If the courts are truly concerned about animal welfare, they should first ban the killing of animals in all secular places and thereafter, enforce it upon religious places.

Ban on Paśubali – A Judicial Blunder (Part 1)

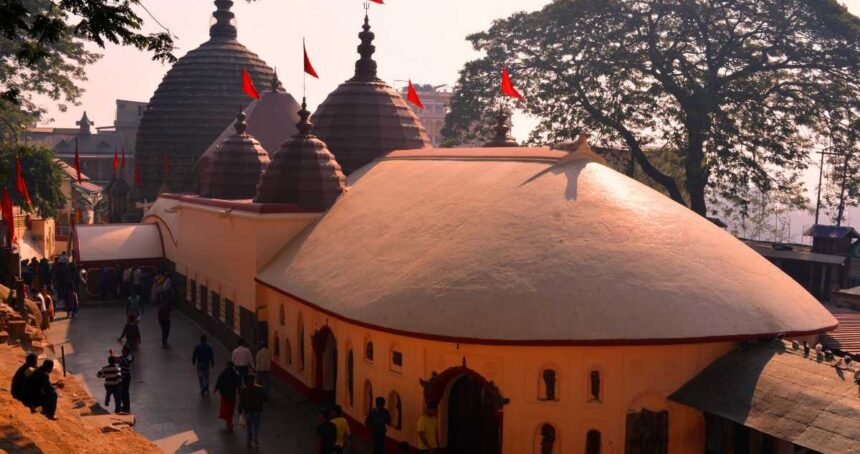

Recently, the Tripurā High Court banned paśubali (the sacrifice of animals and birds) in the Tripurasundari Mahavidya temple and all other temples across Tripurā. For now, in this part, I shall analyse the hollowness of this judgement and show how it is a judicial blunder. The next article shall establish, based on śāstra, that paśubali is an integral part of Śākta tantra together with the philosophical and spiritual questions surrounding it.

A Hollow Judgement

At the outset, let me point out in simple terms why this is a hollow judgement. We know that:-

- The laws of India permit the slaughtering of domestic animals for the consumption of their meat.

- In Sanātana Dharma, we should offer the devas what we eat.

From just these two principles, it follows that under Indian law, Hindus can offer meat to their devas. Note that here we are not saying that Hindus should offer meat to their devas. We are arguing against the judgement which says that under the Indian Constitution, Hindus cannot offer meat to their devas.

So the situation stands like this: Hindus can eat meat but cannot offer it to their devas. By plain logic, if such a judgement were to stand, it must violate either of the above two principles in some way.

For a moment, let us take the court’s side and try to violate these principles one by one:

- Violate (1). Hindus should not eat meat. Even if the Hindus were to plead for such a rule to be imposed upon themselves, the courts would find it hard to ratify this on a constitutional footing. So this cannot be legally enforced.

- Violate (2). Hindus cannot offer meat to their devas. Such a ban would be hard to practically enforce on an individual level. So restrict Hindus from offering meat to their devas in their common places of worship.

But this then curtails the religious liberty of māṃsahārī Hindus because they can no longer offer to the devas what they eat even in their common places of worship. So, if we just accept principles (1) and (2), we are forced to conclude that this judgement is a clear-cut case of an attack on the religious liberty of māṃsahārī Hindus.

Now, let us look at the validity of the above principles. Principle (1) is a fact, so it does not need any justification. Principle (2) is too innocuous to be objected to. Indeed, devotees eat only what they can offer to their devas. That principle (2) is an integral part of Hinduism is clear from śloka 27 of 9th adhyāya of Śrīmad Bhagavadgītā:

यत्करोषि यदश्नासि यज्जुहोषि ददासि यत् ।

यत्तपस्यसि कौन्तेय तत्कुरुष्व मदर्पणम् ॥

Note that we are using this śloka only to justify Principle (2). Hence, without even going into any of the details, we can see that this judgement is quite hollow. It cannot stand even such a simple argument.

