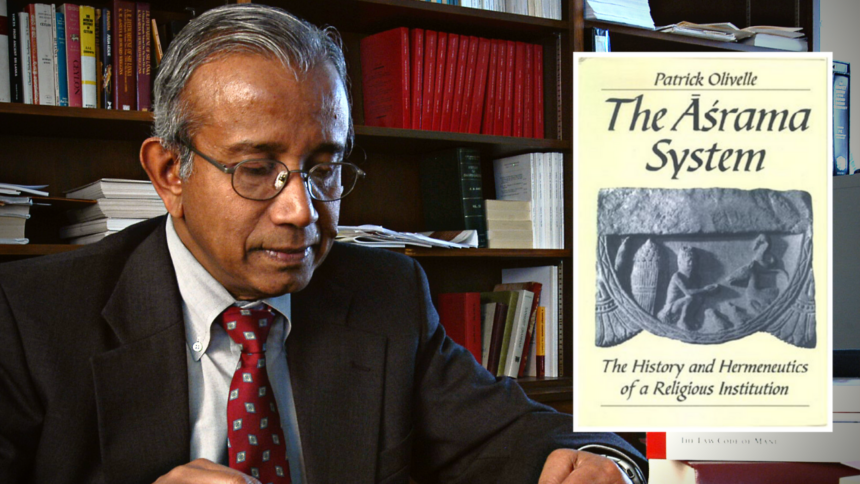

Varṇāśramadharma – considered by many to be the very essence of what we know as Hinduism- has been a subject of intensive scholarship and debates among historians, sociologists and even political commentators. However, much of this attention has been predominantly directed at varṇa; by contrast, Āśrama has been a relatively less explored area. In his book on the “Āśrama System”, Patrick Olivelle tries to fill in the gap and gives us new insights into the history and workings of this system, thus expanding our understanding of Indian history and Hinduism even further.

The first problem that one encounters while investigating any historical event or process is the problem of semantics. Terms that have certain meanings today may have had an entirely different, even an opposite, meaning years ago. Thus, Olivelle argues, the definitions of Āśrama and Āśrama system needs to be cleared first. Based on his study of Sanskrit grammar and the liturgical-theological texts like the Saṃhitā-s and the Brāhmaṇa-s, he argues that the word Āśrama is derived from the root verb √śram or śrama- meaning “to toil, to labour, or to exert oneself”. In Vedic literature, śrama is mostly used in the sense of toiling for sacrifice. Often it is the very synonym for sacrifice or the creation and procreation effort it symbolises. As ancient Indian texts often associated a definite pattern of behaviour or conduct with a specific place or region, thus, Āśrama-s came to be defined as “houses” (Niketan) and modes of lifestyle sanctioned by Vedic theology, that were conducive for the performance of the Vedic sacrifice and/or austerity. The Āśrama System is an outgrowth of this original definition. Olivelle argues that this system was a theological construct, designed to impart theological meaning to the institutions and values associated with the various modes of Vedic lifestyle and then classify/arrange them under the broader rubric of “Dharma”.

Based on these definitions, Olivelle comes to certain conclusions regarding the method to adopt in order to study the Āśrama System. These are as follows-

- History of Āśrama system has to be distinguished from the institutions comprehended by it

- Since Āśrama is a theological construct, normative and theological texts are proper sources for tracing its history

- In investigating the system’s origins, motives and circumstances surrounding the same; only the earliest known formulations should be considered

- Attention has to be paid to the hermeneutical basis of the system to evaluate its history.

Based on these conclusions and findings, Olivelle argued that not only the general public but also scholars have an incomplete understanding of Āśrama. The original “Āśrama System,” described and debated in the Dharmasutra-s and most likely dating from the fifth to fourth centuries BCE was not a “stages of life” scheme. Rather, it consisted of four permanent and adult religious modes of life, chosen after the Vedic graduation ceremony (Samāvarttana) and before marriage (Vivāha). These are – student, householder, forest hermit and renouncer. None of these modes of lifestyle had anything to do with age as a factor. One could be a perpetual student or a perpetual renouncer. The initiatory Vedic education was distinguished from the Āśrama of a student. Furthermore, the institutions that were a part of this construct existed independent of the system. What, then, was the need for such a system to emerge?

According to Olivelle, the original Āśrama System arose in a time of immense social change in which older Vedic values were challenged by new religious systems emerging both within and outside the Vedic fold. These new systems were based on visions of liberation that were agnostic to ritualism and propitious to asceticism. This contrasted sharply with the older Vedic ideal of the married, sacrifice-offering, son-begetting householder. Above all, they were expressions of the choice-exercising individual. It was in this context that the original Āśrama System was created by “forward-looking” and “reformist” Brahmanas who were sympathetic to these ideas and wished to bring them under the ambit of Dharma. Their purpose was to confer legitimacy upon freely chosen ascetic lifestyles and blunt its novelty by showing that it was sanctioned by the Vedas. We find this new attitude reflected in the Upaniṣad-s, which often question the attachment to rituals and emphasize the goal of ultimate liberation that can be achieved through knowledge and renunciation. Olivelle’s view is in marked contrast to the usual generalization that historians have often succumbed to; that of equating any new development or innovation within Sanātana Dharma as some kind of appropriation of Shramanic ideology- mainly Buddhist or Jain.

