As an independent nation-state, India still needs to heed Sri Aurobindo's advice to truly be free.

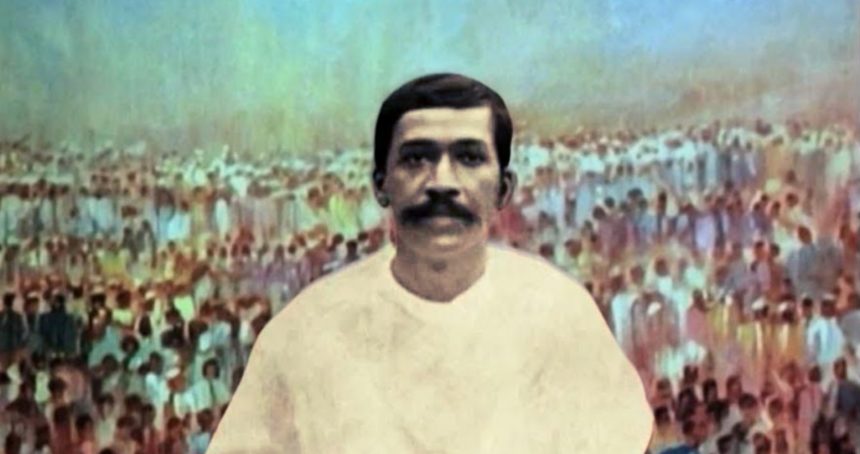

Sri Aurobindo, Spiritual Nationalism, and Indian Renaissance – I

“The future belongs to the young. It is a young and new world which is now under process of development and it is the young who must create it. But it is also a world of truth, courage, justice, lofty aspiration and straightforward fulfilment which we seek to create. For the coward, for the self-seeker, for the talker who goes forward at the beginning and afterwards leaves his fellows in the lurch there is no place in the future of this movement. A brave, frank, clean-hearted, courageous and aspiring youth is the only foundation on which the future nation can be built…”[i]

India today is politically free. But is free India on her way to rediscover her unique temperament, her true role and mission? Are we as a people working toward a true Indian renaissance that is grounded in India’s eternal spirit and truths? India is a civilisational nation and to see and know India only from the vantage point of a modern nation-state is to see and know only the outer surface. Today, as India goes through a deeply significant transition in the process of her rediscovery of her own way, a deeper way of being, it is critical that Indians must know India from a deeper vantage point.

India’s renaissance is significant not only for her future but the future of the world because it is India alone which can show humanity a path to a newer, a greater, a deeper and a higher way of being – being in harmony with nature and with one another, with the world around and with the world within.

Before India can lead the world, her children must be first re-awakened to the true spirit and sense of her being, her true nature. We, Indians, must rise up to fully grasp and realise the truth about what India is in her soul. Only then will we be able to grasp what forms would a true Indian renaissance take.

August 15, Sri Aurobindo’s birthday and India’s Independence Day, is a good day to remind ourselves of the continuing relevance of Sri Aurobindo’s view of spiritual nationalism for today’s and tomorrow’s India.

Sri Aurobindo’s political and revolutionary work inspired by his spiritual vision of the truth of India as the Mother, and his yogic insight into the mission and destiny of India as a spiritual leader for humanity and the world. At the outset, it must be said that mere politics was never the end-goal of Sri Aurobindo’s revolutionary work. In fact, his political writings in Bande Mataram clearly anticipate the philosophy we have come to associate with the yogi of Pondicherry. He wrote on July 3, 1907: “…the next great stage of human progress…is not a material but a spiritual, moral and psychical advance…”[ii]. He was, it may be said, intuitively aware of his work in that next stage of human perfectibility and progress.

India’s freedom was seen by Sri Aurobindo in this larger context of the destiny of humanity. He saw India as the living embodiment of the highest spiritual knowledge, and the repository of the sublimest spiritual achievements of the human race. As he wrote in the same editorial for Bande Mataram:

“India must have Swaraj in order to live for the world, not as a slave for the material and political benefit of a single purse-proud and selfish nation, but a free people for the spiritual and intellectual benefit of the human race.”[iii]

For Sri Aurobindo, India is the spiritual battlefield of the world where the final victory over the forces of the Ignorance and darkness would be achieved. He wrote about this destined mission of India in many of his writings during those revolutionary days, and also expressed that in his speeches. It was his deep inner knowledge of the truth of India’s soul and her purpose in the larger evolutionary march of humanity that guided all his work for India’s political freedom, including the ideals he put forward for his fellow revolutionaries. This knowledge was no ordinary knowledge, it was the knowledge, rather a truth-seeing, drishti of a yogi, a rishi.

