INTRODUCTION

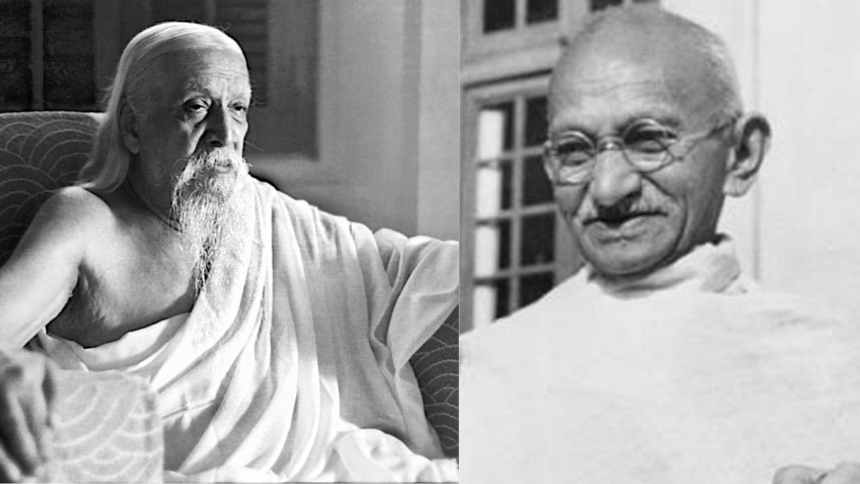

It has been a persisting intellectual endeavor to compare the two great personalities of India- Gandhiji and Sri Aurobindo. Both combined their politics with spirituality; however, each one had his own way of interpreting and implementing this philosophy of ‘spiritual politics.’ Both Gandhiji and Sri Aurobindo had strong ideas regarding the past of India, the solutions to the contemporary independence struggle, and the future path of India. It is an interesting debate as to who was clearer and more relevant to modern India. Supporters on both sides take strong positions.

Whatever may be the truth, Sri Aurobindo needs an urgent rediscovery. His equally, if not more, important voice offering alternative viewpoints has deep relevance to the country even after a century. David Frawley has no hesitation in saying, “With due respect to Gandhi and his efforts, Sri Aurobindo provided a more profound Yogic view of India and a more powerful practical view of strength and leadership for the country.” However, the fact remains that independent India was harsh to Sri Aurobindo as the history books nearly obliterated him despite having played a huge role in the independence movement and the Indian renaissance of the early 20th century, along with the likes of Tagore and Vivekananda. The whitewashed history of freedom struggle was an injustice to the growing generations.

This two-part essay introduces only their political philosophies, as both have an extensive corpus of writings on many other issues.

SRI AUROBINDO: SCHOLAR, NATIONALIST, AND A YOGI

Sri Aurobindo, a vaguely known figure in the collective Indian psyche, simply vanished from all our teachings. An individual discovery opens up a whole new world of incredibly powerful writing. Aurobindo (born on August 15th, 1872), after his early education in Darjeeling, left for England at the age of seven years. He graduated from Cambridge University in 1890. He later passed a tough Indian Civil Service Exam but did not show up for a horse-riding test, and hence the examiners disqualified him! At the age of 21 years, in 1893, Aurobindo, back in India, joined the state service of Maharaja Gaekwad of Baroda where he taught English and French. Gradually, he became involved in the Revolutionary movement against the British. He used his extraordinary writing powers for a series of anti-colonial magazines like Indu Prakash, Bhawani Mandir, and Bande Mataram. In 1906, he shifted to Calcutta to become the Principal of the newly opened Bengal National College. He soon became the editor of Bande Mataram.

A major event in the history of India, not greatly stressed in our history books, was the partition of Bengal in 1905 on Hindu and Muslim identities by Lord Curzon, though the official reason given was ‘administrative convenience’. The infuriated people of Bengal rose and initiated a revolt based on the twin concepts of Boycott (of all British goods) and Swadeshi (encouraging indigenous produce only). The revolution grew organically across all parts of the state. This revolution thoroughly rattled the British. Initially confined to an economic boycott, it expanded to imbibe other principles like a National Education policy. It finally burst into the national scene (Punjab, Maharashtra, Madras, Gujarat) as a call for complete independence from the British. This foundation for a strong anti-British movement also culminated in a great Hindu-Muslim divide, thanks to a shameless governmental strategy of ‘divide and rule.’ The Nawab of Dacca was one such important person who initially stopped many Muslims from participating in the agitation against the British.

