This article is an attempt to understand ‘caste’ based on the writings of several Christian missionaries that worked in India during the early 19th and 20th centuries and documented their experiences. The aim is to serve as a reflection to contextualise ‘caste’ citing excerpts that adequately illustrate its role in society then and offer some nuance, in a world dominated by sweeping and often flawed generalisations and passionate denouncements.

Before we delve further into the specific observations and approach of missionaries, it is important to clarify some broad thoughts on this contentious topic and the reasons for the pertinence of this discussion in these times. For this, it is apt to reflect on the words of the anthropologist/sociologist A.M.Hocart on this subject, which have also been quoted by the traditionalist scholar A.K.Coomaraswamy multiple times in his work.

Hereditary service has been painted in such dark colors only because it is incompatible with the existing industrial system” (Les castes, p. 238)

A large part of the pre-industrial world operated through ancestral professions and hereditary occupations until the conception of enlightenment ideals and efforts such as those of Napoleon Bonaparte to mainstream the idea of “careers open to talents”. This pre-enlightenment division of the workforce based on hereditary services was far more structured and integrated into society in India than it was elsewhere in the world, through caste.

There have been notable exceptions to the hereditary “norm” throughout history, along with the occasional instances of mobility or flexibility or even the creation of new castes. But typically, most followed their ancestral professions and religious customs and it is through this efficient system they not only passed on highly specialised knowledge to their progeny but also attempted to reconcile their station in life. The purpose here is not to deliver a moral judgement on caste – besides, this model of economic division may seem incompatible with current free-market/capitalist systems – but to gain insight into our society by intelligibly reflecting on the past. It was what it was (and still is). This is how our world operated, and thrived prior to the advent of the British.

As A.M.Hocart mentioned in Les Castes, it is acceptable, and easy enough to assert that hereditary service is incompatible with our “modern” lives in a post-industrial revolution world, and therefore imperative that we pursue the linear path of “progress”. However, there is a glaring uncertainty regarding the manner and the time period in which India is proposed to become the “casteless” egalitarian utopia that social reformers dreamt of, and the form Hinduism would adapt to when faced with such an eventuality.

The debate surrounding a possible census-taking caste into account is currently raging. Caste continues to be ascribed to citizens by birth by the constitutional/judicial/state machinery and by politicians in order to perpetuate caste-based welfare schemes, affirmative action and vote bank consolidation. Despite the efforts and incentives offered by multiple governments, caste endogamy persists by the power of custom. Even outside this situation, progeny continue to embrace caste identity (and state benefits) patrilineally.

The damage done when the economic backbone of this interdependent system was broken has had lasting effects. Hindus today continue to live in a state of confusion, primarily because, as observed by the missionaries, caste is inextricably linked with not only traditional occupations and a certain ‘way of life’ but crucially with religiosity and familial/local customs and traditions – so much so that most Hindu communities have no clue (nor inclination in most cases) to separate the two.

An effective mechanism by which caste can be practically annihilated has not been worked out as yet, caste continues to be alive and kicking despite the lack of strict enforcement of hereditary professional succession. To make matters worse, there is an increasing critique emerging in economies worldwide that inequality is only increasing, with meritocracy seeming to legitimize or justify those massive inequalities rather than eliminating them. Consequently, the alternatives before us for the hypothetical utopia following the eradication of caste are neither clear nor particularly alluring.

A machine civilization is decidedly against hereditary succession in professions. It is widely acknowledged in popular discourse that though technology has a tendency to continuously disrupt livelihoods, it is in our best interests to adapt. As a result, there is perhaps no point in harping on about hereditary succession as far as the economic sphere is concerned, in which growth is mostly technology-driven now, with little in the control of communities or guilds – and this situation is predicted to persist, at least until the near future. Therefore, this article is not so much about the economic or livelihood aspect of hereditary succession but focused on its religious and cultural impact. It is about taking a step back and recognising the tragic loss of cultural memories, identities and the entirety of inheritance of a people, which is the natural consequence of the relentless pursuit of “castelessness” compounded by the marginalization of hereditary succession.

A lot of public intellectuals today don’t seem to understand the extent of the importance of caste-based traditions to practising Hindus in India, especially prior to the advent of colonial “modernity”. Hence, the corollary is that the Hindu intellectual class is unable to formulate a blueprint for the life and religious consciousness of a hypothetical “casteless Hindu”, at least not one convincingly rooted in and respectful of Hindu knowledge systems. Since most practising Hindus commonly rely on caste to connect with their religion, caste continues to persist as far as rituals, customs, festivals and traditions go, apart from enduring as a vital source of kinship and community for many. Our society remains suspended in a transitional phase, attempting to negotiate tradition with industrial modernity.

Sociologist M. N. Srinivas explained this best in his 1962 article published in EPW titled “Changing Institutions and Values in Modern India”:

“Social institutions and values are undergoing change in India. This will affect everyone and especially the Hindus, as Hinduism is dependent for its perpetuation on institutions which are changing in important ways. This ought to be a matter for concern because it is necessary to provide the younger generation with a sense of purpose and of values. Nationalism may provide the former for the people, but it will not provide the latter. Even internationalism will not be enough. What will be necessary is a personal philosophy of life, a Weltenschaaung. Where is this to come from ? If the bulk of the people derive their Weltenschaaung from their religion, and if this religion is very largely dependent upon a triad of social institutions viz caste, joint family and village community, which are changing in important respects, what will be the consequences for the people concerned and their country. I am afraid I do not have an answer, but what worries me even more is that there is not widespread awareness of the existence of this problem.”

M.N. Srinivas also considers what the fate of Hinduism would be if caste were to disappear:

There is one question which, though extremely important, I have refused to consider, and that is, “What will happen to Hinduism when caste disappears?” It raises such far-reaching issues that I cannot hope to deal with it satisfactorily here”

Hinduism without birth-based caste is a conundrum and difficult to conceive. If it were so simple, perhaps someone like Dr. Ambedkar would have suggested it decades ago, rather than advocate for conversion to Buddhism. Hindu intellectuals who champion the complete elimination of birth based caste, including in the religious sphere, ostensibly lack a clear understanding of the far-reaching deleterious effects this change might have on Hinduism.

