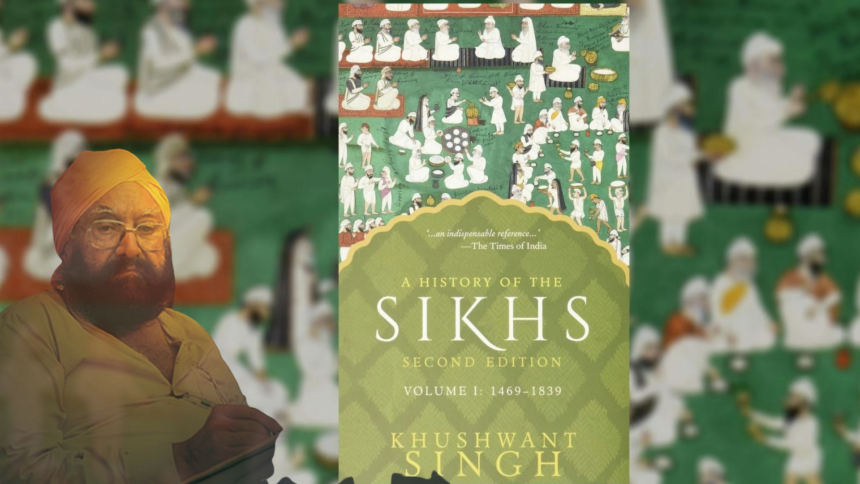

Arguably the most popular resource for reading Sikh history is the two-volume book “A History of the Sikhs’’ by Khushwant Singh. Sponsored by Aligarh Muslim University and Rockefeller Foundation, the first Indian edition of the book came in 1977. The book is ambitious in its scope and covers a period of around 370 years in detail (1469-1839). In the introduction, the author gives a brief overview of Punjab’s history, geography, and climate. To begin with, he uses Guru Nanak’s beautiful composition, “Bara Maha” to describe the different seasons of Punjab.

Once the milieu of the book is set, the author explains how Sikhism came into existence. Beginning with Guru Nanak Dev, the first Sikh Guru, the author reflects upon the life of all the Gurus and thereby maps the trajectory of Sikhism towards a more crystallized identity- culminating in the formation of the Khalsa Panth by Guru Gobind Singh. The author then talks about how, post-Guru Gobind Singh, Banda Bairagi took over the Panth and wreaked havoc on the Mughals.

Following this, the author writes about how the Sikhs survived in the face of Ahmad Shah Abdali’s brutal onslaught. This period also coincides with the coming up of different Misls across Punjab. In the concluding section, the author documents the golden epoch of Sikh History, i.e. the formation of the Sikh empire under the able leadership of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. The book ends with the death of the Maharaja.

The book for the most part has a seamless flow, especially the first five chapters where the author covers in exhaustive detail, the life of the 10 Gurus. The parts which I personally enjoyed reading the most were Appendix 1 where the author critically analyzes the Bala Janamsakhi (hagiography of Guru Nanak Dev) and Appendix 4 where he discusses different perpectives regarding the authorship of Dasam Granth. The book unfortunately is loaded with a secular liberal narrative. At numerous instances, narrative takes precedence over scholarship. It is this narrative which I will examine in this review.

Is Sikhism Born Out Of A Wedlock Between Hinduism And Islam?

Sikhism and Hinduism, barring the outside markers of identity, are fundamentally quite similar, be it their philosophy or their practices. Whereas the similarities between Sikhism and Islam are very superficial. It came as a surprise to me when Khushwant Singh claimed that Sikhism was born ‘out of a wedlock between Hinduism and Islam.’ To the contrary, W.H Mcleod, in his paper, “The Influence of Islam upon the thought of Guru Nanak”, shows that the core teachings of Guru Nanak were inspired by the contemporary ‘Sant’ terminology. He writes,

“Characteristic Sufi terms such as dhikr, khauf, tawakkul, yaqin, muraqaba, irada, ma’rifat, talib, and tauba are either rare or totally absent. Even when such words make an occasional appearance they are not generally used in a sense implying the precise meaning which they would possess in Sufi usage, and in some cases they are introduced with the patent intention of providing a reinterpretation of their meaning…in some fundamental respect, Guru Nanak’s thought is in direct conflict with that of Sufis. The obvious example of this is his acceptance of the doctrines of Karma and transmigration. We should also observe his denial of the need for esoteric perception, the contrast between the human preceptors of the Sufi orders (sheikh, pir or murshid) and Guru Nanak’s understanding of an inner voice of God (the guru), and differing roles ascribed to divine grace.”

