“The control of Indian education is of so much importance that the necessity of gaining this would alone justify the present endeavours to attain political freedom.”

Introduction

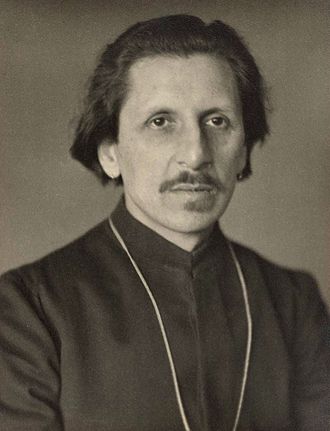

Ananda K. Coomaraswamy (1877–1947) is one of the greatest intellectuals of modern India, standing alongside the likes of Sri Aurobindo, Swami Vivekananda, and Rabindranath Tagore. He was a Ceylonese Tamil who had an English mother and lived most of his life in the West after his father’s early death. Coomaraswamy was a geologist, metaphysician, philosopher, linguist, art critic, and prolific writer.

A “traditionalist”, who understood Indian and Ceylonese cultures with an authority stemming from wide reading and knowledge of many languages, texts, and philosophies, he was severely critical of modernity and the dangers it posed to civilization. He was clear on the protection and preservation of traditions as a solution to civilizational continuity. Traditions, of course, do not mean a rigid ossification of past values but undergo organic changes in response to changes in circumstances. For him, the core frameworks of traditions were the key to world harmony.

He was a proponent of “Philosophia Perennis” (along with great thinkers René Guénon and Frithjof Schuon). A deep reading of scriptures from across all religions gave him an overview that showed the unity of all major religions in their essential messages. Whitall Perry, inspired by Coomaraswamy and painstakingly working for fifteen years, compiled a phenomenal anthology, A Treasury of Traditional Wisdom, consisting of thousands of quotations from the entire spectrum of spiritual traditions pointing essentially to the same Truth. The writings of Coomaraswamy, though a strong defence of Dharma, acted as a bridge between the cultures of the West and the East.

Remarkable prolificity and referencing are the hallmarks of his writing. Author of almost a thousand essays on the widest variety of topics, his many famous works include The Dance of Shiva and What is Civilisation? Many times, the extensive referencing not only exceeded the subject matter in length but was as interesting and illuminating as the main text itself. Apparently, a few references that Coomaraswamy quotes have been the basis for a lifetime study by some scholars!

Like Sri Aurobindo’s, his understanding of Indian social systems was deep. Both of them argued for the strength of Indian culture resting on the three quartets: the four varnas, the four ashramas, and the four purusharthas (Dharma, Artha, Kama, and Moksha). These three defined Indian culture and were responsible for India’s resistance to many physical and cultural invasions across the centuries. He was clear in saying that the “caste system” is not for apologising but for explaining. The identification of the most negative “excrescence of untouchability” with the entire culture (Sanatana Dharma = Hinduism = Caste system = untouchability; and thus, the solution for untouchability = dismantling Dharma) was a poor and mischievous understanding of India.

Coomaraswamy wrote on an overwhelming variety of topics, which perhaps would require a lifetime of study for any individual. This article is a summary and paraphrasing of three of his important essays on the English education of those times (Education in India; Memory in Education; and Music and Education in India). These three brilliant essays appear in the book Essays in National Idealism. Though written in 1909, the thoughts and ideas are still vividly relevant today.

The aim of this article is to stimulate readers to undertake a serious journey to the writings of Coomaraswamy, a person whose rediscovery means a lot to present India, confused by a mass of rhetoric eulogising the notions of “modernity” and progress. On the other hand, it is sad to realise that India had all the tools for a proper renaissance and rejuvenation back to its past glory in the form of the writings of Coomaraswamy and Sri Aurobindo at the time of independence. They expressed a solid grip on the strengths and weaknesses of India and not only that, they were aware of the possible solutions. Yet, for some inexplicable reasons, the builders of modern India ignored both of them.

Education in India

Coomaraswamy begins by saying:

“One of the most remarkable features of British rule in India has been the fact that the greatest injuries done to the people of India have taken the outward form of blessings.” Education, as devised by the English, was a striking blow to “almost every ideal informing the national culture“.

Most importantly, it destroyed all capacity for the appreciation of Indian culture. An ordinary graduate of an Indian University will know Shakespeare more than the Mahabharata and will have scarce knowledge about Indian music, religious philosophy, art, dress, or jewellery. “A stranger in his own land” who does not even know his mother tongue.

