In any colonial domination, the conqueror is often more profoundly influenced by the conquered than he could have anticipated. India’s influences on British, American, German philosophers, writers, poets and artists were considerable and have been well documented. But it is often overlooked that for much of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, India was an object of fascination and at times reverence in Europe’s cultural centre — France. There are several reasons for this lack of awareness: among them, the language barrier, France’s limited physical presence in India during the colonial era, and also, in the twentieth century, what Roger-Pol Droit has called “the oblivion of India” (1) — an oblivion which may be about to come to an end.

This paper briefly examines some of the main channels of India’s influence on French literature and thought, and attempts to make out the curve now unfolding.(2)

The Pioneers

Before the mid-eighteenth century, contacts between France and India were few and far between, and most accounts of the Indian subcontinent were highly fanciful. “Les Indes” (“Indias”) were synonymous with a mysterious, ill-defined remote region full of half-monstrous creatures at worst, crude savages on the whole, and enigmatic naked “gymnosophists” at best — the perfect antithesis of Europe. The chief discernible Indian influence in that period, albeit through Arab and Greek intermediaries, was that of the Panchatantra on La Fontaine’s celebrated Fables, which also featured animals to draw lessons on human nature and behaviour.

Things started changing as the colonial race warmed up. Travellers became more frequent, less inventive, and brought back more and more reliable material — including, in 1731, the first complete manuscript of the Rig-Veda (in Grantha script), deposited with the Royal Library in Paris. However, this treasure would not be recognized for decades, as no one in Europe could read Sanskrit till the 1780s.

Thus the first serious French writers on India had to sift through travellers’ accounts and rely on scraps and pieces — sometimes on forgeries too. Such was the well-known case of Voltaire, who was convinced that the Ezour-Vedam brought to him in 1760 by a traveller was the genuine Veda: it was, in reality, a fabrication by French Jesuits in Pondicherry with a view to denigrating Indian “idolatry” and indirectly establishing the superiority of Christianity. But nothing was to deter Voltaire in his enthusiasm for most things Indian and his abhorrence of all things Judeo-Christian: he managed to use the Ezour-Vedam to prove the superiority of Indian wisdom! In fact, it is surprising how, with so little genuine material on his hands, he intuitively perceived India’s contributions to civilization:

I am convinced that everything has come down to us from the banks of the Ganges, astronomy, astrology, metempsychosis, etc….(3) The Greeks, in their mythology, were merely disciples of India and of Egypt.(4)

Voltaire’s fascination led him to write a whole essay, Fragments historiques sur l’Inde (1773), and to devote to India two chapters of his influential Essai sur les moeurs et l’esprit des nations, where we read this unexpected thought:

If India, whom the whole earth needs, and who alone needs no one, must by that very fact be the most anciently civilized land, she must therefore have had the most ancient form of religion.(5)

Showing himself to be well ahead of his times, Voltaire also repeatedly criticized Europe’s greed and brutality in the colonization underway:

We have shown how much we surpass the Indians in courage and wickedness, and how inferior to them we are in wisdom. Our European nations have mutually destroyed themselves in this land where we only go in search of money, while the first Greeks travelled to the same land only to instruct themselves.(6)

In many ways, Voltaire the sceptic, the champion of reason, opened in France the first door to India. Among others, Diderot, the mainstay of the epoch-making Encyclopédie, included in it a few serious and sympathetic articles about Indian religion and wisdom. By offering an alternative, however hazy at first, to the biblical worldview (and a chance to cock a snook at the Church), by showing that Greco-Roman, Hebrew-Christian Europe did not have the monopoly of wisdom or civilization, India provided such thinkers with ammunition and indirectly nurtured the new currents of thought that were going to upset the neo-classical, but still deeply Christian order.

