Dr Pingali Gopal reviews Essence of the Fifth Veda, a captivating compendium by Gaurang Damani.

Book review: Essence of the Fifth Veda by Gaurang Damani

Essence of the Fifth Veda. Gaurang Damani. Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House. 2021. Pages 245. Rs 350.

Introduction

Gaurang Damani is an electronics engineer, an entrepreneur, a social activist, and a vocal Dharmic all rolled into one and is presently based in Mumbai. He has written this wonderful book, which is a compendium of many stories from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Puranas, and Bhagavatam. He also manages to squeeze out the essential philosophy of arguably the most profound text of Sanatana Dharma—The Yoga Vasishta. The easy-to-read and well-organized book is both informative and entertaining. A trained scholar would find the book entertaining; an Indian who grew up with these stories would find the book distilling his or her own understanding; and a non-Indian, completely unfamiliar with Indian culture, would simply marvel at the incredible range of stories in our culture.

The Puranas and the Itihasas (Ramayana and Mahabharata) are known as the Fifth Vedas. The Vedas were at a scholarly level, perhaps beyond the average person’s comprehension. It was the brilliance of our seers who wrote the Puranas and Itihasas for the common public as equal ways of understanding dharma and attaining liberation. In this regard, they were accessible and valid for all, irrespective of language, varna, jati, or region. In terms of their knowledge claims, explication of dharma, and in helping an individual on the path to liberation, they stand on an equal footing with the four classical Vedas.

The stories in Damani’s book from our Itihasas and Puranas come at a rapid pace, and each short chapter caters well to the current generation of brief attention spans. This book might also stimulate many to get back to book-reading and explore our classics further. There are many questions for an Indian growing up in the cultural milieu of these stories, either through grandparents’ tales (becoming rarer these days), school books, popular storybooks, comics, or movies: Why did Sita undergo the Agni-Pariksha? Was the killing of Vali by Rama just? Was Ravana a bad person all through, or was it simply a one-off behaviour with regards to Sita? Do the places mentioned in the epics really exist, and do they have a connection with present-day geographical locations? Who were the 16,108 wives of Krishna? Were the described people real people or were they the fervent imaginations of brilliant poets? The book answers many such questions, often lurking in the back of our minds but not affecting our deep respect towards them. These stories from Puranas and Itihasas are in the thousands. We do not realise how important a role they play in our lives, and this essay will hopefully clarify some issues raised by this unusual and interesting book.

A Background: Vedas, Vedangas, Puranas, And Itihaasas

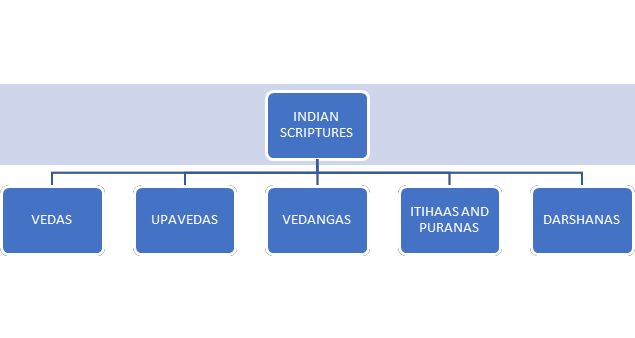

The five groups of texts—Vedas, Upavedas, Vedangas, Purana-Itihasas, and Darsanas (philosophies)—lay the foundation for the knowledge and wisdom of our heritage and cover the laukika (worldly) and the alaukika (transcendental) realms of knowledge. The primary texts, the commentaries, and the commentaries on the commentaries run into the thousands. The huge corpus of Hindu scriptures is divided broadly into the srutis (that which is heard) and smrtis (that which is remembered). Sruti refers to the four Vedas: Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda, and Atharvaveda. The Sruti is apauruṣeya, or unauthored, in this sense; they are eternal truths. Smriti (that remembered) is the strengthening of what lies in reality through the authorship of different sages across time. Hence, as Vedic traditions claim, Sruti and Smriti form one inseparable body of knowledge in the truths conveyed; their natures differ only with respect to authorship.

The Smritis constitute texts studied along with the Vedas: Vedangas, Darshanas, and Purana-Itihaasas.

The Puranas consist of stories to educate ordinary people on many topics, like famous people, rituals, pilgrimages, festivals, arts, sciences, and so on. They deal with geography, local traditions, history, and folklore with great spiritual insight. There are eighteen Mahapuranas and eighteen Upa-puranas. The Purana literature also includes Sthalapuranas pertaining to local folklore and royal lineages, mixing with the traditional stories of the Puranas. The Itihasas are the famous epics of India—the Ramayana of Valmiki and the Mahabharata of Vyasa. These literally mean “thus it happened,” but they are also stories with metaphysical, allegorical, and philosophical insights aimed at individual liberation. The spirit of the Upanishadic wisdom and the four purposes of life (kama, artha, dharma, and moksha), especially dharma and moksha, run throughout the two most important Itihasas.

Histories, Itihasas, Myths, and Stories

Secular historians, standing against the “religiosity” of the masses, taught us that our stories were merely disguised historiographies, poetic exaggerations, or lies by our ancestors. A typical Indian would say, “Rama and Krishna may or may not have existed, but the Ramayana or Mahabharata are always true.” This is an attitude of Indians when dealing with their legends and stories, which fundamentally is beyond the comprehension of western traditions and the modern Indian intellectual. In the western intellectual tradition, myths are simply false and facts are true. Only what is “true” serves as the foundation for all logic, reason, and science.