Khushwant Singh then writes,

‘Muslim conquerors had tried to destroy non-believers and their places of worship, the Sufis welcomed them into their homes and embraced them as their brothers…The Sufis did not need to do very much more to win over large number of converts.’

The narrative of Sufis being all-embracing angels had a good run then, but today it has run out of steam. Sanjay Dixit, in his book ‘Unbreaking India’, writes that how early Sufism “emphasized ‘immanence of divine’ alternated between complete fusion with the divine and reflection of the divine within the human soul—something akin to Advaita and Dvaita of Hinduism.” However, this was quite short-lived, and by the 11th century, with the coming of Al-Ghazali, this spiritual side of Sufism ceased to exist. By the time Sufis entered India, they were as fanatic as the Muslim conquerors if not more. As Sanjay Dixit writes,

‘The Chishtis accompanied the invading Army of Mohammad of Ghur and set base in India. The line of Moinuddin Chishti– Nizamuddin Auliya and Bābā Farid is the Chishtiyya Tariqa, that later got sub divided into many silsilas along Nizami and Sābri divisions. Suhrawardys had come to Sindh even earlier. Next was the turn of Kashmir where Sayyid Mir Shah Hamadani (Shah Hamadan), a Kubrawi, wrought such untold misery for the Kafirs that it resulted in the Code of Umar 77 being applied there, and was instrumental in forced conversions and the First Exodus of Kashmir.’

Khushwant Singh in this book has made a lot of remarks on Hinduism but the one on Adi Shankaracharya stands out where he describes him to be a monotheist. He writes, ‘Shankra exhorted to return to the Vedas for inspiration. His Hinduism was an uncompromising monotheism and a rejection of idol worship.’ To me, it seems like, Khushwant Singh, though being a prolific writer, juggled in many genres, so maybe he confused Adi Shankracharya with Dayanand Saraswati. These kinds of absurd remarks by Khushwant Singh directly call into question, his understanding of Hinduism and Islam.

Guru Nanak Dev And His Life

One of the most well-known events in the life of Guru Nanak Dev is when he went to take a bath in a stream, appeared after three days, and proclaimed, “There is no Hindu, there is no Mussalman.” Khushwant Singh, in his book, uses this proclamation to establish that Guru Nanak was interested in going beyond Hinduism and Islam, and was keen to begin something new.

Rather than taking the above statement in the literal sense, one must examine the philosophical underpinnings of the same as similar notions of thinking beyond worldly social divisions or identities, such as that of Hindu-Muslim, have time and again been preached by many Hindu saints. Dr. Koenraad Elst, in his book, ‘Who is a Hindu’ writes,

“Ethics and metaphysics are serious subjects; three days is a short time if you want to free yourself from your acquired notions of ethics and metaphysics, and start a whole new religion. Infact, for all we know, Guru Nanak continued the practices of the Bhakti saints that had come before him, starting with the mental or oral repetition of the Divine Name, Rama nama…‘There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim’ (for that is the literal translation, and it makes a difference) does not mean ‘I, Nanak, am neither Hindu nor Muslim’, it means a wholesale rejection of the Hindu and Muslim identities valid for all self-described Hindus and Muslims as well. It means that the Self (Atman, the timeless indweller, the object-subject of his ‘mystical experience’) is beyond worldly divisions like those between different religions and sects. The Self is neither black nor white, neither big nor small, neither Hindu nor Muslim, neither this nor that; neti neti, in the Upanishadic phrase. This insight is as typically Hindu as you can get.!”

