"The political spectrum teaches absurdly that opposites are the same. The two ‘positions’ - Left and Right - are the mixing of incoherent, unrelated, and constantly shifting ideas lumped together by the accident of history. Aggressive military positioning hardly connects to a free-market philosophy. Defenders acknowledge this variation but claim an underlying essence: the Right (conservatives), ‘backward looking’, want to conserve; the Left (progressives), ‘forward looking,' want change. Both wings' policies, in fact, are ‘backward-looking’ and marked by nostalgia, depending on the issue."

In the first installment of the series titled "Understanding Political Systems Of India", Dr. Pingali Gopal analyses the multiple prevalent political systems and ideologies of the West, that define world politics as we know it today. These systems have been allowed to influence Indian politics and policy making after independence, with complete disregard to the ancient political systems of India.

The broad classification of political ideology as Right or Left is nebulous at best - one can falsify every proposed essence of right or left, which shows us that ideologies are nothing but social constructs. these Right-Left political ideas do not make sense either in the Western context or in the Indian context, and yet, for decades, we have held on to them. We need to understand our past political systems better, and we need to transcend the paradigm.

Understanding Political Systems Of India – Part 1 – Political Ideologies – A Dummy’s Understanding of Background Western Theories

Introduction

India’s ancient and mediaeval political history was largely absent from public consciousness during colonial rule. Post-independence, India continued with English political ideas. People in power after independence, undoubtedly with a deep love for the country, were mostly products of Western education and training. Their modernization philosophy looked with disdain at traditional India. The Orientalist view of a past decadent India, partially corrected by the British, was the prevalent attitude, which is now embedded deeply into our collective psyche as colonial consciousness.

Bhikhu Parekh (The Poverty of Indian Political Theory) wonders how a rich Indian tradition, with great philosophies and intellectual freedom, could not throw up an indigenous political theory for self-rule. Indian thinkers were not completely enamoured by Western political thought. Sri Aurobindo believed that India’s future should root in its own ethos, and a blind aping of European ideals in terms of politics, administration, morals, ethics, and law would be a recipe for disaster. We had a character of our own; foreign rule destroyed our shell, but the core was still intact. He was critical of both the parliamentary system of European democracy and that of Russian socialism, or communism.

The power structures completely ignored all such thinkers.

After independence, due to a series of political machinations, a Marxist ideology gained control of the narrative of India, which distorted the situation even more. The country came out of the grips of the monotheistic influences of Islam, Christianity, and some form of Marxism when, in 2014, the BJP took hold of the country. This reactionary and ‘right-wing Hindu’ political gain may provoke hostilities even more than before.

Let us first look briefly at what politics and ideology mean at the popular level of discourse. Later, we shall see how these political theories may have a limited application to India; they may even be dangerous.

Forms of Government

The simplest definition of a government is a system governing an organised community, commonly a nation (a group of people with some commonalities) or a state (a geographical area belonging to a nation of people). The nation-state is now a unified notion. The legislature, executive, and judiciary form the three estates of the government.

In India, the legislature is the Parliament with its two houses: the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha. The legislature makes laws and elects the Prime Minister, the President, and members of the executive. The President, the Vice President, and the Council of Ministers, with the Prime Minister as its head, form the Executive Union in the traditional definition. In a broader sense, it also includes the non-political permanent civil service office. The powerful executive gives shape to and implements the legislative laws reflecting the government’s policies.

The Judiciary consists of the judicial system’s network, starting with the Supreme Court. This system interprets and applies the law in the name of the state; it is an important mechanism to maintain law and order and settle disputes of any form at any level, from the individual to the collective. The judiciary cannot make laws (legislative responsibility) or enforce laws (executive responsibility). Through judicial review, however, it can change or modify laws. The three interdependent, yet independent, estates create enough checks and balances to prevent faulty ideas and people from damaging the country.

Why do governments exist?

As one author (Anne-Marie Slaughter) elaborates, the most important is the protection of its citizens from physical, mental, and intellectual violence, either inside or outside the country. This idea of a protector requires taxes to equip an army and a police force, to build courts and jails, and to elect or appoint officials to pass and implement the laws. Next, the government is a provider of goods and services that individuals cannot provide for themselves. This ranges from infrastructure building to creating a welfare state policy for challenged citizens like those in old age, sickness, disability, and unemployment. The final role of the government is to encourage citizen capabilities by investing in areas like education and nurturing talent to meet economic, security, scientific, demographic, and environmental challenges for the country.

