An ignorance of sacred texts along with a loose argument has made the ban on Paśubali, an attack on Tantric worship.

Ban on Paśubali – A Judicial Blunder (Part 2)

This is the second part of an essay critiquing the recent ban on Paśubali by the Tripurā High Court. The first part link pointed out the numerous basic flaws in the judgement. In this part, I shall further analyse the fallacies in it and thereafter, establish the essential nature of Paśubali in Śākta tantra and related branches of Sanātana Dharma.

A fallacious judgement

1. The crux of the judgement – Let us try to understand how the judges confidently concluded on something whose significance they didn’t even care to understand. The answer lies in a common assumption — “God must be ‘good’ and a good God must not need violent animal sacrifice. So this practice must be a superstition.” The judgement reads like a ‘Constitutional dress’ for this assumption. As a personal belief, such an assumption might be harmless but when it is imposed upon others with a veneer of authoritative morality, it is certainly dangerous. So let me challenge the authoritative morality that accompanies this personal belief.

2. ‘God’ in Abrahamic and Dhārmika traditions – That ‘God is good’ or that ‘God must be good’ is a classic Christian idea of God, the loving father in heaven. In the Dhārmika traditions, ‘God’ is a more nuanced entity and maybe ‘good’ as well as ‘bad’, as and when the situation demands. This is so because the purpose of ‘God’ is different in these traditions. In the Abrahamic traditions, God is there to guide towards the attainment of Paradise, a blessed place full of pleasures and without sorrows. But in the Dhārmika traditions, ‘God’ is there to guide us towards mukti, a state beyond all dualities of pleasure-pain, happiness-sorrow, etc. This is a fundamental difference between the two traditions and this arises because the final aim of the Abrahamic is to be good whereas that of the Dhārmika is to move beyond good and evil.

Sometimes, it so happens that people get identified with a certain notion of goodness and this becomes detrimental to their societal and spiritual growth. A classic example of such a person is Arjuna, lamenting and wailing in Arjuna Viṣāda Yoga of the Śrīmad Bhagavad Gītā. Arjuna’s position exudes a veneer of authoritative morality. He asks, ‘How can killing my own brethren lead to any good? How can I commit such a heinous and immoral act?’ His position would seem to be the morally correct one to many people, but as the Bhagavad Gītā unfolds, we see the moha inherent in such a position. The problem with moha is that very often, it presents itself as a paragon of justice and morality. During such situations, Bhagavāna has to ‘play bad’ and strike at moha so that the truth is revealed. Though painful, this moves us closer to mukti.

Given that the courts claim themselves to be secular, it is, therefore, expected that the judges would stop projecting their personal ideas of goodness upon God and let the śāstras decide the nature of ‘God’ in the Dhārmika traditions.

Another casual observation made by the judges is that Paśubali is a violent and abhorrent practice. Let us look at this allegation carefully.

3. Is Paśubali hiṃsā? – An act can be called violent if the subject was propelled by violence to commit the act. We call a robbery a violent act since the robbers are propelled by violence to rob people. But we don’t call the killing of terrorists a violent act since the army personnel were not propelled by violence (but by a sense of duty) to kill them. Similarly, we don’t call the death sentencing of criminals a violent act since the judge was not propelled by violence (but by a commitment to justice) to kill them. In the same vein, paśubali is not a violent act since the sacrificer is not propelled by violence (but by a sense of sacrifice) to kill the animal. Hence Paśubali is ahiṃsā (non-violent). The śāstras unequivocally support this statement. The Devī-Bhāgavat MahāPurāṇa says,

अहिंसां च तथा विद्धि वेदोक्तां मुनिसत्तम।

रागिणां सापि हिंसैव निःस्पृहाणां न सा मता। प्रथम स्कन्ध,अष्टादश अध्याय,श्लोक ५९

The killing of animals in sacrificial ceremonies is ahiṃsā whereas killing of animals out of selfish attachments is hiṃsā.

