Lord Krishna's words help Arjuna face his fears and fight to protect Dharma.

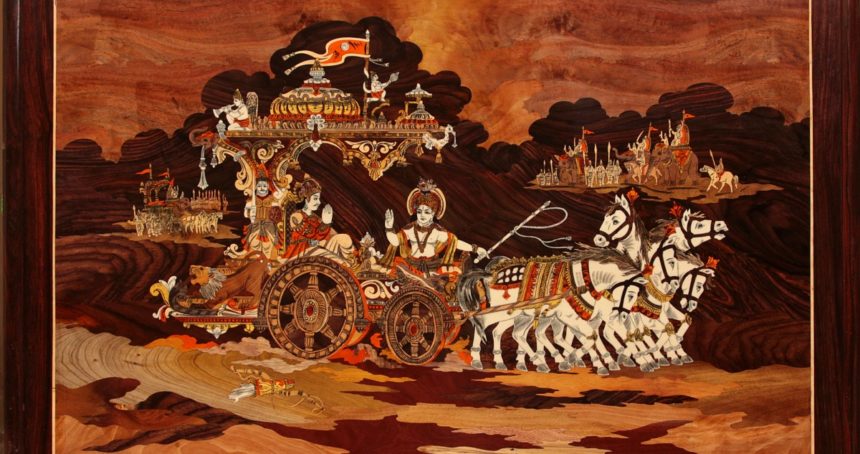

On the most iconic picture in Hinduism (Part II)

When the mammoth and formidable armies commanded by valiant warrior kings, princes and generals of Pandavas and Kauravas was arrayed facing each other in the battle ground of Kurukshatra, Bhishma, the eldest of the Kuru clan blew his conch to announce the beginning of the Mahabharata War. Soon the deafening roar of fighters, the sound of war drums, trumpets and cow-horns filled the sky with a frightening noise. With the beginning of the battle being announced, a confident and eager to fight Arjuna said to Krishna, now his charioteer: “Place my chariot between the two armies so I may see those who stand here for battle and keep it there till I have seen with whom I have to engage in this battle.” [5]

Arjuna’s valor and prowess in battle were legendary. Alone, he could rout an entire army fighting against him. As an archer, his aim was impeccable and he could rain fire with his arrows – a feat which had earned him the epithet: “the scorcher of enemies.” He had fought many battles and had killed many enemies and now, at last, it was his chance to bring to justice the wicked Duryodhana and all those royals who had come to help this evil-minded Kaurava. Lord Krishna placed the chariot at a point between the two armies from where Arjuna could survey both sides at a glance and said to Arjuna: “Behold O Partha (son of Kunti), all the Kurus (your kith and kin) gathered here (in this battle field).”

The fearless Arjuna, who was eager to fight, then saw every member of his royal Kuru clan – grandfathers, uncles, brothers, cousins, sons, nephews, and even teachers and friends – arrayed on one side or the other, ready to battle and kill or be killed in this war. Realizing in a wink that the ensuing blood bath will destroy all of them and ruin their families, the brave but compassionate Arjuna (a Dharmic Arjuna) was overwhelmed by the specter of death and destruction of his kinsmen. Deeply saddened and moved, Arjuna said to Lord Krishna “Seeing these kinsmen arrayed for battle, my limbs give way, my mouth is parching, and a shiver runs through my body. My skin is burning and Gandiva (the bow) slips from my hand. My brain is whirling as it were, and I cannot even stand. I see no good in killing my kinsmen in battle. O Krishna, what will kingdom or luxuries be to us if all those for whom we want those worldly possessions are arrayed here on the battlefield risking their lives? Killing of kinsmen is a sin! Killing them will destroy the purity of our clan and there will be nobody left even to do the ritual offering of water to our departed ancestors (who will fall from their exalted status in heaven). Although greed has made Kauravas blind to the sin of killing friends and relatives, why are we, intelligent and aware of such sins, still set on committing them? It would be better if the sons of Dhritarashtra were to slay me while I was unresisting in the battle.” Saying thus, casting away his bow and arrows, Arjuna sank down in the seat of his chariot.[5]

