The elusive dream of ‘Equality’, whether in the form of ‘Opportunity’ or ‘Outcomes’, tantalises many, yet evaporates like a mirage in the real drama of human society. In electoral politics, politicians deftly choreograph their campaigns using these themes of social justice, equal opportunity, or outcome equality to garner votes. Politicians often stage appeals to the audience’s sense of justice and fairness, promising to mend the grievances of marginalised groups. However, whether these dissonances are genuinely resolved, or political disinterest takes centre stage, the misapplication of these principles — such as the Policy of Reservation or the PoA act — can inadvertently lead to a ‘Tyranny of the minority,’¹ potentially endangering the democratic framework.

In The fable of Antisthenes², illustrates how debates on achieving absolute equality have long been a source of contention and difficulty. The Hares addressed an assembly with Lions and argued for equality or the apophthegm attributed to Aristotle:

“The worst form of inequality is to try to make unequal things equal” ³

![Hindman LLC (Bill Ross). (2021). A Roman Marble Portrait Head of Antisthenes [Marble sculpture]. Retrieved from [A Roman Marble Portrait Head of Antisthenes (hindmanauctions.com)]](https://pragyata.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Ambedkar-1-683x1024.jpg)

“Equality as a moral or political imperative… is the antonym of every legitimate conservative principle. Contrary to most Liberals, new and old, it is nothing less than sophistry to distinguish between equality of opportunity… and equality of condition…. For only those who are equal can take equal advantage of a given circumstance. And there is no man equal to any other, except perhaps in the special, and politically untranslatable, understanding of the Deity. Not intellectually or physically or economically or even morally. Not equal!”

In the tug-of-ideal between the modern left and right, both dance on the tightrope of Equal Opportunity or Equal Outcomes, radicalizing notions that are more ethereal than earthly. The journey toward these unattainable ideals necessitates a heavy-handed approach of authoritarian social reconstruction, forcefully reshaping the societal fabric through reforms that ultimately fray the traditional structure. Comprehending these notions is crucial for unravelling the potential peril embedded within political ideologies such as Ambedkarism. Although they may present an alluring facade, they harbour the capacity to breed schisms, disintegrate societal cohesion, and ultimately ignite the flames of anarchy.

Ambedkarism, as its name implies, is a Reformist social and political doctrine set in motion by Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar. To understand it better, let’s first sketch the canvas of the man’s life and then embark on a voyage into the depths of his writings.

![Babasaheb Ambedkar as a Lawyer in Bombay High Court, 1 January 1923 [Photograph]](https://pragyata.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Ambedkar-2-592x1024.jpg)

In Arun Shourie’s meticulously researched and audacious publication, ‘Worshiping False Gods,’⁵ he underscores Ambedkar’s lack of advocacy for the liberation of this land from colonial rule. In fact, Shourie calls him a ‘Vehement Opponent of the Freedom Movement.’ In his long essay titled, ‘A Plea to the Foreigner’ he makes his views clear:

“It will be found that the Fight for Freedom led by the governing class is, from the point of view of the servile classes, a selfish, if not a sham, struggle. The freedom which the governing class in India is struggling for is freedom to rule the servile classes. What it wants is the freedom for the master race to rule the subject race which is nothing but the Nazi or Nietchian doctrine of freedom for superman to rule the common man.”

Simultaneously, Ambedkar wielded a sharp analytical scalpel to dissect Indian leaders, with Gandhi often finding himself squarely in his critical crosshairs. A significant portion of Ambedkar’s writings brimmed with venom directed at civilization and religion, with endeavours to fragment the societal fabric, and the cultivation of rifts among different castes. Ambedkar’s ideology can be seen as somewhat parallel to that of a Cultural Marxist.

Madhu Limaye, a committed socialist and esteemed parliamentarian, rightly held Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ in the same vein as the ‘Communist Manifesto.’⁶ According to Limaye, Ambedkar’s unwavering call for the eradication of caste was paramount, as it paved the way for the emergence of class distinctions and the emerging caste struggles. ‘Annihilation of Caste’ acted as a potent munition for the colonial and missionary interests, furthering the assault on the three ‘Upper’ castes as perennial oppressors perpetrating some long-standing and systemic injustices upon the Śūdras. While exuding acrimony and framing the Upper Caste within a narrative reminiscent of the Nazis’ treatment of Jews, Ambedkar proceeds to articulate his aversion for Caste, Scriptures, and Hinduism as a Religious Tradition.

