INTRODUCTION

The colonials attempted to understand the country in the framework of castes and tribes. Post-independence, we could not get rid of these divisive notions. Unfortunately, identifying groups as ‘Hindu’ and ‘tribals’, implying a difference, encouraged focussed evangelism on the latter. However, the same tribals become Hindus when convenient. A Muslim as an education minister for almost a decade after independence; a left-oriented academia setting our educational discourses; and Nehru’s apathy towards traditional India set the foundation for a sustained intellectual attack on Hinduism with lasting consequences. More severe than the colonials themselves they undermined the essence and foundation of Hinduism.

The post-colonial era continued the deracination and de-rooting of Indian intellectuals as effective as the colonial education system. The continuing debate on the status of tribals of India and how they connect to ‘mainstream’ Hinduism has a single purpose of breaking India. At even a more fundamental level, it stems from ignorance of what Hinduism means. Hence, among the many breaking forces in India pitting one against the other, the tribal narrative becomes an important one. This essay tries to understand how this narrative is presently playing out in the legal, constitutional, social, and religious contexts. The essays rest on the works of Dr. SN Balagangadhara Rao, Dr. Koenraad Elst, and Sai Deepak.

DEFINITION OF ‘TRIBES’ AND ‘HINDUS’

Article 366 (25) and Article 342 define the identification of tribal societies in India. It says in effect that the President, with respect to any State (in consultation with a Governor) or Union territory, by public notification, specifies the tribes or tribal communities which enter the list of Scheduled Tribes for that State or UT. The Parliament may, by law, include or exclude the communities from the list of Scheduled Tribes specified by this notification. Once included, there can be no further modifications.

The listing of scheduled tribes is State/Union Territory-wise and not on an all-India basis. In terms of demographics, the total population of Scheduled Tribes in India is 8,43,26,240 (8.2 % of the total population, urban share 2.4 %) as per the Census 2001. The criterion to identify a tribe, though not explicit in the Constitution, has become well established as a result of various studies across time: primitive traits; distinctive culture; geographical isolation; shyness of contact with the community at large; and backwardness. Each of these criteria is subjective, ambiguous, and many times circular. To date, through nine such orders, each state and Union Territory has a list of its own tribes except Haryana, Punjab, and some Union Territories.

On the other hand, the Indian Constitution is yet to clearly define the word ‘Hindu’. Various acts like the Hindu Marriage Act (1955), Hindu Succession Act (1956), and the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act (1956) however define the scope of the word ‘Hindu’ as:

- any person who is a Hindu by religion in any of its forms or developments, including a Virashaiva, a Lingayat, or a follower of the Brahmo, Prarthana, or Arya Samaj;

- any person who is a Buddhist, Jaina, or Sikh by religion;

- and any other person who is not a Muslim, Christian, Parsi or Jew by religion, unless proved that the group of the person does not fall in the ambit of Hindu law or custom.

There is some circularity here too (A Hindu is a person who is a Hindu…) but this is in essence Savarkar’s definition of Hindus too.

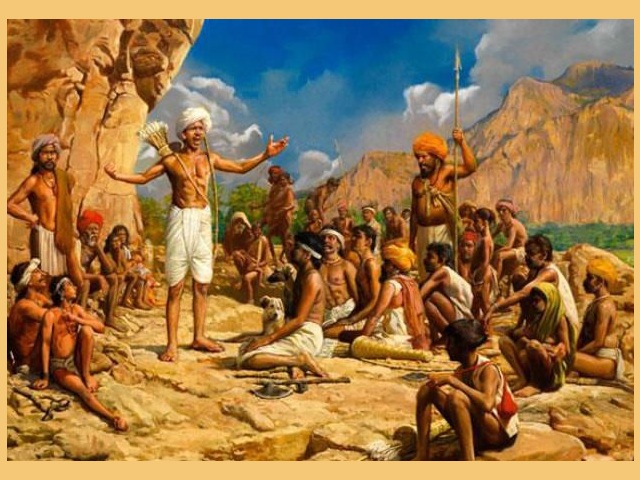

ADIVASIS, COLONIAL CATEGORIES, AND THE ‘ORIGINAL INHABITANTS’