Lord Krishna was not moved by Arjuna’s concerns of what will happen to his long-departed ancestors masking his weakness due to compassion for his kinsmen – the same kinsmen (the Kauravas) who showed no such concern for the Pandavas. Giving a retort to Arjuna, Lord Krishna asked (Gita chapter 2, verse 2): Kutas tva kasmalam idam visame samupasthitam, Anarya-justam asurgyam akirti-karam Arjuna – “From where has this (unworthy concern) come upon you at this time (when the battle is to begin)? The retort implicitly reminds Arjuna that he came to this battle field for a reason. Had he (Arjuna) forgotten that Kauravas had (1) made an attempt on the life of Bhima? (2) made an attempt on the lives of all of Pandavas, including mother Kunti, by trying to burn them alive in that highly inflammable rest house? (3) attempted to disrobe Draupadi in the royal court? (4) first denied Yudhishthira the throne of Hastinapur and then gave a much smaller portion of the kingdom? (5) invited them to fraudulent gambling and defrauded them of their kingdom sending them into exile for thirteen years? (6) refused to give them back their kingdom after they (the Pandavas) had met all the conditions for it? Was this not the time to bring the Kauravas to justice? And finally, even if all that was forgiven and forgotten, (7) had he (Arjuna) forgotten the duty of a Kshatriya, and a royal, to save his faithful subjects from Kauravas as Adharmic as they had proven themselves to be? Lord Krishna minces no words and tells Arjuna that what Arjuna is doing (excusing himself from the battle,) is “disgraceful, unworthy of an Arya (a nobleman following the Dharmic tradition) and is contrary to the attainment of heaven.”

Continuing with his rebuke at Arjuna’s faint heartedness, Lord Krishna exhorts Arjuna (Gita chapter 2, verse 3): Klaibyam ma sma ghamaha partha, naitat tvayy upapadyate, ksudram hrdaya-daurbalyam tyaktvottistha paranatapa, “Yield not to unmanliness, O son of Pratha (Kunti), cast off this paltry faint-heartedness” and commands him to “stand up” to fight,addressing Arjuna as “O scorcher of thy enemies!” This verse is often cited under the picture shown above. Swami Vivekananda expressed its importance in his own words: “in this one shloka lies embedded the whole message of Gita.[6]

Had Pandavas been fighting only Kauravas, Arjuna might have taken Kauravas destruction in stride. But Arjuna, being a person of conscience, compassion and great character – a Dharmic nobleman – an Arya, he saw an additional dilemma (a Dharma-sankat) and he pleads again with Lord Krishna. Says Arjuna: “But how can I fight (to kill), with my own arrows, my elders like Bhishma and my teachers like Kripacharya and Dronacharaya (who are now part of the army opposing the Pandavas)? They are worthy of my utmost respect! I would much rather live on alms (- a sin for a Kshatriyas, because begging is forbidden for them) than fight them with arrows. Then Arjuna expresses his doubts about this calamitous battle. The Kaurava forces were more than 50% larger than those of Pandava. This disparity is not lost on a warrior like Arjuna. Says Arjuna: We also don’t know whether we would win or the Kauravas would win! And once again talks about worthless gains from all this war: And, even if we were to win, we would still have only these worldly pleasures to enjoy which would be tainted by the blood of those I love! Thus, finding himself in a “Dharma-sankat” – an ethical dilemma, i.e. if he were to fight, he will have to kill those he so highly respects, and if he were not to fight for justice he would be considered a coward (unworthy of an Arya). He begs Lord Krishna to tell him what would be the right course for him because even for the lordship over the three worlds he would not be at peace. Agitated at seeing no honorable way out, his eyes brimming with tears, his limbs trembling and his mind fatigued, Arjuna cast his mighty bow aside and instead of standing up to fight, he sank in the back part of his chariot, saying to Lord Krishna in no uncertain terms: “I shall not fight!”

As if smiling, Lord Krishna addresses Arjuna thus: (Chapter 2, verse 11) Asocyananvasocas tvam, prajna-vadam ca bhasase …” translation: “You worry about those who should not be worried about, and yet talk as an enlightened man!” These few words are heavy with implicit meanings and mark the beginning of the enlightening discourse that is the Bhagavada Gita. It is noteworthy that only humans are endowed with mental capacity to make choices between “right” and “wrong.” And all those warrior-leaders, who had answered the call to battle, for whatever reasons, had made a choice for themselves. They had chosen either to fight on the side of Pandavas (who had been wronged and were fighting for justice for themselves and their subjects) or on the side of Kauravas (who had perpetrated injustice and brought this war on). The facts were known to all. Bhishma, Kripacharya and Dronacharya, were wise men. They knew that Kauravas led by Duryodhana had been unjust to Pandavas. Even the mediation efforts by Lord Krishna had been rebuffed by the Kauravas. Kauravas had not only denied Pandavas their kingdom, they had denied them even a house in which they could live in their own ancestral land! Did those who had joined the Kaurava’s side make a Dharmic choice? And, if they did not, did they still deserve Arjuna’s concern and compassion? That seems to be the implicit meaning in Lord Krishna’s smile and mild retort.

