In the previous parts (1 and 2), we saw the overall understanding of political systems in the Western world and the political trajectory of post-independent India, primarily determined by Jawaharlal Nehru, who was the Prime Minister of the country uninterruptedly from 1947 until his death in 1964.

In this part, we shall look at the most famous ancient political text in India, which had some great insights into political organisation. Dharma was the basis of all Indian activity in any field, and there was never a proper understanding of this despite repeated stress by some prominent modern thinkers like Sri Aurobindo and Ananda Coomaraswamy. In contemporary times, SN Balagangadhara and the Ghent School are giving some important insights into the nature of traditional Indian political discourses.

Kautilya’s Arthashastra and Others

Kautilya’s Arthashastra (2nd century BCE to 3rd century CE), influential till the 12th century CE, was a solid political treatise (six thousand shlokas, one hundred and fifty chapters, and fifteen books) covering almost all aspects of ruling a kingdom. The text makes explicit the four sciences in society from which everything concerning righteousness and wealth derives: Anvikshaki (the philosophies of Sankhya, Yoga, and materialism); Trayi (the triple Vedas); Varta (agriculture, cattle breeding, and trade); and Danda-Niti (the science of government).

Philosophy, or Anvikshaki, gives light to all kinds of knowledge; the Vedas teach about righteous and unrighteous acts (Dharmadharmau); and the Varta about wealth and non-wealth. These, in turn, depend for their well-being on the science of government, which alone can procure the safety and security of life. It says that the sciences should be under the authority of specialist teachers, while theoretical and practical politicians should teach Danda-Niti.

Arthashastra details the obligations of each of the four varnas and the four ashramas—Brahmacharya (student), Grihastha (householder), Vanaprastha (retired), and Sannyasa (renunciate)—of a domestic-spiritual life, a basis for a well-ordered and harmonious society. The overarching framework for these varnas and ashramas are the four purusharthas (purposes): dharma (morality), artha (wealth), kama (desires), and moksha (enlightenment). Harmlessness, truthfulness, purity, freedom from spite, abstinence from cruelty, and forgiveness are duties common to all.

The king should never allow people to swerve from their duties. The ideal prince learns military arts, Itihasa, Purana, Itivritta (history), Akhyayika (tales), Udaharana (illustrative stories), Dharmasastra, and Arthasastra from disciplined teachers. The well-educated king, devoted to the good governance of his subjects and bent on doing good to all people, will enjoy the earth unopposed, declares the treatise. Arthashastra is a prototypical example of the textual material of India, laying out the ideal and practical aspects of administration and the behaviour of kings, citizens, and governments to the finest detail. The organisation of the government departments, the method of revenue collection, the restrictions on illegal trade, the method of choosing the kings and key administrative officers, the rules of agriculture, the encouragement of artisans, and so on are in such excruciating detail that one could as well develop the treatise for contemporary times.

Among the many texts like the Ramayana, Mahabharata (especially the Shanti Parva), and Tirukkural, the focus has been on duties rather than rights for both the rulers and the ruled. Dharma, though difficult to translate, definitely not implying religion, is, in its broadest possible scope, the maintenance of cosmic order. Each sentient being has a duty, according to his station in life, to maintain that order. Hence, the interpretation of dharma in the Indian context has always been about duties rather than rights, a situation opposite to the Western ideas of individualism and rights. The consistent theme of our scriptures and texts is to describe and ensure an enlightened monarchy. Our political philosophy has been radically different from the rights-based approach of most liberal democracies.

Interestingly, ancient India (Saptanga tattva in Manusamhita or Sapta–prakriti in Kautilaya’s Arthashastra) conceptualised the nation-state as comprising seven-fold organs: Swami, or King or sovereign ruler; Amatya (Ministers); Janapada (country or region or province and its residents); Durga (secured fort or town or Capital); Kosh (treasury); Danda (punishment to the criminals); and Mitra (group of different faithful nations and kings). In Sukraniti, another Indian manuscript, there is a similar seven-fold ‘organic theory’ of the nation-state: King is the head; Minister is the eye; Mitra, or friend, is like the ear; Danda, or punishment process, is the power; Kosh is the mouth; Durga, or secured town or capital, is the hand; and Janapada is like the leg of the nation.