The Romantic Craze for India

French travellers to India in the second half of the eighteenth century left important and wide-ranging testimonies: Jean-Baptiste Gentil, A. Anquetil-Duperron, A. de Polier, Pierre Sonnerat among many others,(7) most of whom, like their British counterparts, saw in India the cradle of humanity, and in Indians the gentlest of people. Anquetil-Duperron’s Latin translation (in 1801) of fifty Upanishads from a Persian version was long the only one available in Europe, and the one that so struck Schopenhauer. Soon, British and German scholars started unlocking the secrets of Sanskrit. In 1814 France created its first chair of Sanskrit at the Collège de France, and the Société asiatique de Paris was born in 1821 (two years before London’s). Eminent “Orientalists” such as Eugène Burnouf, De Chézy, Langlois or Barthélémy-Saint-Hilaire dipped into the numerous Indian manuscripts accumulated at the Bibliothèque nationale (the National Library, formerly Royal Library), and founded the French school of Indology that was to continue in the twentieth century with the likes of Sylvain Lévi, Louis Renou,(8) Jean Filliozat, Olivier Lacombe, Jean Varenne and many others.(9)

But more than the Vedas, Panini, the Laws of Manu or Buddhist texts, it was the first translations of the two great Indian epics and of Kalidasa’s works (especially his Shakuntala), also the Gita and a few Upanishads, that kindled the imagination of nineteenth-century France’s intelligentsia, especially the Romantics. Those texts were widely read, feverishly exchanged, avidly commented upon.

Victor Hugo, half attracted, half repelled by Asia, perhaps more at home in an Arabian Orient, dotted his vast work with Indian themes and gods, composed a whole poem (“Suprématie”) based on the episode of the Kena Upanishad that sees Agni and Vayu failing to conquer a blade of grass, and declared:

Oriental studies have never been so intensive…. In the century of Louis XIV one was a Hellenist, today one is an Orientalist…. The Orient has become a sort of general preoccupation…. We shall see great things. The old Asiatic barbarism may not be as devoid of higher men as our civilization would like to believe.(10)

Edgar Quinet, a strongly anticlerical historian, venerated India:

India made, more loudly than anyone, what we might call the “declaration of the rights of the Being.” There, in this divine self, in this society of the infinite with itself, lies clearly the foundation, the root of all life and all history.(11)

Quinet foresaw for Europe an “Oriental Renaissance,” which was to have a greater impact than that of the sixteenth century. His more renowned friend Michelet, the prolific chronicler of France’s history, went deeper. Nothing moved him so much as the Ramayana, and his outburst in La Bible de l’humanité deserves to be quoted at some length:

The year 1863 will remain cherished and blessed. It was the first time I could read India’s great sacred poem, the divine Ramayana…. This great stream of poetry carries away the bitter leaven left behind by time and purifies us. Whoever has his heart dried up, let him drench it in the Ramayana. Whoever has lost and wept, let him find in it a soothing softness and Nature’s compassion. Whoever has done too much, willed too much, let him drink a long draught of life and youth from this deep chalice…. Everything is narrow in the Occident. Greece is small — I stifle. Judea is dry — I pant. Let me look a little towards lofty Asia, towards the deep Orient. There I find my immense poem, vast as India’s seas, blessed and made golden by the sun, a book of divine harmony in which nothing jars. There reigns a lovable peace, and even in the midst of battle, an infinite softness, an unbounded fraternity extending to all that lives, a bottomless and shoreless ocean of love, piety, clemency. I have found what I was looking for: the bible of kindness. Great poem, receive me!… Let me plunge into it! It is the sea of milk.(12)

Hugo, Quinet and Michelet were part of the Romantic movement in one way or another. So were the poets Lamartine, de Vigny, Leconte de l’Isle, and many others who all liberally drank deep at India’s fountains, some to the point of inebriation. Lamartine, for instance, said of Hindu philosophy,

“It is the Ocean, we are but its clouds…. The key to everything is in India.”(13)

The symbolists also found their inspiration stimulated and expanded by the new world India offered them: Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Verlaine (who wrote a poem on “Çavitri”), Rimbaud, the “accursed poets” like Nerval or Lautréamont. Some of France’s best-known novelists followed suit, from Balzac to Jules Verne (who located a whole novel, La Maison à vapeur, in India). Rodin lavished praise on bronzes of Shiva’s dance. The mood was decidedly oriental and the nineteenth century saw a strong presence of India in France’s creative life and imagination.

The Twentieth Century

But France’s exploration of India remained superficial. A generous adhesion of the heart, the emotions and the aesthetical sense, but a lack of intellectual moorings to avoid drifting on the “Indian Ocean.” Few French philosophers, for instance, felt the Indian wave, with notable exceptions such as Renouvier or Taine. (14) Hindu and Buddhist thought and message did not integrate into French thinking, except for a few distant echoes here and there, for instance in Bergson, whose defence of intuition would surprise no Indian. Thus, with the reaction against Romanticism and the utilitarian and materialistic trends precipitated by the two World Wars, India receded into the background.

