India's laws are still stuck in the colonial era where natives were not considered good enough to manage their own institutions.

Let’s have some faith

In the opinion piece, “Who would you rather have run our temples?” (Deccan Herald, 30 May 2021), the author may believe he is asking the Hindu community a straightforward question of making the choice between two evils, the lesser of which is state intervention and restraint of the fundamental right to freedom of religion under the Constitution. Yet, the debate is far more nuanced than that, and it would be a travesty of secularism to let a deferential standard for the State’s assault on religious freedom go unquestioned.

The piece makes three main arguments in pursuance of the same. Firstly, that the bitter disputes between the community over Hindu temples, their property and management have raged on in court for one and a half millennia leading to a public policy concern for state management of temples. Secondly, state intervention was brought to prevent mismanagement within these institutions and to protect temple property from theft and misappropriation. Thirdly, the management of religious institution’s property is a matter of law and not religion. Let us take the arguments, point by point.

Fighting within Hindu Groups

When our ancestors fought for independence, they faced similar imperialist rhetoric that rights are only meant for those who are deemed capable of civilizing their conduct and ruling themselves. In true colonialist fashion, these grounds for capability were determined by the Crown itself and thus served to bind the Indian people by the liberal universalism of secular laws and yet kept them outside its protection. Legal scholar Antony Anghie in 2006 wrote about the colonial underpinning of international law, where the doctrine of sovereignty first expelled the “uncivilised” non-European communities from its realm and then justified imperialism as the process through which violent and backward non-Europeans could be incorporated into international law as independent, sovereign actors. Today, to say that a community can exercise the right to manage its own religious institutions only when it can show that there is absolute as well as continuous uniformity in beliefs and practices without dissension within itself means to impose upon institutions of Hindu communities (or for that matter, any religious community with similar experience) the diktat of a secular State and yet deny them the protection of secularism. A similar hegemonic rhetoric underlies the Supreme Court’s insistence on applying an Oxford dictionary definition for religious denomination over the more indigenously appropriate meaning of sampradaya to Hindu religious institutions.

Coming back to infighting between Hindu groups, it is not the mandate of the Constitution that rights of only those individuals and groups which are non-litigious shall be protected against the wrath of the State. Indeed, it is antithetical to the idea of rights in a democracy that such criteria should be innovated since rights only have meaning when citizens can enforce them in court (which is the reason why approaching the Supreme Court to uphold one’s rights is itself a fundamental right under Article 32). Even if it can be shown that litigiousness is actually working to erode the guarantee of religious freedom under Article 25 to 28 (which is a tenuous claim since it would imply that the Supreme Court and High Courts are not fulfilling their mandate in terms of the matters they decide to hear and the orders and judgements they pass while deciding such matters), the responsibility for the same lies with the state machinery and its laws, and the appropriate response cannot be to deprive an entire community (and its forthcoming generations) of their legitimate rights under the Constitution.

In any case, the author himself states that bitter disputes have ‘afflicted’ every religion in India, which would make the management of religious institutions a dire public policy concern. Yet, it would be no one’s argument that religious institutions of other communities should also be placed under state control. This is because in liberal legal thought, we recognise the Rawlsian conception of rights as trumps over public policy concerns of the State. It is quite astonishing that the same is not extended to the Hindu community and their temples.

State Intervention is needed to prevent mismanagement

That a community is so incapable of managing its religious institutions that the State must mandatorily take over and manage them for that community is a paternalistic argument that India is not new to. This assertion has previously ravished India’s industries, education systems, justice administration and indeed the country’s own sovereignty. It continues to afflict India’s temples, where post-independence the State has taken over more than a lakh temples, without distinguishing between the big and small, in the five states of southern India alone. Nearly every state in the country has a legislation governing the administration and functioning of a major temple in its territory.

You name a major Hindu shrine, chances are that it is run by the State. And yet, the State did not build them. By its secular mandate, it is required to be apathetic towards the religious affairs of communities. That begets the question, with what ground can it then believe that it is better suited to look after God’s home than the devotees of God themselves? Regulation of any institution must be done by those who have its best interests in mind and those who have skin in the game. Some may argue that it is ultimately Hindu government functionaries who manage these temples, sometimes the same is even mandated by law, and hence the temples are still being managed by members of the faith.

Yet, this logic misconstrues qualifications for the management of temples to be binary in nature, with the individual being a believer in the faith or not. In reality, there is a gradation between these two extremes as the extent and depth of belief as well as capability to discharge functions varies from person to person. Hence, even among worshippers or believers of the faith, those who are best suited for the management committee should be selected. This sort of selection, arguably, can only be done by a person who believes in the faith and not by someone who is antagonist or apathetic to it.

At the risk of drawing ire for equating temple administration with justice administration, I draw your attention to the Supreme Court decision in the National Judicial Appointments Committee case of 2015, where the top court struck down a law that sought to replace the current collegium system with a committee for appointment of judges. This committee was to comprise of executive, judicial and eminent civil society members, and while criticising the inclusion of lay “eminent persons”, the court noted that it is not only important that a “wrong person” not be appointed as a judge but also that those who are appointed are the ‘best talent’ amongst the country’s lawyers, judicial officers and jurists for which primacy of the judiciary in appointment of the judges was necessary. The court here, correctly, recognised that in order to preserve the values and atmosphere of the judiciary, it is the institution itself that needs to be in overall control of the appointment of its functionaries. Similarly, to preserve the values and atmosphere of temples in India, the community should be in control of appointments of the temple management, and not the State, because only the community will be able to appoint the best-suited members of their faith to run their temples.