An ideal government ensures freedom of expression, the rule of law, equality of opportunity, and the integrity of the country. Political thinkers across centuries struggled to decide the best form of running the country by the ‘wisest and the best.’ Is it democracy (an ideal norm today), monarchy (single-person hereditary rule), oligarchy (a group of people distinguished by nobility, wealth, education, and holding equal powers), autocracy (strong central party or military power monarchical or oligarchic in nature), or totalitarianism (extreme control)? Generally, as power concentrates more in the ruling elite, the citizen’s power reduces. What is the golden balance?

Some Philosophers on Democracy

Democracy is the best form of government, according to popular, academic, and intellectual opinion. However, thinkers across centuries raised problems with democracy and believed that it was not indeed a good method of administering the country. Will Durant (The Story of Philosophy) discusses many philosophers critical of democracy.

Plato (4th century BCE) could not think of democracy as an ideal form of governance. Plato believed that every form of government tends to perish in excess of its basic principle: aristocracy by limiting too narrowly within power circles; oligarchy by the scramble for wealth. Following a revolution, democracy arrives and gives people an equal share of freedom and power. But even democracy ruins itself in excess of its basic principle of an equal right for all to hold office and determine public policy. However, Plato says people lack the education to select the best and wisest rulers. Oratory skills and the ability to garner votes become more important to winning power than ability, even as nepotism, corruption, and general incompetence become widespread in a democracy. The upshot of such a democracy is tyranny.

For Plato, the ideal was a democratic aristocracy where everybody has an equal opportunity to reach the seat of power as ‘philosopher-kings’, without the hypocrisy of voting.

Plato’s pupil Aristotle also thought government was too complex a thing to have its issues decided by numbers rather than knowledge and ability. For Aristotle, democracy has a false assumption that those who are equal in one respect (like the law) are equal in all respects, including governing. Aristotle scathingly says that in a democracy, ability sacrifices itself to number, while trickery manipulates numbers.

In Francis Bacon’s ideal world, the government is of and for the people, but by the ‘selected best’ of the people. Similarly, Spinoza also wanted to limit office to men of ‘trained skill.’ He thought that democratic governments had become a procession of brief-lived demagogues, with men of worth avoiding political office. Spinoza was clear that, despite being a reasonable option, democracy still had to solve the problem of selecting the ‘wisest and the best’ to rule themselves. Freidrich Nietzsche, a German philosopher who observed forms of government, believed that the ideal society divides into three classes: producers (farmers, proletaries, and businessmen), officials (soldiers and functionaries), and rulers. Like Plato, he believed philosophers were the highest men.

Importantly, the best intellectuals of the Western world, from Socrates down to the contemporary period, were acutely aware of the problems with democracy. Yet, over the centuries, through revolutions, public opinion, and emotions, it has become the norm — an “ought to” — all over the world. The major issue is the balance between individual rights and government rights, with the extreme ends being anarchism and totalitarianism, respectively. The golden mean is apparently democracy today.

Political Ideologies in The Modern World: Left, Right, and Centre

Political Ideologies by Andrew Heywood is a wonderful resource for giving a basic understanding of political ideologies. Though the exact definition of a political ideology is elusive, it can mean: a) a political belief system; b) an action-oriented set of ideas; c) the ideas of the ruling class; d) ideas that generate a sense of collective belonging; e) a doctrine that claims a monopoly of truth. All ‘isms’ finally try to balance individual rights and state rights. Practically, the citizen would want the freedom to pursue desires, acquire property, and seek happiness without state interference. The citizen would also want strong protection for individual pursuits from the state.

‘Left’ and ‘Right’ date to the French Revolution (late 18th century), when a legislature replaced the aristocracy. In the seating arrangement, members of the aristocracy supporting the king sat on his right, while ordinary members sat on his left. Gradually, the term “right” began to mean ‘monarchist’ or ‘reactionary’ to retain an old order, and “left” began to imply ‘revolutionary’ tendencies with egalitarian motives.

