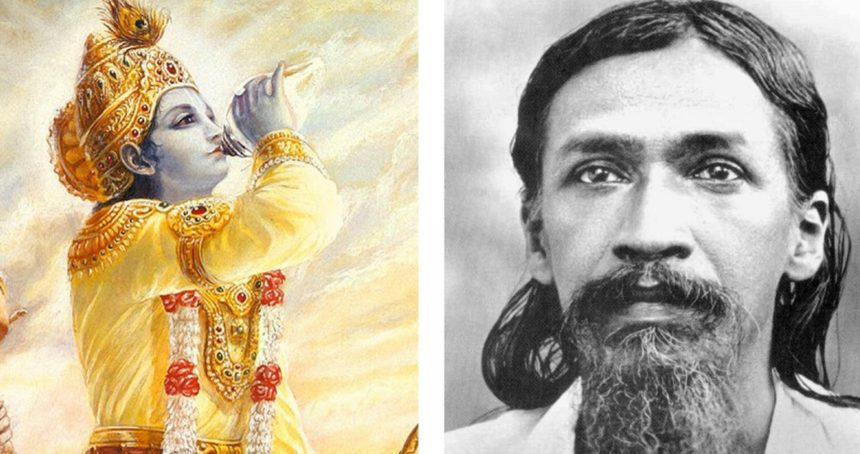

Krishna’s eternal message in the Bhagavadgita is the civilizational vision of India that inspired its freedom struggle and found a new expression in the writings of Sri Aurobindo.

Freedom, Krishna and Sri Aurobindo: The Civilisational Vision of India

August 15, 2017, which commemorated India’s seventieth year as an independent nation was indeed a momentous occasion. Days like these do not come often. It also happened to be Krishna Janmashtami (for the Vaishnavas) and the day when Sri Aurobindo, a revolutionary freedom fighter and Rishi, was born. For those who see India as a civilisation and not merely a recently formed nation-state, there are deeper connections that bind these three occasions.

Krishna Janmashtami, believed to be the day the divine descended in the form of Sri Krishna holds special significance across India. While many cherish and celebrate Krishna as the irresistible prankster and eternal lover, many others seek inspiration in the perfect yogi and the visionary statesman, the Krishna of the Bhagavad Gita who, as Swami Chinmayananda said, “brought the Vedic truths from the sequestered Himalayan caves into the active fields of political life”. Even a cursory look at the life of Krishna reveals that he did not shy away from action, but actively involved himself in statecraft and the political and social turmoil of his time with a clear vision of re-establishing Dharma. Dharmakshetre Kurukshetre, in the field of Dharma and the field of the Kurus, he gave the clarion call of the Bhagavad Gita which propounds an integral unity and dynamic synthesis of the material and spiritual, action and stillness and how to face the turbulence of life while responding to the call of Desha and Dharma. Through millennia, Krishna’s vision as expounded in the Bhagavad Gita has been a source of inspiration, the bedrock upon which many great Acharyas have built their Darshanas. Along with the major Upanishads and the Brahmasutras of Vyasa, Krishna’s Gita is one of the Prasthana Trayi, the three axiomatic texts considered authoritative and commented upon by many Sampradayas, or schools of thought. During the freedom struggle, thousands found their inspiration in the Gita.

Whenever a nationalist was arrested in the 1900s, inevitably the police would find a copy of the Gita in his possession. So frequently did this happen that the British Government at one point considered banning the book for inflaming seditious thoughts. There are recorded instances of many who went to the gallows with the Gita in their hands. On one hand, the Gita inspired Lokamanya Tilak’s political philosophy including his clarion call for Swaraj, evident from the fact that the most systematic exposition of his political thought was ‘Gita Rahasya’, a commentary on the Gita. On the other end of the spectrum, Gandhi too sought his inspiration in the Gita, though how he interpreted the Gita as a pacifist doctrine eludes many.

Krishna and his Bhagavad Gita were a deep source of inspiration for Sri Aurobindo, both in his political as well as spiritual journey. Sri Aurobindo today is largely remembered as a “philosopher” and finds a one line mention in history books as an extremist leader. He was much more than that – a revolutionary freedom fighter, a poet, a philosopher, a classical scholar, a literary critic, and a yogi and visionary who gave a roadmap for the rise of India and the spiritual evolution of mankind. From someone who received an entirely European upbringing, he became one of the leading lights of the freedom struggle in the early 1900s, travelling across Bengal creating revolutionary groups and working with Tilak and Sister Nivedita. As a leader of the Nationalist faction of the Indian National Congress, he boldly called for a program of Purna Swaraj (complete independence) at a time when many were petitioning for greater representation or home rule. Through his writings in the Karma Yogin and Bande Mataram, he gave a civilisational vision of India and elevated the freedom struggle to the realm of the spiritual, inspiring a whole generation in Bengal. After his retirement to Pondicherry, he wrote on the rise of India, her civilisational genius and his vision for human evolution. In his vast vision, there was no scope for conflict between the national and the universal.

“She(India) does not rise as other countries do, for self or when she is strong, to trample on the weak. She is rising to shed the eternal light entrusted to her over the world. India has always existed for humanity and not for herself and it is for humanity and not for herself that she must be great.”

Sri Aurobindo was clear that India had to rise not by destroying her moorings and beginning afresh but through rediscovering her civilisational genius and approaching our problems in the light of the Indian spirit.

“The recovery of the old spiritual knowledge and experience in all its splendour, depth, fullness is its first, most essential work; the flowing of this spirituality into new forms of philosophy, literature, art, science and critical knowledge is the second; an original dealing with modern problems in the light of Indian spirit and the endeavour to formulate a greater synthesis of a spiritualised society is the third and most difficult. Its success on these three lines will be the measure of [India’s] help to the future of humanity”.

On the day India attained Independence, he spoke about his vision for India and the world. His first dream was a revolutionary movement that would ensure a united and free India. While this was marred by Partition, he hoped for a future unification in some form. His second dream was the rise of Asia and her people for the progress of humanity. The third dream was for the unification of mankind and the world. The fourth dream was the spiritual gift of India to the world. The final dream was the evolution of man to a higher consciousness. Seventy years later, the rise of Asia and the spiritual gift of India to the world are becoming a reality.

The seventieth year of Independent India is a momentous occasion. While this is indeed a time for us to celebrate, it is also a time for us to reflect on what is the idea of India that we celebrate, what it means to be Indian and what is the vision for India and her role in the world. In grappling with these fundamental questions, artificial dichotomies of ancient and contemporary, past and present break down. Krishna’s message was a foundational inspiration for a freedom struggle that took place thousands of years later. Similarly, Sri Aurobindo gives us an integral vision of India’s rise, her role in the world and the future evolution of mankind. Sri Krishna and Sri Aurobindo are highly relevant to our today and our tomorrow. They “do not belong to the past dawns but to the noons of the future”. The vision of the thousands of great beings who have lived in our land must flow into our social, political, economic and cultural life. India as a civilisation must inform India as a nation.

Leave a Reply