This essay was published under the title Bhāgīrathīr Utsa Sandhāne in the April 1895 issue of the journal Dāsī, edited by Ramananda Chattopadhyaya. It is known from his private diaries that in 1893 Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose visited Almora. This essay was the first composition that announced his name in the world of literature and made him known as a man of letters.

*******

Not far below my house flows the mighty Ganga. Right from the days of my childhood, I have felt a deep friendship with the river. One season in the year, the river would overflow its banks and assume an extensive form, stretching far and wide. Then at the end of winter, the river would assume a shriveled and shrunken form. Every day I noticed the change in the flow, as the tide rose and ebbed. The river appeared to be a living entity subject to change of form and pace. At dusk, I used to come to the bank of the river alone, and sit by its side. I could hear the incessant kulu-kulu sound made by the tiny wavelets crashing into the shore, breaking, and flowing back into the river. As it grew darker, and the noises of the external world gradually fell silent, I could listen very closely to these gurgling sounds. Sometimes I marveled that this immeasurably great current of water that flows away every day never comes back. Where then does this inexhaustible current come from? Does it really have no end? I would ask the river: “Where do you come from?” The river would answer: “From the locks of Mahādeva!” And then the story of Bhagiratha bringing down the Ganga would flash into my memory.

Later, when I grew up, I heard many explanations regarding the river’s birth. However, whenever I would sit down by the river, in a tired state of mind, I would again hear the same words among the ever-familiar gurgling sounds: “From the locks of Mahādeva!”

One day I witnessed the mortal remains of a dear one being reduced to ashes in a funeral pyre on the banks of the river. This person had been very close to me all my life, and the temple of motherly affection suddenly seemed vacant. To which unknown and unknowable place had the deep, wide current of that love flowed? One who passes away does not return: has he then disappeared for all time? Is death really the end of life? Where does one who passes away go? Where is my dear one now?

In the gurgling of the river, I heard the words: “At the feet of Mahādeva!” It had grown dark. In between the kulu-kulu sound, I heard the words: “We go back to where we came from! After a long course, we go to merge in the source”.

I asked: “Where do you come from, Nadī?” The river replied with the same old words: “From the locks of Mahādeva!”

One day I said to the river: “Nadī, you and I have been friends for a long time now. In the old days, it was only you! From my childhood up until the present, my life has been wrapped up in you! You have become a part of my life. Where you come from, I do not know! I will follow your course, and I will find your source!”

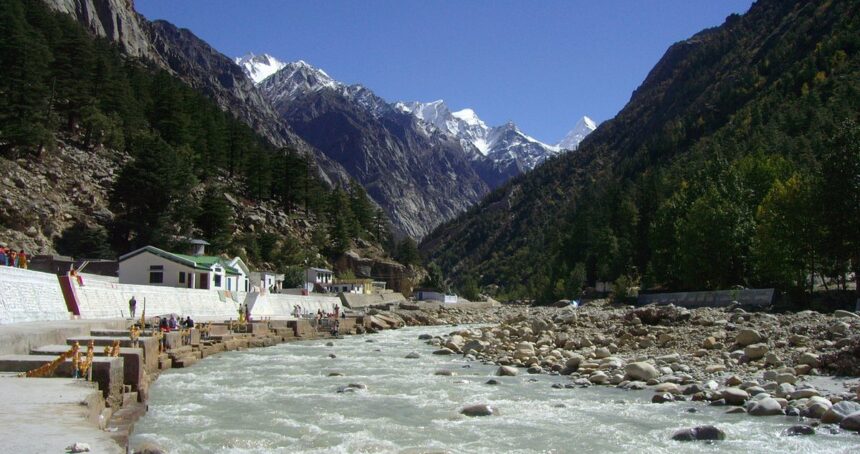

I had heard that the Jāhnavī is born somewhere in the snow-laden mountains that are visible in the north-west. With these peaks as my destination, I set off in my quest through villages, provinces, and desolate lands. My journey took me to the Kurmāchala country, celebrated in the Purāṇas. I visited the source of the Sarayu, and arrived in Dānavapur. Then, resuming my journey again, I began my northward trek, through forests and over mountains.

