Sanskrit with its abundant literature draws you continuously and ignites such passion in your heart that it is tough to let go.

Why I'm learning Sanskrit?

“I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to study Mathematicks and Philosophy. My sons ought to study Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History and Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture, in order to give their Children a right to study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine.”

John Adams

A crossover from Mechanical engineer to classical Sanskrit studies is a difficult decision to defend. In general, things do not happen in real life as they do in movies. That palpable difference is, after all, one of the reasons why we love cinema. Our lives do not finish in a neat narrative moment that resolves as it fades to black. We do not, in general, experience our lives as a grand unfolding of plot points that crescendo-culminate in a grandiose happening. Rarely do we have that succinct pointed epiphany.

Yet, in retrospect, I see Ananda Coomaraswamy’s works as the trigger to the changes that followed. In one essay on the state of (British-imposed) Education in India, in particular, he’d written,

“The most crushing indictment of this Education is that it destroys all capacity for the appreciation of Indian culture. Speak to the ordinary graduate on the ideals of the Mahabharata–he will hasten to display his knowledge of Shakespeare; talk to him of religious philosophy–you find that he is an atheist of the crude type common in Europe a generation ago…not only has he no religion but he is as lacking in philosophy as the average Englishman…talk to him of Indian art–it is news to him that such a thing exists; ask him to translate a letter written in his own mother tongue–he does not know it. He is indeed a stranger in his own land.”

He is indeed a stranger in his own land— this line is crushing as it is true: On the one hand, we are cut off from our roots and on the other, we will never be able to fully acquire the culture and/or viewpoint of the imperialist. In Coomaraswamy’s words,

“A single generation of English education suffices to break the threads of tradition and to create a nondescript and superficial being deprived of all roots; a sort of intellectual pariah who does not belong to the East or the West, the past or the future.”

Stirred powerfully by these words, I made a decision to learn the language that held the key to my cultural past: Sanskrit.

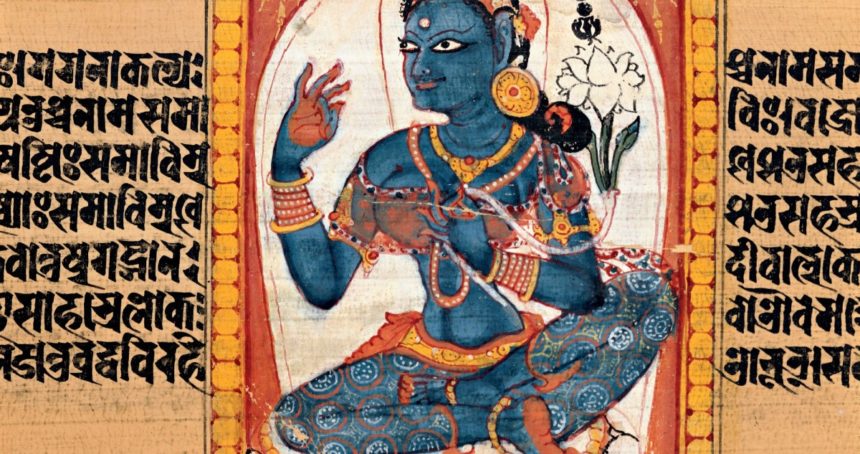

It is four years now, and truly, it has been like stepping off a bus into the clamorous, exotic, slightly menacing streets of a foreign city. What William Jones, the influential British scholar, wrote of Sanskrit “…more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either…”, is perhaps true. Apart from the wealth of philosophical texts, Sanskrit has some of the greatest collection of literature in any language— literature that sing with moral conviction, philosophical boldness, and the joie de vivre of being awake to the world. Sanskrit poetry is truly like miniature paintings: so much color, so much richness, so much depth. Its beauty does not carry you away suddenly, but rather infiltrates you slowly, and you carry it along with you almost unnoticed. Finally, after it has for a long time lain modestly in your heart, it takes complete possession of you, filling your eyes with tears, your heart with longing. My friends and I have learned dozens of Sanskrit poems by heart; we’ve moved, sang, wept, and wrestled with them. We carry them inside us as teachers, healers, and guides. On occasion, I feel I hear it as a chorus pulsating with creation itself.

Now, I want only to transmit the infection: to ignite interest/passion in the heart of students towards Sanskrit.

A serious study of Sanskrit is— without doubt— of immense value. I say this from experience. Studying the classics has allowed me a glimpse into the ideas/ideals of Indian thought— her quest to find the meaning of life, not by turning her back on life, but by learning to see life as it really is— infinite and beautiful, an absolute expression of the Absolute Self.

Studying a non-modern language has taught me the patience to listen to unfamiliar voices, and to continue to listen until they make sense. It has allowed me to realize how the past is/can be a refuge to us— in Edith Hamilton’s words,

“When the world is storm-driven and the bad that happens and the worse that threatens are so urgent as to shut out everything else from view, then we need to know all the strong fortresses of the spirit which men have built through the ages.”

Staying in gurukulas has let me conceive of possibilities of other ways of being in the world that have been lost or that we have falsely come to believe are impossible, thanks to the amnesia enforced by the insistent universalizations of Western modernity. Antonio Gramsci had it right when he wrote,

“Pupils did not learn Latin and Greek in order to speak them, to become waiters, interpreters or commercial letter writers; rather, they studied in order to learn first the discipline of work as such, and second, the possibility of acting in the world in a disinterested, even anti-profit manner.”

Now, I wish only to teach Sanskrit so others can taste the delight of this rhythmic philosophy, this deep, slow breath of thought. From it, we can learn those virtues which, above all others, we need to-day: tranquility, patience, unruffled joy ‘like a lamp in a windless place that does not flicker’.

Leave a Reply