This essay investigates how the legitimacy of a language supports or facilitates symbolic violence and self-censorship among minority languages, as well as how language laws and practices legitimise languages and how they affect diverse social groups. It also considers what may be done to keep linguistic ideology as a multifaceted phenomenon.

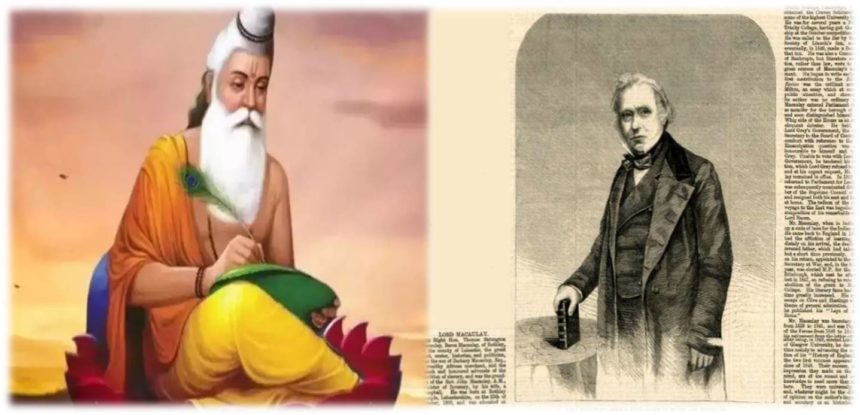

A Call for the Linguistic Decolonisation of Bharat

The spirit that runs through the veins of Bharat is not what we popularly call ‘Unity in Diversity’, but rather ‘Diversity in Unity’. Bharat, as a multiethnic, multicultural, and multilingual country, is home to a diverse range of ethnic groups, cultural identities, religious sects, castes and creeds, and linguistic identities. The two hundred years of British imperialism and the ongoing globalisation process have subjected Bharat to a colonial fabric of thought. It is a significant source of concern.

During the period that Bharat was under colonial rule, several European Indologists and missionaries not only visited the country but also subverted the Bharatiya consciousness to a point at which they could successfully manipulate it to their wits and whims. Communication was crucial in imposing colonial policy on the native people of Bharat. As a result, they learned and practised Bharatiya languages using various colonial tools such as language surveys, mapping, and language documentation (standardisation). To civilise the ‘backward’ native people they began to impose English education, which produced an elite class of Bharatiyas, known as ‘Brown sahibs’ in modern parlance, who could help them establish British rule deeply in Bharat.

The imposition of English education was a European colonial invention designed to construct and reproduce language as a fixed and autonomous entity, which dissected and fragmented local multilingualism into multiple, named languages. As a result of the colonial ideology of monolingualism, bilingual/multilingual people with fluid and alternative language practices were excluded and marginalised. Moreover, it dissuaded the Bharatiyas who were natural polyglots; a fact that is too often overlooked by politicians and litterateurs.

The monopoly of English over Bharat’s local population valorized English as the language of salvation and progress, while all other indigenous languages were rejected as being unsuitable for education and other public uses. This severely limited the ability of language minorities to demonstrate their full potential for personal growth and societal benefit. Another major source of worry is the neoliberal ideology of language instrumentalism, which emphasises the importance of English and defends colonial legacy, resulting in the linguistic hierarchy at local levels. The label of English as a worldwide language and a prominent educational language has decertified multilingual Bharat’s linguistic, cultural, and epistemic identities. By creating hierarchies, dichotomies and borders among languages and in the language learning process, colonialism emphasised the superiority and hegemony of dominant ideologies and epistemologies. Decolonisation of the intellect indeed begins with the decolonisation of languages and vice versa.

Ngugi Wa Thiongo, a Kenyan novelist and post-colonial theorist, wrote a book called ‘Decolonising the Mind: the Politics of Language in African Literature’ that calls for linguistic decolonisation. He discusses language and its beneficial role in national culture, history, and identity throughout the book. According to the most recent census study, Bharat is one of the finest examples of a multilinguistic area, where more than 19,500 languages or dialects are spoken as mother tongues. Out of these, 121 languages are spoken by 10,000 or more people. In what is known as the “8th Schedule” of the Constitution of India, only 22 major languages are recognised as of now. They include Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Nepali, Oriya, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu, Bodo, Santhali, Maithili, and Dogri. Most of the Bharatiya languages are still standing out of the league, without being even noticed or recognised. It is one’s mother tongue that helps to mould one’s perception of the world.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis of linguistic relativity claims that the structure of a language affects its speakers’ worldview or cognition, and thus people’s perceptions are relative to their spoken language. It holds true to an extent.

