Continuing from India’s Ancient Maritime History – Part 1 where we looked at various historical accounts about the ingenuity and superiority of India’s maritime prowess.

Ancient India’s maritime trade

Further evidence shows that shipping from Bharatvarsha was a national enterprise and the country was a leader in world trade relations amongst such people as the Phoenicians, Jews, Assyrians, Greeks, and Romans in ancient times, and more recently with Egyptians, Romans, Turks, Portuguese, Dutch, and English.

The simple fact is that India’s maritime history predates the birth of Western civilization. The world’s first tidal dock is believed to have been built at Lothal around 2300 BCE during the Harappan civilization, near the present day Mangrol harbor on the Gujarat coast.

The earliest portrayal of an Indian ship is found on an Indus Valley seal from about 3000 BCE. The ship is shown being elevated at both bow and stern, with a cabin in the center. It is likely to have been a simple river boat since it is lacking a mast. Another drawing found at Mohendjodaro on a potsherd shows a boat with a single mast and two men sitting at the far end away from the mast. Another painting of the landing of Vijaya Simha in Ceylon (543 BCE) with many ships is found amongst the Ajanta caves.

That India had a vast maritime trade, even with Greece, is shown by the coins of the Trojans (98-117 CE) and Hadrians (117-138 CE) found on the eastern coast of India, near Pondicherry. This is evidence that Greek traders had to have visited and traded in the port cities of that area.

Kamlesh Kapur explains more about this in Portraits of a Nation: History of India:

“Recent archeological excavations at Pattanam in Ernakulum district of Kerala by the Kerala council for Historical Research (KCHR) indicate that there was thriving naval trade around 500 B.C.

According to the Director of KCHR,

‘The artifacts recovered from the excavation site suggest that Pattanam, with a hinterland port and a multicultural settlement, may have had links with the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea, and the South China Sea rims since the Early Historic Period of South India.’

KCHR has been getting charcoal samples examined through C-14 and other modern methods to determine the age of these relics. These artifacts were from the Iron Age layer. The archeologists also recovered some parts of a wooden canoe and bollards (stakes used to secure canoes and boats) from a waterlogged area at the site.

“The radiocarbon dating from Pattanam will aid in understanding the Iron Age chronology of Kerala. So far, testing done by C-14 method to determine the ages of the charcoal samples from the lowermost sand deposits in the trenches at Pattanam suggests that their calibrated dates range from 1300 B.C. to 200 B.C. and 2500 B.C. to 100 A.D. Thus there is strong evidence that Kerala had sea trade with several countries in Western Asia and Eastern Europe from the second millennia B.C. onwards.” 1

The influence of the sea on Indian Kingdoms continued to grow with the passage of time. North-west India came under the influence of Alexander the great, who built a harbor at Patala where the Indus branches into two, just before entering the Arabian sea. His army returned to Mesopotamia in ships built in Sindh. Records show that in the period after his conquest, Chandragupta Maurya established an admiralty division under a Superintendent of ships as part of his war office, with a charter including responsibility for navigation on the seas, oceans, lakes and rivers. History records that Indian ships traded with countries as far as Java and Sumatra, and available evidence indicates that they were also trading with other countries in the Pacific, and Indian Ocean. Even before Alexander, there were references to India in Greek works and India had a flourishing trade with Rome. Roman writer Pliny speaks of Indian traders carrying away large quantity of gold from Rome, in payment for much sought exports such as precious stones, skins, clothes, spices, sandalwood, perfumes, herbs, and indigo.

The port cities included such places as Nagapattinam, Arikamedu (near Pondicherry), Udipi, Kollam, Tuticorin, Mamallapuram, Mangalore, Kannur, Thane, and others, which facilitated trade with many foreign areas, such as Indonesia, China, Arabia, Rome, and countries in Africa. Many other inland towns and cities contributed to this trade, such as Madurai, Thanjavur, Tiruchirapalli, Ellora, Melkote, Nasik, and so on, which became large centers of trade. Silk, cotton, sandalwood, woodwork, and various types of produce were the main items of trade.

