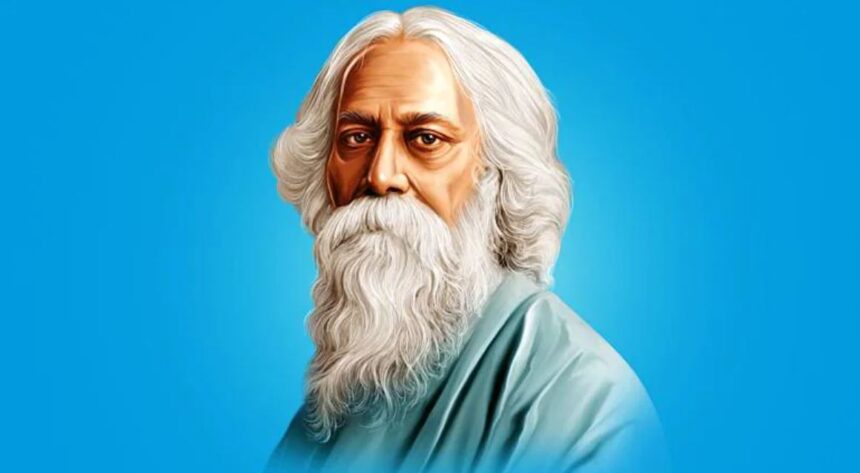

These verses are selected and translated from the poet Rabindranath Tagore’s vast repertoire of Bengali Brahamsangeet song lyrics. These song lyrics are rich in terms of literary finesse, outstanding as musical compositions of a classical or semi-classical nature; and, they demonstrate an intense religious longing in the poet – a yearning to attain and dwell in a constant state of union with the Divine.

Hymns to Brahman – Part 1; By Rabindranath Tagore

Translated from the original Bangla by Sreejit Datta

Many gifted poets and songwriters from the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century, Tagore included, have enriched the genre of Brahmasangeet (literally, ‘hymns to Brahman’) with their works. Several of these songwriters were intensely pious and meditative sort of people. Ranking among them are – apart from Rabindranath himself – Maharshi Debendranath Tagore, Bijoy Krishna Goswami, Rajanikanta Sen, Raja Rammohun Roy, and Dwijendranath Tagore (eldest brother of Rabindranath). In addition to original lyrical compositions, many of India’s most exalted sacred hymns and verses have made their way into the large pool of Brahmasangeet songs. Duly represented in this corpus of songs are quite a few Vedic mantras and Upanishadic passages, which were put into fresh but characteristically sombre tunes by Rabindranath and others. Some songs and verses composed by Kabir and Guru Nanak Dev have also made their way into the large body of Brahmasangeet songs, sometimes through adaptations, and at other times via translation. Thus, in keeping with the tradition of Vedic compilations of sacred hymns from our ancient period, and of the Guru Granth Sahib’s collections of saintly words uttered by venerable sages of the Bhakti period, the corpus of Brahmsangeet songs is really a collation of divinely inspired utterances made in India’s Modern period.

The Brahmasangeet composers have given free expression to their own religious disposition, their spiritual realisation, and their yogi-like spirit in these compositions. Their hymns and song lyrics have, consequently, coloured this genre with a palpable tone of sincere, solemn piety. Brahmasangeet songs evoke a range of emotions compatible with meditation and religious life: devotion, surrender, wonder, yearning, pathos, and ecstasy, among others. According to the feeling or mood evoked in a song by virtue of its lyrical or thematic content, an appropriate raga, or a combination of multiple raga-s, or sometimes a particular style of singing is attached to most songs in the genre of Brahmasangeet. The genre has thus become a veritable microcosm of Hindustani (and even Carnatic) music, for it contains songs in various styles of singing, in scores of raga-s, in a variety of tala-s and in multiple languages – such as Sanskrit, Hindi, and Urdu, apart from Bengali, the language in which the bulk of these song lyrics are written. The genre also represents an eclectic mix of musical styles, including dhrupad, khayāl, bhajan, ṭappā, kṛti, and Bengali-style kīrtan. Through most of these songs, the Nirākāra Saguṇa Īśvara, or the formless qualified aspect of the Divinity, is ecstatically praised, brilliantly represented, and sincerely worshipped. However, some songs, especially those written by Tagore, frequently bring up anthropomorphic features – like hands, feet, and eyes – through the imageries employed in them while extolling the Divine, Its infinite qualities, and Its benedictory actions.

