Quite often we see people, from a tremendously large array of the political and intellectual spectrum – from left to right wings, clever to dumb beings, all in their respective capacities, built out of ahistorical whims – issuing stern statements and godly judgements about Raja Man Singh of Amer (Jaipur). He is largely seen as a “traitor, a servant of Mughals and a daughter giver.” An assumption that is less analytical and more of a crude reductionist attempt at dismissal. His image has been tarnished to such an extent that, to be on a humorous ground[1], if we let the most absent-minded of men be plunged in his deepest reveries — give that man a pencil and a paper, set his hands agoing on Raja Man, he will infallibly turn him into a traitor.

Man Singh was born into the Kachhawaha Rajput family of the Suryavamshi Kshatriyas. The earliest king known to historians of this illustrious line is Dhola, whose great-grandson founded the Gwalior fort and Sodi-dev, who came thirty-one generations after Dhola, migrated to the present place in Rajputana. And generations later came Raja Pajvan, the most celebrated of the family before the Mughal age, who fought as the dearest friend and bravest man in the army of the great Prithviraj Chauhan at the battle of Tarain. Another well-known figure in the same line was Raja Prithviraj who, with his Kachhawahas, fought alongside Mewar’s Rana Sanga at the battle of Khanua.[2]

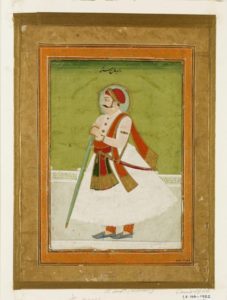

[Portrait of Raja Man Singh – Victoria & Albert Museum Collection, United Kingdom]

Later Raja Bharmal of the same line faced a desperately dangerous challenge – Muhammad Sharifuddin Hussain, the Mughal governor of Mewat, who was very keen on extending his territory at the cost of Amer. Sharifuddin threatened the frontier of Amer’s territory. Witnessing the arrant chaos and utter terror in the common man’s life and seeing the future of the whole kingdom at stake, Raja took to the alliance with Mughal emperor Akbar in 1562. Akbar ordered Sharifuddin to return war booty, hostages and leave the kingdom of Amer. Raja Bharmal’s eldest son and grandson, Bhagwant Das and Man Singh, were given high offices in imperial nobility.[3] In the following years, the enslavement of war captives was forbidden, Hindu pilgrimage tax remitted and Jiziya abolished courtesy of the Kachhawaha influence. Which can be seen as some victory in the larger tyrannical rule of Islam.

Bhagwant Das became the king of Amer in February 1573 and Kuar Man Singh being the heir apparent. Before this in 1568, Akbar had already won Mewar’s Chittor – which witnessed the barbaric slaughter of 30,000 commoners at the Mughal emperor’s orders. But despite the win, Akbar couldn’t get his hands over the whole of Mewar. Aided by the mighty Aravalli hills, which acted as a safe refuge for Mewar’s head Maharana Udai Singh till his death in February 1572 and later for his son Maharana Pratap.

Unlike the Amer kingdom – which was mere days march away from Agra and Delhi – Mewar had a strategic upper hand, the Aravalli range, with an average elevation of over 600 meters above mean sea level, and summits exceeding 1000 meters, provided a place for the forts of Kumbhalgarh (1206 meters) and Gogunda (1090 meters), both already favoured retreats of Udai Singh. Both the forts lay in the hills’ protective encirclement and their natural features, which included rocks, hillocks and dense forest, were deliberately exploited to make the forts almost impregnable.

Akbar was adamant about winning Mewar and so in his bid to sway Maharana Pratap, he asked Man Singh to reach Mewar. The meeting which followed is one of the many contentious points in the schemes before the battle. A popular, cinematic but largely mythical narrative is that Maharana considered “Mughal siding” Man Singh as an outcast and refused to dine with him. Prominent historians, including Sir Jadunath Sarkar[4], Dr Raghubir Singh[5] and Dr Gopinath Sharma[6] have dismissed the event’s fancies.

This story has no tinge of truth about it. The simple fact of an interview and Rana’s objection of going to the court has been coloured by bardic imagination” Dr Sharma writes.