Another interesting instance mentioned in the book is that of Guru Nanak Dev’s death. His death is described by the author as, “ “Said the Mussalmans: we will bury him”; the Hindus: “we will cremate him”; Nanak said: You place flowers on either side, Hindus on my right, Muslims on my left. Those whose flowers remain fresh tomorrow will have their way.”…Next morning when they raised the sheet they found nothing .” This story, in all probability, is a legend inspired by a similar story regarding Kabir as recorded in “The Bijak of Kabir” by Ahmad Shah.

There are many such instances mentioned in the book which seem to be inspired by some earlier story, an example being the story of his journey to Multan. It is said that the holy men of Multan sent a cup of milk filled up to the brim to Guru Nanak Dev indicating that the city had all the holy men it needed. Guru Nanak Dev kept a jasmine petal on the milk and returned it, meaning that there was still some space for more. This legend is related to Abd al-Qadir Jilani (1077-1166 AD), as mentioned in “Sufism: Its Saints and Shrines” by J.A Subhan.

The other stories of Nanak’s visit to Mecca and Baghdad are also given a place in the book. The visit to Mecca is mentioned in many Janamsakhis but with varying details. This claim of visit to Mecca and Baghdad (at that time an important place for Muslims) by a non-Muslim seems quite far-fetched to be true. W.H Mcleod in his book, “Guru Nanak and Sikh religion” writes,

“Adventurers such as Burton and Keane have proved the possibility of non-Muslims entering Mecca, but they have also shown the success in such an attempt could be attained only by means of a thorough disguise, both in outward appearance and behavior. Guru Nanak would doubtless have been sufficiently conservant with Muslim belief and practice to sustain his disguise, but it would have been a violation both of his manifest honesty and of his customary practice of plain speaking.”

In the same book, Mcleod has critically analyzed all the sources which talk about Nanak’s visit to Baghdad and has found the story to be false. Thus, given that many of these legends about Guru Nanak’s life have almost similar antecedents, it won’t be incorrect to say that such claims made in the book cannot be taken as true facts to build upon.

How Rapidly Did Sikhism Grow?

The author writes “…the names of other saints of the time passed into the pages of history books while that of Nanak was kept alive by a following which increased day by day.” This is such an absurd claim to make. Medieval period saints which came around the time of Nanak like Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, Ramanand, Vallabha Swami, Tukaram, and many others have their traditions running very successfully.

The other claim that Nanak had his followers increasing day by day is also not backed by any source (a repeated mistake by Khushwant Singh throughout the book) and needs to be thoroughly examined. J.D Cunningham in his book, ‘History of the Sikhs’ notes that, “Ram Das is among the most revered of the Gurus… His own ministry did not extend beyond seven years, and the slow progress of the faith of Nanak seems apparent from the statement that at the end of forty-two years his successor had not more than double that number of disciples or instructed followers.” And thus, this claim of Nanak’s ever-growing followership too needs to be verified.

Did Mian Mir Lay The Foundation Of Harmandir Sahib?

The story of Mian Mir laying the foundation of Harimandir Sahib is widley accepted in the mainstream, and hence, also finds mention in the book. But again, the author does not provide any source to back this claim. Also, no contemporary Persian source, and interestingly, not even the biographers of Mian Mir mention it. The first mention of Mian Mir laying the foundation stone comes three centuries after the foundation of Harimandir Sahib in the third edition of Giani Gian Singh’s, “Panth Prakash”. Here too no source is given for this information.

Was Banda Bairagi a Sikh ?

The first Sikh state was built by the charismatic Hindu Banda Bairagi. In the book, he is shown to have become a follower of Guru Gobind Singh and remained one till his death. But there is more to his story. The verses 18,19,20 and 21 of Sri Gur Panth Prakash show how Banda Bahadur no longer was a follower of Guru but of Bairagi Vaishnav sect. This claim is further supported by the fact that Banda used to baptize people not by amrit pahul (initiation ceremony started by Guru Gobind Singh) but by the ceremony of charan pahul. Charan Pahul was usually the initiation ceremony used by Hindu sects of that time.