अहिंसा परमो धर्मो विप्राणां नात्र संशयः।

दया सर्वत्र कर्तव्या ब्राह्मणेन विजानता।

यज्ञादन्यत्र विप्रेन्द्र न हिंसा याज्ञिकी मता। द्वितीय स्कन्ध,एकादश अध्याय,श्लोक ३९

There is no doubt that ahiṃsā is the greatest of all dharma. The brāhmaṇa should show daya everywhere and should not kill animals other than during sacrifice. Killing animals during a sacrifice is not hiṃsā.

Hence the claim that Paśubali is a violent act does not stand either on first principles or on śāstrika evidence. With this, we find that the crux of the judgement is completely hollow, standing solely upon personal beliefs and assumptions fallaciously generalised with a veneer of authoritative morality.

Now we focus on another fallacious assumption in the judgement. The judges, without any expertise on the subject whatsoever, declare that Paśubali is not an integral part of Śākta worship. We prove the fallacy inherent in this position by showing the essential nature of Paśubali in Śākta tantra and related branches. For this, we use Śāstrika evidence from the two main Śākta Purāṇas, the Devībhāgavat MahāPurāṇa and the Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa. We also draw from Tāntrika texts like YoginīTantra and MahāNirvāṇaTantra. It is noteworthy that, by the judges’ own admission, the judgement completely falls apart if Paśubali is an integral part of Śākta worship.

Essential nature of Paśubali in Śākta tantra

1. Paśubali in Devībhāgavat MahāPurāṇa – The Devībhāgavat MahāPurāṇa is one of the most revered and authoritative texts of the Śākta Sampradāya. It describes the līlā of the Devī, the stories of Her devotees, the methods of Her worship. Therefore, this is a primary resource in deciding whether Paśubali is an integral part of Śākta worship.

Now, who, among the authorities, is the best in deciding how to worship the Devī? Undoubtedly, the Devī Herself. In the Devībhāgavata MahāPurāṇa, the Devī clearly says,

अष्टम्यां च चतुर्दश्यां नवम्यां च विशेषतः।

मम पूजा प्रकर्तव्या बलिदानविधानतः। तृतीय स्कन्ध, चतुर्विंश अध्याय, श्लोक १८

Especially during Aṣṭamī, Caturdaśī and Navamī, worship me with Bali.

When the Devī Herself says that Bali is required for Her worship, there should be no further doubt about the essential nature of Bali in Śākta Tantra. But still, let us also look at what the sages said about the methods of worshipping Devī. When Śrī Rāma was sorrowfully reminiscing about Jānakī, Nārada told him to worship Devī to kill Rāvaṇa. Describing the procedure, the sage says,

मेध्यैश्च पशुभिर्देव्या बलिं दत्त्वा विशंसितैः।

दशाशं दवनं कृत्वा सशंकस्त्वं भविष्यसि। तृतीय स्कन्ध, त्रिंश अध्याय, श्लोक २०

O Rāma, you should offer the sacrifice of a sacred animal before the Devī.. With this, you shall surely release Jānakī.

Śrī Rāma follows Nārada’s advice and offers Bali before the Devī, as we find in,

उपवासपरो रामः कृतवान्व्रतमुत्तमम्।

होमं च विधिवत्तत्र बलिदानं च पूजनम् । तृतीय स्कन्ध, त्रिंश अध्याय, श्लोक ४३

So we see that Śrī Rāma sacrificed a sacred animal before the Devī to kill Rāvaṇa and release Jānakī. This should remove all doubts about the antiquity of the practice.

At this point, a critic may say that even from a religious perspective, this practice is biased against the animals because the sacrificers get their desires fulfilled while the sacrificed animals get nothing. We respond by pointing out that from a Dhārmika perspective, a sacrifice is beneficial to both the sacrificer and the sacrificed. The sacrificers get their wishes fulfilled and the sacrificed attains the highest heavens. So all the śāstras unanimously proclaim that paśubali before the devas is ahiṃsā.