English educators believed Lord Macaulay, who said that a single shelf in a good European library was worth all the literature of India, Arabia, and Persia. Abbe Dubois (1765–1848) famously said, “To make a new race of the Hindus, one would have to begin by undermining the very foundations of their civilization, religion, and polity and by turning them into atheists and barbarians.” The English education had grandly failed to educate, that is, “to draw out or set free the characteristic qualities of the taught.” Merely to inform and not to educate, the English schoolmaster knows hardly anything of Indian culture and sympathises even less with Indian ideals. One cannot educate by ignoring the ideals of the taught and setting up an ideal that the taught does not at heart acknowledge. Accepting an alien formula for its material advantages assuredly destroys an indigenous culture.

He writes that the Government controlled all departments of education in India — primary, secondary, and university —directly or indirectly. Two-thirds of Indian Arts Colleges were Missionary Institutions, equally bound to government codes and selected textbooks. Modern education practically ignores Indian culture, which is essentially religious.

“Of the two types of English schools in India, Government, and Missionary, the former practise toleration — by ignoring Indian culture — and the latter practise intolerance by endeavouring to destroy that culture in schools. Tragically, the schools are not part of Indian life but are antagonistic to it…this education, which Englishmen are so proud of having ‘given’ to India, is really based on the general assumption — nearly universal in England — that India is a savage country, which it is England’s divine mission to civilize.”

The English teacher is ignorant of the language (rarely overcome) and is unfamiliar with the home life of Indians.

“The English Professor who arrives in India at the age of twenty-five is generally qualified to teach one or more special subjects, such as Chemistry, English Literature, or Greek. Ten years of sympathetic study of Indian religious philosophy, Sanskrit or Pali, some vernacular language, Indian history, art, music, literature, and etiquette might enable him to understand the problem of Indian education, probably would do so, prejudice apart; but the more he thus understood, the less would he wish to interfere, for he would either be Indianised at heart, or would have long realised the hopeless divergence between his own and Indian ideals; he would have learnt that true reforms come only from within, and slowly.“

But English teachers have neither the time nor the inclination to spend so much time, but they often rise to positions of power. Then, they cheerfully apply the solutions suited to an English environment to the conditions that they do not understand.

“The idea of education must be separated from the notion of altering the structure of Indian society — still one of the avowed objects of the Western educator.”

Education is the building up of character; it is a constructive process rather than destructive. The educator himself may be the origin of the destruction! They, with pain and labour, have destroyed the social fabric by being thoroughly convinced of the superior value of European ideals. The ideals of Indian civilization are actually higher than those of any other; even if it were not so, it would still be true that only by means of those ideals can one educate India. In the words of Sir Henry Craik, it is necessary to abandon “the senseless attempt to turn an Oriental into a bad imitation of a Western mind. It is not a triumph for our education — it is, on the contrary, a satire upon it — when we find the sons of leading natives expressly discouraged by their parents from acquiring a knowledge of the vernacular.”

What then are the essentials, from the Indian point of view, that, for their intrinsic value and in the interests of the many sides of human development, are so important to preserve?

- Firstly, the almost universal philosophical attitude contrasts strongly with that of the ordinary Englishman, who hates philosophy. Science is important, but there are wrong and right ways of teaching it. ‘Facts’ taught in the name of science are a poor exchange for metaphysics.

- Secondly, the sacredness of all things — the antithesis of the European division of life into sacred and profane. European religious development excludes from the domain of ‘religion’ every aspect of ‘worldly’ activity. Science, art, sex, agriculture, and commerce are, in the West, secular aspects of life, quite apart from religion. In India, this was never so; religion idealises and spiritualises life itself rather than excludes it. This intimate entwining of the transcendental and material explains the strength and permanence of the Indian faith and demonstrates not merely the stupidity but the wrongness of attempting to replace a religious culture with one entirely material.

- Thirdly, the true spirit of religious toleration is illustrated continually in Indian history and is based upon a consciousness of the fact that all religious dogmas are formulas imposed upon the infinite by the limitations of the finite human intellect.

- Fourthly, etiquette — civilization conceived of as the production of civil men. A Sinhalese proverb says, “Take a ploughman from the plough and wash off his dirt, and he is fit to rule a kingdom.” There would thus be no difference between the ability of speech of a countryman and a Courtier in an education that focuses on this etiquette.

- Fifthly, special ideas in relation to education, such as the relation between teacher and pupil implied in the words of guru and chela (master and disciple); memorising great literature, the epics, as embodying ideals of character; learning not to become a mere road to material prosperity; and the extreme importance of the teacher’s personality. This view is antithetical to the modern practise of making everything easy for the pupil.