In his words:

“Caste is not a physical object like a wall of bricks or a line of barbed wire which prevents the Hindus from co-mingling and which has, therefore, to be pulled down. Caste is a notion, it is a state of the mind. The destruction of Caste does not therefore mean the destruction of a physical barrier. It means a mean notional change. Caste may be bad. Caste may lead to conduct so gross as to be called man’s inhumanity to man. All the same, it must be recognized that the Hindus observe Caste not because they are inhuman or wrong-headed. They observe Caste because they are deeply religious. People are not wrong in observing Caste. In my view, what is wrong is their religion, which has. inculcated this notion of Caste. If this is correct, then obviously the enemy you, must grapple with, is not the people who observe Caste, but the Shastras which teach them this religion of Caste.” ⁷

Ambedkar proceeded to make unfounded assertions to the British authorities, painting a picture of Śūdras’ unwavering loyalty to the British. He claimed that the Scheduled Castes had served as the earliest wellspring of manpower for the East India Company, and it was their assistance that facilitated the British conquest of India. His demeanour unmistakably exhibited megalomania, driven solely by the aspiration to stand alongside Jinnah as a sole leader for specific communities, crafting a narrative around imagined atrocities. Furthermore, he fearlessly ignited the Manusmṛiti in 1927, decrying it as a fountainhead of caste-based injustice. Despite such political stunts, even in the constituencies predominantly populated by Harijans, he found himself on the losing end against the Congress, trailing by a significant margin.

Further complicating the multifaceted nature of his character was his connection with tainted figures like Periyar and Jinnah. EV Ramaswami (the father of the Dravidian movement) at Viduthalai (July 10, 1947) addressing Dalits:

“I strongly believe that Ambedkar alone can eradicate atrocities against the Panchamars. Ambedkar should be your leader.” ⁸

During the Round Table Conference, ⁹ Ambedkar found himself on the opposite side of the national freedom struggle — supporting the British — while standing alongside Jinnah¹⁰ in their joint vision for the country’s ‘deliverance’ from Congress.

Post-independence Ambedkar continues to further demonstrate the extent of his opportunism and megalomania, revealing the composition of his skewed character. Despite hurling abuses at Gandhi and other Congress figures, being in bed with the likes of Jinnah and Periyar, collaborating with the British, and lack of electoral victory — Ambedkar, as Shourie tells us, pleaded to Gandhi through Babu Jagjivan Ram for a position in the nascent government. The government appointed him as the head of the Constitution Drafting Committee, sparking the creation of a new legend around Ambedkar as the architect of our Constitution. Contrary to this notion, Shourie contends that he wasn’t the true architect.

Ambedkarism fundamentally entails encapsulating the essence of Ambedkar’s life story and bringing his reformist and social justice ideas to fruition. In the later chapters of his life, Ambedkar orchestrated significant manoeuvres that etched deep marks on Indian society. In 1956, he orchestrated a monumental conversion to Buddhism, casting aside Hinduism due to its perceived oppressive and demeaning aspects. These actions encapsulated his lifelong dedication to social justice and his unwavering commitment to dismantling the culture, civilisation and religion of this land. Navayana Buddhism, where Ambedkar serves as the guiding light instead of Buddha, and the twenty-two vows¹¹ that accompany it, embody the very heart and soul of Ambedkarism.

In his vows, he took a stand against Hinduism, which he saw as a source of social inequality and oppression. He rejected the Hindu deities, including Brahmā, Viṣṇu, Maheśa, Rāma, Kṛṣṇa, Gaurī, and Gaṇapati. He consistently spat out venom directed at Hindu traditions, rituals, and the Varṇaśrama Dharma. In his writings, he uses profane and filthy language:

“I am disgusted with Hindus and Hinduism because I am convinced that they cherish wrong ideals and lead a wrong social life. My quarrel with Hindus and Hinduism is not over the imperfections of their social conduct. It is much more fundamental. It is over their ideals.” ¹²

His views on Lord Rama:

“When he [Rama] got tired of the Zenana (women) he joined the company of jesters and when he got tired of jesters he went back to the Zenana…Such is Rama.” ¹³

His views on Lord Krishna:

“Krishna who abandons his lawfully wedded wife Rukmini and seduces Radha, wife of another man and lives with her in sin without remorse.” ¹³

The list is endless.