देव्यग्रे निहता यांति पशवः स्वर्गमव्ययम्।

न हिंसा पशुजा तत्र निघ्नतां तत्कृतेऽनघ |

अहिंसा याज्ञिकी प्रोत्का सर्वशास्त्रविनिर्णये ।

देवतार्थ विसृष्टानां पशूनां स्वर्गतिर्ध्रुवा । तृतीय स्कन्ध, षड़्विंश अध्याय, श्लोक ३३, ३४

In fact, since killing otherwise is hiṃsā, people who eat meat are asked to sacrifice the animals before eating their meat.

मांसाशनं ये कुर्वन्ति तैः कार्य पशुहिंसनम् ।

महिषाजवराहाणां बलिदानं बिशिष्यते । तृतीय स्कन्ध, षड़्विंश अध्याय, श्लोक ३२

The above śloka also points out which animals should be especially considered for sacrifice:- buffalo, goat, boar. Indeed, in the temples of Tripurā, mostly goats and sometimes buffaloes are sacrificed. So we see that this is not a ‘superstitious practice’ as the judges would like us to believe, but has sound backing in the revered texts of Sanātana Dharma. If there is further doubt, let me quote what Dharmarāja Yama says about how to worship the Devī,

शारदीयां महापूजां प्रकृतेर्यः करोति च।

महिषेश्छागलैर्मेषैः खड़्गैर्भेकादिभिः सति।

नैवेद्यैरूपहारैश्च धूपदीपादिभिस्तथा।

नृत्यगीतादिभिवद्यिननिकौतुकमंगलम्।

शिवलोके वसेत्सोऽपि सप्तमन्वन्तरवधि।

पुनः सुयोनिं संप्राप्य नरो बुद्धिं च निर्मलम् । नवम स्कन्ध, त्रिंश अध्याय, श्लोक ७८,७९,८०

One who performs Śāradīya Mahāpūjā with the sacrifice of buffalo, goat, sheep, etc along with naivedya, upahāra, dhupa, dīpa, nṛtya, gīta, kautuka, etc resides in Śivaloka for seven manvantaras and thereafter, is born in a good family.

From Dharmarāja let us go to Śrī Nārāyaṇa to further learn how to worship the Devī.

पञ्चम्यां मनसां ध्यानम् देव्यै दद्याच्च यो बलिम्।

धनवान्पुत्रवांश्चैव कीर्तिमान्स भवेद्ध्रुवम्। नवम स्कन्ध, अष्टचत्वारिंशो अध्याय, श्लोक ९

One who worships the Devī with Bali on Pañcamī becomes wealthy and famous.

This should convince the reader of the essential nature of Paśubali in the worship of the Devī. Let us now look at another Purāṇa that describes the methods of worshipping Devī, the Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa.

2. Paśubali in Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa – The Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa is a popular Śākta Purāṇa. The Durgā Saptaśatī, also called Śrī Śrī Caṇḍī, widely recited throughout Bhārata to propitiate the Devī, is taken from this Purāṇa. In this Purāṇa too, the Devī clearly states that Paśubali is an inseparable part of Her worship.

बलिप्रदाने पूजायामग्निकार्ये महोत्सवे।

सर्वं ममैतच्चारितमुच्चार्यं श्राव्यमेव च। दुर्गा सप्तशती, द्वादश अध्याय, श्लोक १०

जानताजानता वापि बलिपूजां तथा कृताम्।

प्रतीच्छिष्याम्यहं प्रीत्या वह्निहोमं तथा कृतम्। श्लोक ११

सर्वं ममैतन्माहात्म्यं मम सन्निधिकारकम्।

पशुपुष्पार्घ्यधुपैश्च गन्धदीपैस्तथोत्तमैः । श्लोक २०

Medhā ṛṣi, an expert on the methods of Śākta worship, too says that one should worship the Devī with Paśubali.

रुधिराक्तेन बलिना मांसेन सुरया नृप।

प्रणामाचमनीयेन चन्दनेन सुगन्धिना। वैकृतिक रहस्य, श्लोक २८

So we see that both the Śākta Purāṇa clearly state that one should worship the Devī with Paśubali. Now we shall look at some Tāntrika texts to learn more about the significance of Paśubali.

