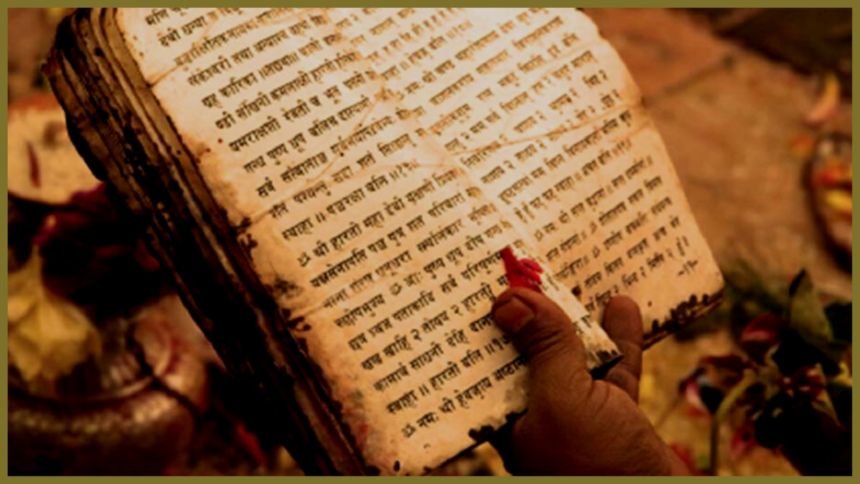

Exploring the idea of apaurusheyatva of the Vedas.

APAURUSHEYATVA OF THE VEDAS- Part 4

Disclaimer: This piece by Dr. Pingali Gopal is with permission from Chittaranjan Naik. The article is a summary of a five-part article written by Chittaranjan Naik on an online forum for discussing Advaita. The ideas and the themes solely belong to the latter. Dr. Pingali Gopal claims no expertise or primary scholarship in the subject matter. The purpose of the article is to hopefully stimulate the readers to explore further. One can access the full article here:

APAURUSHEYATVA OF THE VEDAS BY CHITTARANJAN NAIK

**********************************************************************

Continued from Part 3

THE PURVA MIMAMSA PROOF

Foreword To The Purva Mimamsa Doctrine Of Words

Purva Mimamsa is perhaps one of the most abstruse to understand. It is a philosophy that speaks about a supernal region far beyond the realm of the universe, in a realm in which the perfect word and the perfect object lie in absolute silence before they burst upon the stage of the world, clothed with terms ‘existence’ and ‘non-existence’. Mimamsa speaks that illusion does not pertain to words and objects; it pertains to the notion of the eternal word and eternal object as being temporal and ephemeral entities.

In Western philosophy, we would find traces of it in the two philosophies considered the most difficult of all to comprehend – the philosophy of Parmenides of Elea (along with the Eleatic dialogues of Socrates) and the philosophy of Spinoza. Words are mystical things. The science of words is highly esoteric. The Rig Veda says that ordinary people know only the fourth, articulate, stage of speech and that the other three stages lie concealed from them. “Four are the grades of speech, the learned brahmanas know them. Three of them are deposited in secret and indicate no meaning to a common man; for men speak the fourth grade which is phonetically expressed.” (Rig Veda 1.164.45).

The greatest hindrance we face in grasping the unauthoredness of the Vedas is the inability of the mind to form a conception of an unauthored scripture. The pramana called anupalabdhi shows the unauthoredness of Vedas to be the case since authorship would have had the capacity of being perceived and remembered if it should have existed. In order to grasp the eternality of the Vedas one would need to understand the philosophy of Purva Mimamsa. The arguments provided by the Mimasakas to counter the views of the opponents of apaurusheyatva are extensive and many of them are extremely subtle in nature. This is a summary of those arguments.

An Approach To Understanding The Eternality Of Words

The idea that a text can exist only when it has a human author is based on the unexamined idea that the human bodily apparatus is a necessary ground for words to arise. That is, the capacity for words to reside and for speech to arise in a human being is the conscious principle which is a distinct and different entity from the body in which it appears as the individual self or pratyagatman. This conscious principle, which exists in the body as the self is also the Consciousness that pervades the entire universe. As explained in the Vedanta texts, it appears to be in the body only due to an adjunct superimposed on the all-pervading Consciousness. Therefore, words can exist even if there should be no human being present in the universe because the principle in which words reside and from which they arise as speech is the eternally existent Consciousness.