Ambedkarism cunningly entices both the Left and the Right in India. Ambedkar’s commanding presence is most pronounced within the left-dominated educational setup, and thus it radiates outward from academia into the wider public, social sphere, and electoral politics. The Left, smitten with its Cultural Marxist undertone of social justice and radical equality, embraces his thoroughly rationalistic and atheistic philosophy. This extreme scientific rationalism contradicts religiosity, which relies heavily on faith and revelation. It’s not just a means to portray Hindu orthodoxy as superstition; he also deftly reshaped his Navayana Buddhism to snugly fit within that framework. When confronted with analogous aspects of the caste system or dogmas and rites in Buddhism, he engaged in a vehement battle of outright denial. With utmost dishonesty regarding ‘the principle,’ he twisted Buddhism into some ‘Cultural-Marxist Scientific Rational’ Religion, committing the ‘Fallacy of Equivocation’.

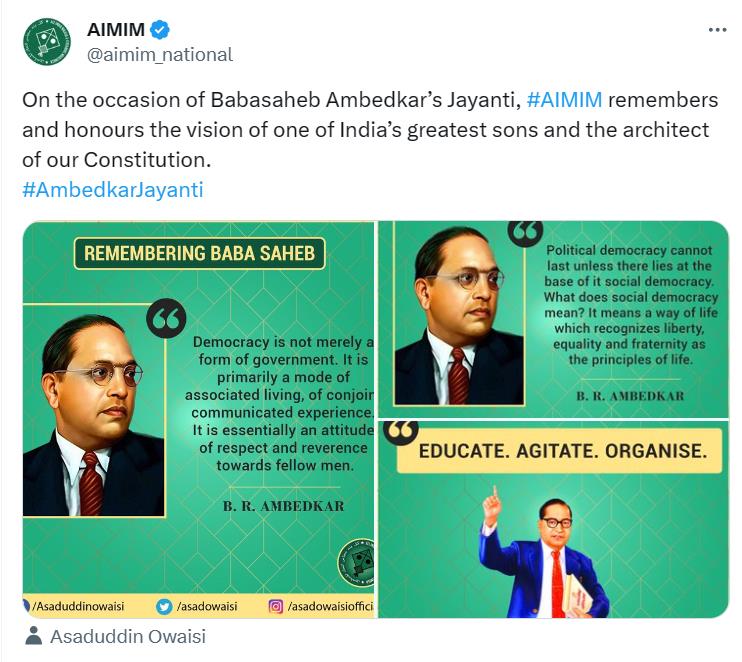

What’s more astonishing is the fact that Ambedkarism casts its shadow of influence just as prominently, if not more so, over the Right in India. Its co-optation by the right-wing and even certain religious factions (Both Hindus and Muslims) in India is nothing short of a lamentable tragedy, emblematic of their intellectual dearth.