Maharana Pratap, nonetheless couldn’t be swayed and the battle followed on 18th of June, 1576 between his and Akbar’s imperial forces led by Kuar Man Singh. Details of the battle deserve a river of words of its own but keeping in mind the scraggy nature of the essay, I shall give a mowed and tapered view of it.

Maharana’s forces fell upon the centre and the right of the four times larger enemy. Strength, valour and agility ensured a bloody battle. In the spur of the moment, the Mughal left side, being incessantly oppressed, fell into disorder and the field was strewn with carcasses. The valour of Maharana’s van, centre and right, was so effective that both the centre and left side of Mughals including Ghazi Khan and Asaf Khan fled away.

With the turn of Man Singh and tussle of the mighty elephants, the tables were turned. Mewari forces, being numerically disadvantaged, was pushed on to the back foot. Field turned hopeless but the immeasurable courage of Maharana kept fueling the struggle. Maharana’s nobles persuaded him to leave the field to be able to fight for another day. Maharana left, helped by Jhala Mana’s chivalrous brilliance, Shakti Singh’s sudden change and Man Singh’s careful act.

Imperial forces had the chance to pursue Maharana and his soldiers too, but Man Singh didn’t allow it. To borrow the words of RN Prasad “Kuar forbade the Mughal army to pursue Rana’s soldiers which might embarrass them.” Man Singh’s tussle with Maharana was about military superiority but still, the Kachhawaha prince knew the significance of Mewar’s chief. Man Singh won the day. But Maharana didn’t lose his spirit and despite monumental odds, he came back and won back large parts of his kingdom later in series of battles like Battle of Dewair – where 32,000 strong Mughal force surrendered to Maharana and where Maharana achieved an incredible feat in the world of brave men by chopping Bahlol Khan along with his horse into two pieces[7] – and other victorious battles like Gogunda, Chawand, Madariya, Kumbhalgarh, Mohi, Idar and Mandal. Maharana lost the battle but won the war.

Man Singh, on the other hand, after winning the day at Haldighati, prevented any plundering or destruction in Maharana’s territory as Tabaqat-i-Akbari noted. He also forbade the soldiers to loot Maharana’s territories, despite his own army starving from food, about which we know from Haqiqatha-i-Hindustan. Man Singh prevented the repeat of 1568’s Chittor. Akbarnama mentions Akbar’s suspicion and anger at Man Singh & his Rajputs’ conduct. Man Singh was recalled and Shahbaz Khan was sent to command in his place. Not only this, Man Singh’s admission to the imperial court was withheld and the imperial honours and mansabs, not only of Man Singh but also of his father, was forfeited.

Man Singh did not abandon his diplomatic approach rather doubled down on it. He saved around 7,000 temples throughout India from present Pakistan to Bengal and built/rebuilt numerous dharmik places at a pace not seen in history. He built a seven-story Govind dev temple at Vrindavan costing 1 crore at that time. He built the Jagat Shiromani temple at Amer for the Mewari queen and Sant Meerabai. He built around ‘1000 temples in Benaras’ and made it a city of temples again which were left in dilapidated condition after the destruction caused by earlier Muslim rule. Among the many temples he built some prominent ones are – Kashi Vishwanath Temple; Ramkot temple, Islamabad; Shiladevi of Amer; Laxminarayan temple and Shiv temple of Baikunth, Bihar.

[Ganesh Temple at Rohtas Fort, Bihar built by Raja Man Singh. Art by Thomas Daniell (1790)]

Man Singh was undoubtedly a very dharmic person. He never used to eat before he had finished his puja and always carried his family murti along with him wherever he went. It was Man Singh who patronized perhaps the greatest and noblest of saints in medieval history – author of the holy Ramcharitmanas – Tulsidas. Every person reading Ramcharitmanas owes it to Raja Man Singh apart from the godly saint Tulsidas ji.

