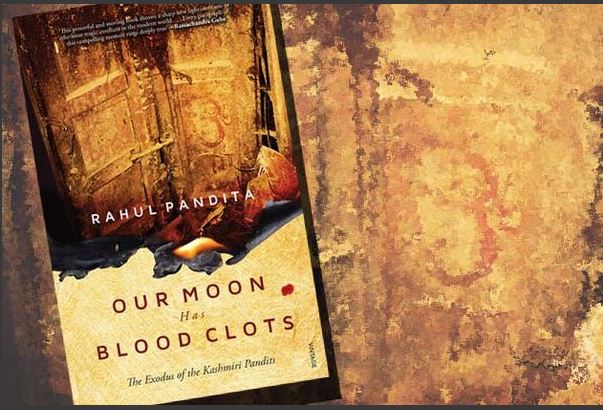

When we think of some of the best books written on the plight of Kashmiri Hindus in Kashmir (especially around the 1990 tragedy), the one book that would certainly make it to the top 3 of the list would be “Our moon has blood clots” by Rahul Pandita. In fact, whenever a non-Kashmiri inquires about the events of 1990 or wants to know the reason why 5 lakh Kashmiri Hindus left Kashmir in a single night, if you are a Kashmiri, chances are you would have recommended them this book; and rightly so. The book does an amazing job of narrating the plight of Kashmiri Hindus during the adverse period of the 90s. So much so that in 2020 renowned producer and director Vidhu Vinod Chopra chose to make a movie based on the book as well, but more on that later.

The reason this book has impacted so many people and carved out a reputation for itself as one of the “must reads” amongst the few other books that highlight the crisis in Kashmir along with the likes of “My Frozen Turbulence in Kashmir” by the then Governor of the state Shri Jagmohan, is most likely because it is able to narrate with such ease the story of a boy who not only witnessed the final days of the millennia-old civilization of his own people but also bore witness to the physical and mental trauma that followed. The book undisputedly does an exceptional job of highlighting the events that lead to the indigenous community of Kashmiri Hindus who had been living in the valley for more than a millennium to leave their ancestral land in one night without giving it a second thought.

One of the reasons this book is so good at certain places is because the incidents it narrates resonate with majority of the victims of the Genocide which makes it a heart-wrenching read for most Kashmiri Hindus. There are instances of some comic relief as well in an otherwise serious book. The author has done a fabulous job at balancing the book’s tone by incorporating various lighthearted moments with his friends and family occasionally. One such incident is when one of his colleagues on an assignment in Kashmir narrates a story about a crackdown by Indian Army (which was quite common back then) where the locals are lined up to be frisked. The conversation is essentially about how one of the locals was not able to communicate to the soldier that he needed to relieve himself. This had me laughing for two consecutive days just thinking about it.

Critique:

One of my observations was that the book could have done a better job at explaining the motivations of local Kashmiri Muslims behind killing Hindus and eradicating their population, the lack of which might have left a few readers like me high and dry and wanting more, especially if they are already aware of the events that transpired and wanted a more critical approach in understanding the motivations that led the common Kashmiri Muslim to pick up arms against their “Hindu Brethren”.

Now, one might argue that highlighting shortcomings in the Kashmiri Muslim community is not the real intention of the author here. Rather, it being a memoir, his focus is on telling the ordeal of his community. For which, full marks to the author. But I personally feel, being a Kashmiri Hindu myself and naturally having a stake in the matter, any work that highlights the ordeal of Kashmiri Hindus in Kashmir is incomplete without giving the readers some background of the relationship dynamics between Kashmiri Hindus and Muslims over the years. Again, whatever little effort the author has put in this regard is immediately negated by his obsession with romanticizing certain events every now and then, and broad-brushing (may be unintentionally) the cause of these events as some sort of fanaticism that had taken over the Muslim youth just that once.

One of the major issues I take with the book is about its treatment of the Dogra community once the Kashmiri Pandits started pouring over into Jammu. Granted, there were numerous instances of physical and mental harassment that took place initially. But to be charitable to the Dogra community, half of them probably were not even aware at large about what had transpired in Kashmir and the sheer scale of it. With limited resources and limited understanding of the issue not to mention little to no exposure to outside world, certain misunderstandings were bound to happen. Of course, there was exploitation. But where is it not? There was some friction, no doubt, and some unpleasant moments. But the important thing is that they learnt and improved, understood the Kashmiri Hindu culture, people, their trauma and eventually were very accommodating, over time.

I hardly noticed the author using harsh language against Kashmiri Muslims for what they did to his community in this book, but he didn’t think twice before calling a Dogra Hindu “Bus driver” illiterate at one instance. On the other hand, the author, (although in his mind), is addressing the new Muslim owner of his ancestral house back in Kashmir as “Sir”. What is the driver for this bias here, I must ask. The author’s fixation with venting out all his pent-up anger towards “uneducated” Dogra community is too much to bear at times. The author then goes on to talk about bad house renting experiences and lack of proper housing ecosystem, as if Jammu had a very flourishing economy in the early 90s. At various places I feel the book loses the plot and becomes an account of persecution due to xenophobia rather than Genocide. Not to mention, the vague attempt at being “neutral” and “secular” by denouncing the efforts of a certain gentleman in the refugee camp to ignite some sort of self-respect within young and impressionable Kashmiri Hindu kids by telling them the hard truth of Kashmir and reminding them of the fact that it is their Hindu identity that got them kicked out of the valley. The out of place bashing of Hindu nationalistic identity is uncalled for.

Coming back to the film that was based on the book, I fail to understand the outrage against the makers of the film. Most of the heat got deflected towards them, blaming them for intentionally downplaying the part that dealt with the gruesome killings and rapes of Kashmiri Hindus, and trying to present a more neutral picture of the events wherein both the Hindu and Muslim communities are victims and giving benefit of the doubt to the majority Muslim community by implying that they were subjugated and oppressed by the Indian state resulting in the outrage that engulfed the Kashmiri Hindu community.

To be fair to the makers, I think most of the movie is completely based on the book. The empathy that the author has shown at certain places in this book towards his oppressors is a classic example of Stockholm Syndrome. Moreover, by the time one reaches the climax of the book one can’t help but speculate that the author seems to have reached some kind of reconciliation with the said oppressors based on imaginary humanitarian grounds. He never really provides a strong confronting argument against the atrocities committed against his own community. This personal reconciliation should not be mistaken for reconciliation by the entire Kashmiri Hindu community.

Closing Arguments:

The book despite its flaws, creates a strong impact and succeeds to portray the agony of the Kashmiri Hindu community at large yet it somewhat fails to capitalize on crucial elements that could have helped to drive the point home. The point that there is a global Islamic agenda at play. The agenda that fueled the Islamic conquest of Bharat for the past 1200 years. The agenda that led to the partition of Bharat in 1947. The story that conveys not just the atrocities but the causation of events that led to the extinction of the Kashmiri Hindu community from its motherland remains to be told – this book isn’t that.

Leave a Reply