If India is to rise once again, it needs to follow the path that has sustained it for millennia.

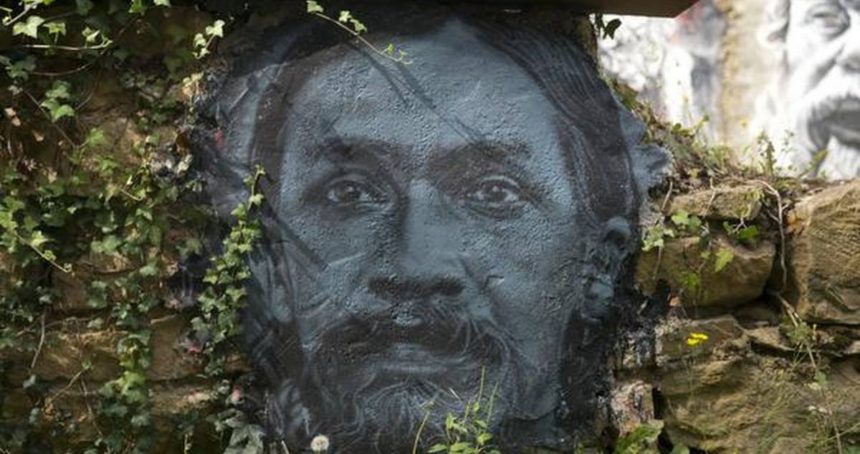

Sri Aurobindo, Spiritual Nationalism, and Indian Renaissance – II

Continued from Part 1

Dharma as Secularism

While religion can become a divisive or exclusive force in a society, dharma by its very nature is a uniting, inclusive or rather harmonising force. In the words of Badrinath, while religion and politics must necessarily be separated for a sane world, “every shade of political thought and practice that is sane must necessarily have its basis in dharma.”[x]He further explains that this confusion has caused another major misunderstanding in the contemporary Indian context – that of secularism.

“In the wake of the Enlightenment, an eighteenth-century phenomenon that was to change so radically Europe’s perceptions of itself and, therefore, its perceptions of other civilisations, the religious-secular controversy had roused such passions that if a view was secular, it had to be fiercely anti-religion.

“A secular view of life, turning into an ism as opposed to Christianity, soon became an ideology from which every human striving that was not of the material world alone was resolutely eliminated. When combined with individualism, it developed, again in opposition to Christianity, a concept of law where the main element was, not one’s ethical responsibility for the other, but legal accountability.

“That was because, by the eighteenth century, individualism had degenerated from a passionate and ennobling concern for the inviolable worth of the individual to a possessive and grasping individualism.

“This was simply not the case with Dharmic thought. Because the Indian mind did not think in terms of contesting polarities of the either/or kind, it would be yet another misunderstanding if the statement that dharma is profoundly secular is taken to mean that it is for that reason anti-religion, or that it has concern with other human beings in the form of legal accountability alone. The secular nature of dharma lies in the fact that all Indian explanations of man are evidently located in man himself, in the very structure of his being. It is that which binds one human being with another. For the ethical foundations, and the limits of one human being’s conduct towards another, were already inherent in man’s being, in the force of dharma.

Badrinath is unapologetic when he adds that over its long period of history, Indian society, like any other society, has seen plenty of instances when life fell too far off the great ideal of dharma when humanity witnessed countless examples of cruelty, violence and loss of human worth and dignity. But the point to be emphasised here is that “that was always considered adharma, disorder, a gross violation of one’s deepest being. And the corrective appeal was always to dharma.”[xi]

But what is of our concern here is this: when a word or concept such as ‘religion’ or ‘secularism,’ each of which has a unique history behind them, is thoughtlessly applied to an entirely different environment of thinking, “one history is wrongly grafted on another, which can lead only to wrong perceptions, and then to disorder in the minds of men. All social disorders originate primarily in the minds of men.”[xii]

“Just as the word dharma is untranslatable, and the word ‘religion’ conveys no substantial part of its meaning, the word ‘religion’ is similarly untranslatable into any of the Indian languages, for the concept of ‘religion’ is altogether absent from Dharmic language. As a consequence, ‘religion’ is translated invariably as dharma. This leads to a total misunderstanding and to wrong formulations. For example, derived from the notion that secularism can mean, in the field of public policy, neutrality to all religions and not necessarily anti-religion, it is translated officially in Hindi as dharmanirapekshata, which perverts, the meaning of dharma. If dharma is the foundation upon which all life is based, then nothing can be neutral or indifferent to the very thing in which it is grounded.” [xiii]

Indians today need to wake up to the true meaning of dharma as a basis for Indian national life. But before that, we must wake up to the Indian conception of life as such.

Indian National Life

The modern Indian social-political mindset, for the most part, is occupied with a secular conception of life that emphasizes a materialistic, utilitarian, mechanistic and rational view of life and universe. The modern nation-state of India since independence has also been organised around the same view of life which divides the secular and the sacred into two mutually exclusive realms.

But a deeper Indian conception of life is more integral – it is neither about a purely materialistic view of existence, nor is it about a life-denying spirituality. It is actually a meaningful synthesis of both matter and spirit. The emphasis is not only on the spirit but also on the form because it is through form only that the spirit manifests or reveals itself. Indian spirituality, at its core, is life-affirming.

