objects on account of the stimulus-response theory of perception. The objects thus perceived would be subjective phenomenal objects and not external physical objects. Indian philosophical tradition espouses Direct Perception where the individual self directly perceives the external objects. The perceived world is a legitimate world of physical objects.

The second layer is the domain of ideas or ideated objects. The mind invokes the objects to appear by the mere exercise of an individual’s will. The relation between mind and matter refers to the relation between an object of ideation as it appears in the mind and the object, referred to by the same name, as it appears in the world of gross physical objects. The appearance of objects in these two layers does not pertain to two different objects but to two different conditions of existence of the same object. Thus, Indian thought resolves one of the most perplexing problems in the Western tradition- the relationship between mind and matter. In Indian philosophy, they are simply two existential conditions of an object denoted by a name.

The third layer is the domain of the unmanifest. This layer is the repository of all objects, albeit in their universal natures. Any physical or ideated object exists perennially in the layer of the unmanifest. It emerges into the world as a created object or in the mind as an imagined idea. There is no such thing as absolute non-existence of a legitimate object. Upon the destruction of any object, it simply becomes unmanifest and comes to abide in a state of formless rest. This layer is the region of universals wherein each object abides in its universal ‘form;’ paradoxically, that universal form is formless. This layer is the nothing that is cognized in the state of deep sleep. Due to its formless nature, one mistakes the third layer as the Self.

This objective reality, which consists of three layers of objects (triloka or three worlds), is the Prakriti. Purusha or the Self is the witness of the three worlds. Western philosophy does not make a clear distinction between the self and the three layers of objective reality. Thus, there is often a derailed reasoning for ascertaining the existence of the soul due to a lack of discrimination between consciousness and one of the three layers of objective reality.

THE WORD AND THE WORLD- ‘IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD’: THE MIND-MATTER RELATION

Nouns, verbs, and all other words have four stages – the para (Brahman stage), pasyanti (incipient ideation stage), madhyama (effort for articulation stage) and vaikhari (audible stage). The first three stages are beyond the grasp of an ordinary person steeped in ignorance. The para stage is like internal eternal light and by its true intuition, a man attains moksha. Similarly, the world of objects has four stages: Turiya (Brahman stage), Prajna (undifferentiated unmanifest state), Taijasa (ideated objects), and Visva (the sphere of gross physical objects). It is easy to see the one-to-one correspondence between the word and the world in Indian traditions.

The Madhyama-Taijasa and the Vaikhari-Visva correspondences are the key to grasping the relation between mind and matter. Vivarta-vada of Advaita explains the paradoxical relationship between them which is the effect arising from a cause without any transformation in the cause. It is the pre-existence of the effect in its entirety in the cause. The apparent difference between them belongs to a paradoxical power called the Maya. The Self perceives the eternal object through two different modes of cognition. The mind is an instrument to think about the object while the sense-organs are instruments for the perception of the object. It is Maya that makes the same object apprehended through the two different modes of cognition as different.

In the Indian tradition, language is coterminous with Consciousness, the Ground of the Universe, and not with any physical substrate. At its most primal level – the speech stage of para or the object stage of Turiya is luminous and the same with Brahman. Grammar can thus be a route to salvation too in Indic traditions. The ancient Greek philosopher Parmenides and recent philosopher Spinoza glimpsed something similar but they stand alone in the Western traditions.

ILLUSIONS AND HALLUCINATIONS

The distinction between perception and hallucination also remains unclear in Western traditions. A meaningful investigation into the distinction between perception and hallucination needs grounding in ideas of mind and matter; perception as objective and mind-independent; and hallucination as subjective and mind-dependent. Indian philosophy does that effectively in comparison to Western traditions. Indian philosophy says that objects that appear to us are the realm of the mind (taijasa) and the realm of the world (vishwa). Illusions and hallucinations are in the realm of taijasa and are private. Though the ‘seen’ in both taijasa and vishwa is the same object appearing in two different conditions sometimes with the same intensity and vividness, the object in taijasa is in the private realm of ideation.