- Sixthly, the basis of ethics is not any commandments but the principle of altruism, founded on the philosophical truth: “Thy neighbour is thyself.” This is a recognition of the unity of all life.

- Seventhly, control, not merely of action but of thought; concentration, one-pointedness, and capacity for stillness.

These intrinsic components of Indian culture must form the basis for a sound educational ideal for India. The aim should be to develop the people’s intelligence through the medium of their own national culture and local vernacular. The national culture is the only vantage point from which a person can take a wider view of other cultures.

“Western knowledge is necessary for India, but it must form for her (and especially for her women) a postgraduate course. England can now render only one true service to the cause of Indian education by placing the education budget and the entire control of education in Indian hands. It will be for us to develop the Indian intelligence through the medium of Indian culture, and building thereupon, to make it possible for India to resume her place amongst the nations, not merely as a competitor in material production but as a teacher of all that belongs to a true civilization, a leader of the future as well as of the past.”

Memory in Education.

In this essay, Coomaraswamy stresses the importance of training memory, the most conspicuous feature of Indian education that the English education system obviates. Religious literature, music, history, and technical knowledge were handed down orally from one generation to the next. He says that the national cultures in the East only secondarily connect with books and writing.

The Sinhalese proverb, “Take a ploughman from the plough and wash off his dirt, and he is fit to rule a kingdom,” implies the civility, understanding, and gravity of the poorest, unconnected to the capacity to read and write.

Coomaraswamy cites the example of the common folk of Ceylon who would do their daily tasks singing the tales of Vessantara, Jatakas, Yasodhara, Padmavati, Buddha, or Gaja Bahu. This demonstrates the existence of a common culture independent of the written word. In the past, even the illiterate were familiar with legendary verse and ancient literature, and this general acquaintance produced a seriousness and dignity of speech unknown to the present-day youth.

Coomaraswamy writes:

“In Ceylon, the old culture, especially in the up-country villages, is however passing away, and is partly due to the competition of Government and Mission schools, partly to the decay of Buddhism, partly to the general indifference to the importance of vernacular education. Those who have been… in an ordinary English school are usually very ignorant of the geography, history, and literature of Ceylon.“

Coomaraswamy says that even Western authors like Yeats rue that “Irish poetry and Irish stories were made to be spoken or sung, while English literature, the newest of them all, has all but completely shaped itself in the printing press… ”

The old system had its faults, no doubt, the most obvious being a slightly deficient development of the reasoning faculties and excessive reliance upon authority and precedent. Yet, it did not divorce the “educated” from their past nor raise an intellectual barrier between the upper and lower classes like the new systems. Coomaraswamy says that the present examination system is also a memory system, albeit inferior, because this learning is only a temporary storage of facts. Degrees become more important than learning a subject for its own sake.

English education, says Coomaraswamy, is lifeless even in England, where one learns far too many subjects and forgets easily without reaching “culture”. Imagine what this education becomes when imposed on the East. Though difficult, it would be more effective if Indian educational ideals became a scheme for developing the people’s intelligence through the medium of their own national culture and vernacular. “English” education in the East appears to crush all originality and imagination in its students. There is nothing surprising about the poor quality of graduates when they learn foreign subjects in a foreign language in complete ignorance of the indigenous culture. An important part of the Empire’s responsibility is towards the already existing culture and ideals of the subject peoples.

Even science is not everything. “Science is a poor thing without philosophy, and philosophy was an inseparable part of the old culture.” The idealism of the Upanishads, permeating all Indian life and thought, lies at the roots of all religion and philosophy. This idealism, continually re-expressed in all Indian, including Buddhist, literature, is in marvellous agreement with the philosophies of Parmenides, Plato, Kant, and Schopenhauer.

The genius of the old culture was that culture came to a man at his work; Coomaraswamy opines;

“it was an exaltation of life, not something won in moments stolen from life itself. And one way in which this came about, perhaps the best and most universal way was through the literature; and that literature was mainly orally transmitted, that is, it was very much alive; it belonged both to the illiterate and to the literate; it expressed the deepest truths in allegorical forms which, like the parables of Christ, have both their own obvious and their deeper meaning, and the deeper meaning continually expressed itself in the more obvious, and both were beautiful and helpful. The literature was the intellectual food of all the people, because it was really a part of them…large and deep enough for the philosopher, and simple enough to guide and delight the least intellectual.”