The notion that words exist only when articulated as speech is one of those many unexamined beliefs that persist for a person when he is in samsara. But a critical examination of speech reveals that the knowledge of words and their meanings has to exist a priori for a person to be able to speak those words meaningfully. The knowledge of words that a person has exists in him even when he is sleeping. The knowledge of words existed in the person even during the intermediate period when he was not speaking them; they were then not manifest, that is all.

If we consider the expression ‘knowledge of words’ in respect of a knower, the word ‘knowledge’ refers to the knowledge that the knower has, and the word ‘words’ refers to the object of the knowledge. There cannot be knowledge without there being an object of knowledge. When a person who knows ‘the word rose’ is sleeping, the object of the knowledge that persists in him is the word ‘rose’. Therefore, it follows that words exist as objects of knowledge in a person even when he is sleeping and that words need not be manifest as sound for them to exist.

An analogy may help to illustrate how a word may exist even when not heard (manifest). In a stringed musical instrument, the musical note exists in the string of the veena as the ‘unstruck’ note when it is not sounding and as the ‘struck’ note when it is sounding. Words are similar in nature to this – they remain unstruck when not spoken and they become struck when spoken. The ground for the existence of words is the all-pervading and eternal Consciousness. And these words reside as objects of knowledge in Consciousness even when they are not manifest as articulated speech.

Knowledge, Words And Objects – Traditional Semiotics

A word is that kind of object which is always connected to another object. This is crucial in understanding the apaurusheyatva of the Vedas. The study of the relationships between words and objects is a branch of linguistics known as ‘semiotics’. More specifically, semiotics is the study of signs and of discerning what it is that a sign points to. Unlike in modern linguistics, where there is no certainty or agreement with respect to what it is that constitutes the object of a word, in Indian semiotics the object of the word is the thing itself that exists in the world (or in reality). And unlike in modern sciences and philosophies, in Indian linguistics and Indian traditional philosophies, the world is the world directly perceived.

When a person knows an object, there is always a sign (name) and a signified (object) in the field of consciousness. The Brahadaranyaka Upanishad says that the entire universe is nama-rupa, or name and form. Names and forms lie in Brahman Itself, as the unmanifested and undifferentiated seeds from which manifest names and forms spring onto the stage of creation. The Upanishads emphasize that the relation between names (words) and forms (objects) abides eternally since they exist in the field of consciousness even before manifestation in an undifferentiated state. Thus, there cannot be knowledge of an object without there being a word signifying the object.

It does not matter whether the words are Vedic words or are words adopted by convention; a word necessarily needs to be present as a reference for an object to be known as the referent. One may choose words arbitrarily (small child language or animal language) to represent an object, but the relationship between the sign and the signified is determined by a prior relationship that abides eternally. A word is not merely a set of phonemes because the phonemes do not exist concurrently when spoken and there is nothing to bind them together. And this is one of the key reasons why a word distinguishes from the sound uttered. For the sound to become a word, it needs to have a binding factor that binds it. And that binding factor is the meaning itself.

Therefore, since a word is not a word without the idea (the meaning) binding the phonemes together, the idea (of the object) is an inseparable constituent of the word. So, to speak of their relationship as non-eternal is a contradiction in terms. We ignore this fact and treat a word as something existing separately from the object and it is this tendency that obstructs our attempts to make progress in grasping the nature of apaurusheyatva. The relation between a word and its object is also independent of individuals or convention. Since the identity of the object itself is independent of an individual, the nature of the object too is independent of the individual because it is the nature of the thing in the world whose identity the word is denoting.

On Convention

It is not easy to grasp how a word chosen by convention can be eternal or have an eternal relation to its meaning. One finds it difficult to dislodge the idea that before convention chooses the sound-form (of the word) to denote an object, it would have had no relation to that object. There can be no answer to this question from a worldly perspective; the answer can come only from a transcendental perspective. What is convention? What was it that made a particular group of people come together to form a language-speaking community? Creation proceeds out of the adrshta of jivas. That adrshta on account of which creation proceeds, that very same adrshta is responsible for a particular group of people to be born on earth and their lives to interleave with those of one another, and it is the same adrshta on account of which the unmanifest eternal word comes forth into the created world as a ‘choice’ of the language speaking community.

