Plot:

A middle-aged woman and scriptwriter, finds herself questioning certain life decisions when her father passes away. Her name is Laxmi, although she changes it to Razia when she marries her college sweetheart, who insists that she convert to Islam as a mere formality. Her father chose to cut off ties with her and it is only years after his death, does she begin to long for the faith of her birth. In the process of rediscovering her Hindu roots, she also learns more about a certain section of Indian history that deals with the violent Islamic conquests and conversions. No longer as convinced by the revolutionary zeal of her early youth and finding no succour from her progressive beliefs, this novel is as much one that deals with her quest for historical truth as it is a woman’s journey of self-discovery and reconnecting with her roots.

The author uses a rather interesting literary technique to highlight the ravages and pain of the Islamic onslaught and violence. I’m referring to that of a novel within a novel or a story within this very fictional story. The perspectives in the novel switch between Laxmi/Razia and her fictional character, a Rajputana prince. We also occasionally have passages dedicated to her husband Amir’s, and her mentor Prof Shastri’s point of view.

The following contains multiple spoilers so please read on only if you are comfortable with that.

Themes and other topics of interest:

- Portrayal of the Islamic conquest of Bharat:

This is a prominent theme across the book as it deals with the harrowing details of the violent Islamic conquest of Bharat. Although there are occasional references to the general treatment of Hindus under Islamic occupation, most of the events are narrated in the first person by a victim of conversion. Laxmi pens down the above story of a Rajput prince who chooses to convert to Islam while his other family members perish in an armed confrontation against marauding invaders. The prince’s story is heartbreaking as we read events of him being subject to sexual humiliation to being forcibly castrated and then finally, sold into slavery as he passes through the hands of multiple masters. The author has managed to convey the emotional depth, his turmoil and pain throughout the ordeal very convincingly. The reader is privy to his life as a member of the Zenana/Women’s quarters in a traditional Islamic household. He learns much of Islam and begins to despise his native faith, especially after he feels that his Kula Devata, Vishnu Ji did not protect him. Instead, he had to witness the moorthi being smashed to bits in front of his eyes. Another historical event is also featured. The demolition of the original Kashi Vishwanath temple under the orders of Aurangzeb, makes for a harrowing read. The ending is somewhat inconclusive. In some sense, it is historically faithful and doesn’t give the reader false hopes of a happy ending. Yet, I wouldn’t have minded reading more of this story as there was a lot of untapped potential here. - Depiction of contemporary academics and activists from the humanities domain:

The scenes preceding the novel’s denouement perfectly embody the above. It features a seminar of sorts that academia members, media professionals and other creative artists are invited to attend. Laxmi/Razia is also invited to this seminary of ‘progressives’ that is designed to discuss how to further distort history couched under the garb of maintaining ‘communal harmony’. It is clear that the views of all in lieu are homogenous and there is no scope for varied opinions. There is to be widespread dissemination of the agenda in the literary, media, and academic spaces. When anyone tries to dissent, they are actively sidelined and prevented from taking part in future seminars. Despite attending multiple such events back when she shared their ideological beliefs, Laxmi now finds herself unable to remain silent. She courageously counters all the factual inaccuracies and downright lies that are aired by the ’eminent intellectuals’ and does so with aplomb. The years of painstaking research she has spent documenting the extent of Islamic iconoclasm in Bharat, the copious amounts of notes she has made, and all the work put in to gain a comprehensive grasp of history finally see the light of day. She vanquishes her opponents and despite her (and the reader) knowing the inevitable conclusion i.e. her imminent banishment from the coterie, one can’t help but cheer her on. The portrayal is also superbly personified through the character of Professor Shastri. He is an acclaimed member of the ‘progressive’ cabal and an academic of the humanities department. He is depicted as many of his real-life counterparts are – glibly persuasive, charismatic and more focused on pushing agendas and distorting history than portraying the truth for what it is.