Still, her indirect influence could be felt in Surrealism, its search for a higher reality and its rejection of blind chance. She had spokesmen of varying talent in Romain Rolland (with his famous lives of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda), René Daumal,(15) Maurice Magre or René Guénon. Henri Michaux put India’s inner quest at the centre of his poetry; André Gide translated Tagore’s Gitanjali into French. André Malraux read the Gita in the original, visited India several times, was fascinated by her art, and probably understood her central message better than any of his contemporaries (with the exception of Daumal):

… The deepest opposition [between the West and India] rests on the fact that the fundamental evidence of the West, whether Christian or atheist, is death, whatever meaning the West gives to it, whereas India’s fundamental evidence is the infinite of life in the infinite of time: “Who could kill immortality?”(16)

Indeed, Malraux’s conversations with Nehru and his almost naive attempts to draw the latter back to India’s roots make poignant reading.(17)

Despite such great names coming to her rescue, India’s slide continued in the French mind, even as some of her thoughts became so internalized as to be unrecognizable. Her epics or sacred texts were no longer in fashion with French students, and French Indologists became an isolated circle on the margins of the academic mainstream. Materialism reigned supreme, with a tinge of Christianity here and a dash of Marxism there; it had no more use for “mysticism,” especially of the Oriental kind. “The whole earth” no longer needed India, at least France did not. Non-European cultures were, once again, regarded as inferior and unworthy of study, except at best to satisfy a momentary curiosity. Even today the French educational system, moulded in that attitude, gives them virtually no place. Roger-Pol Droit has eloquently shown(18) how a French teacher or professor of philosophy will likely be perfectly ignorant of thought systems originating from India; to them, all begins in Greece and nowhere else.

Something of a reaction took place after World War II, perhaps precisely because the War confronted Europe with a radical failure of its ideals of humanism and pacifism. Several sympathizers of India had a significant impact: Arnaud Desjardins, Alain Daniélou, Alexandra David-Neel, Jean Herbert, Guy Deleury or Jean Biès deserve mention, among many others. From the epics or Shakuntala, the vogue now turned to the words and writings of India’s living yogis, for instance, Sri Ramakrishna, Swami Vivekananda, Sri Aurobindo, Ramana Maharshi, Swami Ramdas, Ma Anandamayi. Among them, right from 1914 when he published his monthly Arya in both English and French editions, Sri Aurobindo was a crucial — but discreet — bridge between India and France, and probably the only Indian seer ever to be formally honoured at the Sorbonne.(19) His vision of evolution and his method of integral yoga appealed not only to the aspiring heart but to the intellect weary of the shallowness of Western psychology or the brilliant but ephemeral edifices of existentialism, structuralism, poststructuralism, modernism, postmodernism, deconstructionism, and the endless sequence of isms and post-isms built upon each other’s ruins. Sri Aurobindo thus prepared the ground for a renewed acceptance of non-Western thought; Mother, his French-born companion, kept the stream living.(20)

All these undercurrents resurfaced powerfully in the 1960s in the wake of the so-called New Age, which in France represented a determined, if clumsy and mixed, challenge to the rule of Cartesianism. As a popular movement, it chafed at the inadequacies of Western ideas, ideals, culture and society, and once again looked eastward. Hatha yoga and various meditation techniques spread, so did Buddhism whether Tibetan or Zen. (Let us note that since the 1990s, Buddhism has become the “fastest-growing religion” in France, although its followers generally do not view it as a formal religion, rather as a practical method for self-discovery.) A whole literature exploded (pioneered in part by the famous magazine of the 1960s,Planète), producing a cocktail of yoga, esotericism, health techniques or search for past lives.

A good deal of distortion, appropriation and misappropriation followed, but that was unavoidable, especially when France’s academic and scholarly milieu was so unmindful of India, and when in addition Indian intellectuals interacting with France often appeared tied to the apron strings of a Sartre, a Lacan, a Foucault or a fashionable Derrida.

Today … and tomorrow?