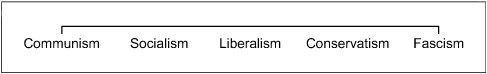

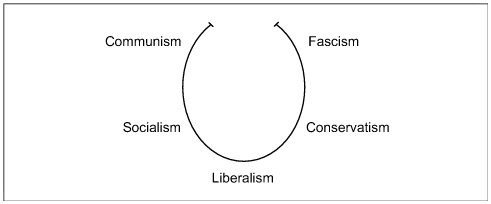

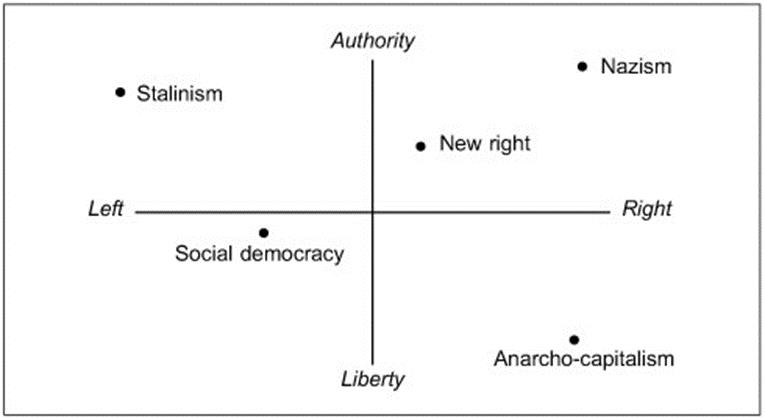

The left and right wing, in popular understanding, differ in dealing with two aspects: individual policy and economic policy. The left allegedly would want equality for all and a centrally planned economy with desirable collective ownership. The right, again allegedly, would believe equality is impossible and that the best economy is free-market capitalism. There are any number of intermediate positions. Some represent the political spectrum as horseshoe-shaped because the extremes of communism and fascism become similarly ‘totalitarian’. The pictorial representations only simplify the understanding; at a practical level, governments tend to be complex combinations. Feminism, environmentalism, and animal rights activism now make for a heady mix as they enter political discourses.

Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism: The Traditional Right, Center, and Left

Liberalism, an outcome of Western industrialization in the late 19th century, came with the Constitution and democracy. Classical liberalism implies an individual with the maximum possible freedom. The state only maintains domestic order and personal security with minimal interference in the economic policies of a self-regulating free market. Modern liberalism (social or welfare liberalism) gives the state more powers to prevent unbridled capitalism.

Conservatism, traditionally placed on the ‘right side’ of ‘central’ liberals, tries to preserve the traditional order and resist change. It attempts to respect the accumulated wisdom of past individuals, institutions, and scriptures. Change is not a revolution but a gradual, organic, traditionally rooted, and debated evolution. There are various forms of conservatism: authoritarian conservatism (strong authority from above establishing order); paternalistic conservatism (a more prudent version of strict authority); and libertarian conservatism (advocating free-market laissez-faire liberalism but with a central authority). Adopting a more welfare-state approach, conservatism could garner public support in democracies. Conservatives essentially say that experience and history guide future political action rather than abstract principles of freedom, equality, and justice. The continuous criticism against conservatism has been that attempts to preserve the status quo are for the sake of the dominant elite’s interests.

Socialism, where the collective subsumes the individual, opposes capitalism. Social interaction and membership in collective bodies make cooperation more important than competition. Each person ‘works to the best of their ability, and each gets as per the needs’ by the state. The state attempts egalitarianism — a society of equals. The industrial capitalism of Europe, giving rise to a hugely disadvantaged and poor working class, originated socialistic ideas against the exploitative principles of a free-market economy.

However, a simple core philosophy has diverse traditions. Utopian socialism argues on moral grounds for allowing more compassion between human beings. Scientific socialism is a scientific Marxian analysis of historical and social developments, predicting that ‘socialism’ would inevitably replace ‘capitalism’.

Regarding the means, revolutionary socialism propagates revolution, throwing out the existing political order. Reformist or democratic socialism believes in the parliamentary system and basic liberal democratic principles such as constitutionalism.

