The maritime history of India is recounted in numerous literary texts, showcasing its navigational expertise and resultant trade with several countries.

India’s Ancient Maritime History – Part 1

We should first take into account that ancient India, which was centered around the Indus Valley years ago, and was already well developed before 3200 BCE, stretched from Afghanistan to the Indian Ocean and points farther east and north, the largest empire in the world at the time. But its influence spread much farther than that. During its peak developments, it had organized cities, multistory brick buildings, vast irrigation networks, sewer systems, the most advanced metalwork in the world, and a maritime trade network that incorporated the use of compasses, planked ships, and trained navigators that reached parts of western Asia, Mesopotamia, Africa, and other ports far beyond their borders. 1 So they were certainly capable of ocean-going trips that could have reached even to the Americas.

Prakash Charan Prasad explains in his book, Foreign Trade and Commerce in Ancient India (p. 131):

“Big ships were built. They could carry anywhere upwards from 500 men on the high seas. The Yuktialpataru classifies ships according to their sizes and shapes. The Rajavalliya says that the ship in which King Sinhaba of Bengal (ca. sixth century BCE] sent Prince Vijaya, accommodated full 700 passengers, and the ship in which Vijaya’s Pandyan bride was brought over to Lanka carried 800 passengers on board. The ship in which the Buddha in the Supparaka Bodhisat incarnation made his voyages from Bharukachha (Broach) to the ‘sea of the seven gems’ [Sri Lanka], carried 700 merchants besides himself. The Samuddha Vanija Jakarta mentions a ship that accommodated one thousand carpenters.”

Marco Polo also related how,

“An Indian ship could carry crews between 100 and 300. Out of regard for passenger convenience and comfort, the ships were well furnished and decorated in gold, silver, copper, and compounds of all these substances were generally used for ornamentation and decoration.” 2

Because of the Vedic civilization’s great reach, Aurel Stein (1862-1943), a Hungarian researcher also related:

“The vast extent of Indian cultural influences, from Central Asia in the North to tropical Indonesia in the South, and from the borderlands of Persia to China and Japan, has shown that ancient India was a radiating center of a civilization, which by its religious thought, its art and literature, was destined to leave its deep mark on the races wholly diverse and scattered over the greater part of Asia.” 3

In this regard, Philip Rawson, in The Art of Southeast Asia (1993, p. 7), further praises India’s gift of its civilizing affect on all other cultures.

“The culture of India has been one of the world’s most powerful civilizing forces. Countries of the Far East, including China, Korea, Japan, Tibet, and Mongolia owe much of what is best in their own cultures to the inspiration of ideas imported from India. The West, too, has its own debts… No conquest or invasion, nor forced conversion [was ever] imposed.”

And this is the basis for the mystery of the widespread nature of the ancient Vedic empire, which in many ways still exists today. It was this subtle spiritual dimension that spread all over the world.

Indian Maritime Trade Route

Advanced East Indian sailing in the Vedic texts

As Gunnar Thompson also explains, regarding the capability of Indian ships:

“Extensive maritime trade between India and the islands of Indonesia is well documented and illustrated. A 1st century Hindu manuscript, the Periplus, mentions two-mates ships with dual rudders mounted on the sides in the fashion of ancient Mediterranean vessels. The ships are portrayed in 2ndcentury Indian murals. Chinese chronicles of the same era describe seven-masted Hindu vessels 160 feet in length carrying 700 passengers and 1000 metric tons of merchandise. Buddhist records of a 5th century pilgrimage from Ceylon to Java report vessels large enough to carry 200 passengers.” 4

As we look at other cultures, what is often left out is the advanced nature of the ancient Indian civilization. As we look over this information, it becomes clear that ancient India had the means for sailing over great expanses of water, and also had a thriving trade industry based on shipping.