The overwhelming Indian model was thus an enlightened monarchy, decentralised units, and free citizens who could cross the borders without attracting charges of treason. The citizens of Bharat had a deep cultural and spiritual bond that gave them unity despite enormous diversities in customs and languages. Undoubtedly, there were wars and battles, but on some principles, like never attacking the common citizens or destroying temples or agricultural lands. Taking slaves from the defeated land was unknown.

Dharma in Indic Political Philosophy

Our foundational texts emphasise the four core human values: Dharma (right living), Artha, Kama, and Moksha. This diverges from the Western rights-based individualistic philosophy. The pursuits of Kama (passion or desires) and Artha (political or economic wellness) are always acceptable if they base themselves upon dharmic values of harmony of the individual with society. The goal always remains moksha, or enlightenment, in all human endeavours — the release from bondage to complete freedom.

As Jaithirth Rao (The Indian Conservative) explicates, Dharma has three important ideas: Charitra, Raja, and Sukshma. Charitra, the character of individuals and groups, focuses on peace, harmony, and mutual trust. Raja Dharma (appropriate royal conduct), predating Magna Carta by centuries in suggesting that the sovereign is not above the law, promotes the happiness of the subjects as a protecting and non-predatory state. Sukshma Dharma comes into play when conflicting actions appear equally virtuous. Yuga Dharma, an idea going back some 2500 years (Apastamba Sutra of the Yajur Veda), suggests that each time period requires different dharmic responses from the virtuous. Apad Dharma is dharma-modifying during times of stress and war. Our traditions thought of almost all situations and the dharma of such times.

The Atharva Veda and the Isavasya Upanishad want us as trustees responsible for our possessions — the inherited land, ideas, culture, arts, thoughts, and philosophies — to pass on in an intact or better state to our descendants. In the economic field, texts like Tirukkural and persistent Indian institutions (the mandi and the bazaar) favoured free markets, says Jaithirth Rao. In traditional Hindu kingdoms, the polity and the social order were inseparable.

The king’s dharma consisted of preserving and enforcing the varna and jati-based social structures. Neither the modern concept of democracy nor its parliamentary articulation have a parallel in Indian thought. Karma determined an individual’s birth and natural endowments and thus fully deserved them; the modern notion of ‘group justice’ has no analogy in much of Hindu thought. In the Hindu theory of Purusharthas, several constraints surrounding the acquisition of artha could not form the basis of modern industrial society, as Bankim Chatterjee skillfully showed in his Samya, says Jaithirth Rao.

The king’s belief systems could be independent of those of his citizens, an impossibility in Western monarchies. A citizen could cross kingdoms without charges of treason, and there was no concept of slavery as ‘a person ruling over another’ in Indian culture, says Dr. SN Balagangadhara. Though contemporary scholars might try to torture our texts and Vedas to find evidence of slavery, it was non-existent, as was true in the West, which has a deep and troubling history of slavery.

Indic political philosophy has been consistently conservative in nature. Organic evolution, rather than a radical revolution, was the basis of change. Sanatana (Eternal) Dharma is harmony, starting from the individual self to encompass wider areas of family, society, and the state. Dharma ultimately talks of balance and harmony with not only fellow humans but animals, non-living objects, and the environment around them. The principles of feminism, ecologism, humanity, and acceptance of diversity intricately permeate through our best philosophical traditions. Giving a separate voice to these issues makes us distinctly uncomfortable, as it presupposes that Indians never thought about them.

Modern Indian Thinkers: Sri Aurobindo

Sri Aurobindo was one of the most profound thinkers of modern India and wrote extensively on all matters concerning India. He was critical of the Westminster model of parliamentary party-based governments and said it was unsuitable for India. Like Tagore, Sri Aurobindo was uncomfortable with the European idea of the nation-state, which he thought was only a forced political unity that was fragile in nature. The risk of such nation-states and their consequent nationalism was obvious in the colonial expansions and the world wars. For Aurobindo, political unification was secondary to another deeper form of unity already existing in India.

