Madhu Kishwar's book is a well researched, meticulously compiled and honest account of the dynamics and evolution of the complex relationship between the current PM of India and the largest minority community of the country and how the media has tried to shape it for the worse.

Modi, Muslims and Media

It was already late in the day when my attention was drawn to Madhu Kishwar’s book: Modi, Muslims and Media. Voices from Narendra Modi’s Gujarat, published in 2014 by Manushi Publications, Delhi. Yet it explains a lot about the hate-Modi campaign after the 2002 riots and about Modi’s style of governance in Gujarat, prefiguring his term in power at the centre.

Progressive

In the old days, Madhu Kishwar used to be classified as a progressive and “therefore” a Leftist. This was already assumed from her appointment as professor in the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies. It became a worldwide certainty with her pioneering work as founding editor of Manushi(more or less “she-human”), a magazine devoted to a variety of issues pertinent to women’s rights. That reputation has opened many doors for her and facilitated her international recognition as the voice of Indian women, the “mother of Indian feminism”.

Yet, she was by no means a puppet in the hands of the American trendsetters of contemporary feminism. They already would have frowned if they had known that she refuses to espouse “feminism” – a crude, divisive Western term implying a confrontational stance, not rooted in Hindu civilization with its stronger awareness of the whole. According to the author’s biodata on the backpage of this book, her struggle is devoted to “democratic reforms that promote greater social justice and strengthen human rights of all, especially women”. She is also known to “avoid the trap of ‘isms’ and prefers to anchor her politics in truth, compassion and non-violence”.

During the Ayodhya agitation, I had assumed she was just one among the Indian Leftists when I read her article about a murder of one of the Ayodhya priests by a rival Hindu faction, the kind of incident that those out to blacken the VHP would be sure to highlight. So, back then, I assumed she was just another Hindu-bashing secularist: not because she reported a crime, probably truthfully, but because she did not give much attention to Ayodhya except to report such a crime.

Yet, that progressive reputation came in doubt with the publication of this book. Insiders already knew that her position was subtler than the usual one-dimensional secularism. And why would a successful researcher ask the CSDS for leave to go interview villagers and riot survivors in Gujarat, that hell-hole ruled by Satan himself, Narendra Modi? With this book, issued during Modi’s bid to be elected as Prime Minister, the truth became widely known: Madhu Kishwar has been Modified.

Modi’s record

India is otherwise quite comfortable about supping with the devil. Regarding terror in the name of Kashmiri separatism or Maoism, you are perfectly at liberty to whitewash it. “But”, and this is her justification for having started on this book project, “to say a word in appreciation of governance reforms in Gujarat, or to credit Modi for having given Gujarat its first ever riot-free 12 years since independence, is to commit political hara-kiri – one is forever tainted with the colours of fascism. This intellectual terror created by the anti-Modi brigade pushed me to find out for myself the reason behind this obsessive anxiety about Modi.” (p.13)

In 2002, she went along with the media version and assumed Modi’s guilt for the riots, which killed over a thousands persons, three-quarters of them Muslims. She signed anti-Modi statements and Manushi too published the usual indictments of the Modi government. But as the actual event of the riots (March 2002) receded into the past, the obsession with Modi only went on increasing. One culprit after another got convicted and sent to prison. Modi, by contrast, kept on surviving the investigations and trials against him. He even challenged his adversaries: if they could prove any complicity whatsoever against him, he should not just step down, he should be hanged. But as of now, his neck is still intact.

Narendra Modi was Chief Minister from 2001 to 2014, and won the elections very convincingly three successive times. The Gujarat that Madhu Kishwar got to see, already had a decade of Modi experience, and seemed to like what it got.

Shortly after assuming power, he was challenged on 28 February 2002 by the arson of a train wagon full of Hindu pilgrims returning from Ayodhya. The fire was lit by someone from a mob of Muslims awaiting the train in Godhra railway station. The next day, this led to Hindu retaliation on a large scale. As often in communal riots, the police only added fuel to the fire with its partisan and provocative interventions.

Modi sent for veteran police officer KPS Gill and told him: “My first principle as a devout Hindu and as a politician is Sarve Janah Sukhino Bhavantu (may all the people in the world be happy and peaceful). I will be thankful to you all my life if you can help me end this mayhem at the earliest.” (p.260) Gill accepted and, like Jagmohan before him in Kashmir, made himself personally accessible to all officers with important data, complaints or suggestions. He talked with the officers, and those he considered unreliable were immediately transferred to less sensitive areas: “Within three months, KPS Gill had succeeded in his mission to tighten the law and order machinery. Since then Modi has kept a tight leash on the issue. (…) Modi did not allow any retaliatory violence when Ahmedabad and Surat were targeted with serial bomb blasts by jehadis, killing 56 and injuring 200 people.” (p.262)