The fact is that the ancient Vedic texts, such as the Rig Veda, Shatapatha Brahmana, and others refer to the undertaking of naval expeditions and travel to distant places by sea-routes that were well-known at the time. For example, the Rig Veda (1.25.7) talks of how Varuna has full knowledge of all the sea routes that were followed by ships. Then (2.48.3) we find wherein merchants would also send out ships for foreign trade. 5

Another verse (1.56.2) speaks of merchants going everywhere and frequently to every part of the sea. Another verse (7.88.3-4) relates that there was a voyage by Vasistha and Varuna in a ship skillfully fitted for the trip. Then there is a verse (1.116.3) that tells of an expedition on which Tugra, the Rishi king, sent his son Bhujya against some of his enemies in the distant islands. However, Bhujya becomes ship wrecked by a storm, with all of his followers on the ocean, “Where there is no support, or rest for the foot or hand.” From this he is rescued by the twin Ashvins in their hundred oared galley. Similarly, the Atharva Veda mentions boats which are spacious, well constructed and comfortable.

We should keep in mind that the Rig Veda is said to go back to around 3000 BCE, which means the sailing capacity for the Vedic civilization of ancient India was well under way by that time.

An assortment of other books also referred to sea voyages of the ancient mariners. Of course, we know that the epics, such as the Ramayana andMahabharata referred to ships and sea travel, but the Puranas also had stories of sea voyages, such as in the Matsya, Varaha, and Markandeya Puranas. Other works of Classical Sanskrit included them as well, such as Raghuvamsha, Ratnavali, Dashakumaracharita, Kathasaritsagara, Panchatantra, Rajatarangini, etc.

Actually, ships have been mentioned in numerous verses through the Vedic literature, such as in the Vedas, Brahmanas, Ramayana, Mahabharata, Puranas, and so on. For example, in the Ayodhya Kand of Valmiki’s Ramayana, you can find the description of such big ships that could hold hundreds of warriors: “Hundreds of oarsmen inspire five hundred ships carrying hundreds of ready warriors.”

In the Ramayana, in the Kishkindha Kand, Sugriva gives directions to the Vanar leaders for going to the cities and mountains in the islands of the sea, mainly Yavadvipa (Java) and Suvarna Dvipa (Sumatra) in the quest to find Sita. The Ramayana also talks of how merchants traveled beyond the sea and would bring presents to the kings.

In the Mahabharata (Sabha Parva), Sahadeva is mentioned as going to several islands in the sea to defeat the kings. In the Karna Parva, the soldiers of the Kauravas are described as merchants, “whose ships have come to grief in the midst of the unfathomable deep.” And in the same Parva, a verse describes how the sons of Draupadi rescued their maternal uncles by supplying them with chariots, “As ship wrecked merchants are rescued by means of boats.” However, another verse therein relates how the Pandavas escaped from the destruction planned for them with the help of a ship that was secretly and especially constructed for the purpose under the orders of the kind hearted Vidura.

Also, in Kautilya’s Arthashastra we find information of the complete arrangements of boats maintained by the navy and the state. It also contains information on the duties of the various personnel on a ship. For example, the Navadhyaksha is the superintendent of the ship, Niyamaka is the steerman, and Datragrahaka is the holder of the needle, or the compass. Differences in ships are also described regarding the location of the cabins and the purpose of the ship itself. 6

In the Brihat Samhita by Varahamihir of the 5th century, and in the Sanskrit text Yukti Kalpataru by Narapati Raja Bhoj of the 11th century, you can find information about an assortment of ships, sizes, and materials with which they were built, and the process of manufacturing them. For example, one quote explains,

“Ships made of timbers of different classes possess different properties. Ships built of inferior wood do not last long and rot quickly. Such ships are liable to split with a slight shock.” 7

It also gives further details on how to furnish a ship for accommodating the comfort of passengers, or for transporting goods, animals, or royal artifacts. The ships of three different sizes were the Sarvamandira, Madhyamarmandira, and the Agramandira.