The individual Self cannot manifest these objects in the realm of vishwa by its mere will. In Indian tradition it is the Unobstructed Consciousness, the Ground of the Universe, that brings forth these objects into the world and holds them in place available for public perception. This Unobstructed Consciousness is also known as Brahman, the Immutable Akshara or the Great Imperishable. An object having a Datum of Consciousness can be mind-independent if its independency stems from it manifesting in the public space without individual power to bring about such a manifestation. The idea that an object requires to be without a datum of consciousness for it to be mind-independent is an ill-begotten idea stemming from western misconceptions about mind and matter.

THE EMBODIMENTS OF THE SELF, LIBERATION, AND REINCARNATION: THE CRUX OF INDIAN THOUGHT

The Self or Consciousness is self-effulgent and reveals objects directly and instantaneously. The absence of ubiquitous perception indicates some primal covering over the self, obstructing its natural revealing power. In Indian philosophy, this obstruction is the three-layered body: mula-sharira (seed-body with nature of sleep), sukshuma-sharira (subtle-body or the realm of mind) and sthula-sharira (gross body).

The most important question now occurs. How can something arise in Consciousness – the ground of all universe, and then contain it? Vedanta explains that this paradoxical embodiment of the Self comes about not through a physical process but through a cognitive condition whereby the Self morphs as the body, as it were, and erroneously believes the body to be the self. An idea in the mind is the same as the body apprehended in the world of matter. They are both the same appearing in two different modes of cognitive presentations (mind-matter equivalence). This erroneous cognitive idea is the mithya-gnana or the illusion of Advaita.

Self’s embodiment through an erroneous cognitive condition is central to the Indian tradition; it forms a core tenet in all the six systems of philosophy with slight variations. Hence, the right knowledge confers liberation. Even when the physical body undergoes destruction, the idea of the body persists in the realm of the mind. This thinking, considering body destruction as a loss, craves for a body. This craving, along with the law of causation related to the embodied soul’s moral actions in its past births, results in the reincarnation of the self in another body.

THE EMBODIED SELF AS AN ACTOR AND THE ARROWS OF CAUSALITY

The division of all things into two basic categories, the seen (Prakriti) and the seer (Purusha), is fundamental to the Indian tradition. Ishvara projects this universe in accordance with the collective Adrshtas of beings to confer upon them the fruits of their past actions. The purpose of creation is for seeing and experiencing it. Contemporary philosophy firmly rejects all teleology (purpose) in the universe. In the Indian tradition, Prakriti, being inert, has no purpose by itself. Purpose can exist only in a conscious agent having the power of sentience, intentionality, and will. Importantly, the telos (purpose) conceived like this does not violate the laws of nature because the locus of telos and the locus of the natural laws are different.

According to Vedanta, Ishvara’s creation does not proceed through an assembly of physical parts, as in the case of the production of things by ordinary mortals, but proceeds effortlessly from His omniscience through speech. The purpose is contextual and not an unconditional truth. Brahman or Ishvara does not create the universe for fulfilling a Divine purpose; for the Divine Being is ever full.

The telos of the world arises only in the context of the Purushas that carry with them the baggage of adrshtas – the central thread around which the purpose of the world revolves. Ishvara projects the universe for individual beings to experience the fruits of their past actions. But the mere projection of the universe would be a mere witnessing of the universe and not engaging as an actor in the universe. The embodiment confers upon the Self the status of a being-in-the-world.

By its true nature, the Self, being all-pervasive, has no containment. The presence of this erroneous cognition generates a certain psycho-physical bodily structure. And when the erroneous cognition dispels, one is set free from the shackles of bondage (to the body) and to the cycles of birth and death. This is the idea of embodiment and liberation that is central to the Indian tradition. When there is knowledge of the Self as the underlying reality of the universe, this entire structure gets dissolved.