Many of her stories about Muslims dissenting from the approved secularist version, can readily be proven by related data, e.g.: “KPS Gill’s popularity with the Muslim community can be gauged from the fact that long after completing his task, he received numerous invitations to inaugurate reconstructed colonies meant for Muslims and attend weddings in Muslim families.” (p.261)

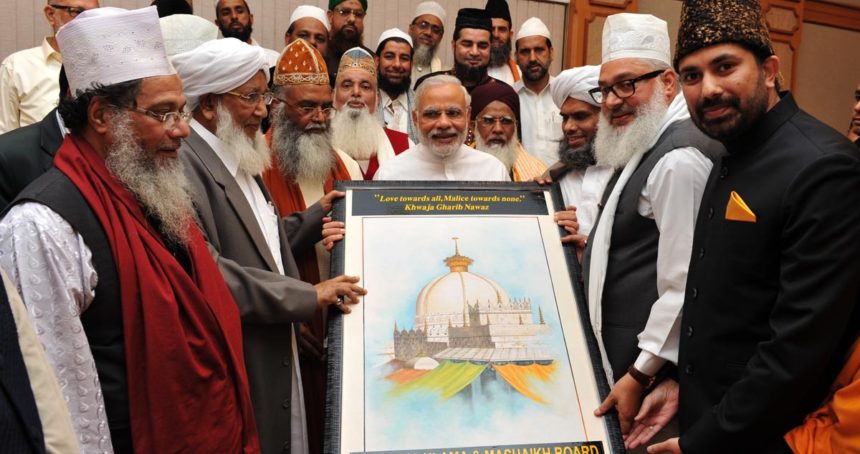

Muslim acclamation

Madhu Kishwar relates at length how the communally sensitive state of Gujarat, for decades up in arms in religious strife, has settled down in communal amity. Unlike in the past, the communities frequent each other’s neighbourhoods. Muslim women relate (and this is the kind of information only a woman could extract from other women) that, once the communal suspicions had been lifted, they felt more at ease in Hindu than in Muslim neighbourhoods.

Nowadays, Muslims even vote for Modi, who “not only established good rapport with Muslim voters (…), but actually got solid support from almost every section of the Muslim community for his very first election”. (p.175) He received even more support after than before the riots. To explain this inconvenient truth away, Modi-bashers allege that Muslims are “intimidated” into voting this way. I wonder if they ever have been seriously scared themselves. On the street you might be intimidated by bullies, but in the secrecy of the voting booth, you can perfectly take your sweet revenge. If they had been intimidated out there, they would have had all the more reason to make a fist against the party of the bullies in the voting booth. But no, it turns out they freely, under no pressure, voted for Modi, clearly charmed by his pro-harmony policies,

Yet, among activist Muslims, as among Nehruvian secularists, the hatred of Modi was enormous: “Maulana Vastanvi was forced to resign as vice chancellor of Deoband University simply because he shared the thought that Gujarati Muslims had benefited from the inclusive development policies of Modi’s government. Shahid Siddiqui, the editor of the Urdu daily, Nai Duniya, faced severe attack and abuse” and was “expelled from the Samajwadi Party” for “simply doing an interview with Modi in which Modi defends himself against various charges”, even though the questioning was “in no way soft”. (p.16) But this was only the Muslim variety of a more general trend in the media.

Media

In his introduction to this book, Salim Khan observes: “In recent times, media trials have become more important than trials in the courts.” (p.9) This book “reveals how a systematic misinformation campaign took form and shape to project a totally misleading picture of the 2002 riots and the status of Muslims in India.” (p.10-11)

Fortunately, we now have the internet. It breaks through the monopoly on information and opinion-building that the Hindu-bashers used to have. An important source for Madhu Kishwar was the website gujaratriots.com, acknowledged as the work of an anonymous student. His identity can by now be revealed: MD Deshpande, who has now turned his list of data into a book, The Gujarat Riots, Another survey of the riots is the paper by Nicole Elfi: Godhra: the True Story. Now that the truth becomes more widely known, one new secularist account tries to beat life into a dying horse of the Gujarat atrocity narrative: Rana Ayyub’s The Gujarat Files. Anatomy of a Cover-Up. An important part of Elfi’s and Deshpande’s sources has been the media themselves, whose reporting in tempore non suspecto is often at odds with the later instrumentalization of earlier incidents in a grand Modi-bashing narrative.

From this large and crucial part of the book, I will quote only two incidents. One is where Modi was questioned about an incident where a former MP, Congressman Ehsan Jafri, fired his gun into an admittedly violent mob, which infuriated it to the point of setting his house on fire. What did Modi say?