3. Paśubali in Tantra – We consider two revered Tāntrika texts — Yoginī Tantra and MahāNirvāṇa Tantra. Dedicated to Kālī and Kāmākṣyā, Yoginī Tantra describes many secret Tāntrika practices. And the MahāNirvāṇa Tantra discusses the philosophical and practical aspects of Tantra along with the corresponding mantras. Both these texts categorically urge the Tāntrika practitioner to offer Paśubali before the Devī. They also specify which animals should be sacrificed and how they should be sacrificed.

नापेक्षा जायते कान्ते चावश्य फलभागभवेत।

महाप्रयागे देवेशि कृष्ञच्छागं बलिं हवेत्।

पूजान्ते सततं देवि तन्मांसैर्व्वह्निमर्च्चयेत्।

विधिः सर्व्वत्र कथितोदीव्यवीर पशुक्रमात् । योगिनी तन्त्र, चतुर्थ पटल, श्लोक २३,२४

यथेष्टमनसाराध्यं अष्टासु च बलिं हवेत्।

काल्यादिभ्यो महेशानि पूजयित्ना विधानतः। योगिनी तन्त्र, पञ्चम पटल, श्लोक २२

सर्वोपचारैः संपूज्य बलिं दद्यात् समाहितः। महानिर्वाण तन्त्र, षष्ठ उल्लास, श्लोकार्ध १०४

आद्यापूजोक्तविधिना बलिहोमं प्रयोजयेत।

कौलार्च्चनं दक्षिणाञ्च कृत्वा कर्म समापयेत्। महानिर्वाण तन्त्र, दशम उल्लास, श्लोक १०२

Paśubali is ubiquitously present in Tāntrika texts. The texts also discuss the metaphorical significance of this practice. The paśu represents the pāśa (like bhaya, ghṛṇā, etc) or the bondages of the jīvātmā, the Khadga represents jñāna. The pāśa is struck down by jñāna and the citta-rūpa māṃsa is offered to the Paramātmā. Thus paśubali is a microcosmic representation of mukti of the jīvātmā and its merging in the Paramātmā.

Here, another thing needs to be pointed out. The judges, based on flimsy evidence of a distant second-hand account of a British official, declare that previously large scale human sacrifices that took place in Tripurā were banned and as such, now animal sacrifices should be banned. But the tāntrika texts clearly state that one should not sacrifice humans or human-like animals.

नरमांसं न भुञ्जीयात् नराकृतिपशुंस्तथा।

वहुपकारकान् गाश्च मांसादान् रसवर्जितान्। महानिर्वाण तन्त्र, अष्टम उल्लास, श्लोक १०८

So the story of ‘large-scale human sacrifices’ seems more like a myth concocted by officials of the imperial era.

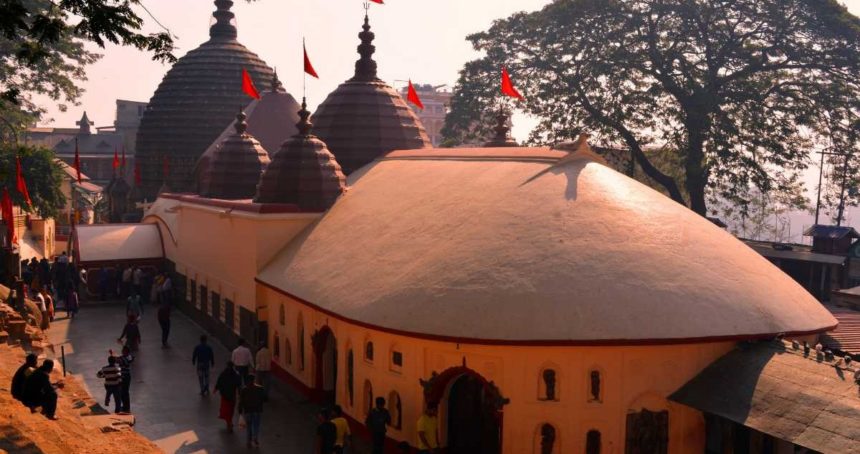

4. Paśubali in Tripurā – Now we look at the history of Paśubali in Tripurā. The most authoritative text on the history and customs of Tripurā is Rājamālā. It is a portrait of medieval and modern Tripurā, describing the lineage of the kings and the socio-cultural customs of the land. According to Rājamālā, Paśubali has been practised in Tripurā since time immemorial. The inhabitants of this land, the Kirāta tribe were worshippers of Śiva. They worshipped Him with paśubali.