As to the final ends, fundamentalist socialism (Marxists and Communists) attempts to completely replace the capitalist systems with common ownership, and revisionist socialism aims to reform capitalism as a balance between the moral aspects of socialism and a more liberated economy. India after independence was an example of democratic or revisionist socialism. Socialism with deep state control invariably tends to stifle individual freedom and liberty.

Communism takes a stricter stance against capitalism, preferably through a revolution. For them, society consists of two classes: the bourgeois and the working proletariat. Marx believed that in the ultimate struggle between the two classes, the proletariat invariably wins over the hegemonic class to create a new classless society. The economy would exist without private ownership. Trying to distinguish between socialism and communism might seem a bit difficult. In the early phases, socialism aimed to socialise production only, while communism aimed to socialise both production and consumption. Traditional Marxists employed the word socialism in place of communism. Following the Bolshevik Revolution, socialism became an intermediate term between capitalism and communism.

Russia and China are traditional socialistic-communistic countries, but they have their own criticisms. The Russian Lenin and Stalin forms of communism were more state-controlled capitalism and single-party rule, leading to totalitarianism. The economic model of China appears to pay only lip service to Marxist or communist principles. Religion, family, and traditional social structures that bind individuals take a secondary role in the socialist or communist way of thinking. Traditionally, people consider communists to be atheists. In the latter part of the 20th century, communism collapsed in Eastern European countries.

Other Political Philosophies

Most political ideologies are a variable mix of the three main forms, but there are other forms of some relevance too. Nationalism, believing that the nation (group of people) is the central political principle, has many forms:

a) ‘classical’ political nationalism uses common bonds like culture, ethnicity, religion, language, and traditions;

b) liberal nationalism with a right to self-determination;

c) conservative nationalism defending traditional values and institutions; and

d) expansionist nationalism, exemplified by colonial Europe, an aggressive form of nationalism.

Expansionist nationalism, in turn, ironically brought anticolonial nationalism to Africa and Asia. Nationalism subsumes the individual for the sake of the larger, but the underlying character has ranged from extreme left to extreme right in its thinking.

Feminism, a relatively contemporary ideology, seeks to address the social role of women and their subjugation to men in most societies. It is a transnational movement seeking political, social, economic, and cultural equality with men. There are many forms of feminism: liberal, socialist, and radical feminism previously; eco-feminism, black feminism, and postmodern feminism more recently. The first wave of feminism in the mid-19th century was about universal voting rights. The second wave, a century later, was a more vociferous demand for equal rights. The third wave emerged in the mid-1990s in the developed world, seeking to modify perceptions of gender as a continuum rather than a strict binary of male and female. Gender identity and its expression became independent of biological sex. Feminism has exposed gender biases in the social, political, and domestic worlds sharply, and there have been many reforms in the Western world. However, people now talk about the collapse of feminism and a post-feministic world because of internal differences and its restricted western relevance, according to some.

Fascism, a fashionable word to use for many politically powerful people, thankfully remains within the confines of history (the period between the two world wars) and not contemporary society. The philosophy of fascism would be ‘everything for the state; nothing against the state; nothing outside the state‘. The definition of fascism has been based on what it opposes, a reason for its contemporary broad application to people and parties; it can thus be anti-rational, anti-liberal, anti-conservative, anti-capitalist, anti-bourgeois, or anti-communist.

Italian Fascism under Mussolini (1924–23) was an extreme statism based upon unquestioning loyalty towards a ‘totalitarian’ state. Hitler’s Nazi dictatorship in Germany was another manifestation of fascism, but some view fascism and Nazism as distinct ideologies. Nazism based itself on Aryan supremacy theories and virulent anti-Semitism, which led to great genocides. Neo-fascism, or ‘democratic fascism’, a contradiction of terms, stays away from totalitarianism and overt racialism but concerns itself with anti-immigration campaigns and a hyper-nationalism against globalisation.

Anarchism is an individualistic philosophy with a complete rejection of any form of government, basing itself on human goodness and love rather than any form of top-down control. It does not have a place in any country’s governance, thankfully, but some of its principles have given important insights into issues like individual liberty, ecology, transport, urban development, consumerism, new technology, and sexual relations, says Andrew Heywood (Political Ideologies).