“Here is an illustrative example how every word that Modi uttered following the Godhra incident was twisted and distorted by the well-oiled misinformation machinery set up by the Congress and the Left.” (p.287) Experienced liars know how to lie without actually lying. Thus, you can quote selectively, where every word quoted has actually been said, yet convey a very wrong impression of this statement’s thrust by leaving out part of it. So, Modi explained that this violence was a causal chain of action and reaction: “Kriya pratikriya ki chain chal rahi hai.” By itself, this seemed to say that the arson was understandable as being only the reaction against the shooting – and thus kind of justified. What the media carefully left out, was the next sentence: “Ham chahte hain ki na kriya ho aur na pratikriya”, “I want neither action nor reaction.” (p.287) In Teesta Stetalwad’s propaganda organ, this story has kept on resurfacing, and thence in all media that rely on her.

Arundhati Roy, Booker Prize winner and a big name among Western and Westernized audiences, was expected to prioduce some titillating atrocity literature about how unspeakably evil Hinduism is; and she did. She made the story more colourful by claiming that Ehsan Jafri’s two daughters had also been raped and killed. However, their brother issued a clarification that his sisters had not been in town at the time, one even being in the US. Being so diametrically contradicted after such a high-profile claim would have shamed a lesser mortal, and certainly been reprimanded and disowned by the editor formally responsible for a statement that turned out to be slanderous in the extreme. But not her, for she retained the backing of Outlook editor Vinod Mehta and dared to snap back: “Unfazed, Roy replied that she had got her info from two other sources, one a report in Timemagazine and another, a supposedly independent fact-finding mission.” (p.286)

Far from being a non-partisan and reliable source, this “fact-finding mission” had been carried out by the avowed anti-Modi crusaders Teesta Setalwad and Shabnam Hashmi. As for Time conveying the same mendacious atrocity claim, it illustrates a phenomenon I have highlighted at some length in my Ph.D. dissertation Decolonizing the Hindu Mind (turned into a book): the “circular argument of authority”. When Indian secularists try to trump their opponents’ arguments, they readily invoke Western sources as their authority. How can you dare to claim that Time would be wrong? Only, the source of those prestigious Western media are the secularists themselves. Western press correspondents in Delhi hobnob a lot with Anglicized Indians, especially secularists, whom they socialize with at lectures or on the cocktail circuit. Their view of India is totally shaped by their Indian contacts, apparently with slanderous rumours included.

The same acclaimed fiction writer related how a pregnant woman had her stomach ripped open by the Hindu rioters. Tehelka, Harsh Mander in Times of India, even the BBC ran with it: “But nothing beats the mischief and arrogance of Arundhati Roy’s blood and gore reporting on the same story on the basis of hearsay.” In Roy’s version, after the woman died, “someone carved OM on her forehead”. What a gruesome illustration of Hindu inhumanity, almost too good to be true. And indeed, BJP MP Balbir Punj contacted the police, who had no such case booked. They contacted Roy, who, through her lawyer, refused to cooperate. (p.285-286)

Overcoming the Modi scare

It is doubtful that recent world history has seen another campaign of slander on that global scale. In 2005, the USA banned Modi from entering the country. US-based Indian Muslims and secularists set up a Coalition Against Genocide, no less. The charitable Indian Development and Relief Fund was blackened and largely put out of business by a hate campaign because of its alleged ties with Modi. Worldwide, the ludicrous story caught on that in Modi’s Gujarat, the history textbooks glorify Adolf Hitler. As late as the spring of 2014, The Economist counseled editorially against the choice of Modi as Prime Minister, still citing the 2002 events.

Meanwhile, Narendra Modi himself came shiningly cleared out of his investigations and trials. As MJ Akbar observed: few if any politicians are put through such a long-lasting and extreme test, and if Modi came through, it simply means he is innocent. Akbar left as spokesman of Congress and started working for the BJP, well before it came to power. He was but one among many insiders in Indian politics who lost his illusions about Congress.

During the Ayodhya agitation ca. 1990, I saw little difference between the BJP and Congress. Congressmen Gulzarilal Nanda (interim-PM after Lal Bahadur Shastri’s death) and Dau Dayal Khanna actually started the Ayodhya “liberation” movement, and PM Rajiv Gandhi was even considered for laying the temple’s first stone. At that time, even if their atitude towards Hindu issues was cynical and opportunistic, they did care about their Hindu votebank. Brahmins had supplied the manpower (and certainly the martyrs) for Congress during the Freedom Movement, and the Congress leadership was still largely Brahmin. Unlike the BJS-BJP, who talked a lot about Hinduness, those traditionalist Congressmen took their Hinduness for granted; it came naturally to them. But the last Congressman in this vein was Narasimha Rao, the best PM India ever had (don’t judge Modi until his term is over), and significantly, he was hounded and humiliated by his party at the end of his life and especially on the occasion of his death. Congress could stoop so low because it had become a different party, and today it is an instrument of the forces out to break India.