One day, while I was walking a particularly difficult and tortuous mountain path, I set myself down, overpowered by fatigue. I was surrounded by mountains on all four sides, with dense forests behind them. A cloud-piercing peak stood right in front of me barring the view of the background with its sheer size. My guide explained: “You will achieve your heart’s desire once you climb this peak. The silver thread that you can see down in the distance, winds its way through many lands before entering your country in its powerful, rapidly-flowing and extensive form, overflowing its banks. As soon as you get to the summit in front of you, you will see where the slender thread emerges from!

On hearing these words, I forgot all my weariness and began to climb the mountain with renewed vigour.

Suddenly my guide drew my attention to the sights ahead, and exclaimed: “Jai Nandā Devī! Jai Triśūl!”

A few moments ago the mountain-range had been blocking my view. But just as soon as I reached a summit, the veil was lifted from my eyes, and I saw an infinite expanse of blue sky. Piercing this blue canopy were two massive snowy forms, which rose up straight into the heavens. Like a tall and beautiful woman! I had the feeling they were both looking at me calmly and affectionately. I recognized one of them, Nandā Devī, as the symbol of the Mother that is the Earth, in whose wide lap many forms of life find shelter and sustenance. Close to Nandā Devī stood the Triśūl, which rose from the depths of the nether-world, penetrated the earth, and with its sharpened blade pierced the celestial canopy – lynch-pin of the three worlds that are strung around it.

Thus, in close proximity to each other, I had darśan of the symbol of manifested creation and the instrument of the creator. I then understood that the Triśūl was the symbol of stasis and of dissolution.

My guide said: “We still have a long way ahead of us. It is going to be an arduous trek. After two days’ walk, we will catch a glimpse of the glacier.”

After surmounting the wooded and mountainous obstacles that presented themselves to us in the next two days, I was finally ushered into the land of snow. The silvery thread of the river that had been visible to me in the distance had grown ever more slender. Even the current that had resounded gently in my ears for so long had suddenly fallen silent. The liquid waters had turned into hard immovable frost. I looked around and saw that in many places, giant trains of waves had been petrified, as though the playful, rippling waves had been rendered motionless by a spell: Tiṣṭha! Who is the great artist, who had gathered all the crystals in the world, to create this massive sculpture of a stormy sea?

On two sides stood ranges of the tallest mountains. Stretching from their foothills to the high precipices was a thick forest consisting of countless tall trees shedding flowers continuously. Streams starting as trickles from the snowy summits snaked their tortuous course into the valley down below. Nandā Devī and Triśūl were no longer clearly visible: a dense fog cast a veil and barred the view.

I resumed my ascent walking on the glacier, which springs from the highest peak of the Dhavalagiri mountain. In its course, it cleaves the mountains as it transports rocks and boulders, which are scattered here and there. I had to climb from one treacherous boulder to another. As the altitude increased, the atmosphere became progressively rarer. The thin air was laden with pollen from the Deva-dhūpa trees. Gradually my breathing grew more laboured, and my body wearier. Finall,y I fell down almost unconscious at the foot of Nandā Devī.

All of a sudden, the sound of a hundred conch-shells penetrated my ears. Though eyes half-open I saw that a great pūjā was being conducted in the entire mountain and forest country. Waterfalls issued as if out of so many great kamanḍalus. In coordination with them, the pārijāta-trees voluntarily offered their flowers for worship. In the distance a deep sound resembling that of a conch-shell shook the very horizons. Whether it was the sound of a conch or thunder reverberating in the icy mountains, I could not distinguish.