Sri Aurobindo understood a nation as a true unity instead of an empire, which is a political unity. Political unity is utterly destructible. A nation, on the lines defined by Sri Aurobindo, on the contrary, is considered to be the “living group-unit of humanity,” from which we can emerge into internationalism too. In The Ideal of Human Unity (The Ancient Cycle of Prenational Empire-Building), Sri Aurobindo details the development of nations in cycles. In the first cycle, a local unit overshoots the regional and national units to become an imperial body. There is a forcible unity among other local units. The second cycle has three successive intermediate stages: a) feudalism; b) the grip of absolute sovereign authority, namely the King; and c) finally, the Church. The third cycle tends to be representative of the ‘whole conscious,’ be it individual or community, which absorbs all. This has strong roots in the minds of its citizens.

Through decentralisation, the subordinate parts tend to merge into a stronger nation. Sri Aurobindo proposes the apex system of nation-building: nation (Rastra), state (Rajya), province (Pradesh), village (Gram). Like Gandhiji, he saw the village as central to nation-building. It was the basic unit of the nation, like the human cell is to the whole body. Gandhiji, however, placed villages as an independent unit with other units like districts, provinces, and the nation as larger circles surrounding the inner one. Sri Aurobindo’s model was an apex system where there was an independent yet dependent organic relationship between the primary unit and the higher organisations of complexity.

For Sri Aurobindo, spirituality of a high kind united India into a nation, and this spirituality was the basis of any Indian field like arts, literature, music, dance, drama, sciences, economics, social life, and politics. The spiritual message of India was the greatest message for the whole world suffering from strife and friction. For him, the Self (or the Brahman of Advaita) in all was the true basis for the unity of all individuals in the nation. India has had that message since ancient times. The spiritual message would be the basis for true internationalism too.

Consistently critical of politicians and political parties, he offered a decentralised polity with “one Rashtrapati at the top with considerable powers so as to secure continuity of policy, and an assembly representative of the nation. The provinces will combine into a federation united at the top, leaving ample scope for local bodies to make laws according to their local problems… Western polity conceives of doing away with political parties and creating governments of national unity only in times of war or crisis; India, because of her long tradition of a unity underlying her diversity, should have shown that unity is not a freak phenomenon but a workable basis for new politics.”

Following independence, India’s attempt at decolonization was less than half-hearted. As Michel Danino says, its apparatus remained wedded to a British constitution, a British polity, a British judiciary, a British administration, and a British educational system—a prison that is about the antithesis of what Sri Aurobindo envisioned.

Secularism would have made no sense to Aurobindo, who says, “Hinduism has left out no part of life as a thing secular and foreign to the religious and spiritual life… My idea of spirituality has nothing to do with ascetic withdrawal, contempt, or disgust for secular things. There is to me nothing secular; all human activity is for me a thing to be included in a complete spiritual life.”

Regarding caste, he says, “There is no doubt that the institution of caste degenerated. It ceased to be determined by spiritual qualifications, which, once essential, have now come to be subordinate and even immaterial, and is determined by the purely material tests of occupation and birth. By this change, it has set itself against the fundamental tendency of Hinduism, which is to insist on the spiritual and subordinate the material, and thus lost most of its meaning.”

Michel Danino says that Sri Aurobindo would therefore certainly not have approved of the clumsy caste-based reservation system, as far as it has hardened caste differences, triggered a race to backwardness, encouraged mediocrity by compromising on academic and bureaucratic standards, and failed to uplift the weakest members of society.

Regarding the economy, he was in favour of a social democracy but was critical of the socialist way of critiquing the capitalists. He described the capitalist class as a source of national wealth that needed encouragement to spend for the nation. “Taxing is all right, but you must increase production, start new industries, and also raise the standard of living; without that, if you increase the taxes, there will be a state of depression.”