1905 is thus a landmark year that began both our path to independence and Pakistan-Bangladesh too. It also generated more extremist movements. The intellectual support came from people like Sri Aurobindo and Rabindranath Tagore. Bankim Chandra’s Bande Mataram became the reverberating clarion call for the masses. Sri Aurobindo, writing for Bande Mataram magazine, emphatically established the principles of this passive resistance. The British authorities arrested him for alleged seditious writings in 1907, but the judiciary released him for lack of evidence.

The Swadeshi Movement of Aurobindo and others had already laid the base for Indian Independence. Their Nationalist Party was with the Congress initially but broke away finally in the 1907 Surat session from the Moderates due to serious differences. The Nationalists charged the Moderates, led by leaders like Gopal Krishna Gokhale, of having an ineffective method of fighting for independence by way of ‘pleas, petitions, and prayers.’ Aurobindo’s arrest in the Alipore Bomb Case in 1908 and a year in jail was a life-changing experience for him. A deep spiritual experience transformed his life radically into another divine sphere. Continuous harassment by the Britishers forced him to flee and settle in the peace of French-ruled Pondicherry in 1910 where he continued to write extensively on various issues till his death in 1950.

SRI AUROBINDO’S DOCTRINE OF PASSIVE RESISTANCE

Sri Aurobindo called the Moderate Congress approach ‘the theory of opposition in words but co-operation in practice.’ He enunciated his program in clear terms: The Nationalist programme asserts autonomy as the right of all nations, advocates the use of every legitimate and peaceful means towards its establishment whether swift or gradual, and especially favours the use of self-help to train and organise the nation for self-government and of passive resistance to confirm and defend the measures of self-help and to bring pressure on the bureaucracy to yield a substantial measure of self-government.

Sri Aurobindo, in 1907, published in Bande Mataram a series of articles which presented the doctrine of ‘passive resistance’ or ‘defensive resistance’. He writes that there were only three possible policies for freedom: petitioning, a sure-to-fail way; self-development and self-help (which he advocated); and the orthodox historical method of organised resistance (which has a place when everything else fails). There was a colonial argument, and reiterated by many Indians too, right till independence, that India was unfit for self-rule unless its socio-economic-educational status improves. Answering such ideas, he writes, ‘Political freedom is the life-breath of a nation; to attempt social reform, educational reform, industrial expansion, the moral improvement of the race without aiming first and foremost at political freedom, is the very height of ignorance and futility…’

He demanded a free national Government unhampered even in the least degree by foreign control ruing that the Moderate politicians could not realize these elementary truths. He minced no words in his attacks on the Moderates led by Congress leaders like Gokhale and Pherozeshah Mehta. He writes, ‘Schooled by British patrons, trained to the fixed idea of English superiority and Indian inferiority, their imaginations could not embrace the idea of national liberty, and perhaps they did not even desire it at heart, preferring the comfortable ease which at that time still seemed possible in a servitude under British protection, to the struggles and sacrifices of a hard and difficult independence.’ He more than amply clarifies that the advocates of self-development and defensive resistance were no extremists and were trying to give the country its last chance of escaping the necessity of extremism.

Passive resistance was the only effective means by which the organized strength of the nation could gather under a powerful central authority and be guided by the principle of self-development and self-help, can wrest control of national life. Despite disliking violence, he writes that in countries like Russia and Ireland, where the denial of liberty was violent, the answer of violence to violence remains justified and inevitable. He writes, ‘… In other methods, a daring minority purchase with their blood the freedom of the millions; but for passive resistance it is necessary that all should share in the struggle and the privation.’

The aggressive resister positively harms the Government but the passive resister abstains from doing something by which he would be helping the Government. The passive method is especially suitable for countries where the Government depends, for the continuance of its administration, on the subject people. Swadeshi and expansion of indigenous industries (to allow industrial boycott); indigenous arbitration courts (to prevent the entry of alien courts of justice); indigenous schools imparting national education; and a system of self-protection and mutual protection of our own (to allow an executive boycott) were the key components of the Swadeshi program as crystallized by Sri Aurobindo. The refusal to pay taxes was a natural and logical, most emphatic, result of such passive resistance. Such an attack would either result in conciliation or other methods of repression, which, in fact, would give greater vitality and intensity to the opposition.

According to Sri Aurobindo, this Boycott, while not illegal, was far superior to the Moderate method of ‘prayer, petition, and protest’. Indians not accepting passive resistance were guilty of treason to the nation and Aurobindo explicitly demands a social boycott of such persons. He was not shy of allowing ‘active resistance’ to supplement it at the slightest notice. ‘… if passive resistance should turn out either not feasible or necessarily ineffectual under the conditions of this country, we should be the first to recognise that everything must be reconsidered and that the time for new men and new methods had arrived.’