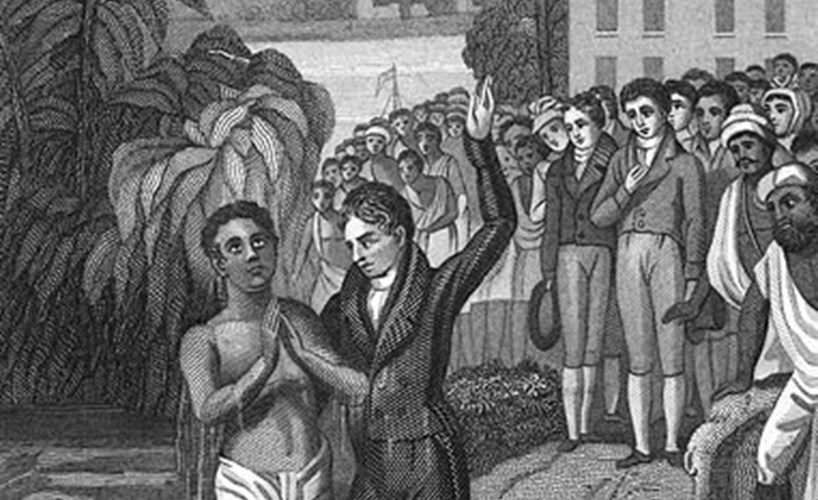

To illustrate the centrality of caste to Hindus, we shall turn our attention to the writings of Christian missionaries who spent time in India between 1800–1950, from which we can note their observations and draw a few pertinent conclusions. Since the experiences and opinions of Hindu religious leaders and scholars are often dismissed without consideration by fellow Hindus themselves, who better to be informed by than the very set of individuals that sought (and still seek – through neo-colonial organisations such as Christian missions and some NGOs) to destroy Hindu societal structures to aid their evangelical pursuits?

Below are selected quotes from missionary literature circulated about Hindus, caste and India. Their colonial gaze did indeed fall short in the understanding of some aspects of Hinduism, Hindu society and history (a fact well-documented by many researchers/academics). However, the purpose of this article is to throw light on the missionary understanding of caste serving as a principal tenet of the practice of the Hindu religion and therefore a strong, sturdy “opponent” or “barrier” to successful conversion and subsequent loyalty to Christianity.

This excerpt below is from the book “Missions to Hindus: A contribution to the Study of Missionary Methods” (published 1908) written by the former Bishop of Bombay, Louis George Mylne:

“Caste looked at simply in itself, in isolation from its proper surroundings, is essentially a social system. All the same, it constitutes the religion, for every practical purpose, of hundreds of millions of people. And it moulds their personal characters to an absolutely incalculable extent. It stands as the link of connection between religion and personal character; between the religious beliefs which gave it birth and the character which, in its turn, it has produced. It accounts for the Hindu character; it is accounted for by the Hindu religion.

It forms the key to the entire position which missionary effort has to storm; for it is that which has riveted their religion as a chain upon the necks of the people; it is what renders the renunciation of Hinduism and the practical acceptance of Christianity an effort more exacting and more acute than aught which could ever, as I believe, be required of any of ourselves.

…Caste stands forth as the deadliest of all the opponents which the Gospel has to grapple within India.”

As evidenced above, missionaries understood clearly how so much in the life of a practising Hindu, including his morality, obligations, and sense of community belonging revolved(s) around caste, contrasted with the Christian theological notions of individualism. The Clergy and missionaries viewed caste as an impediment to their conversion project. This perspective is lost on many, especially those who parrot the same agenda-driven colonial critiques of caste to ironically, make a case against it. Some even take it upon themselves to carry a torch for the Christian missionary cause and squarely blame caste as the root of all problems faced by Hindu society. An alarmingly large section are under the erroneous impression that the elimination of caste will strengthen the Hindu political cause, despite evidence of the contrary – the fortitudinous nature of caste:

…the gigantic influence of heredity and age-long tradition, which, vast as it must be in any country, holds a place in the Indian equation unsurpassed, it may be unequalled.”

Here is another quote that aptly encapsulates the enormity of the opposition caste posed to early Christian missionaries:

Caste, in its every manifestation, is to be treated from the first, in all Missions, as the deadly antagonist of the Gospel, with which league or truce is impossible. Root-and-branch extermination is the only measure to be dealt to it.

It is fascinating to note that missionaries called for the “root-and-branch extermination” of caste a few decades before our own reformers invariably followed in their footsteps.

In another document compiled by Reverend I. H. Hacker describing the work of the London Missionary Society in Travancore, titled ”A hundred years in Travancore, 1806–1906: A History and Description of the Work Done by the London Missionary Society in Travancore, South India during the past century”, the following lines demonstrate yet again the manner in which caste was seen as a hindrance to mass conversion.

No doubt this caste exclusiveness is the reason to a large extent why missionary zeal is not a note of the Syrian Church, and for all its fifteen hundred years of existence, it has not crossed the borders of this little country and gone abroad to evangelize India.

This excerpt below is from ”India and Christian Missions” written by Reverend Edward Storrow of the London Missionary Society of Calcutta in 1859, describing the cruciality of Hinduism to the ethos of the nation itself, and how conversion was viewed as an act of betrayal:

It (Hinduism) is inextricably intertwined with the history of the race professing it; it breathes through all their national life; it forms the essence of all their philosophy and literature; it is associated with every act of life, from childhood to the grave. The hold it thus has upon an intensely conservative people may be imagined, and to abandon it seems to them an act of denationalization.

Abandoning Hinduism being seen as an act of denationalization in that era seems such a far cry from the times we now inhabit. The typical reaction of a Hindu to proselytisation seems to have changed drastically as well:

Yes, what you say is very right; your religion is true, and so is ours; yours is good for Englishmen, and ours is good for Hindus is a common remark to missionaries.

The above statement can be hailed as a symbol of tolerance of the “other” and continues to be a sentiment that resonates with most of Hindu society even today. However, the notion of “yours” and “ours” that is distinguished with so much clarity in the excerpt above is a nuance that is lost on many in favour of “inclusion” or even the more fanciful “secularism”, to their own detriment.

Missionary reports of that era more often than not depict a state of helplessness in failing to convert natives and meet their ‘targets’ despite their best efforts. The notion of ‘target’ here is not meant to be derogatory – missionary literature carries elaborate tabulations and statistics on the “progress” of conversions relative to those the Gospel had “not yet reached”, in order to raise funding for future undertakings back home. Infamous initiatives like the Joshua Project documents conversion objectives in meticulous detail to this day.

Another interesting remark from the same book by Reverend Edward Storrow, in a section titled “The Obstacles”, is accusatory of the Hindu belief of caste being a “binding law” over the morality professed in the śāstras:

In the Shastras, there are good moral lessons and long drawn ethical speculations but they are not an essential part of Hinduism. Its requirements are social and ceremonial only. To keep caste is the one law binding on a Hindu.