Thus, like in his assessment of Indian culture, its past, and its future, Sri Aurobindo consistently looks at the spiritual essence of all living activities. Politics was no different. For him, individual and collective returns to the spiritual essence were the basis for human unity. A material route to achieving unity would always be fragile and temporary. Summing up Sri Aurobindo’s political vision for India, Danino says that it was to move away from party politics, aim at simplification, decentralisation, local empowerment, true participation, ruthless transparency, and a suppleness that remains responsive to evolving situations. Other institutions, such as the judiciary or bureaucracy, the penal system, and policing, would necessarily be part of this change, and their unwieldy structures, a source of misery rather than service to the common Indian, would have to undergo a major overhaul. Post-independent India sadly ignored him.

Ananda Coomaraswamy on Indian Political and Social Systems

Ananda Coomaraswamy (1877–1947), a geologist, art historian, cultural studies specialist, and philosopher, was a Sri Lankan Tamil who had a deep understanding of Indian culture. Coomaraswamy’s books and essays make for compelling reading to truly understand the past of India from a traditional point of view. He categorically rejected many of the flawed Western narratives regarding the East based on the values of modernity. India urgently needs to rediscover Coomaraswamy because many of his thoughts are as relevant as ever and can form the basis for many contemporary solutions. Our fascination with industrialization and modernity leads us on a path of increasing strife, as he and his like-minded philosophers like René Guenon constantly warned.

Importantly, he was critical of the English language as a medium of instruction, just like Sri Aurobindo. The latter’s National Education Programme insisted on education in native languages. Coomaraswamy says, “A single generation of English education suffices to break the threads of tradition and to create a nondescript and superficial being deprived of all roots—a sort of intellectual pariah who does not belong to the East or the West, the past or the future. The greatest danger for India is the loss of her spiritual integrity. Of all Indian problems, the educational is the most difficult and most tragic.”

In one of his important essays, The Bugbear of Democracy, Freedom and Equality, he explains that the ultimate values of Indian culture—the four purushartas (Dharma, Artha, Kama, and especially Moksha, or liberation)—form the bedrock foundation of all Indian social and political systems. These values form the principles of governing the country when the king is not a ‘ruler’ of the people of the country but an upholder of a larger entity called dharma in close coordination with the priestly community. Thus, secularism, which is the separation of the Church from the state, is a complete antithesis to the Indian idea of combining the equivalent two (the spiritual and the temporal, or the priest and the king) for a governing model.

There was a deep intertwining of the ‘spiritual’ (alaukika) and the ‘temporal’ (laukika) in traditional India, and this kept both the king and the priest in check by the other so as not to descend into tyranny. “…if the Regnum acts on its own initiative, unadvised by the Sacerdotium, it will not be Law, but only regulations that it promulgates.” Thus, like for Sri Aurobindo, in a culture where the ‘secular’ and ‘religious’ differentiation is meaningless and where every form of art, literature, poetry, dance, and even the sciences is an expression of the spirit or the one single Self, the concept of secularism does not make sense. Unfortunately, the secularism that guided Indian political thinkers after independence was an assault on the culture of India.

Coomaraswamy rejects the Western criticisms of the Indian caste system by saying that one needs to explain it and not be apologetic about it. He writes of the varnas and jatis, just like Sri Aurobindo, as a big cementing glue that prevented India from collapsing under the impact of extremely hostile attacks from across its borders. He realises the superimposition of the Western word ‘caste’ on the Indian social systems, and as a first point of difference, he says that the varna-jatis are not a class system as understood by the West. He found many parallels between Indian systems and the Platonic conception of societies and principles of justice.

He says, “The caste system — the alleged “hierarchical” system — is every man’s Way to realise the Last End — knowing his Self.” The varnas-jatis had deeply embedded principles of svadharma and svakarma (working according to one’s nature broadly). Such understandings of their own birth, individual nature, and the nature of work, combined with the idea of ‘desireless action’ could potentially lead each to the final moksha, or liberation. Modernity and industrial-like employment, which only looked at jobs and respite from jobs as happiness, were in fact antithetical to the Indian nature of living. To him, the leisure state would be an abomination of boredom. “This situation, in which each man does what is naturally (kata phusin = Skr. svabhâvatas) his to do (to heautou prattein = Skr. svadharma, svakarma), not only is the type of Justice, but furthermore, under these conditions (i.e., when the maker loves to work), “more is done, and better done, and with more ease, than in any other way.” (A Figure of Speech or a Figure of Thought)

Coomaraswamy asks the social reformer to reflect on “whether the traditional systems were not in fact designed to realise a kind of social justice that cannot be realised in any competitive industrial system where all production is primarily for profit, where the consumer is a guinea pig, and where for all but a fortunate few, occupation is not a matter of free choice, but economically, and in that sense arbitrarily, determined?”