Concluding the doctrine, Aurobindo says that there can be no consent to any relations with England less than that of equals in a confederacy: ‘…to strive for anything less than a strong and glorious freedom would be to insult the greatness of our past and the magnificent possibilities of our future.’ Aurobindo defines resistance as of many kinds: armed revolt; aggressive resistance short of armed revolt; or defensive resistance, whether passive or active. The circumstances of the country and the nature of the despotism from which it seeks to escape must determine the form of resistance. Aurobindo’s passive resistance never did preach the kind of non-violence that Gandhi practiced.

THE MORALITY OF BOYCOTT

Sri Aurobindo wrote another essay where he strongly critiques people who condemn aggressiveness. This article, though unpublished, became evidence against him in the Alipore Conspiracy Case (1908). Aurobindo writes, ‘The love which drives out hate is a divine quality of which only one man in a thousand is capable… Politics is concerned with masses of mankind and not with individuals. To ask masses of mankind to act as saints, to rise to the height of divine love and practise it in relation to their adversaries or oppressors is to ignore human nature… The Gita is the best answer to those who shrink from battle as a sin, and aggression as a lowering of morality.’

Boycott was not an act of hate but an act of aggression for the sake of self-preservation. Hinduism recognizes human nature and makes no such impossible demand. It sets one ideal for the saint, another for the man of action, a third for the trader, and a fourth for the serf: ‘Politics is the ideal of the Kshatriya, and the morality of the Kshatriya ought to govern our political actions. To impose in politics the Brahmanical duty of saintly sufferance is to preach varnasankara… Between nation and nation there is justice, partiality, chivalry, duty, but not love. All love is either individual or for the self in the race or for the self in mankind. It may exist between individuals of different races, but the love of one race for another is a thing foreign to Nature. When therefore the boycott, as declared by the Indian race against the British, is stigmatised for want of love, the charge is bad psychology as well as bad morality. It is interest warring against interest, and hatred is not really against the race, but against the adverse interest.’

Aurobindo makes it clear that violence may be inexpedient at a particular time, but the moral question does not arise. The argument that violence interferes with personal liberty involves a singular misunderstanding of the very nature of politics. He writes that the whole of politics was, in fact, interference with personal liberty. The right to prevent such interference as will injure the interests of the race is the fundamental law of society. From this point of view, the nation is only using its primary rights when it restrains the individual from buying or selling foreign goods. Thus, a social boycott may be justifiable, but not the burning or drowning of British goods (though not morally unjustifiable).

THE SOUTH AFRICAN GANDHIJI: INITIAL FORMULATIONS OF SATYAGRAHA

Gandhiji spent a considerable amount of time (1893 to 1914) in South Africa at a crucial point in its history. It was a typical colonial story of the Dutch (Boers) and the English fighting each other initially and then unitedly against the natives. It was home to more than a million ‘indentured’ Indians (who arrived as laborers after the abolition of slavery) and ‘Passenger Indians’ (traders and professionals traveling as British subjects). At stake in this colonial warfare were humans and rich land resources.

Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed (The South African Gandhi) detail the years when he first formulated and tried to put into practice the principles of Satyagraha. In 1903, Gandhi set up an ashram on a hundred-acre land at Phoenix (Natal) to start his ideas of simple living, collective work, and manual labor. In 1910, he set up the Tolstoy farm near Johannesburg (Transvaal). Around the time the First World War broke out, he made a return journey to India via England and finally reached Bombay to a grand welcome in 1915.

Gandhi’s core worldview of Satyagraha or ‘passive or nonviolent direct action’ evolved in South Africa. The standard narratives trace the intellectual origins of Satyagraha (satya, truth; graha, firmness) to European thinkers, his mother’s piety, and many Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist influences. However, European influences were probably more vital, say Desai and Vahed: Tolstoy (The Kingdom of God is Within You), William Salter (Ethical Religion), and Thoreau (An Essay on Civil Disobedience). The key idea of Satyagraha was winning over the enemy with love and self-suffering; defying unjust rules and accepting punishments that go along with them; and most importantly, without malice or physical violence against the rulers. The idea is to get rid of the injustice but not to unseat the men from power. The means always must be right.