Trades of this volume could not have been conducted over the countries without appropriate navigational skills. Two Indian astronomers of repute, Aryabhatta and Varahamihira, having accurately mapped the positions of celestial bodies, developed a method of computing a ship’s position from the stars. A crude forerunner of the modern magnetic compass called Matsyayantra was being used around the fourth or fifth century CE. Between the fifth and tenth centuries CE, the Vijayanagara and Kalinga kingdoms of southern and eastern India had established their rules over Malaya, Sumatra and Western Java. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands then served as an important midway for trade between the Indian peninsula and these kingdoms, as also with China. The daily revenue from the western regions in the period 844-848 CE was estimated to be 200 maunds (eight tons) of gold.

Not only was there trade from ancient times, going to many areas of the globe, but other countries may have also been going to India. It is reported that marine archaeologists have found a stone anchor in the Gulf of Khambhat with a design similar to the ones used by Chinese and Japanese ships in the 12th-14th century CE, giving the first offshore evidence indicating India’s trade relations with the two Asian countries. The stone anchor was found during an exploration headed by two marine archaeologists, A. S. Gaur and B. K. Bhatt, from the National Institute of Oceanography (NIO). Mr. Gaur stated

“Though there are a lot of references and Chinese pottery (found from coastal sites) indicating trade relations between the two Asian nations (China and Japan) in the past, but this anchor from the offshore region is the first evidence from Indian waters. Similar type of anchors have been found from Chinese and Japanese waters,” 2

Furthermore, another recent finding that shows the ancient advancement of Indian maritime capabilities is the evidence that Indian traders may have gone to South America long before Columbus discovered America. Investigation of botanical remains from an ancient site, Tokwa at the confluence of Belan and Adwa rivers, Mirzapur District, Uttar Pradesh (UP), has brought to light the agriculture-based subsistence economy during the Neolithic culture (3rd-2nd millennium BCE). They subsisted on various cereals, supplemented by leguminous seeds. Evidence of oil-yielding crops has been documented by recovery of seeds of Linum usitatissimum and Brassica juncea. Fortuitously, an important find among the botanical remains is the seeds of South American custard apple, regarded to have been introduced by the Portuguese in the 16th century. The remains of custard apple as fruit coat and seeds have also been recorded from other sites in the Indian archaeological context, during the Kushana Period (CE 100-300) in Punjab and Early Iron Age (1300-700 BCE) in UP. The factual remains of custard apple, along with other stray finds, favor a group of specialists to support with diverse arguments the reasoning of Asian-American contacts way before the discovery of America by Columbus in 1498. 3

The Indian navy and sea power

In the south especially there was an established navy in many coastal areas. The long coastline with many ports for trade for sending out ships and receiving traders from foreign countries necessitated a navy to protect the ships and ports from enemies. According to records, the Pallavas, Cholas, Pandyas, and the Cheras had large naval fleets of ocean bound ships because these rulers also led expeditions against other places, such as Malayasia, Bali, and Ceylon.

The decline of Indian maritime power commenced in the thirteenth century, and Indian sea power had almost disappeared when the Portuguese arrived in India. They later imposed a system of license for trade, and set upon all Asian vessels not holding permits from them.

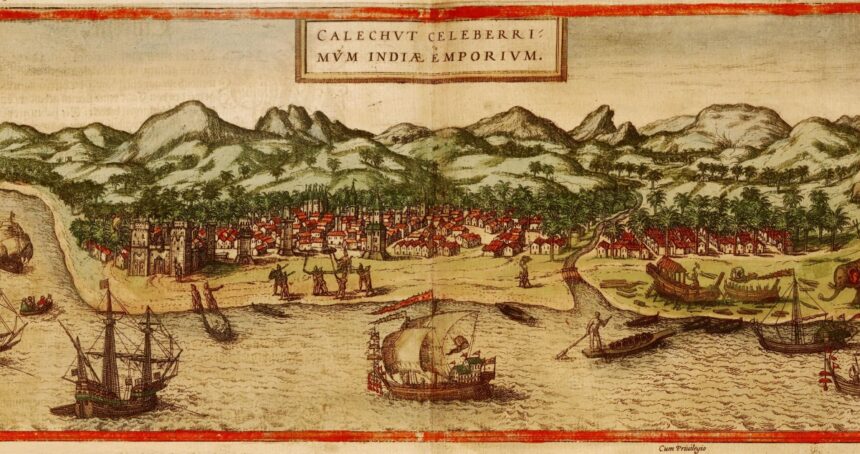

The piratical activities of the Portuguese were challenged by the Zamorins of Calicut when Vasco da Gama, after obtaining permission to trade, refused to pay the customs levy. Two major engagements were fought during this period. First, the battle of Cochin in 1503, clearly revealed the weakness of Indian navies and indicated to the Europeans an opportunity for building a naval empire. The second engagement off Diu in 1509 gave the Portuguese mastery over Indian seas and laid the foundation of European control over Indian waters for the next 400 years.