The example of how the Inuit Eskimos describe snow is a well-known example of linguistic relativity. ‘Snow’ has only one word in English, but numerous words in the Inuit language are used to describe it: ‘moist snow’, ‘clinging snow’, ‘frosty snow’, and so on. As a result, the hegemonic ideology of monolingualism deprives diversified groups not only of their access to the native language but also of their thinking ability. This can only lead to lowered self-esteem, and a sense of disempowerment, and reinforces linguistic discrimination and chances of attaining proper formal education and societal success.

The situation in Bharat is alarming.

“India may have lost 220 languages since 1961.” says Ganesh N Devy, founder-director of the Bhaasha Research and Publication Centre, and the Adivasi Academy, in Vadodara.

“Our country, more than any other in the world, has 197 languages in varying degrees of endangerment. Tribal languages are rich in information about a region’s flora, wildlife, and medicinal herbs. This information is typically passed down from generation to generation. When a language fades, however, that knowledge system vanishes totally. With the loss of language comes the loss of all culture, identity, and solidarity, as well as the loss of Man himself.”

The death of a language does not occur when it ceases to exist, but when its speakers cease to exist. In Bharat, it is primarily due to colonialism and its after-effects. With the spread of formal English education and its popular rhetoric as Lingua Franca, it has become mandatory for every sphere of a Bharatiya‘s life. Thus the European world, which only contributes to 3% of the world’s linguistic population has been able to establish its superiority and worldview over other worlds which are richer linguistically.

Linguistic Imperialism is a common phenomenon nowadays. With the onset of colonisation, one can see direct traces of it. It is in a fact a novel way of cultural imperialism. Till this time, due to the advancing process of globalisation, the impetus growth of linguistic imperialism has seen no end. The position of English as the Lingua Franca and its monopoly over the educational system indeed generates an identity crisis in non-English countries where their languages are at risk.

Here lies the significance of Linguistic decolonisation which aims to strike down the linguistic hegemony and monolingual ideologies created by colonialism.

A ground-level effort is required to become counterproductive. We must impart Engaged Language Policy (ELP), which conceptualizes our country’s language policy from a transformational and equitable standpoint. It involves ethnographically based and locally based efforts to decolonise the dominant language ideologies that have produced current and mainstream language policy ideas. According to the ELP, language policy actors should engage in “critical debate to unravel, criticise, and reform dominant language ideologies, policies, and practices.” It also recognises the marginalised people’s identity as ‘critical expertise’ and their right to research language policy issues.

So what can we do? Listed below are some recommendations:

- Increasing pride in one’s own identity and culture.

- Systematically breaking down colonial language hegemony by denaturalising its discourse.

- Raising awareness of the status and relevance of indigenous languages.

- Bringing Indigenous languages (particularly tribal languages) to national notice by addressing the pressures they endure.

- Providing appropriate resources to broaden the scope and promote linguistic study in indigenous languages.

- Promoting a bilingual/multilingual environment in educational and professional settings.

- Aiding local participants in meeting their language, educational, economic, and social needs.

- Empowering marginalised populations and encouraging them to engage in language activism in support of equitable language policies.

- Training and promoting the use of indigenous languages by indigenous media organisations.

- Improving teacher training for Indigenous community educators.

- Ensuring that the government recognises and works with these languages as part of its Closing the Gap programme.

- Understanding sociolinguistic injustice and calling for linguistic democracy.

The glory of the ancient civilisation of Bharat can be reclaimed only if we stop glorifying and prioritising English; and focusing on promoting the use of Bharatiya languages – because the language, the shabda, is the carrier of the tejas and intent of the thought. When it comes to Bharatiya dharmik and samajik literature, much is truly lost in translation.

Leave a Reply