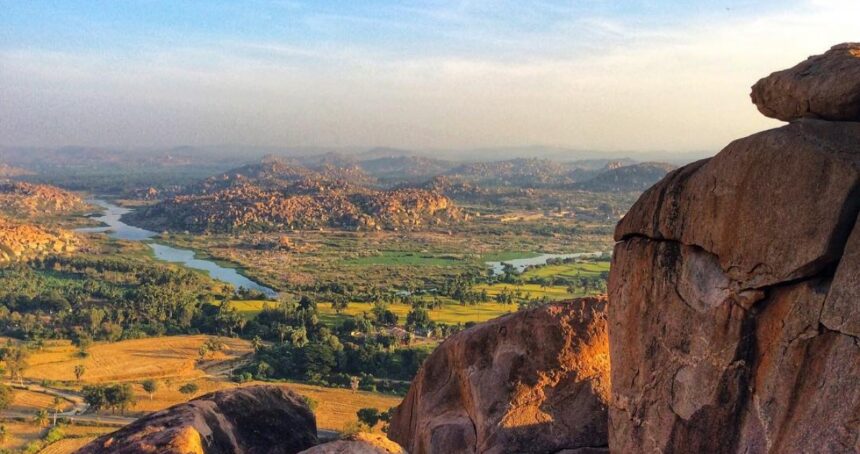

Kishkindha, as the kingdom of the Vanara King Sugriva evokes feelings that transport you to another time.

9 Days – A magical journey of unexpected revelations!

Love is not a worldly phenomenon. Love is not mortal. Love is a whirlwind that works beyond our knowledge.

If you have read Juluri’s work before, then he sings in a slightly different tune in his latest book. As thought-provoking as any of his other works, Nine Days in Kishkinda is a very personal journey, even though the readers can relate to it at many places. This slim, personal and profound book raises many questions, answers some and leaves us to ask some of our own, about life, living, service and faith.

A travelogue, filled with magical happenings, that combines stories of families serving in small towns for generations, of visiting ancestral homes, and of letters and voices emerging from the depths that we did not know existed, revitalizing memories and faiths.

There is a common thread throughout the book—that deals with memory, preserved in words, chiseled in stone and tied to family homes, creating bonds beyond time, weaving a link of continuity from one generation to the other.

As the book gives snippets of a field trip to Hampi that Juluri arranged for his class combined with a family visit, it intertwines memories and mementos as a starting point for a larger conversation on the place of people, tradition and faith in our lives. A sense of ancient history is evoked as the author sees his young son engage in rituals that are millennia old.

Another thread working in tandem with memory is the concept of the ‘sacred’, which is apparent even in the opening sentence.

‘My father’s breath was holy.’

The contemplation on the sacred, considering ‘something holy’ has been under attack for decades by scholars who want to extract meanings of their own making from sacred Indian texts, is the need of the hour. As I read the book on Kindle, the irony of technology automatically translating Hanuman as ‘a kind of an animal’ was not lost on me. Is it really the technology that will save us? Or is it the consciousness that created technology that vows to use it for the betterment of mankind that will be our saviour? In the end, it is human intelligence that will decide our fate. And that human intelligence, as revealed in Juluri’s travels, is nurtured among family interactions, in relationships and in search for our identity, through living rituals, through old temples and even through letters and words left by parents.

Juluri writes:

‘Random, modern-mind questions, obsessed about the creation of the creator, rather than the obligation of figuring out our time and place in our own createdness, in the first place’

Reading the book, at times I was transported to those places in India that are rich with history and still mired in obscurity where nameless people continue to serve and be grateful that they are privy to a dialogue with history that, in some way, the modern mind has forgotten. These people are not worldly, nor do they speak the language of Starbucks, but have wisdom far, far deeper, that knows that continuation of any knowledge, lineage, family, and love needs effort and understanding, and most of all, time. It takes more than a few generations to thoroughly know a place before one can serve it.

Where today ubiquitous words combined with luring images beckon us to consume more, Juluri’s book makes us reflect on how memories might be left behind through words, through stories, through hand-written letters, through works of art and rituals performed generation after generation. Several passages beautifully weave themes of environmentalism with what is held sacred, both tangible and intangible.

We live to please our gods; sometimes, we do so with ritual forms of worship, with milk and coconut water and honey (which by the way skeptics, we don’t necessarily waste, but consume afterwards), and sometimes we do so simply by adhering to our dharma, by practicing kindness, fairness and selflessness with others. We please our gods by pleasing our children. We please our gods by pleasing our elders. We please our gods by pleasing our own selves in appropriate and I think ecologically sustainable manners.

Dharma is love as it is always.

The slimness of the book defies the deep and lasting message that the book contains. I personally think the book should be read in one go, and then mulled over the next few days. The book is available as an ebook and provides much more food and nutrition for the mind for the small amount it charges.

Leave a Reply