CRYSTALLISATION OF THE DOCTRINE IN INDIA

Pyarelal Nayyar (Pilgrimage of Peace) gleaned from Gandhiji’s writings, a complete outline of Satyagraha in theory and practice and titled it “Quintessence of Satyagraha“. The fundamental idea of Ahimsa (non-violence) crystallizes in the introduction. Gandhiji says that every right of man has a corresponding duty. Thus, the remedy for resisting an attack upon rights is merely a matter of finding the corresponding duties, followed by remedies to vindicate the elementary equality. The supreme duty is Ahimsa (non-violence) and thus it is the ultimate means to reach the Truth and fight for our rights. Ahimsa, a Positive Virtue, means the greatest love and greatest charity. ‘I must apply the same rules to the wrong-doer who is my enemy or a stranger to me, as I would to my wrongdoing father or son.’

A nonviolent conflict leaves no rancor behind, and in the end, the enemy becomes a friend. Non-violence was the law of the human race and not merely a personal virtue that extends easily on a larger national and international scale. Its habitual practice could even take on the might of the Empire. Even children, young men, and women, or grown-up people, can wield non-violence provided they have ‘a living faith in the God of Love and have therefore equal love for all mankind.’ The non-co-operation is with methods and systems, never with men, and hence there should be ‘the keenest desire to cooperate on the slightest pretext even with the worst of opponents.’

The Ten Commandments of Satyagraha, as Pyarelal enumerates, are:

- Satyagraha is utter self-effacement, the greatest humility, the greatest patience, and the brightest faith.

- I must always allow my cards to be examined and re-examined at all times and make reparation if any error is discovered.

- Satyagraha must not be the result of anger or malice. It is never fussy, never impatient, never vociferous.

- A Satyagrahi may not even ascend to heaven on the wings of Satan.

- He must believe in truth and non-violence as his creed and therefore have faith in the inherent goodness of human nature, which he expects to evoke by his truth and love expressed through his suffering.

- A Satyagrahi never misses, can never miss, a chance to compromise on honorable terms. It is always assumed that in the event of failure, he is ever ready to offer battle.

- A Satyagrahi bids goodbye to fear. He is, therefore, never afraid of trusting the opponent.

- It is never the intention of a Satyagrahi to embarrass the wrong-doer. The Satyagrahi‘s object is to convert, not to coerce, the wrong-doer.

- The very nature of the science of Satyagraha precludes the student from seeing more than the step immediately in front of him.

- A Satyagrahi must never forget the distinction between evil and the evildoer. A Satyagrahi will always try to overcome evil by good, anger by love, untruth by truth, and himsa by ahimsa.

Civil Disobedience (a term coined by Thoreau as Gandhiji believed) is a civil breach of unmoral statutory enactments. Satyagraha consists at times in Civil Disobedience and other times in Civil Obedience. This disobedience to the law of the State becomes a peremptory duty when it comes in conflict with the law of God (He does not define what this law of God is). Civil Disobedience, though an inherent right of any citizen, never descends into anarchy. Non-co-operation excludes Civil Disobedience of the fierce type.

His views on the role of violence remained a bit confusing, however. He writes, ‘Non-violence is a virtue of the strong. However, if there is only a choice between cowardice and violence, I advise violence… Non-violence presupposes ability to strike. It is a conscious, deliberate restraint put upon one’s desire for vengeance …When you have failed to bring the error home to the law-giver by way of petitions and the like, the only remedy open to you…is to compel him by physical force to yield to you or by suffering in your own person by inviting the penalty for the breach of the law.’ Critics thought it was not very clear how affected citizens under the stiff hand of an alien bureaucracy could strike and yet practice non-violence to change the hearts of the rulers.

SATYAGRAHA IN PRACTICE: AMBIGUITIES AND CONTRADICTIONS

The British leaving the country because of Gandhian ahimsa is a story internalized by most people in India and abroad. But critics maintain that this simply puts a veil both on the role of other significant factors in gaining independence and on the brutalities inflicted by colonial rule. The story was convenient for the British as it made for an honorable exit even though they ripped our country apart at many levels. As Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed detail in their book, Gandhiji’s Satyagraha had plenty of problems.

In the Empire’s hour of need during the wars, Gandhiji showed a startling reversal of the general philosophical drift of Satyagraha and non-violence. Gandhiji himself acknowledges in 1920 (To Every Englishman in India), that no Indian had cooperated with the British government more than he had in twenty-nine years of public life instead of becoming a rebel. He writes that he put his life in peril four times for the empire: Boer War (1899) and the Zulu (Bhambatha) revolt (1906), where he raised the Ambulance Corps; the First World War (1914), where he similarly raised an Ambulance Corps but could not personally serve due to an attack of pleurisy; and finally, as a promise to Lord Chelmsford at the War Conference in Delhi (1918), when he went on a recruiting spree in the Kheda district.