The Sangam works of the Tamils have numerous references to the shipping activities that went on in that region, along with the ports, articles of trade, etc. Such texts included Shilappadikaram Manimekalai, Pattinappalai, Maduraikhanji, Ahananuru, Purananuru, etc. 8

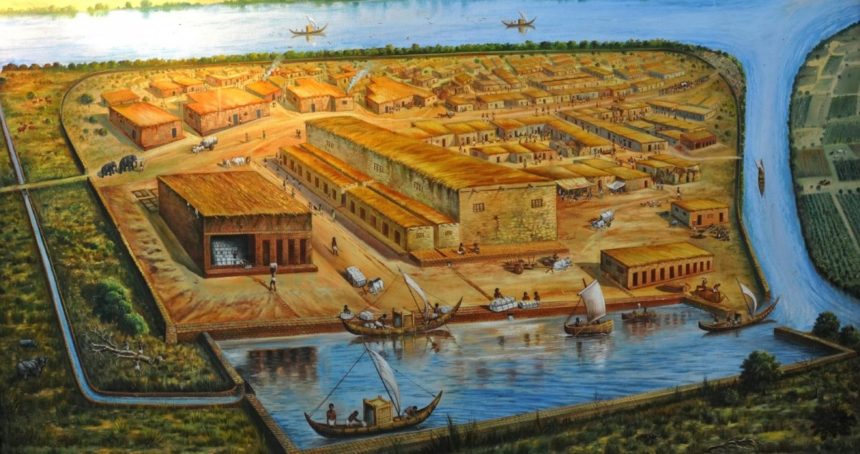

Ancient Indians traveled to various parts of the world not only for purposes of trade, but to also propagate their culture. This is how the Vedic influence spread around the world. For example, Kaundinya crossed the ocean and reached south-east Asia. From there, evidence shows that rock inscriptions in the Sun Temple at Jawayuko in the Yukatan province of Mexico mentions the arrival of the great sailor Vusulin in Shaka Samvat 854, or the year 932. In the excavations in Lothal in Gujarat, it seems that trade with countries like Egypt was carried out from that port around 2540 BCE. Then from 2350 BCE, small boats docked here, which necessitated the construction of the harbor for big ships, which was followed by the city that was built around it. 9

In the period of 984-1042 CE, the Chola kings dispatched great naval expeditions which occupied parts of Burma, Malaya and Sumatra, while suppressing the piratical activities of the Sumatra warlords.

In 1292 CE, when Marco Polo came to India, he described Indian ships as

“built of fir timber, having a sheath of boards laid over the planking in every part, caulked with iron nails. The bottoms were smeared with a preparation of quicklime and hemp, pounded together and mixed with oil from a certain tree which is a better material than pitch.”

He further writes:

“Ships had double boards which were joined together. They were made strong with iron nails and the crevices were filled with a special kind of gum. These ships were so huge that about 300 boatmen were needed to row them. About 3000-4000 gunny bags could be loaded in each ship. They had many small rooms for people to live in. These rooms had arrangements for all kinds of comfort. Then when the bottom or the base started to get spoiled, a new layer would be added on. Sometimes, a boat would have even six layers, one on top of another.”

A fourteenth century description of an Indian ship credits it with a carrying capacity of over 700 people giving a fair idea of both ship building skills and maritime ability of seamen who could successfully man such large vessels.

Another account of the early fifteenth century describes Indian ships as being built in compartments so that even if one part was shattered, the next remained intact, thus enabling the ship to complete her voyage. This was perhaps a forerunner of the modern day subdivision of ships into watertight compartments, a concept then totally alien to the Europeans.

Another traveler named Nicolo Conti came to India in the 15th century. He wrote:

“The Indian ships are much bigger than our ships. Their bases are made of three boards in such a way that they can face formidable storms. Some ships are made in such a way that if one part becomes useless, the rest of the parts can do the work.”

Another visitor to India named Bertham writes:

“The wooden boards are joined in such a way that not even a drop of water can go through it. Sometimes, the masts of cotton are placed in such a way that a lot of air can be filled in. The anchors were sometimes made of heavy stones. It would take a ship eight days to come from Iran to Cape Comorin (Kanyakumari).” 10

The famous archeologist Padmashri Dr. Vishnu Shridhar Wakankar says, “I had gone to England for studies, I was told about Vasco da Gama’s diary available in a museum in which he has described how he came to India.” He writes that when his ship came near Zanzibar in Africa, he saw a ship three times bigger than the size of his ship. He took an African interpreter to meet the owner of that ship who was a Gujarati trader named Chandan who used to bring pine wood and teak from India along with spices and take back diamonds to the port of Cochin. When Vasco da Gama went to meet him, Chandan was sitting in ordinary attire, on a cot. When the trader asked Vasco where he was going, the latter said that he was going to visit India. At this, the trader said that he was going back to India the very next day and if he wanted, he could follow him. So, Vasco da Gama came to India following him. 11

Sir William Jones, in The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society–1901, relates how the Hindus,

“must have been navigators in the age of Manu, because bottomry is mentioned in it. In the Ramayana, practice of bottomry is distinctly noticed.”

