The sacred land of Bengal was polluted for the first time when Bakhtiyar Khilji invaded Bengal during the reign of Lakshmana Sen in the 13th century. This paved the way for the easy spread of Islam in the region. The land of Kali was now thronged with Islamic missionaries from West Asia. One among them was Sheikh Awal, an Arab missionary who came from Baghdad, Iraq to preach Islam in India. The date of Awal’s arrival is contested as different records suggest different timelines of his arrival: some say that he came with Hazrat Bayazid Bostami, a 9th-century Sunni preacher1, however, this claim is rejected by the national encyclopedia of Bangladesh.2

Awal had a clear plan: he had come to preach Islam and had no intention of settling in India. While he eventually went back to Iraq, he left his son, Sheikh Zahiruddin, in India, whose generations continue to live in the subcontinent to this day. The Sheikhs settled in Tungipara in the Gopalganj district of Bengal. Although the Sheikhs were in a constant state of clash with the Kazis3, the descendants of the Sheikh family had matrimonial ties with the Arab-origin Kazi and Khondokar families.

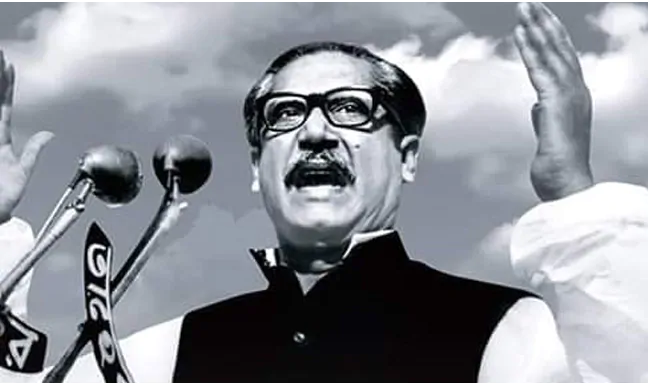

The Sheikhs also married among themselves. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the first Prime Minister of Bangladesh, was born out of one such incestuous marriage between Sheikh Lutfur Rahman and Sahera Khatun. While Lutfur Rahman was Sheikh Jan Mahmud’s great-great-grandson, Sahera Khatun was his granddaughter. He was married at the age of 13 and, not deviating much from the Sheikh family’s history of incestuous marital relations, he was married to his paternal cousin Sheikh Fazilatunnesa, also known as Renu, who was just three years old.4

Mujib had to withdraw from school in seventh grade because of glaucoma (a group of eye conditions that damage the optic nerve), probably congenital, which is common in the offspring of incestuous marriages.5 He could only return to school four years later. Given his late admission and being older than the other students in his class, he turned out to be an absolute bully. As he writes in his memoir, “I was older than most boys in my class because of the four years I had lost due to my illness. I was a very obstinate boy. I had my own gang of boys. I would mercilessly punish anyone who offended me. I would fight a lot.”6 He was also involved in the extortion of money in the name of the “Muslim Welfare Association”, which was founded by his tutor, Kazi Abdul Hamid.7

Mujib had very strong anti-Hindu sentiments from a young age, which intensified even more after he met Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy. Suhrawardy had been involved in communal politics since the 1926 Kolkata riots, at a time when he was the Deputy Mayor. He noticed Mujib’s communal talent quite early, for he knew that he would need such radical young minds in the League to further its communal agenda.

Within weeks of meeting Suhrawardy, Mujib got involved in a criminal act. In order to rescue one Abdul Malek, who was allegedly being held inside, he broke into the house of local Hindu Mahasabha leader Suren Banerjee and assaulted the residents with his gang of boys. Though Mujib was detained for a week after being charged with murder, looting, and communal rioting, his political connections with Suhrawardy helped him secure an easy release.8

Mujib was hardly a good student. He passed his matriculation at the age of 22, that too after two attempts. He probably knew he wouldn’t be able to secure a job for himself, hence he entered politics at a very early age. He admired Fazlul Haq. However, he was unhappy that Haq had joined with a Hindu leader, Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, to form the first and only Hindu-Muslim unity government, popularly known as the ‘Shyama-Haq’ ministry.