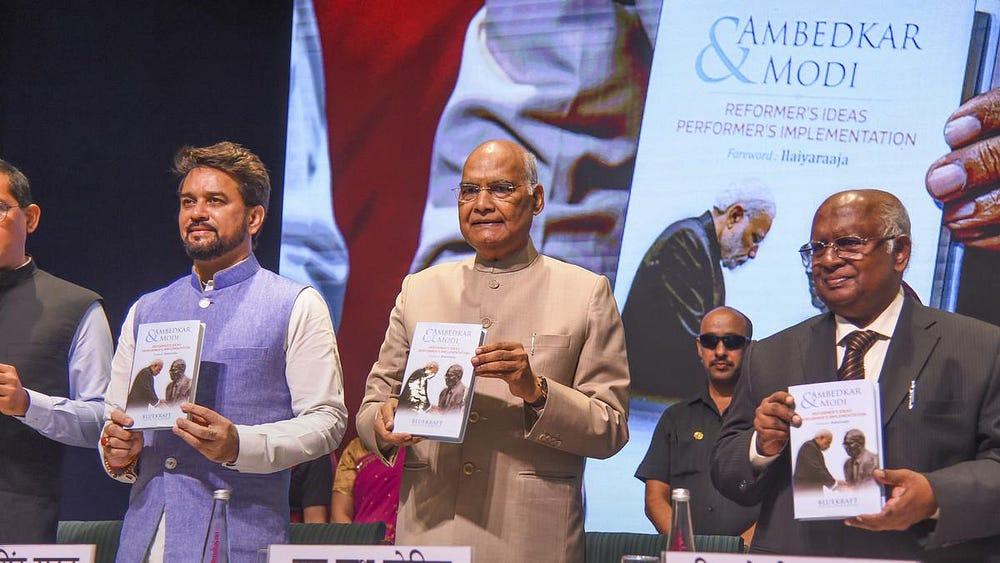

Throughout history, there are ample instances that depict Ambedkar’s strong aversion and contempt for the tenets of the Right-Wing Hindutva politics. In his contributions to Prabuddha Bharat, he engages in robust criticism of Savarkar and his political ideology. Regardless, there have been claims about Ambedkar’s strong connection with early RSS leaders like K.B. Hedgewar and M.S. Golwalkar. While lacking a firm historical foundation, it appears that the key motive behind these assertions and the strategic shift toward incorporating Ambedkar’s politics into Hindutva is to harness his quasi-divine status in the contemporary Indian state and his ‘scholarly’ depiction among India’s preeminent icons. The RSS-BJP not only includes Ambedkar in their list of honoured nationalist leaders but also prominently features him in a poster celebrating historic heroes of Hinduism, even though Ambedkar called for the annihilation of that very religion. From publishing works like ‘Manusmriti Aur Dr. Ambedkar (2014)’ ¹⁴ and ‘Prakhar Rashtra Bhakt Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar (2014)’ ¹⁵ to fervently advocating for him in speeches and writings by top national leaders, including the Prime Minister of India, the BJP-RSS leadership persistently seeks to align themselves with Ambedkarism, both in ink and in action. Former President Ram Nath Kovind even unveiled a book titled ‘Ambedkar and Modi,’ and interestingly the thematic title used is ‘Reformer’s Ideas Performer’s Implementation.’

Another rationale for invoking Ambedkar is to strategically extract his writings to push a particular agenda, exploiting his recognized authority and scholarly eminence. His writings are extensively used as a source by the Right-Wing Hindutva faction, particularly in discussions regarding Muslims in India, aiming to construct an opposing narrative. The critique of Abrahamics by a huge lot of political Hindus has turned into a critique of the very structure of all forms of religion and tradition. We as a society are afflicted with something akin to an autoimmune disease — which will end up turning us all into agnostics. The sole rationale for this group’s adoption of numerous ideas from Ambedkar, supporting his diabolical ideals of social justice and reform, and even rationalising the abuses he hurls on our deities and religion, is the fact that he criticised Muslims.

The manifold perils inherent in the social justice and reformist principles of Ambedkarism, which the State now openly embraces, have extensive ramifications on the collective mindset of society and state policies. Let’s understand it further by examining one of its most significant impacts: ‘The Reservation Policy’ and its implications. The Reservation Policy stands as our confession to the burden of baseless caste atrocity literature imbibed by our collective psyche. It’s the practical fruit borne from the dose of social justice and equality consumed by our society and electoral politics.