Just because Gita says “Atma is indestructible and the bodies are like clothes that Atma discards at death to get new ones (on rebirth),” does not mean that Gita is cavalier about the value of life. In fact, it is the opposite. “Ahimsa paramo dharma” (translation: non-violence is the greatest Dharma) is the highest guiding principle in Hinduism. However, surrendering to untruth and injustice is cowardice and turning away from battle for justice, even when the opposition holds respected individuals among them, is unworthy of an Arya, seems to be the implicit message here.

The epic “Mahabharata” stands tall, far above the head and shoulders of other works, not because it is the largest epic ever composed, not because it presents a vast web of characters, their personal interests, thinking, machinations and their roles and relationships in a complex society; it is considered greatest and stands so tall because it has the precious golden thread of “Dharma” running through its many stories and personalities separating the right from wrong, the truth from untruth, accomplishing an otherwise impossible task of separating the milk from water, culminating in the Bhagavada Gita. Mahabharata consists of about 100,000 shlokas.[1] The Bhagavada Gita, i.e. Lord Krishna’s advice and instructions to Arjuna, is ensconced in the 700 enlightening verses of it. The Bhagavada Gita, therefore, is a very thin sliver of the epic Mahabharata. However, Bhagavada Gita is to Mahabharata, what life giving Atma is to the body. It is not surprising that the substance and the importance of the Bhagavada Gita are well known to intellectuals everywhere and have been the guiding principles for the brightest of Indian leaders and intellectuals down to modern times.

Another Hindu epic with the golden thread of Dharma running through it, the Ramayana, composed by Maharishi Valmiki predates even Vyasa’s Mahabharata. In the highest tradition of Hinduism, these Maharishis, Valmiki and Vyas, who composed Ramayana and Mahabharata, respectively, had composed these epics first and foremost for their own personal peace and bliss. Goswami Tulsidas, who composed Sri Ramacharitamanasa [7](popularly known as the “Tulsi Ramayan”) in 1574, mentions that time-honored ancient tradition of Maharishis at the very beginning of Tulsi Ramayan: “svantahsukhyai tulasi raghunathgatha bhasanibandhamatmanjulamatanoti ” (translation: Tulsidas writes this story of Raghunatha (Lord Rama) .. for his own joy and bliss.) Goswami Tulsidas pays homage to these sages and explains the importance of their contributions by comparing their acts of composing these great books, Ramayana and Mahabharata, with the acts of great kings who build bridges on vast and formidable rivers (Tulsi Ramayana, Chapter 1: “ati apara je saarita bara jau nrpa setu karanhi, caRhi pipilakau parama laghu binu srama parahi janhi.” (Translation: By building the bridges, the kings also make it possible for even the tiniest ants to cross those mighty rivers with ease.) Implicitly, by composing these epics these Maharishis have constructed bridges over the mighty and turbulent rivers of greed, temptations and passions, etc. And by doing so, they have made it possible for the ordinary folks also, busy with daily lives, to cross those formidable waters to happiness and bliss.

Although, a variety of faiths and opinions among men, formally or informally, have existed since time immemorial, Ramayana and Mahabharata were written for all humanity transcending those divisions. The Dharmic message explained in them is not only for a sect of Hindus or for Hindus in general, it is for anybody who has an open mind. It is that enduring and universal message which is symbolized in the picture “Gitopadesam.”

We are indebted to Goswami Tulsidas again for its explanation. He describes a scene in Chapter 6 (Lanka Kand) of the Sri Ramacharitamanasa which, in essential elements, is similar to one in Bhagavada Gita/Mahabharata. It begins with the Chaupai: “ravanu rathi birath raghubira, dekh bibhishan bhayau adhira,” etc. The scene is set when Vibhishana, a man of Dharmic tradition, a devotee of Lord Rama and a brother of the evil (Adharmic) king Ravana, expresses his concern for the life of Lord Rama, when Vibhishana sees Ravana in full body armor with a variety of weapons in his chariot come galloping towars Lord Rama. And Lord Rama is standing bare feet! He has no body-armor and has no chariot to mount on! Vibhishana entreats Lord Rama: “Lord! You have no chariot, no body-armor or even footwear, how would YOU defeat the mighty foe Ravana?”[7]

Smiling, Lord Rama answers: Listen O’ friend! The chariot that leads to victory is quite another (not the same that Ravana has), and describes that chariot as under:

“Sauraja dhiraja tehi ratha chaka, satya sila drRha dhvaja pataka,

Bala bibeka dama parahita ghore, chama krpa samata raju jore.