Caste, in the opinion of the Hindu, involves distinctions not only of a secular and social kind but also of a religious nature, and these distinctions are not accidental, arbitrary, and temporary, but immutable, fundamental, and divine.

[The above comment on caste and śāstras is also echoed by Dr. Ambedkar in some of his writings on caste (particularly “Annihilation of caste”)].

On the impact of losing one’s caste by converting to Christianity – a stance quite contrary to the Indian state’s considerations on conversion :

To become a Christian is to lose caste, to lose sanctity, honour, purity, and indeed all that is precious; and it is to become vile, despicable and impure as well. Need we say how the Hindu turns away with loathing from the very thought!

Rev. Storrow brings our attention to a crucial and strategic property inheritance law passed in 1850 while under Company rule called the Caste Disabilities Removal Act, 1850, wherein he observes that prior to the passing of this Act, the ex-communication of a convert from their caste/religion was a major deterrent to conversion to Christianity as it meant that they could not inherit ancestral wealth or property from their family.

Until 1850 the Hindu who abandoned his ancestral faith could not inherit property; now, thanks to the justice of the British Government, the Hindu Christian has a claim equal to that of his idolatrous brother. But though the law makes no distinction, society does. He who breaks caste is never permitted to live with his family, or to eat with them. The circle in which he formerly moved avoid him as Jews would a leper, and all the associations in which a Hindu takes such pleasure — intermarriage, concourse with equals, and status in society — are his no more. All the ignominy, pollution, and disgrace associated in the minds of the most bigoted and superstitious with the ideas of outlaw, ostracism, ex-communication, and foul disease, are heaped upon his head. Even when Christian faith enables a man to surmount that intense prejudice, fear, and loathing with which he has habitually regarded the loss of caste, the relative obstacles thrown in his way are of the most formidable nature. Every friend he has will regard his act with a singular degree of grief and abhorrence, paralleled by no emotions which an Englishman can call forth amongst his relatives by any act of folly or of a crime he might commit. They will do the utmost to dissuade him from such a fatal step, and the knowledge of the intense grief and humiliation he may give them, though not perhaps able to shake his resolve, makes the struggle more deadly and sorrowful than perhaps any that poor humanity has to endure in its efforts to be saved.

Given the sheer audacity of the missionary zeal behind the passing of this Act, it should have sparked conversations about the naked Christian intent behind the colonial “reform” of Hindu society. Instead, Hindu society today quite amicably accepts such “reforms” that are constantly imposed through legislation and judgements, despite their primary purpose being wholly Christian.

Below is a lamentation from missionaries – as per their accounts, since the women in the family were not as exposed to the outside world as men were at the time, they more fiercely resisted conversion, which then further impeded their prospects with the men.

And the religious position of women powerfully affects that of men. The former being intensely ignorant and superstitious, have the most erroneous and dismal ideas of what it is to become a Christian. They will move heaven and earth to prevent what they deem such a calamity, and the influence of a mother’s, a sister’s, or a wife’s tears and entreaties, may well be supposed to weigh heavily when the mind contemplates a change of religion.

On the impact of education on the natives, referring to both Missionary and Government schools (with only a subtle difference between the two in the level of ‘secularism’, as evidenced by missionary literature):

A very wide diffusion of Christian truth has taken place. Our mission schools contain 75,000 natives.

Every year, therefore, thousands are passing out of our schools into active life, instructed in our principles, familiar with our Scriptures, and intimately acquainted with ourselves. A very marked change in religious opinion is rapidly passing over a large portion of Hindu society. Thousands, chiefly connected with rich and high caste families, have drifted far away from the Puranic form of Hinduism — the more recent and popular development of it. They express themselves somewhat thus: — “ Idol worship is a very foolish and superstitious custom. We do not believe in Kali, or Krishna, or Durga, or any of the gods. We worship only one spiritual and eternal God, who has attributes such as are described in your Old Testament. We don’t need a written revelation of religion; nature can teach us all we require to know. Jesus Christ was a very wise and holy teacher, but he was not God, for it is impossible there can be a trinity. How can three be one and one be three? The moral principles taught in the Bible are, on the whole, better than any other we are acquainted with; and your religion is a very excellent one, but it is too good, for how can anyone be expected to keep it strictly. Many of our customs are bad : women ought to be educated a little, and widows should be allowed to marry. It would be a good thing, too, if the Government would prohibit the Mohamedans and Kulin Brahmins from having more than one wife. Indeed our religion and our customs have become very corrupt, just as your religion had become very corrupt before the Reformation.”

This idea that “our religion and our customs have become very corrupt” and therefore require a “reformation” in the image of 16th century Protestant Christianity is a deeply pervasive belief that looms large on the minds of most Hindus to this day, especially as more and more are educated in colonial and/or convent schools. It is, however fascinating to read this admission, coming directly from a missionary who knows full well the intended outcome of missionary school education. There are so many other strands of thought mentioned in the above extract that are still prevalent today as well – for instance, being ‘spiritual but not religious’ and ‘a belief in God but not in rituals’ etc. However, the last line referring to the reformation is particularly powerful, given that it is the driving force for the Hindu reformist project, whether then or now.

On Christian indoctrination in missionary schools – the “elevation” of “heathens” by brainwashing them with Christian values to tear them away from their roots:

The moral tone and character of all who receive the education described is elevated and corrected; they are more honest, truthful, temperate, and manly than the heathen around them, and they as certainly excel the students of the Government colleges. It is often, indeed, very interesting to watch how far they are under the unconscious power of Christianity. Their modes of reasoning on moral questions are mainly Christian, even when they deny the divinity of our faith.

The reference to students of Government colleges being under the “unconscious power of Christianity”, after having been educated in Christian moral codes and “modes of reasoning” based in Christian scripture is quite reflective of the colonial worldview that has persisted and continues to be imparted to Indian minds in the modern Indian education system.

Similarly:

In almost all cases, when the students remain even a moderate time, there is the annihilation in their minds of some of the greatest obstacles to the evangelization of the people. All belief in the existence of gods and goddesses, all confidence in the Shastras, all reverence for caste, are destroyed: the whole system comes to be regarded with contempt, derision, and dislike. Various reasons may lead to outward conformity with the requirements of Hinduism; but all faith in them is swept away.

A straight line may confidently be drawn from the colonial/missionary education system that persisted in India even after Independence, and the attitudes of young Indians that emerge from such a flawlessly Christian model towards Hinduism and Hindu society. Christian ideas imparted insidiously do untold damage to the continuity of Hindu traditions by creating contempt for their religious texts, beliefs, gods and goddesses –

Among those who reach the upper classes in these institutions, there is not one in thirty who leaves with any convictions that the popular religion is either good or true.”