Mujib vehemently opposed Haq’s decision of sharing power with Hindus. This was the first full-fledged political campaign under Mujib’s leadership. Interestingly, he had to stop targeting Haq when a lot of Muslims started criticizing him (Mujib). Given the unmatched popularity of Haq among the Muslims of Bengal, his father too had cautioned him against being hostile towards Haq.9 However, Mujib was never in favor of sharing power with the Hindus, and he always wanted Muslim domination of power in Bengal.

After finishing his matriculation, Mujib, during his Islamia College days in Calcutta, got seriously involved in politics and further increased his participation in the activities of the Muslim League. Due to his radical Islamic ideas and skills in manipulation, he became a famous name in college, especially among Muslim students.

During the premiership of his mentor, H.S. Suhrawardy, Bengal was hit by one of the worst famines of the 20th century. Suhrawardy was facing criticism from every corner of the state, including Muslims, for mass mismanagement. So, to divert Muslim attention away from the mismanagement of the famine, he organized “The South Bengal Conference for Pakistan” in Faridpur, ensuring that his leader would not be associated with any negative connotations among Muslims.10

The election of 1946 was a referendum on whether Pakistan would be formed or not, in which the Muslim League succeeded in forming a government in Bengal under Suhrawardy. Following the declaration of Direct Action Day on 16th August 1946, on the orders of Abul Hashim, general secretary of Bengal Muslim League, Mujib and his boys took to the streets of Calcutta to campaign for Pakistan. Mujib himself took on the task of organizing Muslim students in Calcutta by 10 a.m. at Islamia College and then leading them to the afternoon rally at the Calcutta Maidan.

Meanwhile, Mujib rode his bicycle to Calcutta University and raised the Muslim League flag at 7:00 a.m.11. As Gramsci said, to rule, you need to first establish a cultural hegemony (i.e., control over education, the media, etc.). As Calcutta University represented Bengali excellence in research and education, Mujib’s hoisting of the League’s flag sent a stern message of the consolidation of the League’s communal agenda. For years, Bengal’s Muslim leadership made rigorous attempts, though unsuccessful,- most notably through the Secondary Education Bill (1940)12– to wrest control of the education system from what they considered Bengali Hindu dominance.

The Muslim mobs and Muslim National Guards (a quasi-military organization affiliated with the Muslim League) were wreaking havoc on Hindus, aided by the police (recruitment of Punjabi Muslims in large numbers was made with immediate effect by Suhrawardy in the Bengal police).13 Mujib was again leading from the front as he had expertise in the use of guns. He also led a mob that attacked the Hindus with bricks and stones. He writes about the incident, saying, “A few of us immediately cried out, “Pakistan Zindabad.” In no time at all, our numbers swelled. By this time, the Hindu mob had reached us. We had no option but to resist them. We picked up whatever bricks or stones we could find and started to attack them.”14

The intentions of the Muslims under Suhrawardy were crystal clear, i.e., to kill the Hindus en masse to give Calcutta a Muslim majority, so that it could be easier to claim it for Pakistan.15 However, Hindus as a community fought back valiantly under the leadership of Gopal Mukherjee (famously known as Gopal “Patha”), and inflicted heavy damage to the Muslim side. Mujib, witnessing a large number of casualties on his side, sought a truce and pleaded before Gopal with folded hands to end the carnage. Gopal accepted their complete surrender on the condition that the Muslim League reciprocate the same.16

However, Mujib was a true Muslim who saw Syed Ahmed Barelvi’s Wahabi Movement as a justified rebellion and took pride in the fact that thousands of Muslim jihadists from Bengal marched barefoot to Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. He believed Pakistan was a just demand for the emancipation of India’s Muslims, who were oppressed by Hindu landlords and moneylenders.17

Mujib identified himself with Muslim invaders and could never accept that he pleaded against a malaun (Bengali word for kafirs). So when he narrates Direct Action Day, he gives an altogether different account of the event. According to him, Hindus started the violence, and the otherwise violence committed by Muslims was only reactionary. Contrary to all the primary sources, he writes, “On 16 August, the Muslims taken a beating. The next two days, the Muslims beat up the Hindus mercilessly.”18