Isa bhajanu sarathi sujana, birati carma samtosa krpana,

Dana parasu budhi sakti pracamda, bara bigyana kathina kodamda.

Amala acala mana trona samana, sama jama niyama silimukh nana,

Kavach abheda bipra guru puja, ehi sama bijaya upaya na duja.

Sakha dharmamaya asa ratha jake, jitan kaha na katahu ripu take.”

Translation:

“Valor and fortitude are the (two) wheels of that chariot

Truthfulness and good conduct are its enduring banner and standard,

Strength, discretion, self-control and benevolence are its (four) horses

Forgiveness, compassion, and evenness of mind are the ropes that join them (horses) together.

Adoration of God is the wise driver of that chariot,

Dispassion is the shield, and contentment is the sword,

Charity is the axe, reason the fierce lance

Highest wisdom is the relentless bow,

A pure and steady mind is like a quiver

Quietude and the various abstinences (Yamas and Niyamas) are the sheaf of arrows

Homage to Brahmans and one’s Guru is the impenetrable protective armor.”

“There is no better way than this to get victory

My friend, the one who has such a chariot of Dharma

There is no enemy that he cannot conquer.”

The above is the meaning and universal message of Santana Dharma from Bhagavada Gita/Mahabharata, Ramayana and Sri Ramacharitamanasa etched in the picture above.

A man (“Nara”) represented by Arjuna, needs a chariot of righteousness (consisting of qualities of character described above), but a great chariot alone is not sufficient. A charioteer, i.e. the devotion to Paramatama (“Naraina”), is also needed to counsel the man (Nara) for him to go through the vagaries (battles) of life successfully. Without the charioteer (devotion to Paramatma or Naraina), there will be no victory here, and salvation hereafter, for the man (Nara).

Sanjay, who became the eyes of the blind king Dhritarashtra to keep him informed of the happenings on the battlefield at Krukshetra finally declared to Dhritarashtra: “Yatra yogesvarah krsno yatra partho dhanur-dharah, tatra srir vijayo bhitir dhruva nitir matir mama” (Translation: It is my firm conviction that wherever is Lord Krishna and, wherever there is Arjuna – the wielder of the bow, Goodness, Victory, Glory and unfailing Righteousness are there.)

Bhagavada Gita emphasizes doing one’s duty according to one’s Dharma, with dedication and equanimity of mind – the Karma Yoga. But the picture “Gitopadesam” addresses not only Karma Yoga, but also the Gyan Yoga and the Bhakti Yoga. Noticeably, there is no mention of astrology in the discourse between Arjuna and Lord Krishan – i.e. Bhagavada Gita. It is no surprise that the picture titled “Gitopadesam” is the most iconic for all Sanatana Dharma (loosely called Hinduism). It is not merely a scene from Mahabharata, it is the embodiment of the core message of Santana Dharma/Hinduism which is universal in nature and transcends religious divides.

References:

1. Mahabharata, in ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HINDUISM, Vol. VI, 2011. India Heritage Research Foundation, Rupa & Co., New Delhi.

2. MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari, compiled and edited by Jay Mazo, http://www.gita-society.com/section3/mahabharata.htm

3. Mahabharata Story-Summary, Suryaprakash Verma, 2014. http://www.allaboutbharat.org/post/Mahabharat-Story-Summary

4. Mahabharata, From Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahabharata

5. SRIMAD BHAGAVADA GITA, With Sanskrit text and English translation by Jayadayal Goyandka, 1969. Gita Press, Gorakhpur.

6. AN INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF THE GITA by Swami Ranganathananda, 1991. Advaita Ashram Publication, Calcutta.

7. SRI RAMACHARITAMANASA by Goswami Tulsidas, 1575. Reprinted by Gita Press, Gorakhpur. With Hindi Text and English Translation (A Romanized Edition)

Leave a Reply