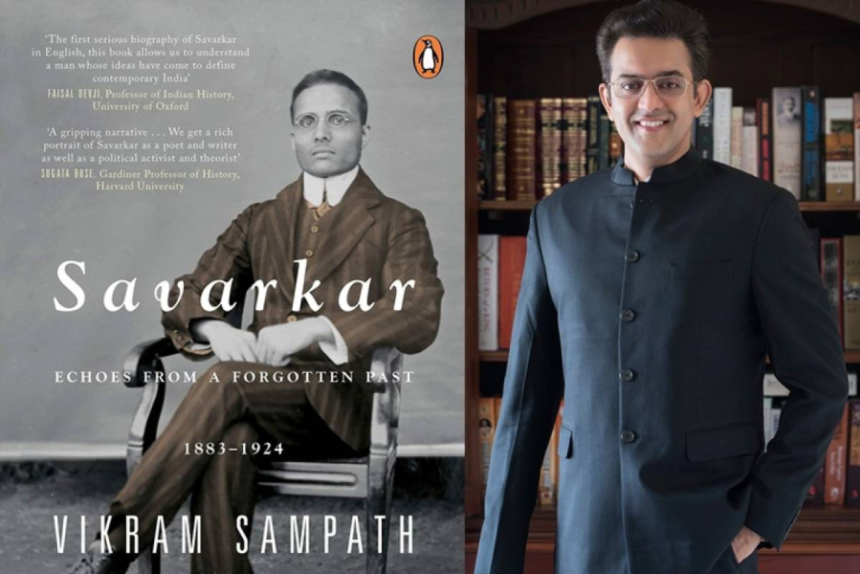

In this review of Dr. Vikram Sampath's book titled: "Savarkar: Echoes from a Forgotten Past, 1883–1924"; Rohan Raghav Sharma analyses and opines on Dr. Sampath's presentation of Savarkar's story, his approach towards Savarkar's sentencing and suffering; interspersed with the correct historical context.

‘Savarkar: Echoes from a Forgotten Past, 1883–1924’ – By Vikram Sampath: A Review

Rating – 4 Stars

This book was a national bestseller and I wanted to see if it lived up to the hype surrounding the release. Apparently, some bookstores refused to even stock it! I don’t recall reading about Savarkar in my ICSE history textbooks and was only vaguely aware of the negative ‘communal’ connotation associated with him.

This book demolishes most of the myths surrounding him while placing his seemingly ‘controversial’ stances firmly in the correct historical context.

1. Gist:

The first half of the biography spans the period 1883 to 1924 and covers Savarkar’s early years and upbringing in Maharastra, his studies at Fergusson College, Poona, and his subsequent stint in London, followed by a series of farcical (and unfair) trials he was subject to and finally, his long drawn out and torturous imprisonment in Andaman.

2. Credit for the Author:

First things first. Vikram Sampath must be commended for this exhaustively researched book with its carefully collated citations and comprehensive references. Sources drawn are as diverse as letters, speeches, imperial government reports, judicial reviews, and newspaper clippings as well. Sources from Savarkar’s native tongue Marathi have also been generously referenced which is a first for an English language biography of the same.

3. Who Was the Man, Really?

Despite its academic nature, Sampath’s prose is easily readable for the layman and paints a compelling picture of Savarkar: a multitalented, highly accomplished man who wore multiple hats with ease. He was an excellent orator, a sensitive poet and intellectual writer, a rationalist, and radical social reformer, and of course an anti-colonial revolutionary at heart. Apart from his keen intelligence, he was equally famed for the sheer magnetism of his persona. His ability to ‘convert’ fellow Indians abroad to the cause of the anti-colonial revolution warrants mention, for it speaks of the sheer strength of his charisma. Some of those he befriended abroad include Madan Lal Dhingra, VVS Aiyar, Madame Bhikaji Cama, and the editor of the Indian Sociologist ‘Shyamji’.

4. Excellent Narration of History:

The book serves a dual purpose. In addition to acting as a biography, we also read of many events of utmost historical importance from a fresh and unbiased perspective. Incidents and events are presented in all their complexity and nuance, unlike the partial narratives we are used to reading in our curriculum and textbooks. These include (but are not limited to):

• Setting up of the Plague Committee amidst the disease and epidemic of 1897

• The Morley Minto Reforms

• Onset of World War 1 (narrated from the Indic perspective )

• The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre and setting up of the Rowlatt Sedition Committee

• The Khilafat movement and the subsequent ‘Round Table Conference’ and calls for Civil Disobedience.

Chapters 9 and 10 detail the historical events so grippingly that I’m tempted to re-read it at some point in the future despite the sordid subject matter.