THE PROOF

This is a summary based primarily upon the translation of Jaimini Purva Mimamsa Sutras by Ganganath Jha and the translations of Kumarila Bhatta’s Slokavartika. This section is in five parts according to the subject matter of the sutras. In the original article, Naik discusses each sutra and its bhashya (commentary) separately. For this article, we have condensed each sutra and its explanation into one unit.

Part I – The Context

This part shows the context in which the sutras (1.1 to 1.5) relating to the eternality of words arise.

1.1: Now, therefore, (there must be) an inquiry into (the nature of) Duty.

1.2: Dharma or Duty is (something) desirable and the only source of its knowledge is Vedic injunction.

1.3: An inquiry into the means of the true knowledge of Dharma becomes necessary.

1.4: That cognition of a man which proceeds upon the contact of the sense-organs with existing objects, is sense-perception; and this is not the means of knowing dharma; because it apprehends only objects existing at the present time.

1.5: On the other hand, the relation of the word with its meaning is inborn (and eternal); consequently injunction (which is a form of a word) is the means of knowing dharma; and it is unfailing in regard to objects not perceived (by other means of knowledge); it is authoritative (the Word par excellence), according to Badarayana, especially as it is independent or self-sufficient in its authority.

Part II – Objections To The Doctrine Of Eternality Of Words (Sutra 1.6 to 1.11)

1.6: Some people hold that the word is non-eternal because we always find them come into existence by the effort of the person using or uttering it; and such an existence can only be evanescent.

1.7: Word must be evanescent because, in fact, we find that it does not continue to exist for any length of time; one moment pronounced, and the next moment gone.

1.8: Words must be non-eternal because we find people making use of the word ‘karoti’ (produce) with regard to words. Just as they say ‘ghatankaroti‘ (produce the jar), similarly in the case of words, they must mean ‘he makes or produces the word.’

1.9: We find that more than one person and in more than one place at the same time hears a word. For example, one may hear the word ‘cow’ at the same time in Kashi and in Patna by different people. For a thing to exist simultaneously in many places, the thing would either have to be an all-pervading substance or it would have to be a limited thing made existent in different places. Since the word is not an all-pervading substance, it follows that when perceived by different people at different places, it produces in those different places. Thus, any single word is not one, but many, all produced in different places.

1.10: In many cases the words which appear in the original form become modified into another form. Undeniably, there is a modification in the case of words; and hence, words are non-eternal.

1.11: In the case of a jar manifested by lamps, the jar remains the same even if hundreds of lamps illumine it. But the volume of a word is greater when pronounced by many people as compared to the volume when a single person pronounces it; therefore, it proves that a word is non-eternal because if it were the manifestation of an eternal word, the volume would have been the same and unmodified irrespective of the number of people pronouncing it.

Part III – Refutation Of Objections And Establishment Of Eternality Of Words (Sutras 1.12 to 1.23)

1.12: The objector says that words are non-eternal because they are a product of effort and are momentary. However, Mimansa says that the effort of the human utterer simply manifests, or renders perceptible, the word that has always been in existence. Whether we regard the eternally existent word as manifested by human effort, or as brought into existence by the utterer, the perceiving of the word would be only for a moment. Thus, the objection lacks the capability of dislodging the doctrine of eternality of words.

1.13: The objection says that a word cannot be eternal because it appears clearly to be impermanent. But the argument is fallacious because only the eternality of words can explain satisfactorily the momentary perception of the word. The word heard at one moment and not at the other is because it is only at one moment that the manifesting agency (human utterance many times) is operating towards its manifestation, and not at all moments. Whenever a man goes on uttering the word, we hear it; so as long as the utterance is operating, the perception is there; when the utterance ceases to operate, the perception ceases thus showing that what the utterance does is only to manifest, or render perceptible, what is already existing. If, on the other hand, the word comes into existence by the utterance in the same manner as the potter produces the jar, the word would continue to exist even after the utterance has ceased to operate just as the pot continues to exist even after the productive agency ceases. There is no production or creation of the word as there is in the case of a jar. What the manifesting agency of the utterance does is to remove or set free the obstruction that had impeded the manifestation of the word and allow it to manifest through the vocal instrument of the utterer.