For Sri Aurobindo, all political activity was God-directed. Revolution, for this yogi, was also yoga requiring great sacrifice and surrender. In his political writings, we clearly see the wide and all-embracing spirit of Sri Aurobindo’s nationalism, the spiritual nationalism of a yogi-revolutionary.

“Our ideal of Swaraj involves no hatred of any other nation nor of the administration which is now established by law in this country…Our ideal of patriotism proceeds on the basis of love and brotherhood and it looks beyond the unity of the nation and envisages the ultimate unity of mankind. But it is a unity of brothers, equals and freemen that we seek, not the unity of master and serf, of devourer and devoured.”[iv]

Indian View of Nation

Through the pages of Bande Mataram Sri Aurobindo also reminds Indians of the Indian vision of nation and nationalism. In the following long excerpt, we see Sri Aurobindo describing the truth of a nation most eloquently:

“What is a nation? We have studied in the schools of the West and learned to ape the thoughts and language of the West forgetting our own deeper ideas and truer speech, and to the West the nation is the country, so much land containing so many millions of men who speak one speech and live one political life owing allegiance to a single governing power of its own choosing. When the European wishes to feel a living emotion for his country, he personifies the land he lives in, tries to feel that a heart beats in the brute earth and worships a vague abstraction of his own intellect.

“The Indian idea of nationality ought to be truer and deeper. The philosophy of our forefathers looked through the gross body of things and discovered a subtle body within, looked through that and found yet another more deeply hidden, and within the third body discovered the Source of life and form, seated for ever, unchanging and imperishable. What is true of the individual object, is true also of the general and universal. What is true of the man, is true also of the nation.

“The country, the land is only the outward body of the nation, its annamaya kosh, or gross physical body; the mass of people, the life of millions who occupy and vivify the body of the nation with their presence, is the pranamaya kosh, the life-body of the nation. These two are the gross body, the physical manifestation of the Mother. Within the gross body is a subtler body, the thoughts, the literature, the philosophy, the mental and emotional activities, the sum of hopes, pleasures, aspirations, fulfilments, the civilisation and culture, which make up the sukshma sharir of the nation. This is as much a part of the Mother’s life as the outward existence which is visible to the physical eyes.

“This subtle life of the nation again springs from a deeper existence in the causal body of the nation, the peculiar temperament which it has developed out of its ages of experience and which makes it distinct from others. These three are the bodies of the Mother, but within them all is the Source of her life, immortal and unchanging, of which every nation is merely one manifestation, the universal Narayan, One in the Many of whom we are all the children.

“When, therefore, we speak of a nation, we mean the separate life of the millions who people the country, but we mean also a separate culture and civilisation, a peculiar national temperament which has become too deeply rooted to be altered and in all these we discover a manifestation of God in national life which is living, sacred and adorable. It is this which we speak of as the Mother. The millions are born and die; we who are here today, will not be here tomorrow, but the Mother has been living for thousands of years and will live for yet more thousands when we have passed away.”[v]

This educational enterprise was important not only during the Indian freedom movement but perhaps has become even more relevant now as present generations try to understand the value of nation and nationalism in the global age of today.

In Sri Aurobindo’s vision, the modern and free Indian nation was not meant to be a colonial copy with an outer machinery of elaborate bureaucratic structures left over by the British and now-merely-to-be-filled by the Indians – though he recognised the necessity for an effective external organisation. He envisioned the rebirth of a nation which will be grounded in India’s unique temperament shaped by her spiritual genius and conscious of her true mission. This will be a nation of people united in spirit and richly diverse in forms, eternal yet newly evolving, indigenous yet inclusive and integrative of all that continues to come from the world outside.

Nationalism for Sri Aurobindo had a spiritual aim: to recover Indian thought, Indian character, Indian perceptions, Indian energy, Indian greatness, and to solve the problems that perplex the world in an Indian spirit and from the Indian standpoint. He cautioned that an exclusive preoccupation with politics and economics – which is what we see today, almost to the abandonment of any other pursuit of life – could dwarf a nation’s true and integral growth and prevent the flowering of originality and energy. Duly recognising the significance of the outer socio-political and economic development of a nation, Sri Aurobindo reminds us to “return to the fountainheads of our ancient religion, philosophy, art and literature and pour the revivifying influences of our immemorial Aryan spirit and ideals into our political and economic development.”[vi]

In his Uttarpara speech after acquittal from Alipore jail, Sri Aurobindo reminded his fellow countrymen of the work that India must do for humanity.