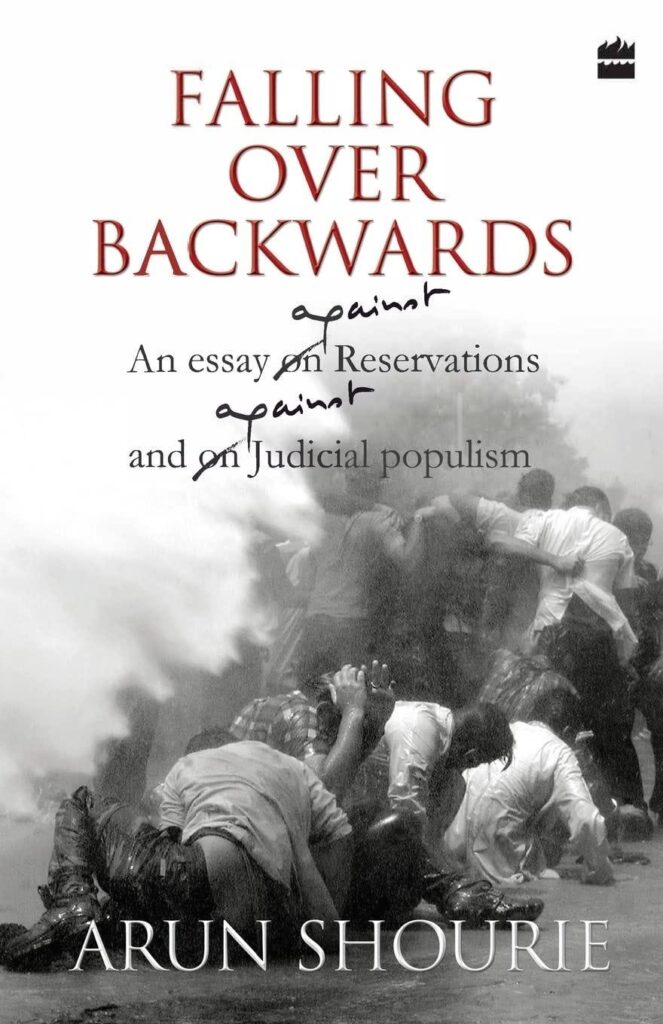

A Critical Look at ‘The Indian Reservation Policy’ in the Light of the Book ‘Falling Over Backwards’ ¹⁶ by Arun Shourie

Let’s pirouette into another of Arun Shourie’s works, ‘Falling Over Backwards,’ to garner an insight. Shourie constructs the groundwork, delving into the structure of this policy:

“The object of the framers of the Constitution was, as ours must be, quite the opposite. It was to wipe out the cancer of caste even from Hindu society. Only with the greatest reluctance did they agree to allow reservations for the Scheduled Castes and Tribes — for they felt that doing even this much would perpetuate caste distinctions. The reservations were, therefore, to be exceptions to the general rule.”

Thus, according to him, reservations don’t seek to obliterate caste, but rather, seem to nurture further divisions.

A quote by Shri Ram Swarup Ji on Caste, that I love referring to is:

“The self-styled social justice intellectuals and parties do not want an India without castes, they want castes without Dharma. This may be profitable to some in the short run, but it is suicidal for all in the long run.” ¹⁷

In the current political landscape, the caste identity is not just standing firm; it’s being fortified. Castes are being strategically played against each other, and what was once primarily religious and sociological is now wholly entangled in politics.

The aim of India’s reservation system claims to uplift those communities who have historically faced economic and social hardships. Shourie, with surgical precision in his analysis, has dissected this very bedrock of the reservation policy. He has unearthed historical cases, combed through constitutional amendments, and scrutinized excerpts from judicial judgments, to methodically unearth its loops. In his book, Shourie highlights how, during the British Raj, there was a remarkable tendency among the public to masquerade as ‘upper castes,’ thus leading to the gradual erosion of caste boundaries. The very foundation of the myth surrounding caste atrocities and upper-caste oppression crumbles when we pose the question: Did this scenario persist over the course of the thousand years of Islamic rule in India? If it did, we must ponder why it would have been in the best interest of Islamic rulers to govern in a manner that exclusively favoured the upper castes. The reality is that caste has consistently posed a hurdle throughout the reign of both the British and Islamic rulers. Both regimes went to great lengths to suppress the priestly and warrior castes, doing so with particular ferocity because they recognized these castes as potential challengers to their authority. These castes were not just an obstacle to the expansion and consolidation of political power but also to the spread of their respective religions.

Diving deeper, the Census’s influence looms large over the Reservation Policy’s very foundation. The traditional caste system underwent a significant transformation allowed by the British census, which shifted it from its original structure to a political classification. There was the phenomenon of ‘caste consolidation’, where numerous related castes and sub-castes came together under a single umbrella group, desiring to be collectively enumerated in this manner. Numerous castes, once designated as ‘lower castes’, eagerly adopted new identities claiming themselves Kshatriyas and Brahmins in their desire to shed the ‘lower caste’ label.

“‘There is… apparently a tendency towards the consolidation of groups at present separated by caste rules,’ the census reported in passages that should be bookmarked for the time when we will turn to judges of the Supreme Court who write about the institution as if we are still frozen in the day — in fact, in the pages — of Manu.