In the last few years, however, a new development seems to have started. More and more serious scholars have taken to writing about India.(21) Some of the old misconceptions or preconceptions remain, although less stained with a sense of European superiority than in the nineteenth century, more imbued with a sincere effort to understand this world apparently so different, yet so intimate at times. At the very least, it means that the old fascination with India’s heritage is not dead; it is reviving with fresh vigour and finding new voices.

If, in these times of monocultural magma, a nation still symbolizes some aspect of the human spirit, then France represents the higher intellectual quest, and also an élan in the adventure of self-discovery. That is what makes its encounter with India so pregnant with possibilities: Is the human mind doomed to forever turn in the same circle, catching no more than one new glimmer of the Truth at every turn? Or can it muster enough honesty and humility to acknowledge its intrinsic incompleteness and the need for a higher consciousness to lead it beyond this stumbling from semi-error to semi-truth, beyond this irremediable incapacity to fulfil man’s potential? Can it finally open itself so much as to grasp what exceeds it — a vaster, more essential quest that India symbolizes?

That, beyond all Indological learning, is the question raised by the meeting of France and India; it is the question that impelled a Voltaire, a Michelet or a Malraux. The bridge will have to be strengthened and broadened if the common deeper roots of India and Europe are to be nourished and if the West is to rediscover a durable foundation for its culture. India can choose to help in the process: the timeless creator and tireless giver she is should shed her passivity and effectively project all that is precious in her heritage; when her own intelligentsia is today failing so dismally in this task, it is not just “the whole earth that needs India,” but also India that does need some fraternal comprehension from other cultures, because her central preoccupation was always the very essence of what culture is all about.

References / Footnotes

1. Roger-Pol Droit, L’oubli de l’Inde — Une amnésie philosophique (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1989).

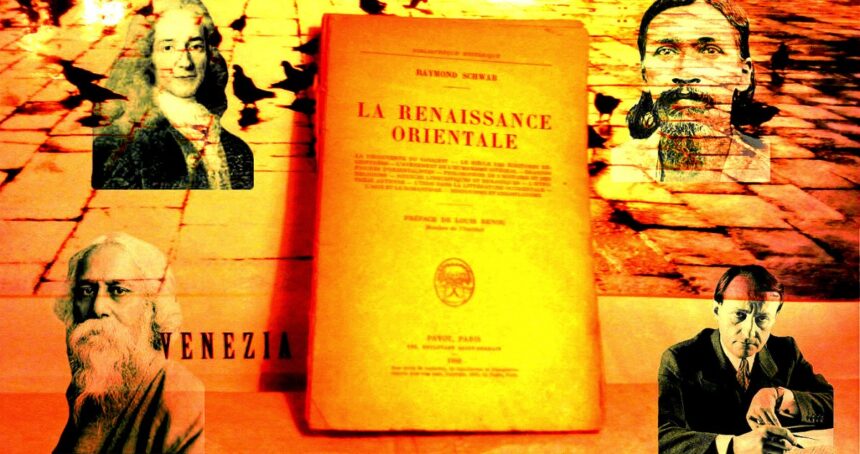

2. I have referred to a number of works, but two stand out in the field: (1) Raymond Schwab’s remarkable and wide-ranging La Renaissance orientale (Paris: Payot, 1950); I have not seen its English translation, The Oriental Renaissance: Europe’s Rediscovery of India and the East 1680-1880 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), which is said to be below par; (2) Jean Biès, Littérature française et pensée hindoue des origines à 1950 (Librairie C. Klincksieck, 1974) which, to my knowledge, is unfortunately yet to be translated into English. Note that in this paper, English translations of passages originally in French are mine.

3. Voltaire, Lettres sur l’origine des sciences et sur celle des peuples de l’Asie (first published Paris: 1777), letter of 15 December 1775.

4. Quoted in Les Indes Florissantes — Anthologie des voyageurs français (1750-1820), by Guy Deleury (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1991), p. 663.

5. Voltaire, Essai sur les mœurs et l’esprit des nations (Paris: Bordas, Classiques Garnier, 1990), p. 237.

6. Voltaire, Fragments historiques sur l’Inde (first published Geneva: 1773), in Œuvres Complètes (Paris: Hachette, 1893), vol. 29, p. 386

7. An excellent collection of such testimonies can be found in Les Indes Florissantes — Anthologie des voyageurs français (1750-1820), op. cit.