His military brilliance was unparalleled and still remains to this day. Man Singh brought the famously destructive five Afghan tribes to their knees and justly ruled over the Afghan lands[8]. All other forces of the Mughal empire – including the likes of Mohammad Yusuf Khan, Raja Birbal, Zain Khan and Ismail Quli – who went to subdue the Afghans utterly failed and suffered heavy casualties, but Man Singh succeeded. Two of such instances are found in incidents of 1581 and 1586.

[Raja Man Singh’s “Pachranga” Flag which symbolises his victory over five Afghan tribes.]

In August 1581, Afghan prince Mirza Mohammad Hakim’s forces attacked the imperial army. At first, the Afghans seemed to get the better of the Mughal vanguard until Man Singh rushed forward. The Rajputs, their rank bearing elephants ahead and swivel guns mounted on their back made such as assault that “the Kabulis broke and fled away with their prince.”[9]

Afghans again rose in arms after the death of their prince in July 1585. The Yushufzai tribe attacked imperial forces in Swat fields (February 1586) which resulted in 8,000 of the imperial army dying, including Raja Birbal. Up in the mountains, Man Singh’s Kachhawahas ensured “a glorious victory” over Raushaniya sect. After which, Man Singh went to Yusufzai country and silenced them in March 1586. Man Singh later suffered illness and fever because of which, sensing weakness, major Afghan tribes rose in revolt, only to be subdued again by the Kachhawahas. Man Singh crushed Afridis in their own backyard.

Man Singh later returned to India and went to Bihar in 1588. A year later his father Raja Bhagwant Das passed away (13th November 1589). Man Singh now became the Raja. Bihar and Bengal were won by Akbar’s forces in 1574 but these victories didn’t materialize into consolidation. The numerous branches of the reigning Afghan or the noble families, maintained a semi-independent status in different parts of Bengal and Orissa, now nominally included in the Empire[10]. They were always on the lookout for any chance of rising and shaking off their alien supplanters. Such an opportunity was soon presented by the discontent of Akbar’s Muslim officers due to his “haram” anti-Islam practices and tilt towards Hinduism. All Muslim nobles in North West and East rebelled against Akbar. Afghans in Afghanistan were brought down to their knees by the Rajputs and so too in the East.

Man Singh’s rule in the East was, in the words of Sir Jadunath Sarkar,

the beginning of the longest and most glorious chapter in his life and of the records of Kachhwa achievements. He was now supreme in command and controlled both civil and military affairs; he conquered provinces and made treaties with hitherto independent sovereigns, on behalf of a distant master (the Emperor) and he lorded it over the eastern marches of India for twenty years without a break (1588-1607).”

The Afghan rule in Bihar, Bengal and Orissa was one of the darkest moments of Hindu history. Man Singh defeated and subdued the Afghans, freed the people and temples out of Muslim tyrannical clutches and built hundreds more. One of the most well-known instances of it comes in 1592 when Raja Man Singh, after freeing the temple of Puri Jagannath from the clutches of Afghans, washed his blood-stained sword in the water of the sea at Puri.

Despite fighting for the Mughal empire Man Singh ensured the safety and prosperity of Hindu interests. It is because of this, he is still remembered fondly in Bengal and Orissa. Man Singh was a person of an incredibly complex character. Given the vulnerable situation he was in and the geographical weakness of his kingdom, he pulled marvellous feats in his name and saved dharma like no other king. He was a king who should be seen with honour and honesty rather than prejudice and treachery.

References:

[1] Lines are inspired by Herman Melville’s classical novel Moby-Dick

[2] A History of Jaipur by Sir Jadunath Sarkar Page 30

[3] Raja Man Singh of Amber by RN Prasad Page 08

[4] A History of Jaipur by Sir Jadunath Sarkar Page 45

[5] Purva Adhunik Rajasthan by Dr Raghubir Singh Page 55

[6] Mewar and the Mughal Emperors by Dr Gopinath Sharma Page 89-90

[7] “Bahlol Vadh” – Gordhan Bogsa

[8] A History of Jaipur by Sir Jadunath Sarkar Chapter 06

[9] A History of Jaipur by Sir Jadunath Sarkar Page 62

[10] A History of Jaipur by Sir Jadunath Sarkar Page 70

Leave a Reply