Though some scholars have tried to rationalize Gandhiji’s loyalty to the Empire during the wars in South Africa, this was problematic. The major issues like the scorched earth policy of the British, the death of many Boers in the concentration camps, and the thousands of Africans who died of hunger and starvation did not seem to concern Gandhiji. Some scholars claim that Gandhiji took the suffering of Boer women and children in the concentration camps as a model for Satyagraha, which caused the English to relent. Desai and Vahed (The South African Gandhi) say that this is a remarkable delinking from actual historical circumstances.

Gandhiji would define Satyagraha, refine it, and authorize its practice. His definition of victory was fluid; it could be in the actual performance of Satyagraha even when the goals failed many times. He always blamed any act of violence on ‘the mob’ who were “susceptible to manipulation by mischief as they were open to enlightened leadership.’ Satyagraha was also not immune to racial stereotyping. Only the Indians who have ‘drunk the nectar of devotion’ could lead the people on the right path of Satyagraha. Gandhiji was clear on the racial hierarchy of the Indians over the native Africans. Gandhiji rarely spoke about African issues and their right to independence. His involvement for Indian rights was also largely unsuccessful or weakly so, with huge compromises, basically accepting a second-rate status for Indians.

A letter to Hitler in a naïve bid to change his heart; asking the British to peacefully accept its conquering by Germany; asking the Jews to accept killing by the anti-Semites as a supreme act of non-violence; and asking Hindu refugees to return to Pakistan even at the risk of death was a controversial example of his peculiar non-violence application. One of the serious criticisms of Gandhiji was that his non-violence was a weapon to the liking of his opponents. His power and hold over the Congress and the masses did neutralize the call of those who sought to use more revolutionary methods to advance Home Rule. In the 1913 strike in South Africa or later in 1922 (Chauri-Chaura incident) during the post-Jallianwala Bagh non-cooperation call, Gandhiji would suddenly call off the movement with incidents of violence on the part of the rioting mobs. Non-violence as a tool was just perfect for them as many English officials admitted in private.

Gandhiji pointed out that civil disobedience could be for the redress of a local wrong; to arouse the consciousness of the local people; or in a particular issue like salt or freedom of speech. It could never be in general terms, such as independence. A striking example was organizing a strike in Bombay in support of a brave journalist, Horniman, who was deported forcibly for reporting the Jallianwala Bagh massacre to the world. Based on the principles of Satyagraha, he decides that the coming Sunday should be a combination of a hartal (strike) restricted only to Bombay; fasting for 24 hours; and private religious devotion in every home with their respective scriptures. Gandhiji exhorts that the hartal or strike would be such that there should be no stoppage of business, no large public meeting of protests, no processions, and no violence of any kind whatsoever! Gandhiji’s most succinct principle of Satyagraha: hatred ever kills, love never dies.

How effective was Satyagraha? Gandhiji launched many mass movements, starting from the Rowlatt Act Satyagraha in 1919, the Non-Co-operation movement of 1920-21, the Civil Disobedience Movement of 1930-31, and the Quit India movement of 1942. A historical reading clearly shows that none of them proved effective. Our independence had perhaps far more important reasons: the disastrous post-war English economic collapse; the naval mutinies; Subhash Bose; and a friendlier (perhaps more sensible) Labour Government in England.

The supporters of Sri Aurobindo, like the latter himself, maintain that Gandhi simply carried the Swadeshi movement forward. The Swadeshi movement was both idealistic and more practical in its aims and methods. The Swadeshi movement severely undermined Moderate reformist politics and brought revolutionary movements to the fore. Sri Aurobindo may have been sympathetic to their movements, but he never supported them openly, despite all efforts by the British to show that he did. It laid the foundations of an Industrial India and an agricultural India. Gandhiji carried forward ideas for the development of agriculture and a peasant-based economy, expressing a general dissatisfaction with technology and modernization. The Swadeshi movement did bring the educated middle class and the commercial classes into the political field, previously restricted to only an elite few in the Moderate kind of politics. As one author says, ‘It (Swadeshi) laid down a method of agitation which Gandhi took up and continued with three or four startling additions, khaddar, Hinduism, Satyagraha – getting beaten with joy, Khilafat, Harijan, etc. With the departure of Sri Aurobindo to Pondicherry and the imprisonment of Tilak, the second phase of the Freedom Struggle ended.’

In the next part, we shall see how the two great figures interpreted the Gita and the Indian scriptures and what they thought of each other. It is an amazing fact of their lives that the two towering personalities living in contemporary times never met each other in person!

Leave a Reply