‘The best instance of such a tendency to consolidate a number of castes into one group is to be found in the grazier castes which aim at combining under the term “Yadava” Ahirs, Goalas, Gopis, Idaiyans and perhaps some other castes of milkmen, a movement already effective in 1921.’”

The perversion of the original caste framework into a political classification via the British census.

“The claim was that the caste deserved to be enumerated as a higher caste — Ahar as Yadava, as Yadava Kshatriya; Aheria as Hara Rajput; Ahir as Kshatiryas of varied superscripts; Banjaras as Chauhan and Rathor Rajput; Barhai as Dhiman Brahman, as Panchal Brahman, as Vishwakarma Brahman; Bawaria as Brahman, period; Bhotia as Rajput;… Chamar as Jatav Rajput;… Gadaria as Pali Rajput; Gujar as Kshatriya;… Jat as Jaduvanshi Thakur;… Kayastha as Chitragupta vanshi Kayastha, as Kshatriya;… Lodh as Lodhi Rajput;… Nai as Nai Brahman, as Pande Brahman;… Patwa as Brahman;… Taga as Tyagi Brahman…. One after the other, sixty-three castes, the list alone taking three full pages…. The point here is that each of them was aspiring to be and demanding to be elevated to a higher place in the social hierarchy.”

Amidst the wave of social justice reform movements, the tide of industrialization, and other influencing factors as well, caste boundaries gradually diminished in social significance while gaining political relevance. Interestingly, various communities registered themselves as distinct castes or caste groups in one census and as entirely separate castes or caste groups in the following census. The census, far from being a neutral reflection of an existing reality, was, in fact, instrumental in shaping the modern caste formations.

It’s not surprising that Yeatts, as a census commissioner, notes, “When caste names are shed like garments there is little point in enumeration that must perforce go by name.”

This inconsistency posed a challenge to the credibility of census data. Consequently, the British Raj decided to discontinue the caste-based census in 1931, citing the unreliability of the data gathered through this method. The seemingly insignificant 1931 census, which initially appeared inconsequential, paradoxically fuels the entire landscape of caste-based politics and reservations in present-day India. This seemingly meaningless census served as the blueprint adopted by the Mandal Commission.

Affirmative Action inadvertently only acts to amplify what it claims to abolish. I.P. Desai, the Sociologist stated in his concurring note to the Rane Commission,

“We would be legitimizing the caste system by State action as the British and pre-British Indian rulers did.”

Affirmative action in India only strengthens the Caste Consciousness, only to be exploited for Electoral gains. Quoting from an Essay by Sowell:

“Innumerable principles, theories, assumptions and assertions have been used to justify affirmative action programs — some common around the world and some peculiar to particular countries or communities. What is remarkable is how seldom these notions have been tested empirically, or have even been defined clearly or examined logically, much less weighed against the large and often painful costs they entail.” ¹⁸

Affirmative action in India sprouted its roots in the pre-independence era, but it truly bloomed when Ambedkarism became the guiding spiritual ethos of the nation. So, to keep up with the contemporary rhythm, let us understand it post-independence. India’s Constitution officially ushered in affirmative action for SC and ST groups in 1950. Over time, it expanded to include other Castes. Its triumvirate of domains are education, public employment and legislative assemblies.

Further In 1990, the Indian government, led by Prime Minister V.P. Singh, enacted the Mandal commission’s suggestions, which featured an allocation of 27% of positions in government employment and educational institutions to OBCs. This amplified the previous 22.5% allotment, which was originally based on birth, to a staggering 50%, all in the spirit of championing Social Justice and Equality. These policies were all anchored in the context of the fallacious and antiquated census from the very census of 1931.

In the words of Shourie,

“What is conceded once to appease an aggressive group, to pander to a vote bank, just cannot be taken back. It becomes the test of fidelity to the ‘cause’ — anyone who even suggests that there is a better way to help the very persons in whose name the concessions have been made is pounced upon as ‘Anti-Dalit’, ‘Anti-poor’… Society gets polarized, politics whirls, power gets congealed along those chasms. Far from being able to step back, what has been conceded in one round becomes the floor for the next.”

This is essentially how endeavours for radical equality crumble, paving the path to disorder. Why would a community relinquish a position of advantage once acquired? Why would a politician tamper with or retract that advantage when it could impact their voter base? The cycle is endless. Shourie further writes:

“At first the ceiling.