A little later, my heart felt the excitement, and my body trembled with the thrill of the sight that lay before me. The fog that had hidden the view of Nandā Devī and Triśūl was being cleared, and the veil gradually vanished. A great glow illuminated the top of Nandā Devī, which was itself barely noticeable. But the vapours that emanated from the effulgence in the form of wisps spread far and wide. Were these fibrous strands the locks of Mahādeva? These locks that had surrounded Nandā Devī, emblem of Mother Earth, as if in gentle moonlight! These locks of Mahādeva which have placed on the head of the goddess Nandā Devī a diadem of diamond-like snow-flakes – flakes chipping off Triśūlʼs blade!

Shiva and Rudra! Preserver and Transmuter! Now their meaning was clear! In the mindʼs eye I had been able to see drops of water setting out in quest of the sea, and from the sea making the return journey to the source. At this source, powered by the great cycle, I saw the twin processes of creation and dissolution side by side.

Drops of water assuming the form of snow, penetrate deep into the sky-piercing mountains that were ranged in front of me. After strenuous efforts, the snow eventually succeeds in splitting the bodies of the mountains. The broken summits fall into the valley below, to the accompaniment of thunderclaps. The falling debris is gathered down below on a bed of snow created by water droplets. The droplets seem to confer among themselves, saying “Come, let us take the bones of these boulders and refashion a new earth.”

These droplets which are like numberless atomic units of power – millions upon millions of tiny hands – combine to make light work of transporting mountain-loads of rock. Where no path exists before, the friction of the rocks themselves carves out a way, and valleys come into existence. By constantly scraping against the mountain-sides, the heaps of rock finally turn into rubble.

On both sides of what was my camping-site, piles of glacier-borne rock are lying around. Just a little downhill, particles of snow have assumed liquid form, and have given birth to a tiny stream. This stream winds its course through the highlands bearing the skeletal remains of the mountains, flowing past prosperous cities through many a populous province, and makes its way to the sea. Along the journey, the river finds that in some places, the land on both banks is practically a desert. The river overflows its banks, and its mineral-laden waters render the soil fertile. From the hard and inanimate rock are born lush plants, tall trees and delicate creepers, throbbing with life.

Particles of water assume the form of rain, and bathe and cleanse the earth, carrying dead and rejected matter into the sea. There in the depths, hidden from the sight of man, new realms are created. Even after merging with the sea, drops of water remain agitated, and continue to erode the coastland, as they are buffeted around by the waves. Sometimes particles of water penetrate deep into the earth, and become āhutis in the altar-fires of Pātāla. Vapours rising from the great yajñas rend the earth and manifest themselves in the eruptions of volcanoes, whose great energies cause the earth to quake. High ground sinks low, and the seabed rises to form new lands.

Even after merging in the sea, there is no respite for the swarms of water-drops. Heated in the fires of the Sun, they evaporate, rise and become airborne. Then, racing up to the summits of mountains, they manifest themselves in the form of storms and thunder. They find shelter in the profuse misty mountain-locks. In the course of time, when their period of rest is over, they condense into snow on the mountain-tops. This cycle continues ceaselessly without respite.

Even now I often sit on the banks of the Bhāgirathī, and lend my ear to the kulu-kulu song. Even now I hear the words of the song, as I did before. Now there is neither error nor doubt in my understanding.

“Nadī, where do you come from?”

I hear the reply clearly: “From the locks of Mahādeva!”

*******Translator’s Dedication: I dedicate this translation to the memory of my dear departed mother, Vijayalakshmi, who embarked on a journey to seek the feet of Mahādeva six years ago. I am grateful to the many friends and family members whose heartfelt goodwill and support consoled me at that time. I will name only a few: my mother’s friend Mrs. Uma Mehta; my brother Maheshchandra; aunt Radha, uncle Shankar and their son my cousin Mahesh; my friends Vandana and Rajaram, and Aditya, Aruna andPrashanth. They confirmed the truth of the dictum:rājadvāre smaśāne ca yastiṣṭhati sa bāndhavah!

Image Source: Atarax42 – {https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5336169}

Leave a Reply