Another extremely relevant passage, which exhibits the true impact of the Westernisation of India, is one which we could safely say that most “modern” Hindu reformers would agree with even today.

Our railways, our steamboats, our electric telegraphs, and even our military prowess, have convinced them that we have a higher civilization than their own, and a far larger amount of material prosperity. They have seen, in some cases, the manifest superiority of our customs to their own; this has disposed them to change. In not a few instances they have gained largely by accepting what we have been disposed to give. The emoluments open to those who receive a good English education are of this nature. Thus the stagnant pool of Hindu society has been stirred. Thought has been stimulated; comparisons have been made; change and reform have been rendered practicable, and these have largely tended to weaken Hinduism, and prepare the way for Christianity.

While under the erroneous impression that “reform” of Hinduism is inherently positive, viewed as a step in “forward” on a linear scale of “progress” and/or “modernisation”, they continue on a path of endless criticism and alteration of Hinduism, not realising that the whole endeavour is straight out of the missionary playbook of the early 20th century.

Along the same lines, an excerpt from “Carey and the land of India” by Henry K. Rowe, published by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in 1910:

The railroads do much today to break down the system of caste, to introduce western ideas to the people of the East, and to link together the western world with the East.

Serious obstacles lay in the way of missionary success from the beginning, and these were not removed with the removal of the opposition of the Government. Caste was a continual hindrance.

Then the work of the English government is breaking down the old systems of the Indian peoples. Education and government and the railways are doing much to destroy caste; and when the caste system falls, Hinduism must go with it.

Modern Hindu reformists may not realise it, but it is quite well-established, especially if we examine missionary and colonial literature that the last line in the above passage is quite prophetic of the consequences of the destruction of caste, and therefore, we often see that the agenda of anti-Hindu and anti-national ideologies is to attack caste.

Further passages from Rev. Storrow’s book detail the augmentative impact of internal reform or neo-Hindu movements such as the Brahmo Samaj inadvertently helping the Christian cause. Hindu reformers that speak of “rationalism” in reality serve the missionary cause by distancing the Hindu from his traditions and beliefs.

Hinduism, it has been proved, is not impregnable. Every phase of it has been studied and refuted. Some of its most venerable customs have ceased. Idolatry gives place to Vedantism, Vedantism to Rationalism, Rationalism to a species of Unitarianism, and Unitarianism to Trinitarian Christianity. Thus, by different roads and with varying speed, do multitudes leave the old faith; but the current which bears most of them on its bosom sets in toward the haven of Christianity.

Another striking notion of the modern Hindu thinker is an utter disregard and even contempt for custom, in favour of a staunch belief in the power of law, though the latter is typically a top-down or an external imposition rather than implicit and localised. The dominant role that traditional customs play in the life of a practising Hindu is still severely understated, perhaps deliberately. Missionaries, however, had a relatively accurate grasp of the primacy of customs in maintaining a code of conduct in Hindu society.

Everyone seems disposed to sink his individuality into the general life of the community to which caste attaches him. Custom has the force and the power of law, and no one ventures to disobey her. We ever ask, in reference to a practice or a usage, “Is it right? “ — “Is it convenient? “Is it reasonable?” They, on the contrary, simply inquire, “Is it the custom?“

The following lines from the book “India and Christian Opportunity”, written by Harlan Page Beach, an American missionary (published 1905 by the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions) serve as another instance of how powerful and sweeping the effect of a law can be, and how opportune changes introduced by the colonial government at the time continue to mould our lives to this day.

In India, the joint-family system prevails, according to which its members for three generations live together, where this is possible. Not only do they dwell together, but they hold all things in common, no member of it having the right to claim anything as his own. We thus have in India the patriarchal system, which minimizes the individual and magnifies the family unit. With the incoming of Western ideas, the educated classes of the Empire are becoming restive, but steps have been taken to modify the whole regime. The recent introduction to the Madras Legislature of the so-called ‘ Gains of Learning Bill ‘ is the first serious attack made upon that system. By means of this bill, which was introduced by an orthodox Hindu but which is not yet passed, an educated man could claim the exclusive right to ownership of all properties acquired by him through his education. Thus, for the first time in India, an individual might claim, apart from the family, that wealth which was acquired by himself. This bill has brought opposition from the public because it conflicts with the rights of the joint family and is a serious blow to all the old Hindu family privileges.

This goes back to M.N.Srinivas’ remarks on joint family cited earlier on in this article, in the context of pre-modern India. Several religious leaders even in contemporary India continue to emphasise the integrity of the quintessential Indian (joint) family and the challenges of aligning traditional family values with modernity.

The impact of early British colonial laws on Hindu society for “reform” is a subject that is under-emphasised. While the ethical considerations can be debated, not enough attention is paid to the motivations behind these reforms, and Indian textbooks even eulogise them as positive, even necessary changes without adequate contextualisation. The “Hindu Gains of Learning Act, 1930” is one such important law that weakened the foundations of the Hindu joint family structure in India, as mentioned in the excerpt above.

Notwithstanding the derogatory reference to Hindus as sheep or pigeons, below is an interesting observation. Modern Hindus’ reductionist perception of caste as some sort of an oppressive social system or simply an occupation-based hereditary compulsion, etc. is doubly tragic since missionaries seem to have formed a better, or if not ‘better’ then at least a more holistic and more nuanced understanding.

‘Indian caste of today is a hereditary institution that is at once social, industrial, religious, and, to some extent, racial in character.

.. the points considered most essential in caste are food and its preparation, intermarriage within the same caste only, hereditary occupation, and a peculiar sympathy with the whole caste, which, taking the form of initiativeness, leads an individual Hindu to follow the example of his caste, just as a sheep or a wild pigeon follows the example of the flock. These ideas also may so far explain the ground of the local variations observable in the custom and usages of the same caste. In one place a Hindu will consent to do what in another he would peremptorily refuse to do, simply because in the former he is countenanced by the example of his brethren, and not in the latter; just as a flock of sheep or pigeons may, from accidental causes, somewhat vary its habits or movements in different localities.’

On the utility of caste to the common Hindu, taking into account social and employment security, and the important role of caste in upholding the morality of society, especially during trying colonial times when Hinduism was doggedly attempted to be stamped out of existence:

There are undoubtedly benefits connected with caste. Missionaries have noted its value in the matter of securing the economic advantages of division of labour and the protection coming from the larger caste family. It promotes to some extent cleanliness and is a moral restraint in certain directions. It has also proven its value to the British Government from a political and policy point of view; it has kept alive a learned class that might otherwise have been blotted out of existence. To the higher classes, it has been a temperance element of great value in that it forbids the use of liquor. Caste has made the Hindus content with their lot, and the system has always upheld a certain standard of morals by its exaction of obedience.