Misleading Scholarship

For a book that covers such a vast span of history, one not only expects academic rigor but also intellectual honesty on part of the author. In this book, in many instances, the scholarship of Khushwant Singh is misleading, to say the least. As for example, Khushwat Singh writes that it was a Hindu Banker Chandu Shah who betrayed Guru Arjun Dev which led to him being tortured to death. In the reference section, he writes, “There is nothing contemporary on record to indicate that the Hindu banker, Chandu Shah, was in any way personally vindictive towards the captive Guru.” Further, he presents Macauliffe’s ‘The Sikh Religion’ as a reference but Macauliffe too does not provide any source for this claim.

Later in the book Khushwant Singh narrates the famous story of how Guru Teg Bahadur sacrificed his life to help a delegation of Kashmiri Brahmins who were forced to accept conversion to Islam. He cites Macauliffe’s ‘The Sikh Religion’ as a reference but Macauliffe again does not provide any source for this claim. Koenraad Elst has done a critical analysis of this claim in his book ‘Who is a Hindu’. He writes,

“In most indo-Aryan languages, the oft-used honorific mode of the singular is expressed by the same pronoun as the plural (e.g. Hindi unka, ‘his’ or ‘their’, as opposed to the non-honorific singular uska), and vice-versa; by contrast, the singular form only indicates a singular subject. The phrase commonly translated as ‘the Lord preserved their tilak and sacred thread’ (tilak-janju rakha Prabh ta-ka), referring to unnamed outsiders assumed to be the Kashmiri Pandits, literally means that He ‘preserved is tilak and sacred thread’, meaning Tegh Bahadur’s; it is already unusual poetic liberty to render ‘their tilak and sacred thread’ this way, and even if that were intended, there is still no mention of the Kashmiri Pandits in the story. This is confirmed by one of the following lines in Govind’s poem about his father’s martyrdom: ‘He suffered martyrdom for the sake of his faith.’ In any case, the story of forced mass conversions in Kashmir by the Moghul emperor Aurangzeb is not supported by the detailed record of his reign by Muslim chronicles who narrate many accounts of his bigotry.”

Later in the book, Khushwant Singh writes that it was a Brahmin servant who had betrayed Guru Gobind Singh’s two sons Zorawar Singh and Fateh Singh, and led them to get executed on the orders of Wazir Khan. In the reference section he writes, “According to Sikh chronicles, the boys were betrayed by their Brahmin servant and executed by the order of Wazir Khan.” It would have been easier for the reader if he would have mentioned which Sikh chronicle he was referring to. Many prominent Sikh sources for history like Ratan Singh Bhangu’s “Panth Prakash”, Sainapati’s “Sri Gursobha”, and Kahn Singh Nabha’s “Gurshabad Ratnakar Mahankosh” also mention the Brahmin story, but none gives any primary evidence to support this claim. And hence it can be said that at best the story of a Brahmin betraying Guru’s son is a mere oral legend and should not be seen as a historical fact.

There are many other instances where Brahmins played a cardinal role in Sikh history but those instances surprisingly are not highlighted in the book. The prime examples being Mati Das, Sati Das, and Dayal Das who sacrificed their lives along with Guru Teg Bahadur. Swami Ramanand, and Surdas ji, whose compositions get a place in the Guru Granth Sahib were Brahmins.

While the book ‘A History of the Sikhs’ by Khushwant Singh is a valuable resource to know about Sikh History but it suffers the same drawbacks that the mainstream secular-liberal scholarship does. Khushwant Singh, at times, seems to be serving his bias much more than the objective truth. This becomes even more problematic when this book is read by a large number of people to know about Sikh History. Almost any book on Sikhism which is popular among mainstream audiences uses Khushwant Singh’s books as reference. Unfortunately, this helps popularize untrue facts which ultimately leads to strengthening of propogandist narratives driven by vested interests.

Leave a Reply