The creation of this original “Āśrama System”, however, took place over centuries. It involved intense debates among Brahmanas. Both sides- those who opposed and those who supported the new system- utilized hermeneutical strategies to advance their case. Orthodoxy held that the Vedas are the highest source of Dharma. Thus, if any custom or injunction is violative of the Vedas (irrespective of its sanction by the Smritis or by custom), it stands null and void. This principle, known as Badha (forcing a choice by denying the validity of alternatives) was employed by orthodox scholars like Gautama and Baudhayana in the Dharmasutra-s to argue that the Āśrama System is violative of Vedic Dharma. This is because the ṛṇa (Debt) that an individual owes- to the Gods, Ancestors, Seers, Humans and other non-human living beings- cannot be paid without leading the life of the householder. It is only the married householder who can perform sacrifices, beget children and earn a livelihood. Without paying these debts, men incur infamy and sin upon their death. Thus, the orthodox Vedic view upheld the Aikasrama (One-Āśrama) view.

The proponents of the Āśrama System, on the other hand, adopted the hermeneutical strategy of Vikalpa (admitting the authority of all and accepting an option). This meant that if there were any inconsistencies between various injunctions of the Vedas, any of the options might be chosen as valid. This meant that references to celibacy and asceticism in Vedic literature were to be understood as endorsement for renunciation. This is how the original Āśrama System came to be adopted, based on divergent (in comparison to the orthodox) interpretations of verses of the Brāhmaṇa-s and Upaniṣad-s. The shift in orthodoxy was visible in the younger Dharmasutra-s of Apastamba and Vashistha. Unlike their predecessors, they accepted the legitimacy of the Āśrama system. The only caveat they added was that all the four modes of life were equally legitimate.

Olivelle also delves into the other subcategories that arose inside the system during the Early Medieval period. Though all stages were classified, the classification of Saṃnyāsa– the fourth Āśrama– was the most essential. Saṃnyāsa was divided into four subcategories: Kutichaka , Bahudaka , Hamsa and Paramahamsa. The first two sub-categories, as described in the Saṃnyāsa Upaniṣad-s and Vaikhānasa–Dharmasūtra, are remarkably similar to the old descriptions of the forest hermit. This also demonstrates how the third Āśrama was quickly becoming archaic.

The growing influence of asceticism, emergence in the formation of Mathas and famous scholar-ascetics like Ādi Śaṅkarācāryaḥ, was evident in articulations of a state “beyond Varṇa and Āśrama”- Turiyatita and Avadhuta- a veritable fifth Āśrama. Even the stage of Paramahamsa was privileged over the other stages, based on the concept of Jivanmukta (liberated while living in the human body). Such individuals were thought to have transcended all good and evil, pure and impure, and thus; beyond Dharma. However, while a consensus had arrived over the Classical System, these new attempts to glorify asceticism did not go unchallenged. While Advaitins supported this exaltation of asceticism above all else, Vaishnavas and other theists opposed such assertions as “proto-Buddhistic” and even contended, using the Yugadharma hermeneutical technique, that Saṃnyāsa is forbidden in the kaliyuga (Kalivarjya). The conflict between the two competing conceptions of Dharma persists to this day.

The author also examines the Āśrama System’s interaction with categories and institutions like as Gender, Varṇa, Civil Authority, and Puruṣārtha-s. While evidence from theological and normative literature suggests that women were generally forbidden from engaging in asceticism due to their deemed inability to gain such knowledge, their mental and physical nature, as well as the need to preserve society’s reproductive capacity. Literary texts and even the Itihāsa-Purāṇa tradition show that there were women seers who meditated, lived as hermits in forests, performed sacrifices, and even engaged in theological discussions. Similarly, while normative texts generally disapprove of Śūdra-s adopting renunciation and consider them to be outside the Āśrama system, we see in some later day texts not only the acceptance of Śūdra householders as Āśramika-s but also their gradual acceptance as renunciates, particularly within the Purāṇic–Bhakti and Tantric traditions.

With the rise of asceticism and monastic institutions in society, the royal authority had to take notice. Monastic complexes, like other corporate groupings or guilds, had their own laws and properties, which the King was tasked with upholding and protecting. It also had an impact on civil law in terms of property inheritance, marriage, and so on. The act of renunciation was considered as a “civil death” of the person; thus, from that point onwards, the person’s possessions might be inherited and even divided by his sons. Along with death, impotence, and disappearance, renunciation of the husband was recognised as a reason for the remarriage of women.

There was no consensus, however, on how the Puruṣārtha-s (Dharma, Artha, Kāma, Mokṣa) are to be equated to the Āśrama-s and Varṇa-s. Even equating the Āśrama-s with Varṇa-s proved problematic. The general approach was to associate Mokṣa solely with Saṃnyāsa, and Saṃnyāsa only with Brahmanas. But this was just a theory. In practice, as we see from the historical evidence, women and Śūdra-s adopted asceticism in many instances.

Patrick Olivelle’s research helps us realize how Hinduism evolved over time and what role the Āśrama system had played in this evolution. He questions the common assumption of the “unchanging” and “static” nature of Indian society and culture. Drawing from the work of Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann, Olivelle shows “when we scratch below the surface, even an institution seemingly as immutable as the asrama system has undergone drastic changes over time and has been the subject of continuous controversy and debate.” However, the concept of changelessness or immutability fosters the sense of continuity required for a stable social order in the face of constant social and cultural change.

Vedic exegesis or hermeneutics (Mīmāṃsā) in India has created such a sense of continuity. The exegete generates and preserves the stabilising sense that the present is more like the past than it actually is by discovering new meanings in ancient texts and traditions and old meanings in new ideas and practices.

It raises the intriguing prospect of employing hermeneutics not only for the study of religious traditions but also for the study of “ancient” and complicated cultures in general. It also demonstrates how Hinduism has kept a sense of continuity with the past by balancing orthodoxy and dynamism.

Leave a Reply