1.14: The objection (purva-paksha) says that people make use of the word ‘produce’ with regard to the word. However, the production of the word implies the manifesting agency ‘utterance’ and not to the word. To clarify, production refers not to the production of the word but to the act of uttering so that the word manifests.

1.15: The objector says that like the sun, the word-sound heard at the same time by different people in different places proves that the word is not one, and is not eternal. This hardly proves that the word is many and transient. The example of the sun in fact weakens the position of purva-paksha. The sun seen at the same time by many persons at different places is only one and eternal. In the same manner, it is quite natural that the word should be one and eternal, and yet different people at different places at the same time can perceive it.

1.16: When pronouncing the two words ‘dadhi‘ and ‘atra’ pronounced in close proximity, we have the form ‘dadhyatra’, and being a modification of the word proves that words are not eternal. What is modifiable is non-eternal. The reply is that this is not so because in the form ‘dadhyatra’ the syllable ‘dhya’ is not a modification of the original syllables ‘dhi‘ and ‘a’; it is an entirely different letter. If the form ‘ya‘ as occurring in ‘dhya’ were a modification of the ‘i’ of ‘dadhi’ and ‘a’ of atra, then there would be no ‘ya’ apart from these letters. For example, ice being a modification of water, there can be no ice without water. But in the case of ‘ya’, there is no such inseparable connection with ‘i’ and ‘a’ as there should be between the original and the modification.

1.17: When many persons utter the same word, we perceive that the magnitude of the word undergoes an increase which shows that the word is liable to change thus proving the transient nature of words. In reply to this, when many persons pronounce the same word, what happens is not any change in the word itself, but only in the loudness of the tone, which becomes louder or fainter as the number of persons becomes more or less.

1.18: Refuting the objections of the adversary, there are further reasons to support the doctrine of eternality of words. The whole idea of the transience of words is that the utterance of a speaker brings the word into existence. However, we utter words not for the purpose of producing or creating a word, but for the purpose of expressing what the word denotes. The word has to be known a priori because otherwise there would be a lack of knowledge of the very thing which needs expression. And also, the purpose of verbal expression would not serve if the word uttered were transient. If destroyed immediately after utterance, it would not be in existence at the time that the hearer would need them to comprehend its meaning. The very fact of the comprehension being there in the mind of the hearer shows that the word we utter is not evanescent, but is lasting and eternal.

1.19: We find that every word, as a word, on several occasions is invariably recognizable by all people as being the same; whenever we hear a word – ‘cow’ for instance – we always recognize it as the same word ‘cow’ that we had heard on previous occasions. This recognition of sameness is with regards to all words and in the minds of all. the word heard and used today is precisely the same heard from time immemorial; that is to say, it is eternal.

1.20: When pronouncing a certain word (like cow) more than once, we say that we have used the word ‘five’, ‘ten’, or ‘twelve’ times. We do not say that we have used ‘five’, ‘ten’, or ‘twelve’ different words. If the word produces and destroys each time, we should have spoken of so many words and not of the same word as spoken so many times. Thus, universal usage also shows that the word is the same whenever used; that is to say, it is eternal.

1.21: In the case of all things that are liable to destruction people always find some cause of destruction; there is no such cause or agent for destruction perceptible in the case of words; consequently, we cannot admit of such destruction; and words must be ‘indestructible’, that is, eternal.

1.22: The opponents of the eternality of words (Nyayaikas in this case) bring forward the Vedic text ‘the air becomes the word‘ in support of the contention that the word has a beginning as it is a mere combination of air-particles. But this text cannot refer to what we know as the ‘word’. The ear cannot perceive air, according to the Logicians, being perceptible by the sense of touch alone.

1.23: There are texts which say ‘vacha virupinityaya’ – ‘by the word which is unmodifiable and eternal’. There the word is distinctly eternal. Stress is on the eternality of words; if words have an origin, they cannot be infallible. Such origin would have to be some intelligent person, and no such intelligent person is infallible. Hence the fallacious view regarding the non-eternality of words would strike at the infallible authority of the word – and of the Veda, which is a collection of words – upon which the whole fabric of Dharma rests.