The State has had control over Hindu temples for more than sixty years since independence. All this while, the temple resources are not being invested for furthering the temple’s philosophy or tradition, but for non-temple, non-religious purposes such as running of public infrastructure schemes and lending loans to the state government at minimal rates of interest. At the same time, temple priests are being paid a pittance in the name of salary and devotees’ access to darshan and prayer rituals in the temple is commercially bifurcated on their ability to pay or their VIP status. Perhaps even a Socialist State learns a thing or two about capitalism when it comes to Hindu religious institutions.

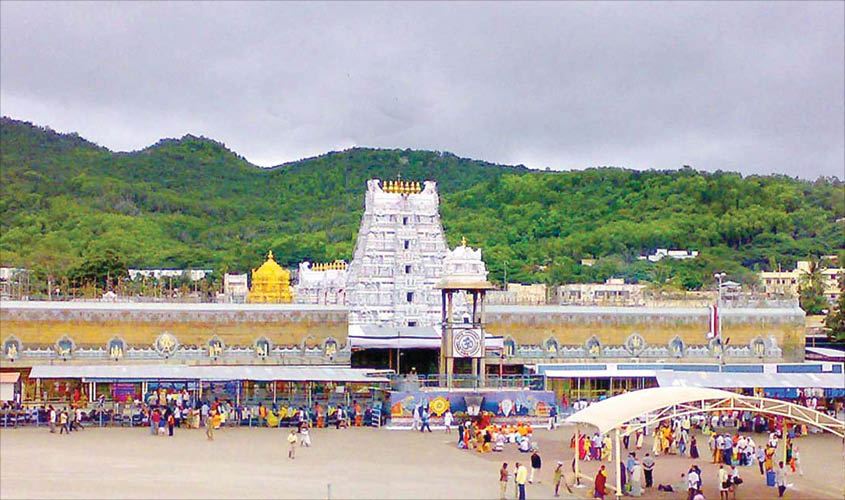

Many temples are several hundred years old; in order to maintain authenticity and continuity in the cultural heritage, they require careful maintenance according to scriptures and practice on temple architecture. Today, they are not only left to decay by barring any involvement of the community but also the apathy in any ‘conservation’ and reconstruction work by government departments is heart-breaking. The list includes largescale whitewashing of ancient murals and sandblasting ancient sculptures in thousand-year-old Chola temples, gold-plating over ancient inscriptions in the Tirupati mandir, and felling of the ancient Akshay Vat tree which is the abode of Lord Hanuman in Kashi.

If that wasn’t enough, there is rampant corruption, smuggling and theft of ancient murtis by the government officials. The HR&CE department of Tamil Nadu has itself admitted to the Madras High Court the theft of 1,200 statues between 1992 and 2017 where only 56 cases were solved and possession was returned in only 18 cases. In most cases, the complaints were closed after the police declared the murtis untraceable.

Imagine appointing a caretaker for your own ancestral village, who tells the stories of your family that grew and lived there for generations. Would you appoint someone who refuses to show concern towards the cultural heritage of the place, sells acres of property to illegal encroachers or chooses to invest all its resources in neighbourhood development whilst your house own crumbles? Temples are our collective ancestral heritage. These are places that our ancestors built, adored and protected with their lives for over centuries, and we have elected governments that plagued them with ruin within decades.

Management of Temples is a matter of Law

The author uses the early 1950s case of Commissioner v Shirur Math to argue that the Constitution differentiates between the administration of religious property under Article 26(d) and the right to manage religious affairs under Article 26(b). However, even in Shirur Math, the court only holds that the State can regulate the administration of the temple through the law, without giving the State itself the power to take over the administration of the temple by enacting the law. Aside from the fact that many provisions struck down in Shirur Math were reintroduced in a 1959 law on the same matter, it is important to note that secular functions of temple management do not exist in isolation, and rather create the environment for religious functions. The secular functions have the potential for promoting or marring religious functions.

While the author states that religious institutions are custodians of immense wealth and influence, it is important to note that the same is by virtue of the religion itself and not due to any secular reason that can legitimise state takeover. The manner in which the State manages temple property and resources directly affects the religious affairs of the temple and the conduct of daily worship, festivals and ceremonies. It cannot be the case that the Constitution intends such regulation to cause detriment to the institution’s functioning, property and heritage.

Further, unlike the author’s interpretation, the Shirur Math case is not one where the court balances citizens’ right to religious freedom against an ostensible ‘right’ of the State to “stop mismanagement”. Conceptually, rights are meant to protect citizens against State authority and not vice versa because in liberal thought the sovereign State has a monopoly over violence and thereby an inherent power differential is believed to exist between the State and its citizens.

Rather, what Shirur Math does is reaffirm the limits on state interference by holding that freedom of religion can only be restricted on grounds specified under Article 25 and 26. For the majority of the temples under state control today, none of these grounds are ever proved to have existed before the takeover.

In any form of state interference, the role of the government is that of a custodian of citizens’ rights. So long as it is functioning to the benefit and promotion of these rights, it is acceptable for such state control to continue. However, the state, in the guise of only legislation, cannot be justified to actively act against religious freedom rights guaranteed under the Constitution. The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that taking over religious institutions by the government can only be a temporary measure in order to remedy any maladministration of property and not for perpetuity. It is imperative that the government take note of the same, and a mechanism for the exit of State from temple administration is given a serious thought. Finally, lest anyone argue that without the State we risk confusion and chaos to take over, it is important to note that several ideas have already been proposed. It’s time we ditch the deference to State subjugation and join the conversation to match our diverse temples with suitable models for community management.

Leave a Reply