Indian maritime interests witnessed a remarkable resurgence in the late seventeenth century, when the Siddhis of Janjira allied with the Moghuls to become a major power on the West Coast. This led the Maratha King Shivaji to create his own fleet, which was commanded by able admirals like Sidhoji Gujar and Kanhoji Angre. The Maratha Fleet along with the legendary Kanhoji Angre held sway over the entire Konkan Coast keeping the English, Dutch and Portuguese at bay. The death of Angre in 1729 left a vacuum and resulted in the decline of Maratha sea power. Despite the eclipse of Indian kingdoms with the advent of western domination, Indian shipbuilders continued to hold their own well into the nineteenth century. The Bombay Dock completed in July 1735 is in use even today. Ships displacing 800 to 1000 tons were built of teak at Daman and were superior to their British counterparts both in design and durability. This so agitated British shipbuilders on the River Thames that they protested against the use of Indian built ships to carry trade from England. Consequently, active measures were adopted to cripple the Indian shipbuilding industries. Nevertheless, many Indian ships were inducted into the Royal Navy, such as HMS Hindostan in 1795, the frigate Cornwallis in 1800, HMS Camel in 1801, and HMS Ceylon in 1808. HMS Asia carried the flag of Admiral Codrington at the battle of Navarino in 1827, the last major sea battle to be fought entirely under sail.

Two Indian built ships witnessed history in the making. The Treaty of Nanking, ceding Hong Kong to the British, was signed onboard HMS Cornwallis in 1842. The “Star Spangled Banner” national anthem of the USA was composed by Francis Scott Key onboard HMS Minden when the ship was on a visit to Baltimore. Numerous other ships were also constructed, the most famous being HMS Trincomalee, which was launched on 19 October, 1817, carrying 86 guns and displacing 1065 tons. This ship was latter renamed Foudroyant.

The period of 4000 years between Lothal and Bombay Dock, therefore, offers tangible evidence of seafaring skills the nation possessed in the days of sail. In the early seventeenth century, when British naval ships came to India, they discovered the existence of considerable shipbuilding and repair skills, as well as seafaring people. An ideal combination was thus available for supporting a fighting force in India. 4

How the British killed the maritime industry in India

When the westerners made contact with India, they were amazed to see their ships. Until the 17th century, European ships were a maximum of 600 tonnes. But in India, they saw such big ships as the Gogha, which was more than 1500 tonnes. The European companies started using these ships and opened many new factories to make Indian artisans manufacture ships. In 1811, Lt. Walker writes, “The ships in the British fleet had to be repaired every 12thyear. But the Indian ships made of teak would function for more than 50 years without any repair.” The East India Company had a ship called Dariya Daulat which worked for 87 years without any repairs. Durable woods like rosewood, sal and teak were used for this purpose.

British East India Company ships at dock in Calcutta.

The French traveler Waltzer Salvins writes in his book Le Hindu, in 1811,

“Hindus were in the forefront of ship-building and even today they can teach a lesson or two to the Europeans. The British, who were very apt at learning the arts, learnt a lot of things about ship building from the Hindus. There is a very good blend of beauty and utility in Indian ships and they are examples of Indian handicrafts and their patience.”

Between 1736 and 1863, 300 ships were built at factories in Mumbai. Many of them were included in the Royal Fleet. Of these, the ship called Asia was 2289 tonnes and had 84 cannons. Ship building factories were set up in Hoogly, Sihat, Chittagong, Dacca, etc. In the period between 1781 to 1821, in Hoogly alone 272 ships were manufactured which together weighed 122,693 tonnes.