For both Sri Aurobindo and Coomaraswamy, the varna-jati arrangement, along with the four ashramas of life (Brahmacharya or student, Grihastha or householder, Vanaprastha or forest dweller, and Sannyasa or renunciate), working in the framework of the four purusharthas of life (dharma, artha, kama, and moksha), was the brick and mortar of Indian civilization. Moksha, or liberation, was the final ideal of the culture, and dharma was the means to achieve it. The dharma of the king, as stated in most Indian treatises, including Kautilya, was to maintain the varna and jati order of society. As highlighted before, enlightened monarchies, free citizens, and decentralised political units glued together by spiritual and cultural unity were the essence of political India in the past.

Elaborating on Ananda Coomaraswamy’s ideas, Manjushree Hegde (Ananda Coomaraswamy on Caste) refutes the oft-repeated criticisms of the caste system. According to proportionate law, a king or a Brahmin has a much heavier punishment than the Sudra for the same offence. Caste discrimination was strict only in terms of rules against intermarriage and inter-dining. She quotes T.W. Rhys Davids, who says, “Evidence has been yearly accumulating on the existence of restrictions as to intermarriage, and as to the right of eating together among other tribes — Greeks, Germans, Russians, and so on. Both the spirit, and to a large degree, the actual details of modern Indian caste usages, are identical with these ancient, and no doubt universal customs.”

In a radically different understanding of the Indian caste system, she quotes another scholar, Birdwood: “We trace there the bright outlines of a self-contained, self-dependent, symmetrical, and perfectly harmonious industrial economy, deeply rooted in the popular conviction of its divine character, and protected, through every political and commercial vicissitude, by the absolute power and marvelous wisdom and tact of the brāhminical priesthood. Such an ideal order we should have held impossible of realization, but that it continues to exist and to afford us, in the yet living results of its daily operation in India, a proof of the superiority, in so many unsuspected ways, of the hierarchic civilization of antiquity over the secular, joyless, inane, and self-destructive, modern civilization of the West.”

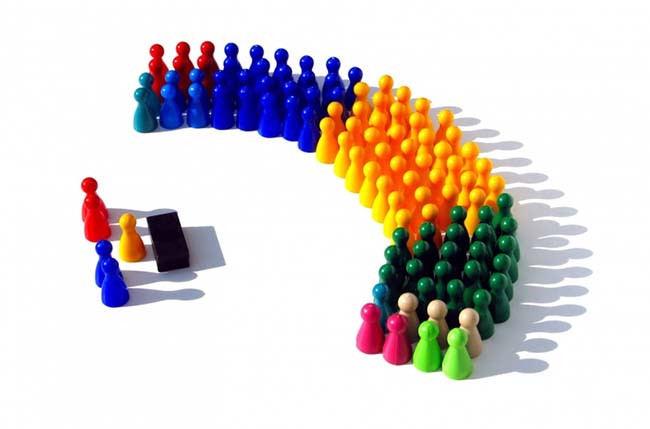

Coming to democracy, Coomaraswamy says: What we see in a democracy governed by “representatives” is not a government “for the people” but an organised conflict of interests that only results in the setting up of unstable balances of power. In his essay Individuality, Autonomy, and Function, he says that the object of any form of government (‘good’ or ‘bad) is to make the governed behave as the governors wish. A democracy that gives the right to rule through votes (it does not matter whether the margins are slender or huge) is finally a tyranny of the majority.

It allows individual autonomy for all by only two means: revolution by those who feel they have an equal right to rule, or renunciation—a repudiation of the will to govern. He says that the “will to govern” is the will to govern others, whereas the “will to power” is the will to govern oneself. Those who would be truly free have the will to power without the will to govern, and if such individuals advised the executive, this would tend to the greatest degree of freedom and justice practically possible. This was the ideal of the disinterested philosopher advising the government and taking care of the country, the highest individual who is truly free (Jivanmukta of Vedanta, Boddhisatva of Buddhism, Jina of Jainism, or the Superman of Nietzsche).