“When…it is said that India shall rise, it is the Sanatana Dharma that shall rise. When it is said that India shall be great, it is the Sanatana Dharma that shall be great. When it is said that India shall expand and extend herself, it is the Sanatana Dharma that shall expand and extend itself over the world. It is for the dharma and by the dharma that India exists.”[vii]

He also clearly explained what is meant by the Sanatana Dharma, the eternal dharma. He emphasised that only that religion which embraces all others, which embraces in its compass all the possible means by which one can approach the Divine, can be truly universal, truly eternal. A narrow, exclusive or a sectarian religion can only live for a limited time and a limited purpose.

Get monthly updates

from Pragyata

Are you following us

on Twitter yet?

You can follow us

on Facebook too

Dharma, not Same as Religion

In order to truly appreciate what is meant by Sri Aurobindo’s view of spiritual nationalism – as invoked during his revolutionary work, its relevance for today’s and tomorrow’s India, and its difference from a narrow and exclusive religious nationalism, it is important to reflect on the fundamental difference between dharma and religion.

Dharma is a uniquely Indian idea which can’t be merely translated as duty, religion, code of conduct, ethical rule, moral law, or other such English language words. It is none of these and yet may have something of these. It transcends all these limiting and limited terms and yet includes some things from each of these. It is individual and universal at the same time. It is fixed and evolving at the same time, it is eternal and yet gradually progressive. It is of a person, and cosmic at the same time. It is an inner guide, which must be discovered individually, and yet must be a part of the larger dharma of the group, the nation, humanity to which one belongs.

Dharma is often mistranslated as religion. The notion of ‘religion’ as the Western intellectual tradition understood the term has been falsely confounded with the much wider, liberal and expansive Indian term ‘dharma’, leading to much of the socio-political-cultural conflicts. Chaturvedi Badrinath, in his collection of essays titled ‘Dharma, India and the World Order: Twenty-One Essays’ writes:

“There has been no misunderstanding more serious in nature than the supposition that Indian culture was fundamentally ‘religious’, in the sense in which the words ‘religion’ and ‘religious’ have been used in the West for centuries.

“These imply a belief in God as the creator of the universe, a central revelation of God, a messenger of that revelation, a central book containing the life and the sayings of that messenger of God, a central code of commandments, a corpus of ecclesiastical laws to regulate opinions and behaviour in the light of these, and a hierarchy of priesthood to supervise that regulation and control. These are the common, though in their specific contents very different, elements of what are described as the historical religions of the world.

“Dharma, the universal foundation upon which all life is based, is immeasurably more than ‘religion’; mistakenly one has been taken to be the other. It is to this confusion that we can trace most of the Western misconceptions of Indian culture. Since a great many of our political and legal institutions continue to be founded upon those misconceptions; hence most of the social and political problems that the people of India face today.”[viii]

Dharma essentially is the foundation of life, only next to the spirit, according to Sri Aurobindo. If the Infinite or seeking for the Infinite is the major chord of the Indian culture, the idea of the Dharma, according to him, is only second to it.

Based on their deep insight into the infinitely diverse and complex human nature that comes into play as human beings pursue the different goals of life through different stages or phases of life, the ancient Indian seers came up with the ideal of dharma which would sustain and hold together all this diversity and complexity. The concept of dharma covered basically all natures, all aspects of life, all situations and stages of life, and even allowed for maximum freedom, continuity and the greatest possibility of contextualization, adaptation and adjustment. Sri Aurobindo in his Essays on the Gita defined Dharma as follows:

“Dharma in the Indian conception is not merely the good, the right, morality and justice, ethics; it is the whole government of all the relations of man with other beings, with Nature, with God, considered from the point of view of a divine principle working itself out in forms and laws of action, forms of the inner and the outer life, orderings of relations of every kind in the world. Dharma is both that which we hold to and that which holds together our inner and outer activities. In its primary sense it means a fundamental law of our nature which secretly conditions all our activities, and in this sense each being, type, species, individual, group has its own dharma. Secondly, there is the divine nature which has to develop and manifest in us, and in this sense dharma is the law of the inner workings by which that grows in our being. Thirdly, there is the law by which we govern our outgoing thought and action and our relations with each other so as to help best both our own growth and that of the human race towards the divine ideal.” [ix]

Continued in Part 2

References / Footnotes

[i] Collected Works of Sri Aurobindo, Vol. 8, pp.168-169

[ii] CWSA, Vol. 6, p. 572

[iii] CWSA, Vol. 6, p. 573

[iv] CWSA, Vol. 8, pp. 152-153

[v] CWSA, Vol. 7, pp. 1115-1116

[vi] CWSA, Vol 8, p. 245

[vii] CWSA, Vol. 8, p. 10

[viii] Bardinath, C. (1993), Dharma, India and the World-Order: Twenty-one Essays. Deutschland & Scotland: Pahl-Rugenstein and Saint Andrew Press, p. 39

[ix] CWSA, Volume 19, pp. 171-173

Leave a Reply