The evils of caste are endured without protest, except among the more enlightened. Indeed some of the greatest sticklers for the institution are found among the very lowest, even the outcastes.

One must wonder whether the supposedly “low” castes would be so steadfast in their conviction if caste did not benefit their social standing and conserve their cultural singularities. In addition, that caste “kept alive a learned class which might otherwise have been blotted out of existence” is an especially poignant point – due to the existence of caste-based propagation of knowledge systems, Hindu epistemology, intellectualism and theology was able to survive religious persecution, both during the colonial era and especially during Islamic rule. In the same vein, Hindu art traditions such as crafts, sculpture, metalwork, textiles, etc. that the British deliberately (and in some cases successfully) tried to squash in favour of selling low-quality industrial goods in the Indian market only survived due to the hereditary nature of passing on certain skills and knowledge.

“Caste is the cement” which should be undermined to pave way for Christianity. Bishop Spencer said:

Idolatry and superstition are like the stones and brick of a large fabric, and caste is the cement. Let us undermine the common foundation, and both will tumble at once.’

Indian reformers of the era surprisingly echoed the words of missionaries, having been convinced that caste was somehow a hindrance to ‘progress’ – whatever that entailed.

The Indian reformers, differing in many ways, are of one mind in denouncing caste as the great hindrance to progress and social and physical improvement. Babu’ Nagarkar, of Bombay at the Parliament of Religions, maintained that ‘ the abolition of caste is the first item of the program of social reform in India. Caste,’ he said, ‘ has divided society into innumerable cliques and killed healthy enterprise. It is an unmitigated evil, and the veriest social and national curse. All our domestic degradation is due to this pernicious system.

It is interesting to note that reformers then (and now), were all on the same side as the Christian missionaries when it came to the labelling of caste as a social evil that was a hindrance to ‘development’ (in the Western sense of the word). Needless to say, missionaries had/have very different plans for India once caste was eliminated and faith in Hinduism was degraded.

On India’s village system being a small yet independent unit with a proportionately greater capacity to facilitate the creation of an environment most suited to self-actualisation and spiritual well-being:

India’s village system is somewhat unique and very interesting. In the form which it assumes throughout most of India, it is a microcosm, as complete in itself and as independent of outside support as is possible.

This union of the village community, each one forming a separate little state in itself, has, I conceive, contributed more than any other cause to the preservation of the people of India through all the revolutions and changes which they have suffered, and is in a high degree conducive to their happiness and to the enjoyment of a great portion of freedom and independence.

The impact of a fast and rapidly urbanizing India on the Hindu psyche, unfortunately, doesn’t get as much attention as it deserves from mainstream Hindu intellectuals.

On caste as an instrument of religious traditions:

Caste is at every point connected with Hinduism, — a thing interwoven with it as if Hinduism were the warp and caste the woof of the fabric of Indian life. Personal responsibility for one’s own morals and religion thus becomes merged in the caste’s views and practices, and the individual conscience is lost in the ethical judgments of others. Custom thus becomes the practical god of all Hindus, and in no land is religion so dominated by society interpretations of it.

Caste is found to be a purveyor of religious functions, with custom being a “practical god”. The ‘warp and woof’ analogy is particularly notable, and this observation perhaps explains the prevalence of caste despite all sorts of attempts at its extirpation.

This excerpt below is prophetic of the ideology of neo-Hindu reformers, be it Keshub Chandra Sen’s tryst with Christianity or the proxy Christianity of many of today’s reformers –

The various samajs and eclectic systems of to-day are thus the resultant of contact of the Indian mind with Christian truth and institutions, leading to a return to the Vedas and to the amalgamation with them of many Christian ideas. Most of these movements are merely half-way houses between Hinduism and Christianity. They are with faces more or less turned toward the light and possess the progressive spirit, which, in some cases, can not fail of landing their members at no distant date in the Christian fold

When it came to the missionary strategy, the targeting of “lower” castes, who were perhaps more disenfranchised due to various factors, and the “upper” castes required different approaches. While concerted efforts and resources were focused on the “low” castes, it was acknowledged that taking these “outposts” would not shake the very foundations of caste, which was said to be a veritable “citadel” of Hinduism – and therefore mission schools were engaged to gain access to indoctrinate the “upper” castes.

Principal Sharrock of the Anglican College at Trichinopoly, agrees with the Bishop that efforts to win the higher castes should not at the present time be increased, but that all available resources should be concentrated on the low castes who are so ready to be brought into the Church. At the same time, Mr. Sharrock insists on other considerations also: “(i) That caste is the citadel of Hinduism, and the taking of the outposts will not appreciably affect its power of resistance; (ii) that schools are the only way by which missionaries can get access to Hindus of the higher castes ;

Preach to every creature; disciple both high and low. Let no difficulties deter, no seeming slowness of advance dishearten or discourage. Attack all along the line. Take the outposts; yes, and storm the citadel too. Pierce the rocky mountain from both sides. And having done all, stand and wait for God!

A few passages from “Catholic Missions In Southern India To 1865”, written by Reverend William Strickland and T. W. M. Marshall, author of “Christian Missions” are surprisingly instructive as to the precision with which missionaries understood caste, which stood sentinel in the “preservation of public morality” and the conservation of “patriarchal” customs (all caste-based customs are undoubtedly not patriarchal, and this particular characterization itself is based in colonial presuppositions – but that is a discussion that falls beyond the scope of this article). Caste is not only acknowledged as the glue that kept society rooted but also as an insurmountable barrier to those who sought to convert the faith of the people.

“The subdivision of the nation into castes, though under different names, prevails everywhere, and is everywhere materially the same. The caste of an individual is determined by his birth, and by birth alone; and it is this system of caste which is, as it were, the keystone of Hindoo social life. It has enabled the Hindoos to preserve their nationality, in spite of repeated conquest, and has hindered their being absorbed by their conquerors. Although centuries have elapsed since the Mahommedan conquest, and the Mussulmans have been settled in large numbers over the face of the country, yet they remain quite a distinct arid separate people. Though they have domineered and tyrannised over the Hindoos, though they have robbed and plundered them, still the follower of Brahma has kept aloof from the despised Moslem, and no relationship or inter-course of family life has ever existed between the two races.