Part IV – The Eternality Of Veda (Of Vedic Vakhyas)

The sutrakara first presents the objection of the adversary in sutra 24 and then refutes it in sutras 25 and 26 to establish the eternality of the Vedas.

1.24 (the objection): We grant that words express their meanings and that they are eternal; all that this proves is that words provide us with correct ideas; how does this prove the authority of the Vedic injunctions? These injunctions are in the form of sentences containing more than one word; and for the comprehension of a conglomeration of words, we need something more than the comprehension of the meanings of the component words. Consequently, the Mimamsaka has succeeded in establishing the authority of words only and not in establishing the authority of the Vedic sentences.

In the sutra occurs the word ‘avachanah‘ meaning ‘not expressive (of the meaning)’. Some people read this as ‘rachanah‘ which would make the sutra read as follows: “Even though words were) eternal, the meanings of sentences must be regarded as having an origin in human agency, and for this reason, they cannot be accepted as eternal and authoritative on matters relating to dharma as they do not depend entirely upon the meaning of eternal words.”

1.25 (the reply): The meaning of the sentence does depend on the meanings of the words composing it; there is nothing to prove that the sentence has any other meaning than that afforded by the component words. For instance, in the sentence ‘agnihotranjuhuyat svargakamah’ we find that the word expressive of the Agnihotra sacrifice and also the word expressive of desiring heaven (svargakamah) are both in close proximity to the word ‘juhuyat‘ which denotes the act of offering. The meaning afforded by this sentence is obtained through the signification of the two former words taken along with the signification of the verb. The meaning is that ‘one desirous of heaven should offer the agnihotra‘, which is nothing more than the denotations of the three words linked together. Hence, when the meanings of the words are eternal, sentences formed by these words are also eternal. There is no incongruity in the view that the Veda is the trustworthy authority for all matters relating to Dharma.

1.26: In ordinary usage, it is only when we know the meanings of each individual word that we can use or comprehend the meaning of the sentence; from this analogy, the meaning of the sentence depends upon the meanings of the words. That is to say, it needs admission that the meaning of the sentence ‘agnihotranjuhuyat svargakamah’ is nothing more or less than what is signified by each of those three words.

An Explanation: There is a tendency among modern people to treat the word-sound and the object that it refers to in a disjunct manner isolated from each other. It is this tendency to divorce the two which makes it difficult to grasp how a sentence may be eternal; for even if granted that words are eternal, it seems unimaginable that words can come together to form a sentence without human agency. The difficulty arises because we treat words and sentences in isolation, by themselves, just as we treat objects such as jar, table, etc. in isolation from other objects. While the components of a jar such as particles of clay simply exist in nature, the production of a pot needs human agency for the particles of clay to come together as a pot. When words are in isolation from their meanings as other objects then it appears that the same kind of agency would require to produce sentences. But sentences are related to knowledge and the nature of words as signs obviates the need for any such thing as the production of sentences from a conglomeration of words.

A word is something that is comprehensible by an idea binding together the phonemes. This idea – the binding idea, is the meaning. The meaning represents the knower’s knowledge of the word. Now, a knower’s knowledge does not exist in the form of knowledge of meanings of single objects alone. They exist as all kinds of knowledge such as knowledge of actions, causes, and so forth. Single words cannot represent these kinds of knowledge.

Even single words exist as parts of sentences in a knower’s field of consciousness as explained by Sri Shankaracharya: “In every word, there is the potentiality of a sentence ‘it exists’. When someone says ‘tree’, one understands that it exists…For bare words, like bare letter-sounds are meaningless, and do not amount to communication. Just as one aims at indicating a word by joining together the letter-sounds, so with words too: the means of constructing a sentence is by looking to other words as well. So, validity is in the sentence alone, since there is no understanding of the object from the use of a word in isolation. Even where an isolated word (like the name Devadatta) is supposed to be its context, still inevitably it supplements in the mind with the sense of existence, so that the word means ‘It is Devadatta’ and so on; without context, it is not intelligible.” (Vivarana on Yoga Sutra, III.17).

So, the eternal existence of sentences is the eternal sign in Consciousness that refers to the eternal object in the Omniscience of Brahman. Words also need not be manifest as speech for them to reside in Consciousness. This explains how sentences always persist in Consciousness and are eternal.