Penny Wise, Pound Foolish

The judgement tries to ban an activity for religious purposes while still allowing it as an everyday practice. Had the activity been banned elsewhere and was still conducted for only religious purposes, the courts could have passed such a judgement. If the courts are truly concerned about animal welfare, they should first ban the killing of animals in all secular places and thereafter, enforce it upon religious places.

Articles 25 and 26 of the Indian Constitution, upon which the judgement is based, are additional guarantees on matters of faith and religion. These help protect the core parts of any religion so even if the killing of animals were banned in all secular places, paśubali would be allowed as it is an integral part of Śākta tantra, Note that these articles don’t take away any right that is otherwise present in secular activities. In fact, the contentions of the court regarding paśubali are more applicable to animal slaughterhouses.

Undoubtedly, this is a ‘penny wise, pound foolish’ judgement. But beyond the facade of constitutional morality, it is a direct attack on Hinduism and Śākta tantra in particular. The court didn’t deem it worthy to consider any Śākta text in any seriousness to understand the ritual and its significance. All they did was to consider some accounts by British officials of the colonial era. The judges made many moral judgements about the nature of God and religion and casually used many adjectives to describe a practice which they didn’t care to understand from original texts or from experts in the area.

Errors all around

They seemed quite eager to use their personal moral beliefs to justify their decision. In Section [119], they note, ‘They [the animal and bird] are also the creation of God.’ Which God are they referring to? And by which system of doctrine did they arrive at this conclusion? It seems that they are trying to impose their personal notion of morality and righteousness upon others. This is a dangerous trend.

The judgement also suffers from classical logical fallacies. In Section [100], it notes, ‘Not every devotee goes on to worship the deity in these temples by sacrificing animals. Evidently, this particular practice by tradition is merely optional and cannot be figured as an essential and integral part of religion.’ Consider an analogy: I toss a coin twice and I get two heads. Hence, ‘tails’ is not an integral part of the coin. This is a laughable argument. One should not comment on the integral features of an entity unless one has considered it in its entirety and not just, bits and pieces, here and there.

The judgement is also filled with self-contradictions. In Section [104], it says, ‘Hinduism includes Buddhist, Sikhs, Jainism and not every religion of Hinduism considers the sacrifice of an animal to be an integral and essential part of the religion.’ In the very next section, it says, ‘Major section of the community may believe in carrying out such practice in the name of religion but simultaneously, rights of co-religionists must be protected so as ensure that it does not hurt their sentiments.’ Why then are the judges imposing the beliefs of ‘Buddhist, Sikhs, Jainism’ on their co-religionists, the māṃsahārī Hindus and hurting the sentiments of the latter?

There are also many personal value judgements used to justify this decision. In Section [115], the judges note,

‘With blood of animals sprinkled around on the ground and the severed heads of the animals stocked in front of the deity, the view remains frighteningly dirty, leaving an impression of deficiency of holiness and peacefulness.’

Was there a survey conducted to reach this conclusion? Undoubtedly, this is not a universal fact since I have been to these temples many times and I found them neither ‘frighteningly dirty’ nor ‘deficient in holiness and peacefulness’.

A sad state of affairs

There are many other flaws I could point out but I rest my case with the following statement. This judgement shows the sad state of the Indian judiciary. This is unfortunate.

But what is perhaps more unfortunate is that many proud Hindus too didn’t spend much time understanding the significance of this practice and have assumed that their version of Hinduism, where such a practice is absent, is the only way. Absence does not necessarily mean opposition. And Hinduism has always professed the multitude of ways possible to reach the Ultimate.

Conclusion

To summarise, I think that this judgement fails even on basic logical grounds. But still, in my next article, I shall establish, based on paurāṇika, tāntrika and historical texts that paśubali is an integral part of Śākta tantra. I shall also address the relevant moral, philosophical and spiritual questions.

Continued in Part 2

Leave a Reply