The unobstructed Self is the Ground of the Universe and the sole efficient cause of creation and sustenance of the universe. But the obstruction that prevents the nature of the Self from being known and causes the phenomenon of embodiment to arise, also hides the nature of the Self as the Sole Cause. In this predicament, the embodied Self not only mistakes the body to be the Self but also considers the causal influences that physical objects of the world exert on its body as on its Self. It also sees itself as possessed of free will by which it may exert causal influence on the world through the employment of its motor organs. Thus, the Sole Cause of the universe appears, through the prism of ignorance of an embodied being, as a bi-directional arrow of causality with regard to the world.

WILL AND THE ARROWS OF CAUSALITY

The foremost question is about the existence of will. The question is whether there exists within living beings a power to exert extra-natural force to influence the behavior of physical objects. In a purely physicalist framework, the arrow of causality would be from a physical body (or phenomenon) to another as both the cause and the effect would be attributes of physical bodies. The rejection of Cartesian dualism in contemporary culture has resulted in consciousness being relegated to a position of an insubstantial non-entity. Thus, in the physicalist framework, the arrow of causality never originates in consciousness nor does it point to it. As an epiphenomenon, consciousness is an accompaniment of certain brain processes. Contemporary scientists and philosophers take the position of the physical causal closure argument – all phenomena in the universe have solely physical causes.

The existence of will in living beings dismantles the physical causal closure argument and establishes that the arrow of causality also points from consciousness to physical objects. Consciousness can exercise will and thereby cause changes to occur in physical objects unexplainable by physical causes alone. The notion of the physical world forming a causal closure is mere dogma. The arrows of causality are not only from physical objects to other physical objects but also from the self to physical objects. It is important to understand that the presence of will as an extra-natural power does not impinge upon the validity of the physical laws. They both exist alongside each other.

ON FREE WILL AND DETERMINISM

Unfortunately, the debate on free will versus determinism has characterized the presence of will and the presence of physical causality in terms of an either-or proposition. The problem thus lies not with the nature of the causes but in the postulation that the causes acting in nature can either be physical causes or a will exercising its freedom of action. It is a mistaken notion. They both exist together, interpenetrated with one another in reality. The exercise of will does not affect the validity of the physical laws any more than the presence of a magnetic force that causes a piece of iron to lift in the air affects the validity of the gravitational force that would be acting downward on the piece of iron.

The various forces act in accordance with the laws that are applicable to them, whether physical or incorporeal, but it is only the net effect of the forces that become obvious. The question of free will is towards knowing the extent to which it would be free in exercising its powers. Obviously, the will of a living being does not have unlimited power. The power of will is limited to moving motor organs into activity, and the motor activities act on the external object in a manner that would serve the purpose of exercising the will.

The strength and vigor of the instrument (like the muscles or brain) limit the power of the will. In general, the freedom of will is like the freedom that an animal tethered to a pole by a rope has. Beyond the radius provided by the rope’s length, it finds its movement obstructed. A living being enjoys a certain radius of freedom beyond which there is a limiting of powers. The world and the external circumstances place constraints. There are also internal constraints in the form of mental predispositions whose forces and momentums have the potential “to carry off a person’s mind” and make it act along with the veneer of its desires rather than by the dictates of reason.

The force or impulse of desire caused by such internal mental tendencies can render the will a slave of its instincts and desires. Such a will is not free. It is the state of will that exists in animals and other lower beings which retain the power of exercising their wills but do so as their instincts, desires, and mental tendencies drive them rather than by the exercise of intellect. The forces exerted by mental dispositions and tendencies belong to the non-self, that is, to Prakriti and not to the Purusha or the self.

Thus, a will held hostage to the tendencies of the mind (forces from Prakriti) cannot be free. Free will must consist of exercising its powers and abiding by its own independent nature. External forces, residing both inside the body and outside, should not be able to influence its exercise. What is its own independent nature? The Self is of the nature of pure consciousness or pure knowledge. Therefore, in acting freely, the directedness of the actions that proceed from the will would be determined solely by the nature of the self, that is, by knowledge and the power of discrimination (viveka) that comes from knowledge, and not by the impulses of desire or the forces of mental tendencies.