Part V –The Veda Is Apaurusheya (It Has No Human Author)

Sutras 27 and 28 present the objections and sutras 29 to 32 provide the refutations of these objections and the final establishment of the Apaurusheyatva of the Vedas.

1.27: According to some people the Vedas are the work of human authors; being, as they are, named after men. We find various sections of the Veda named after men like ‘Kathaka’ after the name of Katha, ‘Paippalada’ after the name of Pippalada, and so forth.

1.28: The Veda mention many non-eternal things. We find such statements in the Veda as ‘Auddalakih akamayata’ (Audalaki desired) and ‘Babara pravahani’ (Babana desired), and so forth. The mention of persons and events shows that the Veda cannot be eternal. That is to say, the presence of such sentences as the above proves that the sentences were composed long after the persons spoken of therein lived on the earth. That is to say, the Veda has had a beginning in time.

1.29: However, we have established the eternality of all words, whether divine or human. Hence the objection is groundless. We need to answer the arguments put forth by the opponent.

1.30: The name of the Vedic sections is based upon exceptionally excellent study and teaching of that section by a particular person. These persons had direct insight and were the first to expound them.

1.31: The other is only a similarity of sounds. As for the mention of the names of men and things in the Veda, there is nothing to show that the word found in the Veda was actually the name of a person. It is, in fact, a resemblance arising out of the fact that men and things took these names. The names of persons used in the Vedas are common nouns and not proper nouns. The persons bore the names subsequently in the cycles of creation. Hence, this argument of the objector does not detract from the eternality of the Vedas.

1.32: The opponents of Vedic authority argue that the Veda cannot be authoritative and trustworthy because it contains such apparently absurd statements as ‘the cows sat at the sacrifice’, ‘the trees performed the sacrifice’, and so forth. In answer to this, though these statements are absurd when taken by themselves, they cease to be so when taken along with the context in which they occur. All these sentences are the section dealing with a certain sacrifice; and in praise of this sacrifice, the declaration is that so excellent and so manifestly desirable are its results that it induces even trees to perform it. It is only natural that such intelligent beings as men should perceive the excellence of the action, and engage in performing it. There is nothing incongruous and absurd in the sentence if thus intelligently interpreted.

Thus then the Veda, not being the work of a human author (whereby it is free from all the discrepancies consequent upon such authorship) and there being nothing in the text of the Veda itself that shakes this authority, it must be admitted that it is a trustworthy and authoritative source of knowledge on all matters relating to Dharma; and as it has been shown that no other source of such knowledge is available, the Veda must be also acknowledged to be the only source of knowledge relating to Dharma.

CONCLUSION

This is perhaps a rare attempt to explicate the idea of the apaurusheyatva of the Vedas. The most important aspect to understand here is that apaurusheyatva does not mean an absence of knowledge of the authors of the Vedas but knowledge of the absence of human authors. This criterion is of utmost importance when a scholar approaches the texts. Even the modern-day Advaitins, a little detached from the traditional understanding, make a mistake here. Of course, Chittaranjan Naik makes it clear this series of articles is meant for educating people who are not familiar with the theme of apaurusheyatva of the Vedas. It is not meant to be a formal proof of Veda’s eternality, which requires more work.

Sanskrit is very strict about the use of words and their meaning; it also developed construction rules for words and word meanings instead of building dictionaries. That is, the speakers of this language formulated linguistic rules to understand the meanings of words and sentences instead of seeking meaning primarily in authorial intentions. As Dr. Balagangadhara says, when Indian culture claims that the Vedas do not have a human author, it becomes impossible to ask questions about authorial intentions. That is, ‘why were Vedas written or spoken?’ is more difficult to answer than the question ‘why did God call Moses to Mount Sinai?’ God’s word, the Bible, itself answers these questions. However, for such questions about the Vedas, our texts do not raise answers, though many Indologists do. One of the facts that upset Indologists about Indian texts is precisely this question: who wrote it and why? Indian traditions consider these questions to be irrelevant since the Vedas are eternal and unauthored; hence, the dating, authorship, and intentions of the authors remained inconsequential in seeking liberation while diving deep into the texts.

Leave a Reply