Postmodernity and Globalisation in the Contemporary World

According to social theories, the ‘core’ political ideologies of liberalism, conservatism, and socialism arose in response to modernization. This modernization had social (dominant middle and working classes), political (constitutional democracies replacing monarchical absolutism), and cultural (commitment to reason and progress) dimensions. Post-modern societies replace class, religious, and ethnic values with intense individualism, leading to movements like feminism, gay rights movements, and environmentalism. Similarly, globalisation created a borderless world, challenging political nationalism. Globalisation also becomes the new imperialism to resist and revolt against, and hence, religious fundamentalism also arises as an opposing force.

The contemporary world has gravitated towards a liberal democracy as some sort of norm. Liberalism, at its core, demands individual freedom to practise its values without interference from the state. The state must remain neutral between all opposing camps without favouring any group. This is the liberalism that was the basis of secularism in European nations.

Bashing the Left

Roger Scruton (Fools, Frauds, and Firebrands: Thinkers of the New Left) criticises the left thinkers who understand every aspect of historical, social, economic, legal, and civic life as class struggles between the bourgeoisie (controlling the means of production) and the proletariat (in control of labour). There is silence when the realities do come up, like with Stalin or Mao. Marxist studies conclude that the production of material goods is the real motor of social change, a misleading account of modern history in which legal and political innovation have often been the cause of economic change, says Scruton.

The exploiter and exploited paradigms explain any historical, political, social, and economic turmoil; an example is the dubious Aryan-Dravidian discourse in the Indian context. Scruton says, ‘Marxist history means rewriting history with class at the top of the agenda. And it involves demonizing the upper class and romanticizing the lower.’

In different countries, the left has had different agendas: consumerism, gay rights, human rights, women’s rights, eco-rights, and so on, but the revolutions never clearly spell out the alternatives. The left thinkers, random and obscure, sometimes clothe their language in a pseudo-mathematical language. Scruton speaks of a prominent thinker, Dworkin, who argues that the right to speech exists to protect the dignity of dissenters. Thus, remarkably, a truly sincere government, after having passed a law, should be lenient towards those who disobey it!

Thomas J. DiLorenzo (The Problem with Socialism) claims that everything is wrong with socialism. Free education, healthcare, and houses as a right without the need to work are indeed attractive, but someone must pay for them. These are the taxes that only hide the cost. Every single tax payer works a third of the year in the USA to pay all the taxes owed to the state machinery. Soviet Russia, Chile, Argentina, the democratic ‘Fabian’ socialism of Britain, Argentina, the Nehru-Mahanalobis five-year plans of post-Independent India, and China before opening are all examples of socialistic administrations destroying the country’s economic fabric. Totalitarian, socialistic countries like Russia were disasters for personal freedom and liberty. A lack of incentive to work, central planning ignoring local intricate market forces at work, and bureaucratic plans replacing rational economic plans are the main reasons for the worldwide disaster of a socialistic economy.

Egalitarianism looks good in theory, but human beings are unequal in talent and merit. Islands of socialism in the form of government enterprises like schools, libraries, post offices, railways, banks, police, and so on have always been loss-making bodies across the world, says DiLorenzo. Socialists throughout history have stood on a negative programme of ‘hatred of an enemy or envy for the better off’. The enemies could be the aristocrats, Christians, capitalists in Russia, Jews in Germany and Austria, plutocrats in Europe, and ‘Wall Street’ or the wealthy ‘one percent’ in the USA. To a socialist, the ends justify the means, which is the reverse of traditional morality and can hence justify any action desired by the socialist.

Death counts, up to 100 million in the 20th century, have been the highest under socialist regimes the world over, as the ‘The Black Book of Communism’ catalogues them. DiLorenzo says that intellectuals prefer to pontificate that socialism, an ideology associated with the worst crimes, the greatest mass slaughters, and the most totalitarian regimes ever; is more compassionate and humane than free market capitalism. The latter alleviated poverty more, created more wealth, provided more opportunities for development, and supported human freedom more than any other economic system in the history of the world.