It is well understood that since time immemorial, Indian quest for the Infinite has been the basis for seeking in all human pursuits such as art, literature, philosophy, music, mathematics, science, social-political organisation, etc. The ideal of dharma as the true basis for the progressive and gradual growth of the individual and society has been the organising principle for the individual and collective life. A study of ancient Indian polity suggests that dharma was indeed the real and greater sovereign than the king who was the upholder of dharma. The ideal given for the king was to ensure the proper observance of dharma by the people, and to prevent crimes, serious disorders and breaches of the peace. He himself was bound to set an example by pursuing dharma in his personal life and conduct, as well as in his regal authority and office. Anything short of that was adharma.

Dharma as an overarching, integrating and organising principle for rethinking collective life has deep implications for the kind of political, legal and governance structures and systems that the Indian nation-state may create to shape the national life and set the priorities and developmental agenda for the state machinery. By ridding itself of the artificially constructed dichotomy of secular/sacred, the social and political organisation of tomorrow’s India must be dharmic. Then alone will India be marching toward its true role and purpose.

“Dharmic civilisation had clearly seen the method of either/or as too narrow a logical framework to account for the manysidedness of life and its diversity. It saw the individual life as composed of different levels, finding different expressions at different stages of life. Reason was not opposed to faith, man was not against nature, the individual was not set against society, nor against himself. That produced in India a capacity of seeing human life with many eyes and speaking about it with many tongues.”[xiv]

In a message given to Andhra University in 1948, Sri Aurobindo wrote that India’s national destiny and her value to the world will be determined by the choice she makes. The choice is between becoming like one of the existing nations of the world “evolving an opulent industry and commerce, a powerful organization of political and social life, an immense military strength, practising power-politics with a high degree of success, guarding and extending zealously her gains and her interests, dominating even a large part of the world, but in this apparently magnificent progression forfeiting its Swadharma, losing its soul,”[xv] or whether she will be true to her heritage, “live also for God and the world as a helper and leader of the whole human race.”[xvi]

Reawakening the Shakti

“If India is to survive, she must be made young again. Rushing and billowing streams of energy must be poured into her; her soul must become, as it was in the old times, like the surges, vast, puissant, calm or turbulent at will, an ocean of action or of force.”[xvii]

Sri Aurobindo wrote these lines in Bhawani Mandir.

Today’s India is, demographically speaking, a young nation. But is that young energy on its way to becoming an “ocean of action or of force”? And more importantly, have we – our education, our popular culture, our media, our entire political and social machinery – been able to give the right direction to this young energy so that when it becomes an “ocean of action or of force” it is through creative and constructive pursuits meant to raise the individual, the society, the humanity and not be a destructive force?

“We in India fail in all things for want of Shakti.”

Sri Aurobindo wrote this too in the same work. There we find another important reminder that our knowledge too needs Shakti, otherwise it is a dead thing, he said. What will one do with knowledge of the highest ideal, the highest vision without having the shakti to execute the vision, the conscious-will, the inner force, power and strength to live the idea? India needs Shakti alone, he said forcefully.

This was written in the early 1900s, but the truth rings even more true today, in the 21st century. If we are to be reborn as a society, as a nation, if we have to raise ourselves to work toward the true mission of India, to fulfil India’s true destiny, we must grow in Shakti.

What can help Indians, and especially the youth of India grow in Shakti? What are some of the factors holding us back? What is necessary to infuse our knowledge with courage? What needs to be done to strengthen our society from within?

These are some questions that must be reflected upon in all honesty and sincerity, without the façade of political correctness or ideological prejudice. A clear look at these is important, especially for the times we live in, the times when, according to some voices, a new India is being reborn.

In many of Sri Aurobindo’s speeches delivered during the years of his leadership of the Indian independence movement, we find great clarity on his vision of a nation.

“A nation is a living entity, full of consciousness; it is not something made up or fabricated. A living nation is always growing; it must grow, it must attain its loftier heights. This may happen after a thousand years or in the next twenty years, but happen it must.”[xviii]

Let us meditate on all the depth and truth expressed in just a few words here. What does the idea of a nation as a living entity mean to us? It is not merely an intellectual idea; it is not only an emotional sentiment. But it is a throbbing living force, it is life itself. And Life must grow, must evolve, must live fully to realize its potential. That’s what a nation is. A living, growing, evolving entity, one seeking to realize its inner being, its nation-soul.

These words motivate one to sincere action and flare up one’s aspiration for a better future of this living, conscious entity called nation. These words stir the deepest and purest feelings of love for the nation, for the people, but steer away from a jingoistic, egoistic fervour that is at the base of virulent ill-will and hatred towards other nations.

Let us hear Sri Aurobindo’s reminder about the key work ahead for a free and strong India:

“To give up one’s small individual self and find the larger self in others, in the nation, in humanity, in God, that is the law of Vedanta. That is India’s message. Only she must not be content with sending it, she must rise up and live it before all the world so that it may be proved a possible law of conduct both for men and nations.”[xix]

Are we willing to rise up and live this message of India?

References / Footnotes

[x] Badrinath, p. 43

[xi] Badrinath, p. 41

[xii] Badrinath, p. 41

[xiii] Badrinath, pp. 41-42

[xiv] Badrinath, p. 26

[xv] CWSA, Vol. 36, pp. 503-504

[xvi] CWSA, Vol. 36, p. 475

[xvii] CWSA, Vol. 6, p. 83

[xviii] CWSA, Vol. 6, p. 812

[xix] CWSA, Vol. 8, p. 55

Leave a Reply