The assertion may appear strange, yet indisputably this division of the people into different castes has contributed immensely to the preservation of public morality, and the conservation of the patriarchal customs which still exist in the country”

As stated above, though caste may have its disadvantages, it invariably gave “powerful support to those social distinctions which constitute society” – presenting a clear contradiction to the stance of today’s Hindu reformers that caste in itself was the reason for rather than a deterrent to religious conversions.

Those who would allow no fear of God or man to check them in their evil courses, tremble before their caste, and dread that sentence of exclusion which would at once deprive them of the friendship and intercourse of their nearest kindred, and send them as vagrants through the land. In vain the Mahommedan power strove to crush this system — the English were too politic to attempt to meddle with it.

Here we have another passage illustrating the missionary argument to exercise “moderation”, that is, restraint in lieu of overzealousness in preaching the “annihilation” of caste – as to do so against such an ingrained institution would invariably provoke an uprising.

“Doubtless the distinction of castes,” observes the Bishop, “ is here carried to a ridiculous and often unreasonable extreme; but to aim at destroying it abruptly, to seek to confound all ranks and conditions, and to make an onslaught on that which immemorial usage has consecrated, would be to excite revolution in the country, to injure the interests of religion instead of serving them, and to enter on an idle pursuit of a result which could never be reached”

A few more lines from the same book, that quoted discussions that took place during a missionary conference are as follows:

….Caste is universally acknowledged to be the strongest bulwark of Hinduism, and the greatest obstacle to the spread of Christianity…

For the time being, let us agree to the common assertions that the people of India do not mind having two or three religions, and that as long as you do not demolish their family loyalties or slander their caste prejudices, they will not disturb you, even though they do not agree with your doctrines.

The phrases “strongest bulwark” and “greatest obstacle”, though superficially dramatic, carry weight as are used by missionaries themselves, making this entire argument more difficult to dismiss as being biased or even “brahminical” – an opinion further consolidated by a similar declaration from the Edinburgh Report in a section detailing the obstacles to Christianity in India:

The great social hindrance is the existence of caste.”

In Hindu India, caste is spoken of as a complex of tyrannous obligations constituting the great social hindrance to Christianity.”

Reverend William Strickland’s views on caste are consistent with those reiterated in most contemporary missionary literature. This may also explain the tenacious persistence of caste despite the evolution of an increasingly atomized individualistic society.

What attaches every Hindu, and even the lowest pariah, to his caste, is that it is his only protection against a sea of troubles; it is his nation, his clan, his trades union. Outside his caste, all men are alien to him; within it alone he can look for sympathy, brotherhood and protection. He clings to it like a sailor to his ship; as a soldier, while in an enemy’s country, to his regiment.

The striking similarity between Hindu reformers of the 19th century and 16th-century European reformists in their intended goals was even noticed by missionaries of the time, who made comparisons such as that of Dayanand Saraswati of Arya Samaj with Luther – further cementing the fact that Hindu ‘reform’ was conceptualised in the image of Protestantism.

Pandit Dayanand Sarasvati became finally emancipated from the authority of Brahmanism in some such way as Luther became emancipated from the authority of the Church of Rome. Luther appealed from the Roman Church and the authority of tradition to the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments. Pandit Dayanand Sarasvati appealed from the Brahmanical Church and the authority of Smriti to the earliest and most Sacred of Indian Scriptures. The watchword of Luther was ‘Back to the Bible’; the watchword of Pandit Dayanand was ‘Back to the Vedas.’

These lines below, from India, One Hundred Years After on reformist tendencies are valuable – be it the Hindu reformer or the missionary, both wish to disintegrate what “is”, and no matter who is responsible, ultimately, it is Christianity that benefits:

Secondly, as a more positive sign of disintegrating tendency, mention should be made of the reform movements of Brahmanism, such as the Aryo-Samaj and the Brahmo-Samaj, now numbering hundreds of thousands of members. The more intelligent and sensitive souls of the sacerdotal caste in increasing numbers are revolting from the superstition, ignorance and immoralities connected with crass Hinduism. Whether their reforms turn backwards to the ideals of their ancient literature or reach forward in a desire to build upon Christian ethics, the significance is the same. There are not a few sincere and pure-minded men among the Brahmans who, while not formally accepting Christianity, yet recognize the moral teachings of Jesus as necessary for society. These men do not refuse to Christ the highest place as a religious teacher and leader.

In another missionary study titled “Christian Missions And Social Progress A Sociological Study Of Foreign Missions Vol I” by Reverend James S. Dennis, who was a Students’ Lecturer on Missions at Princeton and a member of an American Presbyterian Mission himself, the position that caste is central to the Hindu faith occurs yet again:

The influence of caste penetrates the innermost recesses of the spiritual life, and reaches to the uttermost bounds of outward conduct and habit, concerning itself with the most trivial as well as the most dignified aspects of daily experience.

Similarly, Reverend Dennis quotes Sir M. Monier- Williams on the “overshadowing mastery of caste regulations” in a section about “non-Christian” social evils:

It is difficult for us Europeans to understand how pride of caste as a divine ordinance interpenetrates the whole being of the Hindu. He looks upon caste as his veritable god, and thus caste rules, which we believe to be a hindrance to the acceptance of true religion, are to him the very essence of all religion. They influence his whole life and conduct.”

Another book by Robert E. Welsh, a Presbyterian minister who also took part in missionary work, titled The Challenge to Christian Missions: Missionary Questions and the Modern Mind, speaks of the impact of the entire cumulus of ‘Western modernity’ on the “rule of caste”, offering contentions that are surprisingly accurate, given that it was published over a century ago in 1906.

Railways, commerce, and the whole mass of Western civilisation will in any case proceed irresistibly to break up the rule of caste and race-custom and the superstitions of the unsophisticated.

Welsh also elaborates on the terrifying effect of a “secular” education provided by the Indian Government, which directly aided the missionary cause by brainwashing their “most intelligent youth” by imposing “new ideas and foreign habits”, thus making them undermine their native faith and culture. This phenomenon is arguably still observed across schools today, despite three-quarters of a century having passed since India achieved independence from a Christian imperial power.

“Our commerce, with its ships — like shuttles weaving the web of a common lot and life — with its explorers, prospectors, traders, and railways is penetrating to the recesses of every country. Our science, taught in their schools and books, is undermining the foundations of their superstitions. They are sending their most intelligent youth to be educated further in our colleges and law-schools. Over 100,000 of the most receptive minds in India bear the mental imprint of the foreigner’s tuition, and they go out into the community with their old faith shaken at its base. The Indian Government, by providing state education for India’s youth, is as much responsible for this result as are the missionaries. The Government policy, indeed, is more perilous, for it supplies teaching in secular knowledge alone, and is thus breaking down the old altar without providing anything to take its place. Western civilisation is marching irresistibly upon the people. Its new ideas, foreign habits, revolutionary knowledge, are invading their ancient preserves and even showing in their temples.”