The resemblance to real-life events is uncanny and one wonders if the author is drawing from his own life experience. It is well known that his works have been boycotted by the ‘progressive’ establishment and he has been unfairly branded as a religious ‘fundamentalist’. The title ‘Aavarana‘ here refers to the act of concealing the truth by Marxist historians. Given that such skewed depictions continue to be peddled with impunity, it is clear that the issues raised in the novel are still relevant. This, despite this novel being published 16 years ago (in Kannada) and 9 years ago in English (translation). - The supposed Shaiva-Vaishnava conflict:

This was brought up in the context of Vijaynagar-Hampi and other Southern districts that had felt the brunt of Islamic Iconoclasm. In the novel, Amir and Laxmi/Razia get into a discussion that quickly grows heated. They are at Hampi and have been commissioned to film a documentary featuring its history and the mutilated moorthis. Amir comes up with all kinds of strange theories and tries to project Marxist paradigms. He claims that the artisans had been suppressed by the feudal lords and therefore, took the side of the neighbouring Vaishnavas who came to attack the Shaiva rulers. When their pent-up resentment reached its zenith, they let forth their rage and destroyed the very moorthis they had painstakingly built in the first place! Laxmi quietly proceeds to dismantle the ludicrousness of his argument. She points out that for the Shaiva artisans, it wasn’t just limited to earning a living but their Dharma. By carving out intricate Moorthis, they were also paying obeisance to the deities that they so dearly loved and worshipped. How then can one believe that they would go against their own beliefs and savagely destroy them regardless of whether they felt ill will towards their employers? (Which may simply be speculation). Regarding the animosity between the sects of Shaivas and Vaishnavas, there was no doubt that conflicts did arise, and tensions were present. But it never took the form of iconoclasm or reached a point wherein either proceeded to demolish moorthis with the savagery that the Islamic marauders did. Even a basic knowledge of the latter is enough to tell a child that such actions stem from the latter’s hatred of ‘idol worshippers’ and intolerance against multiple deities that they label as ‘false gods’. The book includes a list of kings from one sect who presided over the building of temples of the other sect. Even if desecration was present, they were few at best and a clear instance of aberration. Unlike Islam where annihilating pagan-pluriversalism and demolishing moorthis is the norm and more importantly, is sanctioned by their scriptures. - The Kashi Vishwanath temple and Gyanvapi Mosque:

The revered city of Kashi has always attracted Hindus from all corners of Bharat who are steadfast in their belief that staying there, and bathing in the waters of the holy Ganga frees us from this miserable cycle of birth and re-birth in Samsara. Imagine nursing grand hopes of visiting a grandiose temple as expected of a sacred sthana only to see it being eclipsed by a huge monstrosity. I’m referring to that which has been built on the foundations of Islamic iconoclasm. The actual place of worship is quite small while pilgrims are instead greeted by the Gyanwapi mosque. The author has managed to accurately depict the disappointment, pain and resignation that pilgrims undergo upon getting the first glimpse.