8. Louis Renou and Jean Filliozat authored a masterly study of classical India, which remains a much consulted reference: L’Inde classique — Manuel des études indiennes(volume I: Paris: Payot, 1947, republished Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient, 1985; volume II: Paris: École française d’Extreme-Orient, 1953, reprinted 2001).

9. Louis Renou gives a brief account of French Indology in “The Influence of Indian Thought on French Literature” (Madras: Adyar Library Bulletin, vols. XII & XIII, reprinted in the Adyar Library Pamphlet Series No. 15 in 1948). See also “Indian Texts, French Translations: France’s Contribution to Indology” by Michel Danino (unpublished, 2003).

10. Quoted by Jean Biès,op. cit., p. 108.

11. Ibid, p. 100.

12. Michelet, La Bible de l’humanité , volume 5 of Œuvres (Paris: Bibliothèque Larousse, 1930), p. 109-110.

13. Lamartine, Opinions sur Dieu, le bonheur et l’éternité d’après les livres sacrés de l’Inde (Paris: Sand, 1984), p. ix.

14. See two essays by François Chenet and Roger-Pol Droit on these philosophers in L’Inde inspiratrice — Réception de l’Inde en France et en Allemagne (XIX e & XX e siècles), eds. Michel Hulin and Christine Maillard (Strasbourg: Presses Universitaires de Strasbourg, 1996).

15. René Daumal, author of the well-known Mount Analogue, went deeper than many, studied Sanskrit and mastered it to the point of writing a grammar for it. His plans to translate large portions of Sanskrit literature were cut short by his premature death in 1944, at the age of 36. His penetrating essays on Indian drama, music and poetry, as well as a few translations from the Veda and other texts, were collected in Bharata — L’origine du théâtre, la poésie et la musique en Inde(Paris: Gallimard, 1970).

16. André Malraux, Antimémoires (Paris: Gallimard, 1957), p. 339.

17. See, in addition to Antimémoires, the well-documented bilingual Malraux & India: A Passage to Wonderment (New Delhi: Ambassade de France en Inde, 1996).

18. See note 1 above.

19. See Séance commémorative de Sri Aurobindo à la Sorbonne le 5 décembre 1955 presided over by Jean Filliozat (Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram). Several collections of articles paid tributes to Sri Aurobindo, e.g. “Hommage à Shri Aurobindo” in France-Asie (Saigon: Nos. 58 & 59, March and April 1951) and “Hommage à Sri Aurobindo” Synthèses (Bruxelles: December 1965).

20. Satprem’s Sri Aurobindo et l’aventure de la conscience(Paris: Buchet-Chastel, 1971; in English: Sri Aurobindo or the Adventure of Consciousness, Mysore: Mira Aditi, 2000) provides an excellent introduction to Sri Aurobindo and Mother.

21. Among the numerous books published in France or in French about India, and in addition to a few titles already above, I mention here chronologically a few recent ones (without offering any assessment): Guy Deleury, Le modèle indou(Paris: Kailash Éditions, 1993); Jean Biès, Les chemins de la ferveur (Lyon: Terre du Ciel, 1995); Kama Marius-Gnanou, L’Inde(Paris: Éditions Karthala, 1997); Jacques Dupuis, L’Inde — Une introduction à la connaissance du monde indien(Paris: Kailash Éditions, 1997); Jean Biès, Les grands inités du XX e siècle (Paris: Philippe Lebaud, 1998); François Gautier, Un autre regard sur l’Inde(Genève: Éditions du Tricorne, 1999); Odon Vallet, Les spiritualités indiennes (Paris: Gallimard, 1999); Ysé Tardan-Masquelier, L’hindouisme — Des origines védiques aux courants contemporains (Paris: Bayard Éditions, 1999), Guy Sorman, Le génie de l’Inde (Paris: Fayard, 2000); Guy Deleury, L’Inde, continent rebelle(Paris: Seuil, 2000); Jackie Assayag, L’Inde — Désir de nation(Paris: Éditions Odile Jacob, 2001); Michel Angot, L’Inde classique (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2001); Jean-Claude Carrière, Dictionnaire amoureux de l’Inde (Paris: Plon, 2001).

Leave a Reply