That becomes the floor.

That floor becomes a right.

That right having already been secured becomes the base from which to wrest more.

That it has been wrested in educational institutions becomes the rationale for demanding, and soon getting it in services…”

Chapter 10 — “From equality of opportunity to that of outcomes, From absence of disabilities to presence of abilities, From providing assistance to imposing handicaps” — is the most interesting chapter of Shourie’s entire work to understand the curse that affirmative action has actually become for this nation. It starts with the classic debate on equality of opportunity and outcomes.

“Justice O. Chinnappa Reddy says in Akhil Bharatiya Soshit Karamchari Sangh, thus reading his own goal into the Constitution. Equality of opportunity must be such as to yield equality of results and not that which simply enables people, socially and economically better placed, to win against the less fortunate, when the competition is itself otherwise equitable.”

While this might now appear quite unconventional to both advocates of reservations and those wary of its potential overreach and control in the pursuit of equality, it underpins the essence of all affirmative action and social justice. Can a society genuinely achieve a level playing field, or is it merely utopian idealism, perpetually looping affirmative action as reverse discrimination? While entrance examinations may present the facade of equal opportunity, do they genuinely achieve it when certain groups hold more inherent advantages? And if the goal is to counteract this privilege on the battleground of opportunity, manipulating outcomes becomes the sole recourse that social justice offers. This is precisely why the pursuit of fairness and equality often rings hollow. Has any society ever cracked the equality code, ended the crutch of affirmative action, and sustained a mosaic of diversity with a harmonious blend of language, religion, and culture? The self-evident response fractures their utopian vision. Various factors, spanning genetics, and epigenetics to a family’s financial situation, perpetually influence the balance in favour of specific individuals. This is how human societies function and one cannot do much about it.

The impact of social justice ideologies, notably Ambedkarism, has catalysed seismic shifts within academia, the Neo-Hindu mindset, and societal structures at large. This movement has rippled through various practical applications, prominently reflected in draconian measures such as Reservation or the PoA act, reshaping the landscape of state policies and societal norms alike. In India, affirmative action strives to level the playing field, aspiring for equal representation across all castes in every aspect of life. However, it raises eyebrows when a staggering 63% of undergraduate dropouts in Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) are from the reserved categories, ¹⁹ despite being admitted with nearly half the cut-off. Or a math instructor with minus 9.97 marks ²⁰ finds themselves teaching in Rajasthan, while general category candidates with significantly higher marks face disqualification. These examples of forced equality strike a dissonant chord.

What impact does a guilt-ridden conscience about a fictional history of atrocities have on society? Why do college campuses witness anti-Brahmin or Baniya slurs and slogans? EV Ramasamy once sought a Brahmin-free state of Tamil Nadu. His dreams seem to have come true. The Brahmin genocide in Tamil Nadu remains an unspoken topic. As pointed out by Jawaharlal Nehru ²¹:

“I am much distressed by the anti-Brahmin campaign continuously carried on by E.V. Ramaswami Naicker. I find that Ramaswami Naicker is going on saying the same thing again and calling upon people at the right time to start stabbing and killing. What he says can only be said by a criminal or a lunatic.”

Vishnu Tiwari, ²² who, after two decades behind bars, was exonerated by the Allahabad High Court, had been charged with offences like rape, sexual exploitation, and criminal intimidation under the Indian Penal Code (IPC), along with other sections of the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. In another incident in Fatehabad, Principal Neer Kumar ²³ pressed charges against Satish Sharma under the sections of the SC-ST Act and sent him to jail. This legal action stemmed from Sharma’s inquiry into financial irregularities, and the case filed suggested a motive clearly rooted in personal animosity rather than a pursuit of justice. Similarly, in Maharashtra’s Thane district, ²⁴ seven farmers were acquitted under the SC-ST Act after a villager accused them of an attack. The court later found the prosecution unable to substantiate the claims. In one incident after facing a decade and a half of charges under the SC-ST Act, the Hathras District ²⁵ Court finally cleared two Rajput men from Hathras Junction police station of all accusations. And this is all just the tip of the iceberg.