Mujib’s politics and his thought process were rooted in his anti-Hindu Islamic ideology. He was a Muslim first and used the Bengali language only as a tool to gain territory to rule over. In his final years, Mujib largely abandoned his trademark “Joy Bangla” salutation in favor of “Khuda Hafez”, a greeting preferred by Muslims. He never wanted a separate Bengali nation, he just wanted his share.19 Abdul Mu’min Chowdhry, a Pakistani author, notes that with his “courted arrest”, Mujib made a gentleman’s agreement with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to keep Bangladesh within a confederated Pakistan.20

Today, Bengali culture hardly has anything indigenous or ancient about it. The majority of the Bengali speakers are Muslims, and it is made to appear that there is no difference between Bengali identity and Muslim identity. The formation of Bangladesh has been a major step toward the creation of this narrative and the appropriation of Bengali culture.

The Hindus of Bangladesh, who had voted for the Awami League and Mujib, got nothing as Mujib never changed. He neither recognized the contribution of Hindus in Bangladesh’s liberation nor did he even recognize the Hindu Genocide of 1971. He wanted his country to be more Islamic than West Pakistan.

In his homecoming address on 10th January1972, Mujib reminded everyone of the new state of Bangladesh’s Islamic and Muslim quotient, saying, “Let everyone be informed that now Bangladesh stands as the world’s second largest Muslim state, and Pakistan’s position is fourth…[in terms of Muslim population].”21 Mujib made this statement intentionally because he didn’t want to dilute his Islamic image.

His actions after coming to power, like banning anti-Islamic activities like the sale of alcohol and gambling, speak for themselves. He also established the Islamic Foundation to institutionalize the spread of Islam, whereas when it came to Hindus, he continued the draconian Enemy Property Act, which took the properties of Hindus, considering them enemies of the nation, with the name of the Vested Property Act.22 He bulldozed the remnants of the Ramna Kali temple and handed the property over to the Dhaka Club to add salt to their wounds.23

There are a lot of whys that can be asked at the end, like, why is the anecdote of “Bangabandhu”, or friend of Bengal, being used for someone who actively played a part in the destruction of Bengal and its culture? Why is a man, who was responsible for the killing of indigenous Bengali Hindus, referred to as the “Greatest Bengali of All Time”24? Why is an average statesman, who started his career as a ragtag student leader of a fascist party, given near-saintly larger-than-life status? The answers to these questions are difficult as they can make both the Bangladeshi and the Indian governments, extremely uncomfortable.

References

1.Chowdury, S. R. (2019). Foundation of Religious Liberalism in Bangladesh: Contribution of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Awami League. International Journal of Social, Political and Economic Research

2. Karim, A. (2012). Banglapedia: The National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved from http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Bayejid_Bostami

3.Rahman, S. M. (2012). The Unfinished Memoirs. Penguin.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7.Ibid.

8.Ibid.

9.Ibid.

10.Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Chattopadhyay, R. (1994). Higher Education in Bengal (1919-47): A Study Of It’s Administration And Management (Volume 1). Bethune College, History. Kolkata: University of Calcutta.

13. .Rahman, S. M. (2012). The Unfinished Memoirs. Penguin.

14. Ibid.

15. Mazumdar, J. (2017). ‘The Butcher Of Bengal’ And His Role In Direct Action Day. Swarajya. Retrieve from

16. Mazumdar, J. (2017). Remembering Gopal Mukherjee, The Braveheart Who Saved Calcutta In 1946. Swarajya. Retrieved from

17. .Rahman, S. M. (2012). The Unfinished Memoirs. Penguin.

18. Ibid.

19. Garry.J. Bass. (2013), Blood Telegram

20.Chowdhry, Abdul Mu’min (1996). Behind the Myth of 3 Million by Abdul Mu’min Chowdhry.

21. Hussain, S.A. (2022). Bangabandhu and Islam. Daily Sun. Retrieved from

https://www.daily-sun.com/printversion/details/614022/Bangabandhu-and-Islam

22. Dastidar, S.G. (2021). Bengal’s Hindu Holocaust

23. Ibid.

24. Mustafa, S. (2004). Listeners name ‘greatest Bengali’. London: BBC. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/3623345.stm

Leave a Reply