Coomaraswamy writes that Indian life lives in the light of the tales of India’s saints and heroes. The two great Indian epics and Puranas have been the great medium of Indian education, the most evident vehicle of the transmission of the national culture, and the basis of real character building across generations. Likewise, the Buddhist culture in Ceylon revolves around the stories of Buddha. It is this common culture that modern English education ignores and destroys. The memorization of great national literature was the vehicle of this culture, hence the tremendous importance of memory in education. The Ramayana, Mahabharata, or Jatakas are not meant as examination courses. They are a means of the development of imagination and character — a faculty generally ignored and sometimes deliberately crushed by present-day educators.

Memory, in the Indian view, is in itself a most important part of personal character, especially associated with the ideas of self-control and mental concentration. In fact, the method of noisy repetition in the village schools improves memory and concentration. Psychology is, for India, the synthesis of all the sciences. All knowledge bases itself on knowledge of the self. Only by the power of concentration can this “self” come under control and focus.

“The story of Arjuna focussing on the bird’s eye embodies the culminating ideal of the nation, as concentration of mind stands among Hindus for the supreme expression of that greatness which we may recognise in honour or courage or any kind of heroism.“

Thus, a real responsibility rests upon those who control education in the East to preserve in their systems the fundamental principles of memory training and mental concentration, which are the great excellences of the old culture. However, this responsibility rests with Indians only and not with any foreign educator.

Music And Education In India

Ananda Coomaraswamy had a deep knowledge of music and art, and in this fascinating essay, he makes a plea to integrate Indian music into the curriculum in a more emphatic manner. Music is the carrier of culture, and Coomaraswamy agonises over the replacement of Indian music with the piano, harmonium, and Western music. He says that the Government, missionaries, and Anglicised Indians, in their educational policies, refused any responsibility for the past. The consequent break in the continuity of the historical tradition built carefully by the ancients is fatal to Indian culture.

Plato says, “Rightly studied, music has all the exactness of pure reason and science, all the expansiveness of the imaginative reason, all the metaphysic of the profoundest philosophy, and all the ethic of the purest religion in it… It is an energy of the mind in the first instance… Music, properly taught, includes all that is generally conceded to belong to a liberal education.” These ideas, Coomaraswamy says, are far more clearly recognisable in Indian culture than in English culture.

No educational institution gives place to Indian music. European educators have neither knowledge of Indian music as a science nor appreciation of it as an art; the majority regard it as noise. This is a typical instance of the unfitness of Englishmen to control Indian education, both by lack of knowledge and by lack of sympathy. Teaching European scales and songs to children capable of using the more elaborate scales of the East makes Indians lose the power of appreciating their own melodies. The execution scarcely ever reaches a high level, and they cannot afford expensive instruments like a piano at home. They end up despising the “inferior” taste of their folk at home, for whom European music is meaningless.

Modern English education in India contemplates music essentially as an accomplishment. One defence is that by introducing western music, a student can “enjoy” both types. However:

“Music and art are not amusements invented by idle men to pass away the time of other idlers; they are expansions of personality, essential to true civilisation, expressions of the human spirit, confirming the sincere conviction that man does not live by bread alone. Music, even more than plastic art, is a function of the higher consciousness. The true musician is…the Indian singer who hears the voices of gandharvas.”

If art and music are thus self-expressions of the culture, obviously imitation from other nations whose environments are different results only in vulgarisation.

“Western culture may be, and will be, of value to the East, but it must be as a post-graduate course — it will not stand in the place of mother milk. We cannot understand others by ceasing to understand ourselves.”

The eager Indian elite, trying to be progressive and enlightened, believes that it belongs to an inferior race with few traditions worth preserving. In India, music is not only for the wealthy virtuoso; it is a part of national life. It is still an art, not an accomplishment or an intellectual exercise, in the hearts of the people. An education based upon a foreign culture can only produce “accomplishments” but cannot give the means of creative self-expression, possible only in the mother tongue, whether in speech or song.

The gramophone, the harmonium, and the cheap, ill-taught piano stand in India for European music. This is not to say that Indian music must not change in any way because of changed conditions, but that such change must be organic, not sudden, and that it must be an evolution in accordance with the bent of the national genius. The object of education must be to make good Indian citizens, and this is possible only by using the national culture and the national languages (literary, musical, and artistic) as the medium of instruction.

No school of music has arisen and flourished in modern Europe without a basis in national folk music expressing national aspirations and ideals. Russia is a prime example. Religious songs, songs of agriculture and crafts, songs of the love of the land, and folk songs must play in every school. “India should realize that we have neglected the vital music living in the hearts of peasants, uneducated and illiterate—but more truly Indian than their ‘educated’ superiors“. In India, there is no divorce between folk music and art music, which, like the distinction between decorative and fine art, is such an unfortunate feature of European culture.

