Ancient and mediaeval Indian kingdoms relied heavily on active commerce, both domestic and international. Indian economy has come full circle, after a long period of colonial suppression followed by oppressive socialist policies post-Independence, rediscovering its identity as a capitalist economy built on the industriousness and innovation of small producers and merchants.

Dharma, Dhanda, Digital: Examining the Suppression of India’s Commercial Ethos Through the Ages

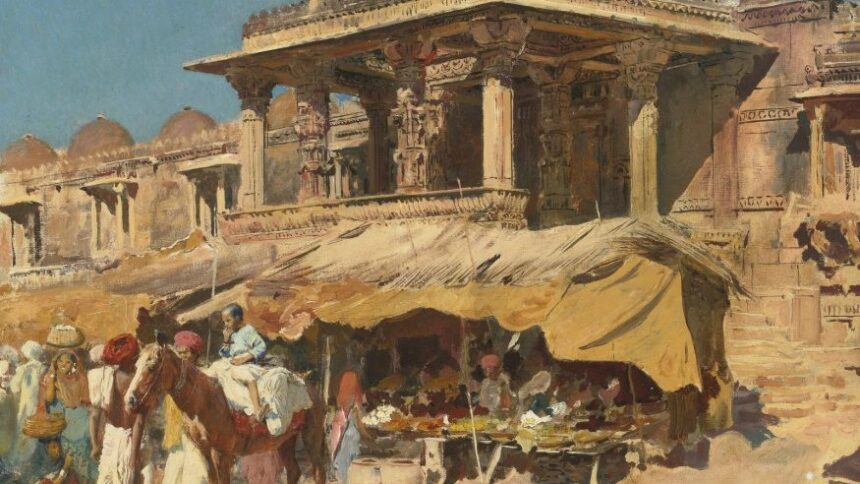

India has a long and rich history of trade and commerce, with mercantile activity being a core part of the country’s economic and cultural fabric for millennia.

Archaeological evidence from sites like Lothal, Surkotada, and Dholavira indicates that the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 3000 BCE – c. 1500 BCE) engaged extensively in trade both within the subcontinent and internationally, with artefacts showing links to Mesopotamia. The Vedas and other ancient Hindu scriptures also provide ample references to merchant classes and their enterprises. For instance, the Rig Veda (c. 1500 BCE – c. 500 BCE) refers to tradesmen and artisans such as carpenters, metalworkers, and weavers (Rig Veda 10.72). The Arthashastra, authored by Chanakya (c. 3rd century BCE), provides detailed prescriptions on organising trade, commerce, markets, taxation, and management of state resources.

व्यापारं परिचरेत् स्वधर्मेण न परधर्मेण |

Vyāpāraṁ paricareta svadharmeṇa na paradharmeṇa

“One should conduct business by following one’s own duty, and not the duty of others.” (Arthashastra 1.13.5)

This excerpt underscores the deep-rooted ethos of trade as a noble pursuit in itself, in contrast to exploitative systems where trading was viewed as immoral. Ancient and mediaeval Indian kingdoms relied heavily on active commerce, both domestic and international. Major ports and trading hubs like Broach, Cambay, Muziris, Arikamedu, Mamallapuram, and others along the coastlines indicate the vibrant maritime trade networks that had developed by the 1st millennium CE. Merchant associations like the Manigramam, Anjuvannam, and Ainnurruvar handled much of the overseas trade with Southeast Asia, China, Arabia, and Europe. Agricultural surpluses as well as handicraft goods were exchanged for gold and spices. Guild systems, banking infrastructure like hundis, and royal patronage of merchants point to a sophisticated commercial ecosystem. Religions like Buddhism and Jainism that originated around the 6th century BCE emphasised the virtues of commercial activity.

However, the establishment of the English East India Company in 1600 CE marked a major shift, as colonial forces systematically suppressed indigenous capitalist systems. From its origins as a monopoly trading body, the East India Company (EIC) morphed into a violent corporatist entity that ran the country as a totalitarian regime focused on extracting wealth rather than generating it. The EIC quashed competition from local traders through unethical means, even resorting to physical force when required.

Scholar David Washbrook notes how the Company undermined existing production systems by remoulding them to serve imperial needs:

“The East India Company set about systematically destroying India’s textile export industry, carting off the machinery to Britain, imposing duties and tariffs of up to 70%, and flooding the country with subsidised Lancashire textiles which were vastly inferior but cheaper.”