In this connection, Suresh Soni, in his book India’s Glorious Scientific Tradition, explains how India was deprived of its marine industry, but also from any notation in its ancient history of its ship-building ability. He writes:

“The shipping magnates of Britain could not tolerate the Indian art of ship manufacturing and they started compelling the East India Company not to use Indian ships. Investigations were frequently carried out in this regard. In 1811, Col. Walker gave statistics to prove that it was much cheaper to make Indian ships and that they were very sturdy. If only Indian ships were included in the British fleet, it would lead to great savings. This pinched the British shipbuilders and the traders.”

Dr. Taylor writes,

‘When the Indian ships laden with Indian goods reached the port of London, it created such a panic amongst the British traders as would not have been created, had they seen the enemy fleet of ships on the River Thames, ready for attack.’

“The workers at the London Port were among the first to make hue and cry and said that ‘all our work will be ruined and families will starve to death.’The Board of Directors of East India Company wrote that ‘all the fear and respect that the Indian seamen had towards European behavior was lost when they saw our social life once they came here. When they return to their country, they will propagate bad things about us amongst the Asians and we will lose our superiority and the effect will be harmful.’ At this, the British Parliament set up a committee under the chairmanship of Sir Robert Peel.

“Despite disagreement amongst the members of the committee on the basis of this report, a law was passed in 1814 according to which the Indians lost the right to become British sailors and it became compulsory to employ at least three-fourth British sailors on British ships. No ship which did not have a British master was allowed to enter London Port and a rule was made that only ships made by the British in England could bring goods to England. For many reasons, there was laxity in enforcing these rules, but from 1863 they were observed strictly. Such rules which would end the ancient art of ship-building, were formulated in India also. Tax on goods brought in Indian ships was raised and efforts were made to isolate them from trade. Sir William Digby has rightly written, ‘This way, the Queen of the western world killed the Queen of the eastern oceans.’ In short, this is the story about the destruction of the Indian art of ship-building.” 5

Of course, let us not forget that not only was commerce between ancient India and other countries made through maritime capabilities, but also through land routes that extended to China, Turkistan, Persia, Babylon, and also to Egypt, Greece, and Rome, which continued to prosper.

These days, India is still very much in the ship building business, mostly in small and medium size ships. As of 2009 there were 27 major shipyards, primarily in Mumbai, Goa, Vishakhapatnam, and Cochin.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the fact is that the ancient Vedic civilization had a strong connection with the sea, and maritime abilities. Even in their language of Vedic Sanskrit, words such as samudra, salil, sagar, and sindhu indicated the sea or large rivers. The word sindhuka also meant sailor, which became the name Sindbad for the sailor in Arabian Nights. Also, the English word navigation actually originates from the Sanskrit word Navagati.

Further evidence has been shown, such as that presented at a 1994 conference on seafaring in Delhi where papers had been presented that shows how Indian cotton was exported to South and Central America back in 2500 BCE. Another report suggested Indian cotton reached Mexico as far back as 4000 BCE, back to the Rig Vedic period. According to Sean McGrail, a marine archeologist at Oxford University, seagoing ships called ‘clinkers’ that were thought to be of Viking origin, were known in India a good deal earlier. Thus, India’s maritime trade actually flourished many years ago, along with many other of its advancements that are hardly recognized or accounted for today. 6

This helps reveal that India’s maritime trade actually flourished more and far earlier than most people realize. This was one of the ways Vedic culture had spread to so many areas around the world. Though the talents and capabilities that came out of ancient India’s Vedic civilization have often remained unrecognized or even demeaned when discussed, nonetheless, the Vedic people were far more advanced in culture and developments then many people seem to care to admit, and it is time to recognize it for what it was.

References / Footnotes

1. Kapur, Kamlesh, Portraits of a Nation: History of India, Sterling Publishers, Private Limited, 2010, pp. 414-15.

2. http://www.hindu.com/thehindu/holnus/000200903151560.htm.

3. http://www.ias. ac.in/currsci/ jan252008/ 248.pdf.

4. http://indiannavy.nic.in/maritime_history.htm.

5. Soni, Suresh, India’s Glorious Scientific Tradition, Ocean Books Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, 2010, p. 74-75.

6. Frawley, Dr. David, and Dr. Navaratna S. Rajaram, Hidden Horizons, Unearthing 10,000 Years of Indian Culture, Swaminarayan Aksharpith, Ahmedabad, India, 2006, p. 79.

Leave a Reply