Coomaraswamy writes that there are two natures in man. Of these two, one is the mortal, or individual (outer man); the other is the immortal, or “very Person”. “When, now, we have forgotten who we are and, identifying ourselves with our “outer man”, have become lovers of our own individual selves, we imagine that our whole happiness is contained in the freedom of this “outer man” to go his own way and find pasture where he will. There, in ignorance and in desire, lie the roots of individualism. Thus, the traditional concept of liberty goes far beyond, in fact, the demand of any anarchist; it is the concept of an absolute, unfettered freedom to be as, when, and where we will. All other and contingent liberties, however desirable and right, are derivative and to be valued only in relation to this last end.”

Coomaraswamy wrote extensively on many topics still relevant to India, yet only a handful remember him, mainly as an art historian.

Liberal Democracies or Secularized Theology: The Ghent School

John Locke (1632–1704) argued for church and state separation and an opposition to authoritarianism at all levels. By consensus, his ideas laid the basis for the liberal approach of modern democracies (equal moral worth; freedom to choose one’s religion; and individual intrinsic reason), where toleration became a key moral obligation. Worldwide, the standard political philosophy is “Western liberal democracy”—a supremely reigning individual with the power to vote.

However, Balagangadhara and Jakob De Roover (John Locke, Christian Liberty, and the Predicament of Liberal Toleration) argue that the liberal model of toleration is a secularisation of the theology of Christian liberty and its division of society into a temporal political kingdom and the spiritual kingdom of Christ. Therefore, when liberal toleration travels beyond the boundaries of the Christian West or when Western societies become multicultural, it threatens to lose its intelligibility.

They say that the emergence of toleration as an unconditional moral obligation was an internal dialogue of Reformation Christianity in the sixteenth century. This religious value secularised itself and expressed itself in post-Enlightenment political theories. Previously, the mediaeval church created a spiritual hierarchy for the clergy and a temporal one for the followers. Protestantism denied this hierarchical division of humanity, saying that all believers were priests whose souls ought to be free — the core idea of ‘Christian Liberty.’

Christian liberty thus placed human beings in two realms: the kingdom of Christ (the personal spiritual sphere with God as authority) and that of human authority (the sinful body in the temporal sphere under secular laws). The two kingdoms should never mix, and state laws should never interfere in the spiritual realm. Therefore, toleration of diverse beliefs became a moral duty of all states, and spiritual liberty became the basic right of all humans.

Later, the anti-confessional Protestant denominations fought with the confessional denominations but retained the notion of Christian duty to tolerate heresy, idolatry, and other violations because universal liberty of conscience is God’s gift to humanity. Locke’s model, derived from the Protestant Reformation theologies, divides human social life into two spheres: civil interests (liberty, health, money, lands, and furniture) and religious pursuits. Legislative power restricts itself to only civil interests. The new political liberalism retains the twofold structure of a private personal sphere (which includes personal moral or religious doctrines) and a public political sphere (governed by a neutral justice).

This structure is, however, problematic in identifying the two spheres and drawing their limits. What is the limit of tolerance for pornography or public smoking? Where does liberty end, and where does state coercion begin? A central concern of liberal theorists throughout, the standard criterion today in liberal philosophy, politics, and jurisprudence is the harm principle—tolerating only those practises that do not harm others. Though clear for physical harm, the principle is highly obscure for psychological harm.

This theological division between civil and religious, this world and the other, body and soul, is necessary to make the concept of toleration intelligible. We cannot assume that human lives have such a ‘natural’ dual structure to explain the value of toleration to the non-modern, non-liberal, or non-western world, says Balagangadhara. The empirical criterion of the two spheres is impossible since any domain of human existence is subject to state laws at some point while being free from them at other points.