Welsh goes on to say that given the rapidity of the pace with which the Western civilisation was replacing the old world, the dissolution of religious and spiritual structures would inevitably lead to a vacuum that could only be filled by Christianity.

If these rude races or old-world nations are not morally seized and uplifted by Christianity, the old pagan order will fall to pieces all the same, and there will be no new moral and spiritual force set at work to create a new and better order with finer restraints and higher law and custom.

A germane question we must ask ourselves here is, what would be the moral and spiritual system that is being formulated by Hindu reformist intellectuals for when the old pagan order falls to pieces?

These next lines (also from Welsh’s book) on the government curriculum taking pride in inculcating ‘godlessness’ are extremely telling, and shockingly relevant to date:

“Your Government schools take credit for abstaining from religious teaching of any sort, and in due time you will have on your hands a race of young men who have grown up in the public non-recognition of a God. The indigenous schools educated the working and trading classes for the natural business of their lives. Your Government schools spur on every clever small boy with scholarships and money allowances, to try to get into a bigger school, and so through many bigger schools, with the stimulus of bigger scholarships, to a University degree. In due time you will have on your hands an overgrown clerkly generation, whom you have trained in their youth to depend on Government allowances and to look to Government service, but whose adult ambitions not all the offices of the Government would satisfy. What are you to do with this great clever class, forced up under a foreign system, without discipline, without contentment, and without a God?”

Welsh quotes English journalist and editor of The Spectator, Meredith Townsend, on the subject of the hindrance to the progress of Christianity in India, wherein he mentions that the convert is required to “break caste”, and that caste was not compatible with Christianity:

Mr. Townsend believes caste to be “a form of socialism which has through ages protected Hindu society from anarchy and from the worst evils of industrial and competitive life — an automatic poor-law to begin with, and the strongest form of trades union.” But “caste in the Indian sense and Christianity cannot co-exist.”

The following extract from “The History of Christianity in India: From the Commencement of the Christian Era: Second Portion: Comprising the History of Protestant Missions, 1706–1816” written by Reverend James Hough who was a Chaplain to the East India Company at Madras further consolidates this view, albeit with an additional (false) diatribe against Brahmins, who were regarded as their major intellectual adversaries that prevented the Gospel from reaching more ‘heathens’, as mentioned earlier in this article.

This system of caste, then, must be considered a religious distinction. It is an artful contrivance of the Brahmins to hold the millions of Hindostan in bondage; and it presents a more formidable resistance to the propagation of Christianity in India than any other impediment.

This is from the notes of another missionary — “The pioneers: a narrative of facts connected with early Christian missions in Bengal, chiefly relating to the operations of the London Missionary Society”. Powerful lines.

It is often supposed that caste in India has now almost come to an end. But caste and Hindooism may be said to be synonymous terms; and only when caste comes to an end will Hindooism cease to exist.

From “India and the Hindoos: being a popular view of the geography, history, government, manners, customs, literature and religion of that ancient people; with an account of Christian missions among them” by F. De W. Ward, a missionary at Madras – an edifying analysis of whether caste is inherently (and only) a social or a religious institution:

Is caste a civil or religious institution? Both, I answer; but eminently the latter. The distinctions it establishes are of Divine decree, and subjects of sacred record. Its effects upon all social relations are immediate and direct, but without the religious element it could not have retained its vitality so long, and produced such results as we now witness. It will occur to my reader that caste presents a formidable barrier to the progress and triumph of Christianity in India. It does so; one of the most formidable that can be named or conceived. It prevents the Christian teacher from gaining that free and familiar intercourse with the people, so important in securing for the truth deliberate examination, and an impartial judgment. All foreigners are considered as belonging to the lowest class, and are, therefore, forbidden that social intercourse at the table and in the family, which furnishes so favourable an occasion for giving a personal direction to his public instructions. The state of heart produced by this institution is unfavourable to the reception of Bible doctrine and spirit.

In a book by Reverend William Buyers, a missionary at Benares, titled “Letters On India: With Special Reference To The Spread Of Christianity” is a passage bemoaning the rules prohibiting natives from close contact with missionaries, thus preventing them from forming more personal relationships that would considerably ease conversion. It captures the frustration of an agitated missionary who feels powerless despite great efforts in a society with strong rules.

The principal difficulty which we meet from caste, is that it prevents us from obtaining that free and familiar intercourse with the people by which we might have full and fair access to their hearts and affections. We labour among people with whom we are not permitted to eat or drink, and into whose families we can scarcely find any mode of entrance. We may preach from town to town, and street to street; but from house to house we cannot. There is a line of demarcation between them and us, which we cannot pass.

Nearly all our intercourse with them is therefore of a public nature; what they are in private we can with the utmost difficulty find out. How then are we to reach the feelings of their hearts, without which public discourses are dull and inefficient?

Everyone who has observed the vast influence of private conversation and social intercourse in promoting religion, must at once see the great disadvantages under which we labour, among a people who regard us as an unclean race, with whom they can neither eat nor drink, nor form any intimate relation. Thus the main springs of all their finer feelings are almost entirely beyond our reach. We are to them barbarians and they are barbarians to us.

In consequence of this estrangement of the Hindoos from all other nations arising from caste, we are prevented from living among them on intimate terras as friends and neighbours, and gaining that easy access to their affections, by the interchange of good offices, which would enable them to understand our principles and motives, so as to produce on their minds a favourable impression with respect to our religion. They are by no means insensible to kindness, but in consequence of caste, everything must be done at such a formal distance, that it is next to impossible so to overstep the boundaries as to get near their hearts. This is not so much the fault of the people as of the system of caste which leads a Hindoo very naturally to look on a man of another nation, as a being of almost another species, with whom it would be preposterous to think of forming any close relation.

Reverend Buyers continues, expressing his frustration regarding the lack of access to the native, due to the multitude of caste-based rules, regulations and prohibitions:

Were it not for this state of separation from all other people, resulting from caste, it would not be so powerful a barrier in our own way. It is not merely the difficulty that a native convert has in leaving his caste, that obstructs Christianity, but that of getting access at all to his mind and heart while he continues in it.

On the barrier formed by caste and familial structures that attenuated the effect of proselytisation:

A oneness is necessary between the teacher and the taught, but caste comes in as a gulf between the Christian and the Hindoo which neither can pass. In this country, the European is a stranger and a barbarian to all around, and however anxious he may be to avoid it, caste draws such a line of demarcation between him and those around him, that he must continue a stranger and a barbarian for life.