কিরাতের মতে সবে পূজা আরম্ভিয়া ।

বলিদান কৈল বহু ছাগ আদি দিয়া ॥ রাজমালা, ত্রিপুর খণ্ড

They worshipped Śiva according to the Kirāta traditions and sacrificed many goats, etc.

The main temple of the royal family of Tripurā is the Caturdaśa Devatā Mandir. (It is noteworthy that the petitioner had asked the court to ban paśubali in this temple.) Legend says that Śiva Himself asked the Kirāta people to set up this temple and worship with Paśubali.

ত্রিলোচন রাজাকে লইয়া তোমা সবে ।

পূজিবা নানান দ্রব্য বলি উপলাভে ॥ রাজমালা, ত্রিপুর খণ্ড

All of you along with King Trilocana, worship with many dravya and Bali.

And the people followed His words.

আষাঢ় মাসের শুক্লা অষ্টমী তিথিতে ।

আনিল নানান দ্রব্য পূজাবিধিমতে ॥

মহিষ, গবয়, ছাগ দিল লক্ষ বলি ।

কিরাতে আনিয়া দিছে এসব সকলি ॥ রাজমালা, ত্রিলোচন খণ্ড

In the Śuklā Aṣṭamī tithi of Āṣāḍha māsa, they worshipped with bali of buffaloes, goats, etc.

The tradition of worshipping the Caturdaśa Devatā with great fanfare during this time of the year has continued till this day. This seven-day long festival is known as Khārcī Pūjā. The Rājamālā describes in detail the ritual of paśubali during Khārcī Pūjā.

ত্রিপুর রাজাতে কহে চন্তাই সাবধানে ।

তিন বলি নৃপতিয়ে স্বহস্তে ছেদিব ।

তিন দেবতা ভিন্ন রুধিরে তার্পব ॥

অন্য যত বলি সব মণ্ডপ বাহিরে ।

চন্তাই দিব ধারা দেওড়াই ছেদ করে ॥ রাজমালা, ত্রিলোচন খণ্ড

The cantāi (purohita) carefully told the King that the latter should offer three Bali before the three devatā and the rest of the Bali should take place outside the maṇḍapa. The deoḍāi should do the chedana and the cantāi would provide the water.

And this is how it has been, since time immemorial to this day. I have seen it in person many times. But today, this half-a-millennium-old practice faces the myopic judgement of people who never cared to understand its significance.

Conclusion

So we see that all the primary sources, be it the Purāṇa or the Tāntrika texts or the historical documents, unanimously state that Paśubali is an integral part of Śākta tantra and related branches and has been practised since time immemorial. The fact of the matter is that Paśubali was not only approved by the society in general but also aspired for by the common people. Other than being a ritual for the fulfilment of desires, the sacrifice had an added advantage. It brought people face to face with death. It reminded them of their own mortality. It reminded them that one day like these animals, they too have to die. But there is an option. Like the animals, their death too can be a sacrifice and through sacrifice, they can transcend death and become immortal.

Indeed only through sacrifice, we become deathless. When we sacrifice our lives for our devas, we become aligned with them. As such, we live forever in them because the devas are immortal. Today, when we are becoming more and more self-centred with scepticism and narcissism all around us, Paśubali becomes all the more relevant because it brightly kindles in our hearts the fire of sacrifice. Without sacrifice, life itself is meaningless. Indeed, everything great that was ever achieved is the result of a proportionate sacrifice. Let us not ban a tradition that celebrates sacrifice.

Leave a Reply