Thus, the actions that proceed out of free will would be actions determined solely by the knowledge of the factors involved and a determination of what constitutes the right action in the situation. Mental tendencies and desires should not propel the actions. One who acts in this manner through the exercise of his free will instead of by the impulses of desire or mental tendencies is acting in a noble manner (an arya way) in Indian traditions. Acting without desire is the supreme message of all Indian scriptures.

DESIRELESS ACTION AS THE SUPREME MESSAGE OF INDIAN TRADITIONS

SN Balagangadhara explains the concept of desireless action as the supreme message of Indian traditions which stand in contrast to the ideas regarding action in Western cultures in his book Cultures Differ Differently (The chapter titled Selfless Morality and the Moral Self). He says actions are meaningless (outside of contextual interpretations) and moral actions, as actions, become appropriate within contexts only. Then the demand would be to propose one kind of action appropriate to all contexts. We also need to seek the context of all contexts and an action that is appropriate in that context. There is one such context, which is the context of all contexts – the universe. What significance does the universe lend to this individual’s actions? The answer is none. Actions have no purpose, no meaning, no goal within the ‘master’ context if one ignores the sub-contexts. At such a level, it makes no sense to ask whether some action is appropriate or not: all actions are equally appropriate, none is, and neither of the two.

Western traditions maintain that one of the characteristic properties of human actions is goal-directedness. Against this background, what does it mean to perform meaningless actions? It is to perform an action without desiring, without wanting or even without aiming at any goal whatsoever. One simply acts. All the Indian traditions put performing an action without any kind of desire, without aiming at any kind of a goal, without attaching this intentionality to human action as the highest kind of action that is appropriate at all times. Such actions constitute the most appropriate actions in all contexts. That is, a truly trans-contextual action can only be an action exhibiting the generic property of action: goal-less and a-intentional.

One ought to perform goal-less action, but human action is always goal-oriented. Consequently, how is this different from any other moral ideal that is current in the West? The answer is simple, says Balagangadhara: one ‘ought’ to be a-intentional simply because human action is meaningless action. Erroneously, and acting under false beliefs, human beings think that action is always goal-oriented. They do not see that the context lends purpose, goal, or meaning to human action. It is these contexts that make human actions appear meaningful, when in fact they are not so. To realize this truth about human action is liberation from errors. When viewed this way, choice theories of any sort would not express this notion of ethical and moral action. Total suspension of all choices is the first requirement to be a ‘moral’ (used in the sense of ‘enlightened’ or ‘liberated’) person.

CAUSE AND EFFECT IN THE INDIAN TRADITIONS: THE ROLE OF ISHWARA

The premise that the natures of physical things themselves can explain all physical processes drives empirical sciences. This is a Charvaka principle later used by Epicureans of Greece. Newton and others gave birth to the natural sciences grounded purely in the physical natures of things. However, the western world has never been able to reconcile God with the natural laws of the universe. Modern scientists tend towards Deism – God does not intervene in the operations of the world, once created. This allows incorporating belief in God without discarding allegiance to empirical science.

In the Indian tradition, how does the existence of an apparently independent universe depend on Ishvara – the sole Independent Existence? The closest example to illustrate this is a mirror reflection. The reflection does not exist without the object of reflection. In both Advaita and Dvaita, this analogy illustrates the relationship between Brahman and the world; the relation of Bimba-Pratibimba, the object, and its reflection. There is a misconception about the ontological (reality) status of the reflection. The reflection of an object is unreal obviously. However, the object called ‘image of a flower’ is real because the reflection is truly an image of a flower. All the objects of the Universe are the reflections (pratibimbas) of Ishvara but they are true to the names they are known by. The world objects are all pratibimbas with their existences derived from, and entirely dependent on, the Bimba or Ishvara – the Supreme and Sole Independent Existence.

Ishvara, through His Absolute Will, presents the various objects as causes and effects without being dependent at any time on any of these things to unfold. Yet the causality seen is not arbitrarily dependent on the whims of a capricious God. The causality is by the natures of the objects themselves as they exist signified by words in their para stage identical with Brahman. The created universe has no existence by itself except as a reflection of His omniscience. In Advaita, the ultimate relationship between Brahman and the world is indescribable because the world being no other than Brahman, there is no relation between them. But within the sphere of the duality of creation, the Bimba-Pratibimba relationship offers the closest analogy to explain Brahman’s controllership of the entire universe as its sole Efficient Cause.