These are the days of nation-building. The nationalists want to be free and compete with Europe to gain political power and material success.

“The future of India does not lie with them but lies in the lives of those who are truly Indian at heart, whose love for India is the love of a lover for his mistress, who believe that India still is the light of the World, who to-day judge all things by Indian standards, and in whom is manifest the work of the shapers of India from the beginning until now.”

No Indian can be a true citizen of the world except by first being an Indian citizen and, from that standpoint, entering into the life of humanity outside of India. Education in Indian music is an essential part of this education in Indian citizenship.

Oriental art, music, and literature have been for audiences far more cultivated in respect of imagination and sympathy than the audiences appealed to by the musician in the modern West. This depends, in turn, on a common national culture. The artist relies on his audience to understand his refinements and suggestions. This does not happen now because of the separation of education from real life and the desires of the people. Coomaraswamy hopes that Indian folk and art music, properly placed in Indian education, will make people understand that the national self-expression is in her music. Civilization finally fails when its people are ashamed of their own music or even of their own language.

Concluding Remarks

These three remarkable essays are a marker of the genius and depth of Ananda Coomaraswamy. His thoughts on education are as relevant to India today as they were more than a century ago. We have not been able to decolonize ourselves even after so many decades, thanks to some incredible education policies after independence. As Professor Bhikhu Parekh points out, Nehruvian policies stressed higher education for forging national unity, ignoring primary education and cultural heritage as enduring bases for national unity. The ignoring of primary education led to a huge variety of schools with little coordination, no coherent framework of objectives, limited relevance to Indian conditions, and poor attempts to ground pupils in Indian history and culture. The future citizens of India grew up with little in common, sometimes sharing the minimum of memories and values with their parents. In some English-medium schools, the products were a confused mix of the West and India.

The other policies, like nurturing a “scientific temper,” were simply a collective failure of Indian political thinkers and academicians to look at the nature of Indian past and traditions. Extraordinarily, the assessment of the 150-year colonial rule of at least a five-millennium-old civilization became a benchmark for us. They were ignorant of the enormous contributions Indians made in the fields of science, technology, and the arts (arithmetic, algebra, calculus, astronomy, metallurgy, biological sciences, literature, town planning, sanitation, ship-building, and architecture, to name a few). They could not realise that science could flourish in different frameworks of understanding the world. The colonial view of a primitive and barbaric India devoid of scientific achievements eerily sticks with most Indians today.

The single most damaging factor in our education was perhaps the distorted application of secularism in India. Secularism and the separation of the “sacred” from the “profane” were straight imports of European ideas battling their religious issues. Classifying the most wonderful philosophies and metaphysics available in our Vedas, Upanishads, Darshanas, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Bhagvad Gita, Puranas, and countless other texts as “religion” and then excluding them from study at the school level for the sake of secularism has been the single most important cause of the lack of pride in our culture.

Our thinkers even did not aim to find out what “religion” actually means or whether the traditions of India, with their huge corpus of texts, have anything to do with religion in the first place. Secondly, do they not belong to every Indian, irrespective of language, region, varna-jati, or faith? Secularism was good for “minorities” as a temporary measure, but it has done intense damage to the fabric of the country, held together so beautifully till now with cultural-spiritual bonds.

Where does “colonial consciousness” work? SN Balagangadhara says it is everywhere. We perpetuate the themes told to us about ourselves by the English: The Aryan story; the conversion of Indian traditions into religions and then accepting secularism as the best solution for harmony; the superimposition of caste, a western idea, into the varna and jatis of India; solidifying politically and legally a rigid hierarchical “caste-system” at divergence from the socio-cultural practises; a disdainful view of traditional medicine; the need for the English language to prosper and also as a national language; a “historical” reading of our texts and scriptures; accepting the idea of one dharmashastra (Manusmriti) as prescriptive and authoritative for all eternity to come; making the western clash between “science and religion” our own; understanding our practises and rituals from a “scientific perspective” and making them superstitious and irrational; the story of the “revolt” of Buddhism; the disbelief in a golden period of India that attracted plunderers from across the world; the story that we were never a nation and the British united us; ad infinitum.

One famous quote by Ananda Coomaraswamy says:

A single generation of English education suffices to break the threads of tradition and to create a nondescript and superficial being deprived of all roots — a sort of intellectual pariah who does not belong to the East or the West, the past or the future. The greatest danger for India is the loss of her spiritual integrity. Of all Indian problems, the educational is the most difficult and most tragic.

This is unambiguously still relevant to India, with its acceptance of both the English language as the major medium of instruction and secularism as the guiding principle of our curricula.

Leave a Reply