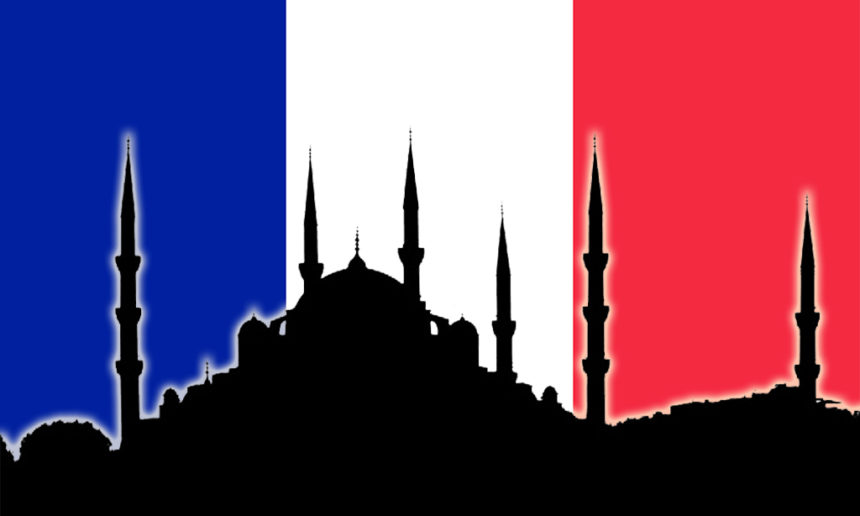

The French hold liberal views about most things in life including religion, are secular and love to discuss Sartre and Camus. This time when I spoke to them, it was different. The mood, the tone was not what I had experienced in a long time

Why are the French angry?

I have several French friends. They are philosophers and psychologists who live and work in France. They are acutely aware of the crisis facing their society and when psychologists listen to people who share with them their existential angst, they deeply feel the pulse of that society. Like most French intellectuals they get into discussions and analyze philosophy, poetry and politics. They hold liberal views about most things in life including religion, are secular and love to discuss Sartre and Camus. This time when I spoke to them, it was different. The mood, the tone was not what I had experienced in a long time.

It was with one of them that I was talking about the crisis in France. She is a psychologist and works with refugees, those seeking asylum. “France has changed forever,” she was saying, “and we are not going back to where were earlier. This time the attack, the beheading and the terrorist attack has changed us permanently and this time we all feel it collectively. If this beheading had taken place a decade ago, many of us would have walked away, shrugged our shoulders, rationalized it by saying ‘it was an act of individual aberration, the violence by a mad fanatic, a crazy fellow who does not represent his true faith’. Not any longer. No one in France is saying that now. Today, we see the ‘beheader’ not as a deviant personality and acting alone anymore. We realize he has the support of his entire people, his faith, his book and a message that is directed at all of us. Even the Charlie Hebdo massacre was seen as an aberrant act, a deviant psychopathological act of a religious fanatic by many Frenchmen, including me. That has changed now.”

“What do you see the present act as then?” I asked her. After a moment’s silence, she added, “The present act of beheading is seen by French as part of a mission, one that belongs to a larger whole that cannot be explained by individual culpability. The act strikes at the core of what it means to be French, the French nation and to have a French identity. To preserve it is the responsibility of all Frenchmen.”

“Why did the act of beheading and the terror attack in the church take on such a different turn?” I was wondering. “Why has this change come about in a people who not so long ago were considered the poster boys of liberalism, the most tolerant?”

My friend answered, “It has come about because we see that acts like beheading are an attempt, are seen as a victory over us, over French values and the support it is receiving from all over the world. We see people celebrating this violence on a Frenchman in our own country and the world and justifying it by saying this is a way of life we must accept and coexist with. That has struck at the core of our understanding of all the single attacks, as an assault on French identity.”

“Wasn’t this celebratory mood present earlier?” I asked.

“The French people lived in denial and didn’t know,” she said.

“What do you see the mission as that you described?” I asked.

“The individual act of beheading is a mission that gives sense, direction, excitement and urgency to life for a whole faith to dominate us. It is no longer a meaningless act by a lunatic mad man.”

I shared the time when Kashmiri Pandits were driven out of their homes thirty years ago by loud slogans to convert or leave or die and the sense of celebration that had erupted in the people. Then too many in India had described it as a fringe, an aberration act. “I can relate to that,” she said and added, “it is at such times you realize how wrong you were and why such individual acts are representative of a larger mission. The French have given the world the Bastille, the ideas of liberty, fraternity and equality. It is rooted in our blood. The last time it arose was during the German occupation of our country. Many of the people I talk to now describe the present crisis in the same language. They describe it similar to an occupation, an attack on us. We now see that we have a struggle ahead of us that is our creation due to our naivety. Either we give in and lose everything or fight back. We have chosen the latter.”

“Why has this change come about in French society now?”

“For too long we were riddled with guilt over our Algerian experience, our colonial legacy and the existentialism that arose. Similar to Germans who were riddled with the guilt of the holocaust, we were taught to atone for our ‘sins’. No longer so. We don’t see that we need to do so anymore. In trying to redeem one injustice, we are in the process of creating another for our children.”

“What is making the French create a direct confrontation with the present crisis of terror? It is unlike the way any other society responds.”

“To understand that you have to understand the French persona and its connection to existentialism. Existentialism is the belief that we must confront our reality directly and not through false pretences. That we must analyze and confront the human condition and its hypocrisy directly and openly to lay bare its contradiction and complexity. This is what the French believe in perhaps like no other society. There are no underlying motives, no political correctness that lie at the confrontation of the reality of existence. The rebel in a Frenchman is innate and comes from not allowing ourselves to be carried along with the flow of existence but confronting it by stepping outside, by making conscious decisions. It is at that moment when man begins to exist as man and this is what this present struggle will lead us to,” she added with a sigh.

“Has the French society then given up the idea of assimilation with its minorities?” I asked.

“You may say that,” she said. “We never thought of it but if we don’t do it now, then we are on the verge of losing our identity. We are a troubled, a wounded society and one that can get closure through courage, by facing it head-on, by realizing that we are caught up in a civilizational conflict by each attack. Maybe that is why we are the first in the world to respond.”

Will the rest of the world follow the French example? Will other societies follow in the footsteps of the French? As another French author, Victor Hugo, said it not so long ago, “It is impossible for any army to stop the tide of an idea whose time has come.” I believe this sentence may sum up the present French crisis.

Leave a Reply