Compounding matters further, there is no clear definition of ‘religion’, especially in the Indian context. Today, India has intense friction over liberal toleration in two important areas: the Uniform Civil Code and conversions (a necessary dynamic of Semitic religions but unethical for Hindu traditions). ‘Principled distance’ is not an interpretation of secularism but a justification of the behaviour of the post-independent Indian state by making ad hoc modifications to liberal political theory. Liberal toleration, presupposing the truth of Christian anthropology, maximally makes sense to Jews and Muslims. Hence, Judeo-Christian theology is the condition of intelligibility for the liberal theories of toleration, and where it is not available, these become radically unintelligible.

Balagangadhara shows that one of the flaws of political liberalism is precisely the assumptions it makes about human psychology. By implicitly calling its own cultural psychology a reasonable ‘comprehensive doctrine’ and assuming its truth, one merely transforms different cultural folk psychologies into false and hence ‘unreasonable’ exemplars.’ Nineteenth-century liberalism explicitly stated that all other cultures in the world were inferior to Western culture. One present advocate says, “Political liberalism remains humanity’s best hope in a world where cultural diversity is not only a fact but a joy of living.”

The theory of political liberalism is intolerant to the point of being arbitrarily tyrannical. Following a dialogical structure where a priori Western liberalism is the best and the others are flawed brings about a skewed and unjust consequence for non-western culture. Reasonable pluralism, which assumes the inevitability of reasonable people coming to different reasonable judgements, forcibly bows to the logic of liberalism’s cognitive mechanisms and denies pluralism, affirming the familiar theme of Western superiority.

In the final part, we shall look at how modern understandings cause immense chaos in the true understanding of India. We are doing well, but we can do better only if we look afresh at our traditions, which hold solutions for the entire world, in fact. We shall also see how the story of India is in gross contradiction to much of the narrative set by the colonials and missionaries. They did what they had to do, but the saddest thing is that collectively, even after decades of independence, we could not reject many of the stories the West told about us despite their falsity and the persistent damage they are doing to us.

Concluded in part 4

SELECTED REFERENCES AND FURTHER READINGS

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249725298_John_Locke_Christian_Liberty_and_the_Predicament_of_Liberal_Toleration John Locke, Christian Liberty, and the Predicament of Liberal Toleration by Jakob De Roover and S.N. Balagangadhara (Political Theory36(4):523-549 DOI:1177/0090591708317969)

- Sri Aurobindo and India’s Rebirth by Michel Danino

- https://www.academia.edu/49076425/Sri_Aurobindos_Vision_of_Indias_Rebirth Sri Aurobindo’s Vision of India’s Rebirth by Michel Danino

- https://www.academia.edu/23950683/The_socio_political_philosophy_of_Sri_Aurobindo The socio-political philosophy of Sri Aurobindo by Dr. Debashri R Banerjee

- https://www.academia.edu/28749683/The_Spiritual_Nationalism_and_Human_Unity_approach_taken_by_Sri_Aurobindo_in_Politics The Spiritual Nationalism & Human Unity: approach taken by Sri Aurobindo in Politics by Dr. Debashri R Banerjee

- https://www.academia.edu/30089365/Aurobindos_Theory_of_Nation_State_is_it_contrary_to_the_Saptanga_Rastra_Tattva_of_Ancient_India Aurobindo’s Theory of Nation-State: is it contrary to the Saptanga Rastra Tattva of Ancient India by Dr. Debashri R Banerjee

- https://incarnateword.in/sabcl/15 The Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo Volume 15 (Social and Political Thought: The Human Cycle—The Ideal of Human Unity—War and Self-Determination)

- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy: The Bugbear of Democracy, Freedom, and Equality in The Betrayal of Tradition: Edited by Harry Oldmeadow

- A Figure of Speech or a Figure of Thought? In The Essential Ananda Coomaraswamy edited by Rama P Coomaraswamy

- Individuality, Autonomy, and Function in The Dance of Shiva by Anand Coomaraswamy

- Spiritual Authority And Temporal Power In The Indian Theory Of Government by Ananda K. Coomaraswamy

- Caste — According to Ananda Coomaraswamy by Manjushree Hegde https://pragyata.com/caste-according-to-ananda-coomaraswamy/

Leave a Reply