The Act’s definition of what constitutes an atrocity can often be found in the murky depths of vagueness, paving the way for its misappropriation and abuse. One particularly contentious aspect is Section 18A, which deems it an offence to pre-empt an arrest under the Act. Another chink in the PoA Act is the absence of a mandatory preliminary inquiry before making an arrest. Additionally, it lacks the provision for anticipatory bail, leaving those accused of atrocities against SCs and STs with no pre-trial bail option. The oppressive legislation reinforces the pervasive myth of Atrocity literature, primarily serving electoral agendas. While atrocities affect even Brahmins and various other castes in this nation, electoral narratives have overshadowed this reality, deeming it politically incorrect. Divisive lines are being etched between different caste and community factions in society.

These incidents, not particularly rare, stemming from the pursuit of egalitarianism and the assimilation of post-enlightenment values, prompt us to contemplate our present circumstances and the direction in which our society is heading. The question that emerges is: Do social justice, equality, and reforms reign supreme as transcendent values? Do religion, culture, tradition, and civilization solely encompass oppression and backwardness, or do they extend beyond the horizons of the contemporary cultural Marxist worldview we’ve embraced?

References:

- Ziblatt, D., & Levitsky, S. (2023, September 12). Tyranny of the Minority: Why American Democracy Reached the Breaking Point. Norton.

- Gibbs, L. (Trans.). (2002). THE LIONS AND THE HARES. In Aesop’s Fables (Perry 450; Aristotle, Politics 1284a).

- Peter, L. J. (1979). Peter’s People: And Their Marvelous Ideas. William Morrow. (The epigrammatic version of this paraphrase is likely based upon ‘Aristotle. Politics. Edited and translated by H. Rackham, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 1932. Book III, Chapter V, Section 8.’)

- Bradford, M. E. (1979). The Heresy of Equality: A Reply to Harry V. Jaffa. [Review of Harry V. Jaffa’s “Equality as a Conservative Principle”]

- Shourie, A. (2012). Worshipping False Gods: Ambedkar, and the Facts which Have Been Erased.

- Limaye, M. (2003). Manu Gandhi and Ambedkar: Policy and Other Essays.

- Ambedkar, B. R. (1936). Annihilation of Caste.

- Periyar, E. V. R. (1947, July 10). Speech at the Depressed Classes Conference, Mayavaram. Reported in Viduthalai.

- Ambedkar, B. R. (1930, November 20). Speech at the Plenary Session, Fifth Sitting of the Round Table Conference.

- Rao, K. V. Ramakrishna. (2001). The Historic Meeting of Ambedkar, Jinnah and Periyar. In Proceedings of the 21st Session of South Indian History Congress (pp. 128–136). Paper presented at Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai, India, January 18–20, 2001.

- Omvedt, Gail (2003). Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste.

- Ambedkar, B.R. (1936). Annihilation of Caste.

- Ambedkar, B.R. (1987). Riddles in Hinduism.

- Paliwal, K. V. (2014). Manusmriti Aur Dr. Ambedkar. January 1, 2014.

- Bhandari Ramaswamy, C. S. (2014). Prakhar Rashtra Bhakt Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar. January 1, 2014.

- Shourie, A. (2006). Falling over backwards: An essay on reservations, and on judicial populism.

- Logic behind the perversion of caste.” The Indian Express, September 13, 1996.

- Sowell, Thomas. (2004). Affirmative Action Around the World: An Empirical Study.

- Deccan Chronicle. (2023, September 21). Top Court To Examine SC/ST Reservation.

- Qureshi, A. (2018, February 25). जीके में जीरो, गणित में लाया -9.79 अंक, अब पढ़ाएगा गणित [Zero in GK, brought -9.79 marks in maths, will now teach maths]. राजस्थान पत्रिका [Rajasthan Patrika].

- Nehru, J. (1964). Letter to Kumaraswami Kamaraj. Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Second Series, vol. 40.

- NDTV. (2021, March 3). “My Body Is Broken…”: UP Man Acquitted Of Rape After 20 Years In Prison

- Neo Politico. (2023, December 22). Teacher sent to jail under SC-ST Act for asking questions on financial irregularities.

- Law Trend. (2023, April 7). Court Acquits Seven Farmers Accused of Attacking Villager.

- Neo Politico. (2023, December 07). Hathras: After Fifteen Years, Two Rajput Men Acquitted in False Dalit Atrocity Case.

Leave a Reply