And so, Congress has also shown its worst side during the Gujarat crisis. It stands to reason that Madhu Kishwar came away with a low opinion of Congress: the normal rivalry between political parties was simply no warrant for the intensely hateful campaign against Modi. But it is not as if Congressmen and BJP men are two different species. Rather, the parties are communicating vessels, and many BJP politicians who had accounts to settle with Modi crossed the floor: BJP leaders “Keshubhai Patel, Praveen Togadia, Babu Bajrangi, Gordhan Zadaphia, and the late Haren Pandya openly helped the Congress in launching a smear campaign against Modi. All of them brazenly joined the Congress during elections in order to topple Modi’s government.” (p.263)

Madhu Kishwar describes several conflicts between the Modi state government and members of the Sangh Parivar, with her sympathies visibly on the Modi side. Some Hindu-minded hot-blooded factions considered Modi too pro-Muslim, a surprise only if you had believed the secularist propaganda against him. On the other hand the BJP establishment had largely borrowed and believed the secularist propaganda about him. Therefore, it briefly considered his dismissal as CM, and palpably didn’t like the enthusiasm among their workers and the Hindu electorate at the prospect of Modi becoming the party’s PM candidate. Till the last moment, they were more comfortable with the alternative of Rajnath Singh. The BJP itself had interiorized its enemies’ cultivated Modi scare; it was set straight by the voter.

The aftermath

But now, here we are, and Narendra Modi is the Prime Minister. Is Madhu Kishwar happy about that? The book can’t tell you that anymore, but we can get an idea from her interventions on an internet list we share. So yes, she is relatively happy in the sense that Congress or the Communists would have been worse. On the international scene, Modi is simply a revelation. On the much-touted “development” front, he is said to be doing rather well. But the big disappointment is on the cultural front. The Hindu agenda for which the BJP was once known, has not determined actual policies at all.

Thus, the Congress-cum-Communists gave India the Right to Education Act, very costly for schools “except minorities institutions”. The consequence is that hundreds of Hindu schools have had to close down. Why is the BJP not doing anything about this? Because it wants to be seen as secularly goody-goody rather than as taking up Hindu causes. Yet, closure of schools definitely harms the BJP’s priority of “development”, and dismantling this mechanism of communal (viz. anti-Hindu) discrimination is not some Hindutva fringe agenda but a secular concern par excellence.

Modi has been carried to power by ordinary Hindus (and, as this book argues, by some Muslims too) who volunteered their time and energy, and in some cases, their fame. Madhu Kishwar was one of them. After the election, they were dropped like a hot potato, and their suggestions or petitions fell on deaf ears. Yet during the campaign, this spontaneous enthusiasm was quite a sight. It was a felicitous coming together of cultural conservatives with free-market economic reformers. Today, this latter, development-minded wing is being well served. It could of course always be more and better, but already there is just no comparison with the preceding Congress government. By contrast, on the cultural front, nothing much has changed.

In this book, Madhu Kishwar has sketched not just the people’s reaction to Modi, but also her own interaction with him. She interviewed him a number of times, and describes his asceticism and discipline (vintage RSS), his workaholism and dedication, and his heartfelt attention to other people and their concerns. What seems to be missing, is an awareness of the culture war that is raging: several aggressors against one non-defendent, Hinduism.

She describes how Modi refused to react in kind against the vicious slander spread by the likes of Teesta Setalwad and Arundhati Roy, and how he honestly wondered aloud why they were doing this, as he had never done them any harm. That neatly sums up the problem: most Hindus are not even aware that there are enemies out there who hate them and want their downfall. A Dutch proverb says: “As the inn-keeper’s nature is, that way he trusts his guests.” Hindus are harmless against other communities, they don’t think in terms of communal conflict, and so they don’t notice the designs others have against them. I saw Modi myself, in Brussels just a few days after the bomb attacks there by Muslim terrorists (22 March 2016). Trying to be nice, he pleaded that these attacks cannot posssibly be motivated by religion, projecting his certainty about Hinduism’s harmlessness onto Islam.

The aggressors don’t need you to have injured or even offended them. If at all needed, they will readily invent a casus belli, but at any rate, they are on the attack. And what better opportunity than to put a popular Hindu leader in the dock for the Gujarat riots, nothing less than “genocide”? Fortunately, we have had Nicole Elfi and MD Deshpande to set the record straight, and now Madhu Kishwar to draw up a balanced and well-documented picture of how Modi’s record as Gujarat CM really was.

Madhu Purnima Kishwar: Modi, Muslims and Media. Voices from Narendra Modi’s Gujarat, Manushi Publications, Delhi 2014.

Leave a Reply