However, we clearly learn in our growing years that our stories and epics (Itihasas) are different from what we learn at school in history, geography, and science lessons. Converting Itihasa into history would destroy our past as the remembered past of a thriving and rich culture. Historical chronologies were well-documented; it was not that Indians lacked proper historical consciousness, a common allegation by western scholars.

The British, heirs to Enlightenment philosophers who scrutinised Roman and Greek epics for logic, coherence, and truth value, failed to understand that the stories were not true or false doctrines, and were not descriptions of the world. They understood these “mythologies” as simply superstitious expressions of primitive fears. Unfortunately, as a reaction to the “secular and scientific” narratives, a reaction came forth from certain more aggressive Hindu elements, who claimed that stories about the past are literally our histories. Ultimately, because of a poor understanding of what stories mean to Indian culture from both “rational” and “nationalistic” perspectives, a threat looms large over Indian culture.

The Importance of Stories In Indian Culture

Dr SN Balagangadhara Rao, the eminent philosopher explains in detail in his writings what stories mean to us in Indian culture and how they form a foundation of our socialising process and learning of moral values through a process called mimesis. He explains also how our itihasas differ from histories. A wrong understanding of Indian stories by western intellectuals and their faithful Indian followers has caused immense intellectual violence to our culture.

Stories play an extremely crucial role in the socialising process while growing up in Indian culture. In western culture, stories may entertain and form a genre of literature, but they do not instruct. Indians never realise the influence and importance of the incredible stock of stories present in our culture, where there is a story available for every conceivable situation. How do stories and legends function as units in a learning process? They work both as theoretical models representing small parts of the world and as practical exemplars that one can emulate. Stories are thus a combination of the “theoretical” and the “practical” simultaneously.

Stories and legends, whether true or false, preserve a sense of existing order in culture and the cosmos without specifying what that order is. Second, without any explicit morals or methods of practical action, these stories (exemplars) can teach through the specific Indian cultural way of learning—mimetic learning. This learning through exemplars creates new and original actions from old ones, just as new ideas are generated from old ones. The exemplars, or stories, are generative of new actions in different contexts. Thus, if we look at stories in India, they enable one to execute an action in a specific situation, taking an example of an action in a completely different context. This is in severe contrast to the western culture, where there are certain context-free moral principles to imbibe and apply for the rest of one’s life. This common method of learning Indian culture through mimesis and stories has many intriguing consequences, the most intriguing is that educational authorities do not have to be coextensive with religious, moral, political, or divine authorities.

Mahabharata And Ramayana: Defining Bharatvarsha- A Cultural Civilization

India, or Bharata, has been an ancient “felt community” (à la Saumya Dey) for thousands of years because it has not emerged through deliberate cultural or linguistic systematization. Thus, people could belong to the same land as well as the same set of meanings, forming a great unity even with different languages. Such “felt communities” differ from the notion of “nations” in their fundamental non-predatory nature. India, or Bharat, has never expanded outside its boundaries for the forcible stamping out of cultures and establishing itself politically. Our epics and literature are clear evidence of the geographical, cultural, and civilizational unity of Bharatvarsha. For example, in the Vishnu Purana, Bharata is the “land north of the ocean and south of the snowy mountains, or the Himalayas.” The Ramayana and Mahabharata have played the most important roles in defining and integrating our country as a civilizational entity called Bharatvarsha. The epics leave no doubt about a sacred geographical unity and a cultural bond across an incredible diversity of languages, sub-cultures, and traditions.

Yoga Vasistha

Damani does well to include the essence of Yoga Vasishta in the book. The Yoga-Vasistha, over 29,000 verses long, has an unknown date, but scholars consider it most likely an addition to the Ramayana, much later than the original. The book discusses the nature of consciousness, mind, matter, space, and time. Yoga-Vasishta is primarily a text for individual liberation, but the amazing facet of the book is its expositions and speculations on many aspects of physics and nature. It talks about parallel universes (now a contemporary thought emerging from the latest, but controversial, string theory), space travel, the evolution of Earth, and so on. The breath-taking philosophy, based on Advaita, or non-dual philosophy, stays relevant across time and space. It is the most unfortunate legacy of a warped education policy over decades that most Indians are completely unaware of Indian philosophies, especially the Yoga Vasishta.

Concluding Remarks

The author, in the selection of stories from our vast civilisational library, brings forth all the above aspects of Indian culture with great clarity. It adequately demonstrates why India is a civilizational entity. The book also shows how the incredible range and variety of stories in Indian culture play a crucial role in our socialising process without even realising it. The stories in our culture form the basis of our ethics and values, which in turn create a harmonious society. For Indian knowledge systems, fulfilment of all the four purusharthas was important: artha, kama, dharma, and moksha. These broadly translate into money, desires, code of conduct, and liberation, respectively. Each text catered to a specific aspect of human activity, but the underlying framework of most texts remained dharma even as the final goal in Indian culture was moksha.

In this short book with extensive references, Gaurang Damani highlights the importance of our Pauranic and Itihasa stories. Understanding Dharma is the overriding concern in our texts and is the same here too. He wonderfully maps the present geographical locations in India to the places mentioned in the Ramayana, Bhagavatam, and Mahabharata. Are they true or false? Who knows? True or false, they are interesting. Travelling across India, we find one place where Sita washed her Sari, another place where the Pandavas rested, and yet another where the Pandavas built a temple. It is the essence of Indian culture that one prays inside the Kedarnath temple, truly believing that the Pandavas built this temple (during their final journey) but stays intact as a “rational”, “logical”, and “coherent” being (scientist, engineer, doctor, journalist, anything) without ambiguity.

The message for the readers: buy the book! For the author, yeh dil maange more (this heart wants more)!

Leave a Reply