The peculiar construction of families in India forms an obstacle in the way of Christianity perhaps even more powerful than that of caste, with which, however, it is so closely connected, that the two influences are scarcely distinguishable.

Joseph Mullens, a missionary that worked with the London Missionary Society in Calcutta in his book “A Brief Review of Ten Years’ Missionary Labour in India Between 1852 and 1861” also conveyed a similar disdain for caste being a hindrance to the spread of Christianity.

The strong bond of caste is, in my view, the chief obstacle in the way of their making an open profession of the Christian religion.

This passage below is from “Mission Schools in India of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions: with Sketches of the Missions among the North American Indians, the Sandwich Islands, the Armenians of Turkey, and the Nestorians of Persia” by Reverend R. G. Wilder, published 1861; once again reiterating the experience of missionaries with a few personal testimonies:

The Rev. Myron Winslow, D.D., after some thirty-five years of labour among the Hindus, says: “The obstacles to the missionary work in India are great. There is a hereditary priesthood, an ancient and extended literature; immemorial and time-indurated custom; the- iron and adamantine barrier of caste; a cruel but fascinating superstition, controlling every action; and inconceivable love of sin”

The Rev. Dr. Scudder testifies: “If I were asked to tell in one breath what I thought the mightiest present obstacle to the onward course of the Gospel in India, I should unhesitatingly, say caste. It is a monster that defies description. Caste has its hold on every sinew of the Hindu. Its bitterness is diffused through every drop of his blood. Its threads are woven into the very texture of his soul. Caste gives form and life and strength to the Hindu religion. Hinduism would soon be shivered to atoms if it were not for caste. This is Satan’s masterpiece. The more I look at it, the more I am struck with the cunning of the great Deceiver, in so skillfully- forging and so firmly riveting upon this people the fetters of caste. No one can conceive of its universal power and its- malignancy until he comes in contact with it. It stands directly in the way of the Gospel like a mountain with immeasurable base and sky-reaching summit”.

Rev. Scudder calls caste ‘Satan’s masterpiece’ that “gives form and life and strength to the Hindu religion” – a singular insurmountable hurdle between the heathendom and its Christianisation. It is almost wondrous to see so many members of the clergy working with missions on the ground come to precisely the same conclusion in different accounts interspersed across missionary literature, spanning almost a century.

How do we reconcile with the fact that our ‘Hindu’ reformers of today and the past have desired exactly the same things as missionaries w.r.t destroying caste? The missionaries clearly had decidedly different motives!

These lines are from India, One Hundred Years After, a quarterly published in 1913 by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, written by Secretary Cornelius H. Patton, on the specific subject of the influence of travel to Europe and Westernisation on natives

As surely as those high caste men made that journey, saw the life and institutions of Europe and became immersed in Christian civilization, so surely they came back changed men. When to the influences of travel you add the study of western science and history, and the impalpable influence of western life and thought in its impact upon the Orient, it is evident that caste must give way and Brahmanism loses its distinctive power.

In “Hints on Missions to India”, Miron Winslow, a Missionary at Madras, shockingly sees caste as an obstacle greater than idolatry itself.

There is caste, which is not found in the same form in any other country. It is an obstacle, greater than idolatry itself. This is a hydra-headed monster, which not only lives, when one head after another is cut off, but pushes out new heads in place of the old; and can be fully slain only when consumed in the fire of divine love, kindled by the Spirit of God.

The consistency of the missionary position on caste is shocking. Reverend J. P. Jones in “Modern Hinduism: Does it meet the needs of India?” views caste as the “greatest curse which has ever befallen a people, keeping them in religious and social bondage”, that caste was a religious institution of divine authority that hindered Christianisation, despite, arguably, its faults in terms of aspirational possibilities.

They are also very unlike the people of the West. Among Westerners religion is largely an incident in life. It has a separate department, and a small corner in the life of a man there. In the East, on the other hand, religion enters into every detail of life. There is hardly a department or an interest in life which is not subsidized by religion and which has not to be conducted in a religious way. That which obtrudes itself upon all sides and which is, perhaps, the most determining factor of modern Hinduism is its caste system… One has well said that Hinduism and Caste are convertible terms.

That brings us to the end of the survey on the opinions of missionaries on the significance of caste.

The truth is that if Hindu society is keenly observed, one would realise that caste is synonymous and inextricably intertwined with Hindu religious customs, traditions, and Dharma itself. Since the pursuit of hereditary occupation by caste is certainly voluntary in a free society as it stands today, the effort to better understand caste is solely in order to navigate the unchartered waters of theorising a holistic economic, religious and social system that could possibly serve as an alternative to our current developmental trajectory. The other motivation to better understand the history and nature of caste is to preserve the enormous cultural memory and praxis that the numerous castes of India have been passing on for generations, which is severely endangered by the reformist project of caste annihilation and/or dilution. Demonising caste as a ‘brahminical’ creation is neither pragmatic, nor rooted in truth, nor does it ultimately aid in providing a haven for the safeguarding of diversity, pluralism and mutual respect that Hindu castes have carried forward for millennia, through thick and thin.

Patronizing and aggressive reformism is pervasive in Hindu society today, whether in the form of neo-Hindu religious leaders and public intellectuals, or institutions that reflect a troubling colonial legacy and use a dangerous amalgam of shallow interpretations of scripture and Christian morality to coerce Hindus into “modernity”. Reform, if any, should ideally be as organic as possible, and at the very least must be examined in order to verify whether a victim of the fallacy of Chesterton’s fence* before being implemented post-haste.

*Chesterton’s fence is the principle that reforms should not be made until the reasoning behind the existing state of affairs is understood. This quotation is from Chesterton’s 1929 book ‘The Thing’, in the chapter entitled “The Drift from Domesticity”:

In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it”

Simply put, don’t ever take a fence down until you know the reason why it was put up.

Caste is indeed the equivalent of a Chesterton’s fence for Hindu reformers. While we may well proceed to tear it down, we need to have an acute awareness of the reasons it was constituted and what functions it performed for society as a whole. Hopefully, this discussion gives rise to the formulation of feasible alternatives which could compensate for our losses and question the dominant zeitgeist of our times. A serious reading of early missionary literature certainly offers a lot of clues in this regard.

Now that we are better placed compared to where we were more than a century ago to resist such insidious yet sweeping forces that have the potential to replace our civilisation as we know it, we must begin to recognise and repel them and reimagine a different future.

Leave a Reply