Bottomry is the lending of insurance money for marine activities. 12

In this way, Indians excelled in the art of ship-building, and even the English found Indian models of ships far superior of their own and worth copying. The Indian vessels united elegance and utility and fine workmanship. Sir John Malcom observed:

“Indian vessels are so admirably adapted to the purpose for which they are required that, notwithstanding their superior stance, Europeans were unable during an intercourse with India for two centuries, to suggest or to bring into successful practice one improvement.” 13

Mexican archeologist Rama Mena points out in his book, Mexican Archeology, that Mayan physical features are like those of India. He also mentions how Nahuatl, Zapotecan, and Mayan languages had Hindu-European affinities.

In this line of thinking, some American tribes have traditions of having ancestral homelands across the Pacific. A legend of Guatemala speaks of an ancient migration from across the Pacific to the city of Tulan. A tribe from Peru and Tucano of Columbia also relate in their traditions how ancestors sailed across the Pacific to South America. Tales of trade over the Pacific were also related to the earliest of Spanish explorers in Central America. 14

Georgia anthropologist Joseph Mahan, author of The Secret (1983), has identified intriguing similarities between the Yueh-chic tribes of India-Pakistan and the Yuchi tribe of North America’s Eastern Woodlands. The Yuchi tradition also tells of a foreign homeland from across the sea–presumably in India. 15

This information makes it clear that ancient India had the means to reach and in fact did sail to many parts of the world, including the ancient Americas, long before most countries. This is further corroborated by information in the chapter of Vedic culture in America in Proof of Vedic Culture’s Global Existence, for those of you who would like more information on this.

Continued in India’s Ancient Maritime History – Part 2

References / Footnotes

1. Lehrburger, Carl, Secrets of Ancient America: Archaeoastronomy and the Legacy of the Phoenicians, Celts, and Other Forgotten Explorers, Bear & Company, Rochester, Vermont, 2015, p.209.

2. Kuppuram, G., India Through the Ages, pp 65..527-31.

3. Ibid., pp.527-31.

4. Thompson, Gunnar, American Discovery: Our Multicultural Heritage, Hayriver Press, Colfax, Wisconsin, 2012, p.216.

5. Rao, S. R., Shipping in Ancient India, in India’s Contribution to World Thought and Culture, Published by Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan, Chennai, 1970, p. 83.

6. Science and Technology in Ancient India, by Editorial Board of Vijnan Bharati, Mumbai, August, 2002, p. 105.

7. Ibid., pp. 108-09.

8. Ramachandran, K. S., Ancient Indian Maritime Adventures, in India’s Contribution to World Thought and Culture, Published by Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan, Chennai, 1970, p. 74.

9. Soni, Suresh, India’s Glorious Scientific Tradition, Ocean Books Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, 2010, p. 68.

10. Ibid., p. 72.

11. Ibid., p. 73.

12. Shah, Niranjan, Little Known Facts About Shipping Activity in Ancient India, in India Tribune, January 8, 2006.

13. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 1) (Singhal, D. P., Red Indians or Asiomericans–Indian Settlers in Middle and South America, India’s Contribution to World Thought and Culture, Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan Trust, Chennai, India 1970, p.644.

14. Thompson, Gunnar, American Discovery: Our Multicultural Heritage, Hayriver Press, Colfax, Wisconsin, 2012, p.223.

15. Thompson, Gunnar, American Discovery: Our Multicultural Heritage, Hayriver Press, Colfax, Wisconsin, 2012, p.235.

Leave a Reply