As a genre of religious music and literature, Brahmsangeet offers the worshipper of Nirākāra Saguṇa Īśvara a much-needed set of symbols, which helps him or her verbalize and perform, vocally as well as aurally, some of the deeper sensations and emotions that may perhaps be collectively termed as ‘devotional surrender’ or, alternatively, ‘devotional ecstasy’. Indeed, the genre seems to maintain devotion as the predominant theme of its songs. In so doing, the genre naturally draws upon some of the already existing, time-tested musical and lyrical forms for producing the same effect – which is why we see a prevalence of the dhrupad and the kirtan styles of singing in the performance of Brahmasangeet.

Although a regular feature of Brahmo worship, Brahmasangeet, as a dynamic genre of the new Bengali religious music of the nineteenth century, has historically been performed outside the Brahmo sectarian context as well. Appearing on the Bengali cultural scene through the works of Raja Rammohun Roy only in the early decades of the nineteenth century, this form of Bengali religious songs had become a favourite of the educated and spiritually-inclined Bengali audience even before the arrival of the penultimate decade of that century. This steady rise of Brahmasangeet can be attributed to mainly two qualities: one, the solemn but melodious classical dhrupad and semi-classical kirtan singing styles imbibed in it (these two styles being a favourite of the Bengali connoisseur of music from an earlier period), and two, the fine lyrical compositions prolifically produced by a bunch of gifted Bengali songwriters. As a result, the Bengali audience, armed with its newly acquired (but at the time still evolving) renaissance sensibilities and a conscientious, refined cultural cosmopolitanism – accepted the new musical-lyrical genre with open arms. This new phenomenon in the then exciting atmosphere of fervent literary and musical activities of Bengal, became most clearly visible among those residing in cities like Calcutta, Dhaka, and Krishnanagar – the main seats of the renascent nationalist culture. In no time, songs from the then burgeoning literature of the Brahmasangeet corpus spilled forth outside the explicitly Brahmo circles; and they began appearing in the religious and ritualistic exchanges within non-Brahmo contexts – gradually becoming an integral component of the larger universe of Bengali culture. Thakur Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa Deva was particularly fond of a number of songs belonging to this genre; and none other than Swami Vivekananda (as Narendranath Datta, in his pre-monastic days) had performed such Brahmasangeet songs to his guru’s delight, on multiple occasions, as the hagiographical narratives and contemporary accounts on Thakur Sri Ramakrishna’s life inform us. In the year 1887, Narendranath had also included a number of Brahmasangeet compositions in his song anthology entitled Sangit-Kalpataru, edited and compiled together with Vaishnav Charan Basak. Evidently, the genre was a favourite of the Swami, and during his formative years, it might well have left a deep imprint on the religious, literary, and philosophical outlook of the “Patriot Prophet” of New India.

Performing music has been a part of ritual modalities as a rather ancient practice in the Indian context. It is particularly central to the Vaishnavite Bhāgavata sects, where ‘bhajan’ (i.e., praising and pleasing the Divine through singing) is part and parcel of worship. For the sake of its own theology and performative rituals, the Brahmo sect has drawn on this specific Vaishnavite influence that was predominant in Bengal since the Age of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (apart from some other sources like the Tantric tradition), and has thus adopted singing as a mode of worship right from its initial days. The translated song lyrics in this ongoing series will throw some light on the theology and religious philosophy of the Brahmo sect; and, at the same time, these will acquaint our readers with a great modern creative expression coming from within the larger Hindu cultural universe.

Dako Morey Aaji É Nishithe

Send me Your summons, yea, on this very night,

When the whole wide world is under sleep’s spell;

Come into my heart, and in silence call –

Call me unto Your bliss that is immortal!

Light up Your flame in the dark of my heart;

Send forth Your summons, yet again, and again,

To this my mind lying unconscious, soporous!

Hey Nikhila-Bhara-Dharana Visva-Vidhata

Ordainer of the World!

O Thou Bearer of All Burden!

Dispenser of Strength, the Driver

Of the Chariot of Time!

The Sun and the Moon,

As also the great stars –

All of them heavenly orbs near and far –

Are telling the rosary of Thy Name;

And so does, thru day and night,

The Eternal Spacetime!

Natho Hey Premo-Pathe

Lord,

Break all barriers down

On Love’s Way.

Let nothing come between us;

Keep me not away!

In solitude, in the crowd,

Within, as well as without,

Let me see Thee

Every day.

Kothay Tumi Ami Kothay

Where are you, and where am I?

I know not which way and how

This life is passing by

Day after night, and night after day

How much longer will thus fritter away –

O Lord of luckless ones, at your feet,

Will you take me, and let me stay?

Leave a Reply