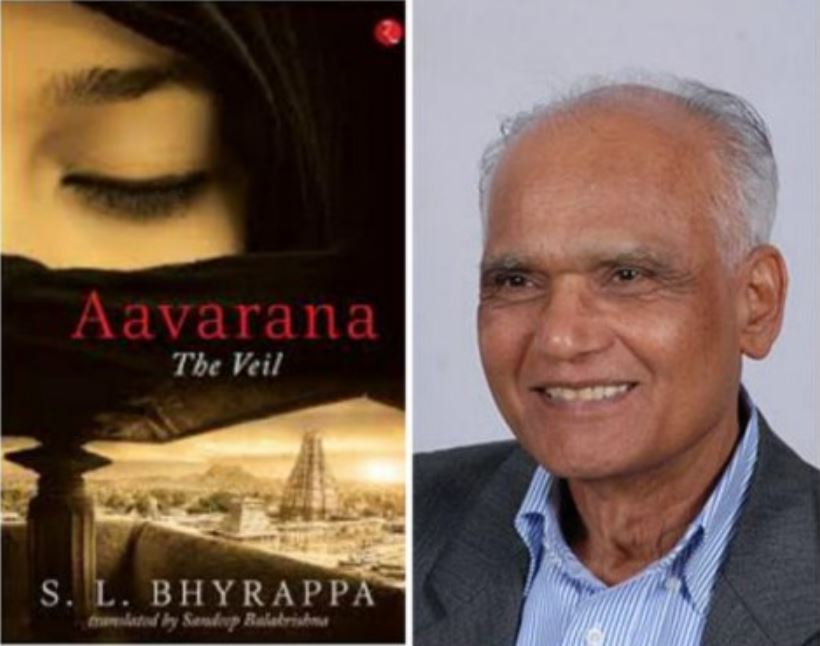

Chapters about the Kashi Vishwanath temple alternate between Razia/Laxmi visiting Kashi in the present time and also the fictional narration by the Rajput prince that jumps back in time to when Aurangazeb ordered its demolition. Whilst reading certain passages, it almost feels as if the reader is standing witness to the events unfolding. Notwithstanding the painful subject matter, the author’s skill and prowess at conveying such emotionally gripping scenes must be commended. Credit must also go to the translator Sandeep Balakrishnan, who has faithfully adapted the original from Kannada and rendered it in very readable (and excellent) prose.

Characters:

- Laxmi Narasimha Gowda Alias Razia Begum:

A spirited young woman who was quite the revolutionary ‘progressive’ in her early youth. As the daughter of a staunch Gandhian, she finds herself adopting and then abandoning belief systems throughout her life. First, it was the Hindu cultural customs and traditions she was born into and raised with. Then it was the Marxist beliefs of ‘feudal landlords vs peasants’ that she adopted in college as a young adult. These were complemented by her idealistic notions of love between a man and woman when she was infatuated with her present-day husband. This union led to her adhering to the rigid tenets of Islam and discarding her faith of birth. She then began to doubt Islam and reconnected with her Hindu roots after her father’s demise. This also coincided with her quest for the truth of Bharatiya History, wherein she gradually morphs into a more detached observer of history. She is the novel’s primary protagonist and narrator. She is courageous, willing to re-examine her beliefs and question previously held notions, a strong seeker of the truth and also, sensitive as most creatives and artists tend to be. A fitting heroine who makes a mark, despite the novel touching on sensitive subject matter and other interesting characters. - Prof Shastri:

A lascivious and morally bankrupt professor who has no qualms when it comes to suppressing historical truths of Bharatiya history. Despite his charisma and powers of persuasion, he is a glib and dishonest scoundrel. There are passages in the novel that deal with the nature of academia (the humanities domain at least), the charade they put up and even the nitty-gritty interrivalry or competition and backstabbing, amongst members of the same ideological fraternity. These are all narrated by Professor Shastri and the author’s depiction is an accurate one, what with his fiery speeches that are high on emotive appeal but low on historical accuracy.

His conduct in his private life is just as bad as his professional behaviour. Despite being married, he frequently makes passes at Laxmi (and presumably other younger women as well). All this is done while engaging in casual greetings like hugs, wherein he frequently manages to go beyond the usual pleasantries and makes his female companions uncomfortable. The power dynamics of an older man/senior mentor figure and younger and more impressionable women are very accurately and subtly portrayed. It’s not some uni-dimensional portrayal of a vile man who abuses his younger female colleagues or students; it’s more subtle. Given his charisma and degree of power (an eminent intellectual) there is quite a bit he manages to get away with. I was uncomfortable reading passages wherein he makes physical advances towards Laxmi, extends hugs into something more, is never above making inappropriate comments and continually tries to establish some kind of intimacy with his sleazy declarations of closeness. - Amir:

He is Laxmi’s college lover and life companion. A supposedly ‘progressive’ man, he finds himself succumbing to the more rigid tents and customs of Islam when under pressure from his family and community members. He is a documentary filmmaker and the duo work well together, with Laxmi being the scriptwriter who is well versed in penning down excellent dialogues both in Kannada and English. The depiction of romantic dynamics between husband and wife, who also collaborate as creative artists is as nuanced as the depiction of their crumbling marriage. Despite proclaiming to be a progressive ideologue, he still adheres to certain rigid beliefs of his faith. He insists on Laxmi converting to Islam as a mere formality (at first) but increasingly insists on more conformity, as his religious Muslim parents insist. Throughout the novel, Laxmi and Amir have many discussions about the violent nature of Islamic occupation and the veracity of versions peddled in mainstream depictions. Their interactions grow increasingly acrimonious over time. It had started when the government had wanted them to produce a series of documentaries that portrayed Tipu Sultan in a favourable light while glossing over his bigotry, fanaticism, violent conquests and conversions. Laxmi’s study of primary sources of history increasingly convinces her that she can no longer distort history as she did in the past. Amir does not respond favourably to her discoveries. As she begins to unearth the truth, it naturally takes a toll on their marriage particularly since Razia/Laxmi had not had a problem dishing out the same drivel on previous occasions. The novel doesn’t cover the early years of their companionship but introduces readers to them when both are middle-aged. She begins to question the revolutionary beliefs and conditioning she has been brought up with and slowly reconnects with her Hindu roots. This was probably triggered by the death of her father who had cut off ties post her marriage and conversion to Islam. As Laxmi begins spending more time in her father’s home discovering the copious amounts of research he has undertaken on Islamic conquests in Bharat, she finds herself spending less time with her husband. During periods of separation, they do have short bursts of reconciliation, only to then have it be interrupted by a fresh bout of animosity. Amir even goes so far as to try divorcing her. Although, he begins the proceedings by giving her a triple talaq, he doesn’t complete it. Much later, when Laxmi spends most of her time in her father’s village, he marries a much younger Muslim woman from his own community. It’s worth noting that polygamy and instant divorce are prerogatives granted to males of the Islamic faith.

Addressing Criticism Levelled against it by detractors.

One of the common criticisms levelled against the book by both ideological adversaries and allies alike is that the characters feel more like caricatures. While the adversaries were more vitriolic in their critique of course, both agreed that they were somewhat unidimensional and not fully fleshed out. I’ve spent a great deal of time trying to see if there’s some truth to these views. Although I agree that it is indeed applicable to the minor characters (Nadir, Aruna and the unnamed English-Catholic wife of Professor Shastri) it is untrue for the more prominent characters: Laxmi alias Razia, Professor Shastri and Amir.

Some want to reduce these characters to mouthpieces for the author’s views on a whole host of topics: some highly sensitive and others not so. I think the above reduction does a disservice to the author’s creative prowess and writing abilities. A test I subject fictional characters to, to ascertain if they are indeed fully formed beings is to analyse their interpersonal dynamics with other characters. To see if the nuances of their relationships have been accurately portrayed. In this case, I think they are.

Let’s start with Amir. The author spends a fair amount of time documenting the decaying relationship between Amir and Laxmi. The latter reconnecting to her Hindu roots and study of history begins to drive a wedge between them. At one point they begin living separately and Amir grows lonely, sexually repressed and longs for physical intimacy of some sort. It is here he succumbs to community pressure and marries a much younger girl who is from an orthodox Muslim family. Later he begins to repent of his second marriage while remaining legally bound to Laxmi. He misses the rapport they shared, the intellectually stimulating conversations they had and their shared creative vision, with which they brought many documentaries to life. There is a scene towards the novel’s conclusion wherein he confronts her in a hotel, where both are invited to a conference. They converse privately when he trods up to her room in a bit of a drunken stupor. In this state of inebriation, he is more vulnerable to openly admitting certain truths to Laxmi which he otherwise would not. He honestly tells her that he missed her, only went through the second marriage out of loneliness and this new wife cannot match her in personality or intellect. He is even willing to divorce the second wife so that they can reunite with one another. The depiction of life companions that once loved one another and still retain a certain degree of affection for each another is a convincing one. There are occasional instances in the novel where she recalls the early days of their courtship. I bring this up only to prove that the Amir character was not a mere caricature, and the author has painstakingly depicted the dynamics between the duo.