Princely states began emulating such extractive economics as the model to aspire towards. These trends garnered much hatred and resentment among the Indian populace at large. So when India gained independence in 1947, it swung to the other extreme by adopting socialist policies that stifled free enterprise even further. The goal was to prevent foreign interests from again capturing the economy, but the effect was excessive state control that choked off growth.

Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, said in 1956:

“The public sector has to assume a predominant and direct responsibility for industrial and economic progress…the only justification for private enterprise in India was the actual development of the economy.”

This exemplifies the mindset that vilified capitalism and individual commercial freedom. The next few decades saw the rise of the License Raj, where the state decided what could be produced, by whom, and how much. Permits and approvals were required for any economic activity, creating a corrupt bureaucratic setup. Indira Gandhi nationalised major industries like banking, mining, telecom and textiles, taking away spectrum and resources from private players. While some Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) like the State Bank of India and Oil and Natural Gas Corporation performed decently, most became hotbeds of inefficiency and graft.

Business came to be regarded as almost criminal, given the difficulties in navigating the obstructive government systems. Only large crony capitalists thrived by aligning with political interests, while small traders resorted to the black market. India’s share of global GDP fell from over 25% in the 1700s to around 3% by the time economic liberalisation began in 1991. Clearly, suppressing entrepreneurial forces and vilifying profit seeking had disastrous consequences.

It was the reformative policies of leaders like P.V. Narasimha Rao, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh that enabled the shackles on private enterprise to be loosened, although gradually. However, the public discourse continued to harbour some distrust of profit-seeking activities. It is only recently that the entrepreneurial spirit has made a real comeback, energised by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s campaigns like Startup India, Standup India and Make in India. Besides policy changes to enable startups and MSMEs, he has consistently highlighted the virtues of small traders and businessmen. His humble beginnings as a chaiwala who rose to lead the nation also inspire many to chart their own entrepreneurial journey. The number of new business registrations, unicorn startups, and MSMEs show clear trends:

- India added 1.24 million new MSMEs in FY 21, a 95% increase over FY 20.

- 44 Indian startups achieved unicorn status (valuation of $1Bn+) in 2021, more than the previous 11 years combined.

- India’s startup ecosystem is the 3rd largest globally, with over 61K DPIIT-recognized startups.

I believe India is now embracing its identity as a capitalist economy, but in its own unique mould that prioritises inclusive growth. The jugaad mindset produces frugal innovation through constraint-based problem solving. Familiarity with scarcity makes Indian entrepreneurs adept at creating affordable, scalable solutions. The vast domestic market enables startups to refine products before going global. India’s strength also lies in small businesses, with MSMEs contributing 30% to GDP and 45% to exports while creating millions of jobs. With digitization initiatives like UPI and Jan Dhan-Aadhaar-Mobile (JAM), even micro-merchants in rural areas can avail formal credit and modern payment mechanisms. Women are also entering entrepreneurship in record numbers, empowered by government schemes like MUDRA loans. I hope that India continues on this upward trajectory to become a leading startup nation and MSME capital of the world, while retaining its ethos of compassionate capitalism. By nurturing its innate spirit of enterprise, India can deliver equitable growth, opportunities and prosperity for all.

To conclude, India has come full circle, rediscovering its identity as a capitalist economy built on the industriousness and innovation of small producers and merchants. But this time, it must ensure that the excesses of unchecked greed that led to its subjugation in the colonial era are kept in check through inclusive policies, safety nets and affirmative action. India’s suppressed capitalist soul has finally broken free of its shackles. Its future looks more vibrant than ever.

References:

- Washbrook, D. (2015). The Commercialization of Textiles in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century India: A Reply to Rudner. The Journal of Economic History, 75(4), 1179-1192.

- Kangle R.P. (Trans.) (2000). The Kautilya Arthasastra, Part II. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

- Nehru, J. (1956). Speech to the Congress Party Plenary Session. Retrieved from http://www.nehrumemorial.nic.in

- Ministry of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises. (2021). Annual Report 2020-21. Government of India.

- (2022). India Tech Start-up Ecosystem – 2021 YTD Performance Report.

Leave a Reply