Welfare programmes in socialism have the defining moral hazard that the benefits destroy the incentive to find a job and become financially independent. In the USA, welfare programmes since the late 1960s have increased levels of poverty instead of alleviating it! Peculiarly, as the welfare state replaces the earning father and the stigma of illegitimacy shrinks away, children in a traditional two-parent family are steadily declining (above 45%), especially amongst blacks in the USA.

Wars of economic conquest are invariably the result of some variant of mercantilism, socialism, or autarky (self-sufficiency of production), three economic theories that put the interests of the state in controlling the military first. Capitalism, which encourages international free trade, is almost never the reason for war. Socialists propagated a huge myth against a free-market society. The environment has taken a bigger hit under socialism across the world in the quest to use resources without any individual liability, says DiLorenzo.

Bashing the Right

The liberals and the ‘left’ bash with equal force the ‘right’ (conservatives or the Republicans) as domination by an elite incompatible with democracy, prosperity, and civilization. According to them, conservatism promotes inequality and prejudice. Preserving institutions that have apparently stood the test of time and a gradual organic change; believing in the hierarchy of orders and classes; and defining freedom in a concocted manner by internalising domination are the hallmarks of conservatism, say the critics. Liberals feel that conservatism works by destroying conscience, rejecting democracy, and opposing rational thought. Previously, it was by denying education, and in the modern era, it is by the invention of public relations—a rationalised irrationality. Conservatives destroy reason by using the trick of “projection,” attacking someone by falsely claiming that they are attacking you.

In the modern industrialised era, kings have given way to corporations and the prosperous middle class to subjugate the common masses in the new avatar of conservatism. The conservatism of the late 20th century was especially vituperative in its campaigns against the relatively autonomous democratic cultures of the professions, says one author, Philip Agre. Thus, a new subfield of public relations, issues management, and the invention of think tanks have subverted democracy, the critics of conservatism say.

Fascism: Right or Left?

Media, the film industry, intellectuals, and academic institutions play an important role in reinforcing the discourse of associating fascism with the ‘right-wing’ agenda. World over, the so-called right and its cousins like “Conservatives” or “Republicans” are always on the defensive in trying to prove that their actions are not fascistic, as the overwhelming diatribe comes from the other side. However, fascism might in fact be a manifestation of extreme leftist socialistic ideology.

Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini, and Japanese imperialism, examples of gross fascism, were all national or international socialists. Fascism began with socialistic ideologies, complete governmental control of all institutions, and a hatred for private enterprise. The dogmas of German fascism were the abolition of private property, the sacrifice of individual freedom, the show of unity by indulging in violence against any defined enemy, the regulation of private business, and centralised governance. Education as a free commodity for indoctrination, intolerance to opposition, and being at continual war with individuals, families, private businesses, and the church to bring about a great reordering of society are common themes for both socialism and fascism.

Stalinist propaganda repeatedly claimed that the only alternative to Russian socialism was fascism, and thus the latter became the extreme right. Fascism now abusively refers to any government or individual in power trying to impose its views on non-consenting citizens. The fascists were strictly anti-Church, and the same philosophy of ranting by the socialists continues with respect to religion.

Jonah Goldberg argues that contemporary conservatism has neither roots in nor an affinity for fascism. Contemporary liberalism ironically retains an affinity for fascistic ideas through its profound indebtedness to progressivism. Group loyalty was the highest principle in Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, which were socialistic in character. Goldberg claims that liberals, leftists, progressives, and Democrats have always created moral equivalents of war to create an equal brand of fascism. In matters of economics, politics, sex, gay rights, abortions, environmental protection, citizen rights, and race inequalities, the liberals always appeal for unity and come together in the form of a ‘revolution.’

A prime example of the liberal left’s similarity to fascism is in the field of eugenics, a shameful chapter in the history of humanity in the early 20th century. Hitler was obsessed with the creation of the perfect race. Later, the prime drivers of eugenics were the liberal democratic “anti-fascist” presidents of the US, like Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt. The philosophy of science and technology as a prime mover in the scheme of things, the ends justifying the means, and attitudes against religion have a striking similarity between fascistic and liberal left-wing ideology, argues Goldberg.