5. The Indignities and Prison Tortures:

Chapter 8, titled ‘Sazaa-e-Kalapani‘ was a harrowing read. It delves deep into the inhumane tortures that Savarkar was subjected to while imprisoned at Andaman Jail. The treatment meted out to political prisoners during the English Imperialistic era is appalling. Savarkar was lodged in the Andaman jail and was meant to serve two life-imprisonment sentences of 25 years each. The sedition charges against the colonial regime were cleverly trumped up and in retrospect, one can’t help but be struck by the sheer injustice of it all. For obvious reasons, the British authorities took great pains to ensure that those confined to the prison quarters and those in charge were not allowed to communicate all that transpired there.

- Solitary confinement was only scratching the surface of their woes. Being cut off from all social contact and forced to remain indoors indefinitely without a soul to speak to can damage one’s psyche permanently. Prisoners were allowed one rare luxury of recreation – reading, but only occasionally. The sheer scale of social humiliations they were subject to was another horror and it makes one’s blood freeze. It wasn’t mainly the Irish Main warden ‘Barrie’ but also some of the Mohammadian sub-wardens who took sadistic pleasure in torturing and humiliating the Hindu prisoners. The stream of verbal abuses and invectives never ceased. To be shamed as such continually while undergoing life imprisonment? Simply unbearable.

- The British authorities claimed to subscribe to a certain standard of human rights but conveniently suppressed them for those they deemed inimical to their interests. It doesn’t come across more clearly than by assessing the living conditions of the political prisoners. The hard labour they were subject to was a perfect case in point. From making ropes to grinding oil like bullocks tied to a yoke, the details are difficult to digest. This arduous work wasn’t all of it though. Scanty food and clothing only added to the list of their never-ending woes. The quality of food and the conditions under which it was prepared were terrible. The cooks who prepared them took no pains to prevent their sweat and spittle from contaminating the food. The poor prisoners had no choice but to consume it for they had no other means of sustaining themselves. In addition, the lack of lavatories is shocking. The right to answer nature’s calls is a basic human right and even this was denied them, with many often having to pass stools within their confined cells.

- Something worth mentioning is the tactics Chief Warden ‘Barrie’ used to regulate possible acts of defiance and outright dissent. He would create divisions amongst the prisoners to prevent any kind of collective uprising and although he (mostly) failed, it was occasionally effective. Abusing some while exhorting others in each other’s presence was key to sowing the seeds of distrust among them. Reminiscent of the infamous ‘Divide and Rule’ policy that had been indiscriminately utilised by the British to subjugate multiple colonies.

On another note, one must try to understand why some of the prisoners were swayed and turned informers to, or approvers of, the regime they had fought to oust. Very few humans can withstand this kind of inhuman torture for sustained periods without any chance of relief or respite and without something to look forward to. Many prisoners were unused to hard labour, given they came from more educated backgrounds. That and the aforementioned conditions can break a man’s spirit over a period of time. Some feigned sickness and even insanity to escape the despair of this daily grind and gruelling labour. Savarkar himself considered giving up his life on one occasion, although he (thankfully) decided against it. - When in Andaman Jail, Savarkar received news that his law degree had been revoked. All the time, effort, and hard work he’d put into becoming a barrister was gone in a whiff. All future career ambitions were dashed to stone with no signs of relief or respite in the near or distant future. In Savarkar’s case, he was not even granted the dignity of having a record of the work he’d put in. To make it clearer, imagine putting in hours of study and preparation to pass examinations and then having all that simply erased as though it never occurred in the first place! No trace of all your hard-earned qualifications. Words cannot describe the despair and horror that one must feel.

- The Solitary confinement he’d gone through must have been harrowing. Most people went through a much milder version of that during the Covid years. Ceasing all social contact and growing wildly anxious over one’s monetary circumstances can drive you insane, and this man was enduring that under the most pitiable living conditions and squalor unlike most who were confined to far more bearable living quarters or their homes.

This is not an attempt on my part to draw false equivalences of any sort. Modern-day experiences of a millennial during the lockdowns are in no way comparable to that of a political prisoner in the colonial era. Scanty and contaminated food and clothing, unceasing grueling labour, having one’s educational degrees revoked, and having one’s property confiscated can’t be equated with the aftermath of the pandemic. The idea is to compare to differentiate: if most found even this so difficult to bear, the fortitude and resilience required to bear what Savarkar did is unimaginable.

Some may think I’m overemphasising the degree of pain and suffering he’d endured. I only do so since many seem unsympathetic to his plight. Callous naysayers have criticised him for writing pardon petitions to the British after more than 10 years of being imprisoned. One wonders whether they would be able to endure a fraction of what was meted out to Savarkar.

In Conclusion, get this book to gain a factual perspective of a polarising figure in Indian history: one who has been mindlessly maligned to serve petty political interests.

Leave a Reply