The same applies to Prof Shastri albeit to a lesser extent. While some found the sudden switch to his perspective in the novel’s mid-section to be needless, I found it interesting. Perhaps it did not add to the novel’s overarching goal which was to convey the brutal realities of the Islamic occupation of Bharat and the quest for the truth of Indian history. But it was still well depicted. We have moments wherein the Professor is furious that rivals in academia are out to defame and bring him down (despite them publicly sharing the same set of ideological beliefs). There are other moments wherein he expressed his frustration that his son was in touch with his estranged father, was eager to honour his Hindu traditions and withheld informing him of the above. This despite him being an avowed communist whose progressive credentials required him to discard religion as ‘the opium of the masses’. Some may find the subplot of him trying to clandestinely perform his mother’s final funeral rites to be superfluous and I do agree that some parts could have been omitted. Yet for all that, it is a nuanced depiction that can hardly count as a caricature or ‘cardboard cutout’. His lascivious nature, tendency to make passes at women and be more physically ‘touchy’ than necessary only add credence to the portrayal. Not a likeable character but certainly a believable one. It is clear that he is modelled after certain senior males and ‘progressive leftist academics’ who need lessons in propriety, especially when it comes to behaving around women.

Valid Criticism:

We now come to the minor characters. Nadir, Laxmi’s son most definitely did feel like a caricature. He is depicted as being a rigid adherent of Islam who is very religious and has no understanding of his mother’s native faith. The dynamics between him and his mother were not as convincing as the previous set of dynamics between Laxmi-Amir and even Shastri interacting with family and rivals. The introduction of the character Aruna was also pointless as was the character of Shastri’s European wife who was a very shadowy figure at best.

Aruna is the daughter of Professor Shastri and has been raised Catholic by her British Christian mother. The subplot that features her narration of experiences felt contrived, almost as if it were deliberately inserted to portray Christianity in a poor light. It’s not that the points raised in the above saga weren’t valid. It is true that there is an ingrained sense of superiority Abrahamic faiths allow their adherents, to consider man above all other living creatures; Nature’s existence is only to ‘serve’ human desires and needs. This flies in the face of Santana Dharma which acknowledges that humans are only one tiny part of the entire cosmos. Animals and other living beings do not solely exist for their sake and exploitation. But the characterisation felt more like a treatise than the organic flow of events in a fictional novel. The brief vignette of Aruna being enamoured by Hindu culture, traditions and customs could have been further explored. In addition, one wonders if the only reason for her conversion to Islam was because (as the novel suggests) she was ‘sexually repressed’ as a late twenty-something woman and was attracted to the ‘virile Nadir’. These characters and subplots could easily have been omitted with the focus being solely on the history of Islamic conquest in Bharat and the current-day whitewashing of their past atrocities.

Despite liking the story within a story element and several other sections of the novel, I must admit that parts of it do read more like an ideological treatise than a work of fiction. Some passages are blatant wherein the characters could easily be misconstrued as being mouthpieces for the author’s ideological beliefs. While I do not object to the portrayal of the Islamic occupation of Bharat as being violent, for it is the truth, I do wonder if the conversations where the merits and demerits of Hinduism and Islam are compared and discussed could have been more balanced and less pointed.

Moreover, there is an unsubtle depiction of Hinduism as comprising non-violence, ahimsa, vegetarianism and to a much lesser extent, celibacy. This is seen in the way the primary protagonist, Laxmi alias Razia’s father is portrayed as a staunch Gandhian who adheres to some of Gandhi’s distorted understanding of Hindu Dharma. It is also evident in the conversation between the fictional characters of Laxmi’s novel about the Islamic onslaught. A converted Rajput prince and a Hindu Sadhu are conversing on the banks of the river Ganga. The Sadhu shares many interesting insights, while comparing Hinduism and Islam. Some of these include the limitations of Monotheism, how immature it is for a jealous God to disallow worship of other multiple Gods, the nature of evolved religions and much more. The above are admirable but occasionally there are references to glorifying vegetarianism. Even in conversations between Laxmi alias Razia and her husband Amir, this comes up regularly wherein vegetarianism and abstaining from animal killing is heavily praised when compared to Islam. I’m unsure if the characters here are representative of the author’s views. In addition, Bali Vidhan or animal sacrifice doesn’t seem to be portrayed in a favourable light despite its spiritual sanction. The pacifistic streak and glorification of vegetarianism may be objected to by some readers, who don’t find it to be an accurate portrayal or representation of Hinduism.

In conclusion, if one of the objectives of the book was to inspire readers to learn more about Bharatiya History and to question what we have been taught as sacrosanct in school history textbooks, then it has accomplished its job.

An excellent work of fiction and one I heartily recommend.

Final Rating:

4/5 Stars

Leave a Reply