In abortion too, the left-liberal support of pro-choice resonates more with the fascistic ideology of sacrificing the individual for the collective good. ‘Green fascism’ (carbon footprints, global warming, humans as a source of all problems, redemption of collective guilt by individual efforts, the individual for the whole) creates environmental scares today like the Nazis were previously obsessed with air pollution, nature reserves, and sustainable forestry. Is fascism extreme right or extreme left?

Do All These Make Sense?

As we shall see later, these right-left political ideas do not make sense either in the Western context or in the Indian context, and yet, for decades, we have held on to them. We need to understand our past political systems better, and we need to transcend the right-left paradigm. The simplistic models for political spectrums have created confusion, hostility, and dogmatism rather than illumination, writes Hyrum Lewis (The Myth of Left and Right and It’s Time to Retire the Political Spectrum). The author completely debunks the idea that there is some kind of essence in the terms ‘right’ and ‘left’. They have simply been ‘tribal’ solidarities joined by some common issue or cause. The later issues to support or oppose simply are a matter of conforming to the group solidarity. The political ideas of both the left and right have flipped in reverse directions across time in the USA and it is remarkable that without any essentialist definition, entire populations have been in the trap of a genuinely false narrative.

Adolf Hitler and libertarian Milton Friedman are on the ‘far right,’ yet Hitler advocated nationalism, socialism, militarism, authoritarianism, and anti-Semitism; Friedman advocated internationalism, capitalism, pacifism, civil liberties, and was himself a Jew. In short, the political spectrum teaches absurdly that opposites are the same. The two ‘positions’ are the mixing of incoherent, unrelated, and constantly shifting ideas lumped together by the accident of history. Aggressive military positioning hardly connects to a free-market philosophy. Defenders acknowledge this variation but claim an underlying essence: the right (conservatives), ‘backward looking’, want to conserve; the left (progressives), ‘forward looking,’ want change. Both wings’ policies, in fact, are ‘backward-looking’ and marked by nostalgia, depending on the issue.

That conservatives love the rich and love the country and liberals love the poor and hate the country would be another concocted and simplistic story. One can falsify every proposed essence of right or left, which shows us that ideologies are nothing but social constructs, argues Lewis. The test of truth is not storytelling but prediction; those clinging to the political spectrum make no predictions. The spectrum also leads to hostility. The intense attachment to one’s brand makes way for bigotry and hatred of the ‘other’. History, the guilt of the past, and the weak points of the present are the major weapons to use against the person on the other side. Fascism, totalitarianism, and absolutism can qualify for any ideology from the opposing camp.

In the next section, we shall see how these Western notions hardly fit India and shall trace the trajectory of post-independent India and its major political issues as assessed by eminent scholar Professor Dr. Bhikhu Parekh, a Padma Bhushan awardee.

Continued in part 2

SELECTED REFERENCES AND FURTHER READINGS:

- https://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/6142/1/BLR%20conf%2C%20Bhikhu%20Parekh%20article.pdf The Poverty of Indian Political Theory by Bhikhu Parekh

- https://incarnateword.in/sabcl/15 The Incarnate Word, Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo, Volume 15

- https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/02/government-responsibility-to-citizens-anne-marie-slaughter/ 3 responsibilities every government has towards its citizens by Anne-Marie Slaughter

- The Story of Philosophy by Will Durant

- Political Ideologies: An Introduction (2022) by Andrew Heywood

- The Indian Conservative: A History of Right-Wing Indian Thought by Jaithirth Rao

- Fools, Frauds and Firebrands: Thinkers of the New Left by Roger Scruton

- The Problem with Socialism by Thomas DiLorenzo

- The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression by Andrzej Paczkowski, Jean-Louis Margolin and others

- https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/agre/conservatism.html What Is Conservatism and What Is Wrong with It? By Philip E. Agre (2004)

- Liberal Fascism: The Secret History of the American Left, From Mussolini to the Politics of Change by Jonah Goldberg

- The Myth of Left and Right: How the political Spectrum Misleads and Harms America (2023) by Hyrum Lewis and Verlan Lewis

- https://quillette.com/2017/05/03/time-retire-political-spectrum/ It’s Time to Retire the Political Spectrum

Leave a Reply