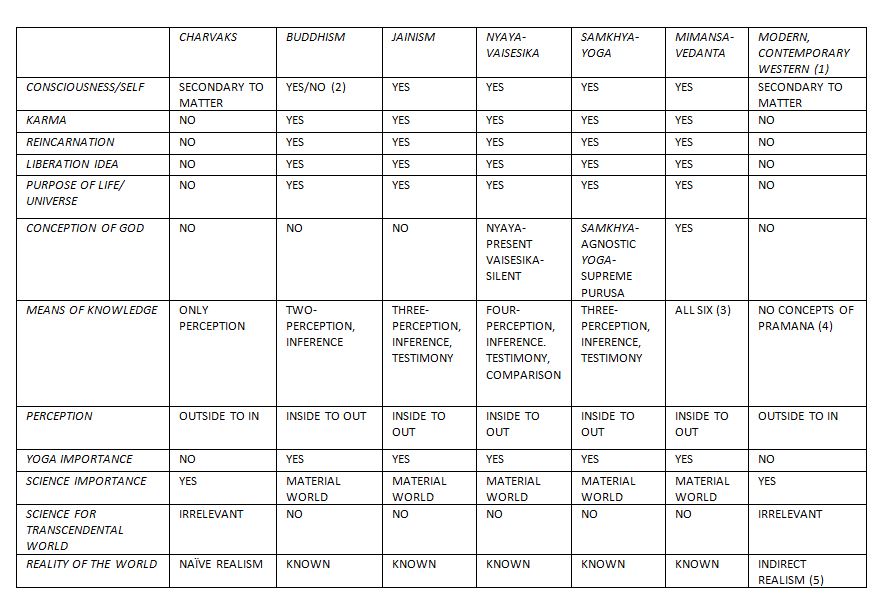

A TABLE COMPARING PHILOSOPHIES

The table and the notes have major inputs from Sri Chittaranjan Naik

These are some very broad generalizations. There are many nuances and complexities but the table is purely for the purpose of an easier grasp of the concepts.

- Western philosophies imply only modern contemporary thought and it does not include its ancestral lineage and a few ignored branches. For example, the conception of God is present in Aristotle as well as in Western Scholastic philosophy but is absent in modern and contemporary philosophy. Again, the idea of reincarnation is present in Plato, Pythagoras, Orpheus, and even in one school of Christian Patristic Philosophy (the philosophy of Origen) but is absent in all later philosophical works. The conception of the universe having a purpose (telos) may be present in Greek and Scholastic philosophies but the notion disappeared after the advent of British Empiricism (on the other hand, the philosophy of Hegel brings in a peculiar notion of a historical movement towards some grand purpose).

- Consciousness in the dominant Buddhist schools is a consciousness that flashes with objects, and in the absence of objects it is absent. Indian astika (orthodox) philosophies regard this as a kind of nihilism.

- The positions of Mimamsa and Vedanta vary from sub-school to sub-school. Advaita Vedanta has 6 pramanas but Dvaita and Vishishtadvaita believe in only 3 pramanas. Similarly, the Bhatta school of Mimamsa has 6 pramanas whereas the Prabhakara school has only 5 pramanas.

- The concept of pramana does not exist in Western philosophy. The Western definition of knowledge as justified true belief sometimes determines whether a belief (or a propositional attitude) may be knowledge or not.

- Contemporary Western philosophy may adhere to Indirect Realism (where the real world is unknown) but in the world of Science, most practitioners, i.e., scientists, unthinkingly believe in a kind of Naive Realism or a kind of Lockean Dualism. For Charvakas, Naive Realism holds good.

In the final part, we shall delve into the objections to Direct realism of Indian traditions and the replies to them. We shall also see the ingenious ways of proving the existence of the Self despite always being an eternal subject and never an object for study.

Concluded in Part 5

Leave a Reply