The neologism Adivasi (adi, original; vasi, inhabitant) of the 19th century, a Sanskrit word, is hardly a self-description of the tribals. This became the most successful disinformation campaign of modern times by the colonials, Christian missionaries, and Indian secularists say Koenraad Elst (Who Is a Hindu). The classical story (Aryan Invasion/Migration Theory) proclaimed that the Aryans came to India in the middle of the second millennium BCE and pushed the original Dravidians (to the south of Vindhyas) and the tribes (into the forests and the hills). Those who stayed became the low castes and the untouchables (a part of the caste system and yet outside it). In this colonial understanding, the ‘tribes’ were distinct from the category called the ‘caste.’

In settler colonies (America, New Zealand, Australia), ‘aboriginal’ made sense to distinguish the European settler from the natives. However, in non-settler colonies like India, the term ‘aboriginal’ became a pure colonial construct. In this construct based on vicious Aryan theories, the urban and the agriculturally advanced peoples became the ‘majority’ group. These were the Aryan invaders who chased away the original inhabitants or imposed upon them. Ironically, the colonials had imposed a new word Adivasi on certain groups, says Elst. Attempts to term these forest dwellers or mountain dwellers with their Sanskrit classic descriptions as atavika, vanavasi, or girijans is now considered ‘saffronisation’ and rewriting of history. Thus, a strong narrative now pits the majority dominant Hinduism (originally foreign invaders) against the ‘original’ inhabitants, now minorities (the non-Hindu tribals and the Hindu untouchables). This imaginary division of the Indians as ‘natives’ and ‘invaders’ is a permanent colonial legacy.

J Sai Deepak (India That Is Bharat) quotes the works of S.K. Chaube and Susana Devalle which discuss the creation of tribal identities in India. The former discusses the facilitation of conversion of the tribes of the North East to Christianity and the latter explicates how the tribal construct in India formed a colonial legitimizing strategy. This ideology remained intact in the post-colonial era and gradually integrated into a caste structure. Devalle says about the Jharkhand tribes: A creation of European origin, tribe was one of the elements through which Europe constructed part of the Indian reality. They were basically peasant societies inserted in a class society. There were in fact no tribes in Jharkand. This colonial categorization as ‘tribal’ is at best, out of place, and, at worst, ahistorical and sociologically groundless.

In the post-colonial era, other international forces strengthened the idea of tribes and indigenous people as Sai Deepak shows. Among the earliest organizations to work on issues related to ‘indigenous people’ was the ILO (International Labour Organization) which adopted the Indigenous and Tribal Populations Convention in 1957 and later in 1989. Both use ‘tribe’ and ‘indigenous peoples’ interchangeably to distinguish them from national communities of former colonies. As a result, the distinction between ‘dominant national communities’ and ‘indigenous/tribal peoples’ when applied to Bharat introduces an internal coloniality and a permanent faultline where the minority tribal communities become racially and culturally distinct from the ‘majority national communities,’ says Sai Deepak. The majority, by implication, are simply the pre-European colonizer of the tribal minorities.

The now distinctly separate people become the focus of intense evangelical activity. The tribal minorities become ‘religious minorities’ and hence pitted against Hinduism. The mischief cannot be so complete. Our subaltern studies also highlight this aspect even as the intellectuals swallow this line of thought hook, line, and sinker. Thus, the international tools are thoroughly colonial in their view of the Indian world and our colonial consciousness allows us to retain the view.

The UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations in Geneva has been looking into the claim of some tribal spokesmen that the Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes of India are the ‘indigenous population’ of India. Fortunately, the government of India has taken a strong stand on this and has been able to convince the UN group so far that there is no clear-cut separation between tribal and non-tribal segments of the population. Koenraad Elst quotes eminent sociologist Prof. Andre Beteille who feels that most tribal groups show in varying degrees elements of continuity with the larger society of India. Beteille says, ‘…The consciousness of the distinct and separate identity of all the tribes of India taken as a whole is a modem consciousness, brought into being by the colonial state and confirmed by its successor after independence.’

Dr. Koenraad Elst says, ‘To traditional Hinduism, tribes are simply forest-based castes or communities (with both ‘caste’ and ‘tribe’ rendering the same Sanskrit term ‘jati’), in contact with the Great Tradition. There never was a clear cleavage between Hindu castes and animist tribes. Some were less Vedic yet socially integrated; others were less Vedic and socially more isolated like the castes now labeled tribes. But even the latter never had the consciousness of belonging to a separate ‘tribal’ type of population even though they were intensely conscious of their individual identity…Tribes from Afghanistan to the Gonds of South-Central India have strongly resisted the Muslim invaders… The tribals may have lived on the periphery, but it was still within the horizon of Hindu society.’

Interestingly, as Elst points out, anthropologists deny that the tribals of Jharkhand and North-East are the original inhabitants. They say that Tibeto-Chinese speaking communities (Northeast India) and Austro-Asiatic speaking ones (East India) immigrated to India in ancient historical times and met with existing indigenous Indian populations living already on their migration routes. Thus, some of these ‘tribes’ migrated much later after the indigenous non-tribal peasant population. Hence, the historical data do not support the division of India’s population into ‘aboriginal tribals’ and ‘non-tribal’ invaders.

ANTHROPOLOGISTS, SOCIOLOGISTS, AND INDOLOGISTS ON TRIBES

This section is a summary of what Dr. Balagangadhara Rao (Cultures Differ Differently) says about the notion of tribes in the country. Typically, a tribe is a group of people with a common language, culture, rules of social organization, territory, and descent. However, all these characteristics are subject to exceptions. Another notion says that tribes are a pre-state type of political organization less hierarchical, less centralized, and smaller in scale than “the state”. Problematically, many of the best-known “tribes”, were the exact opposite.

The concepts of race and tribe are in the dustbin of the social sciences academia even though getting rid of them has proved difficult. The impossibility of defining the term ‘tribe’ and its broad usage is responsible for its incoherence as a category. Looking at the word’s negative and even pejorative connotation, anthropologists started using the term ‘ethnic group’ with shared land, language, history, and cultural traditions. Scholars feel that ‘tribe’ is a key but obsolete concept from anthropology’s early history that usually served colonial, administrative, and ideological purposes to mainly paint the local groups as “primitive” or “backward”.

Indologists have played havoc in their ‘knowledge generation’ in India. Indologists use discredited theories from earlier social sciences to put across outlandish claims regarding a culture about which they are ignorant. Contemporary social sciences draw upon these ignorant claims to put across equally outlandish claims about human societies and cultures, again in ignorance of what the Indological claims rest upon. The social sciences and Indology enter a death dance where neither participant dies but knowledge does, says Balagangadhara Rao (Balu) quite strongly.

Indologists think that the fundamental unit of the Vedic society was a ‘tribe’. The Vedic people were apparently organized into five major tribes. Other kinds of social groups constituted these ‘tribes’: a collection of extended families forming a clan; a collection of clans making up a tribe. The ‘tribes’ were led by ‘a rajan’ (king or chieftain). Further, the Indologists tell one of the tribes, by combining a set of hymns, established a religious, political, and social centralized authority. Thus, ‘the’ Vedic religion was a state religion established by an ‘emperor’; simultaneously, it was also a religion established by ‘the priest’ that ‘controlled’ the masses because there was no state in Ancient India to control people! Writers have based themselves on such conjectures on fragmentary texts from 3000 or more years ago to speculate on the nature of Indian society, says Balu.

The renowned Vedic scholar Witzel uses ‘classes’ as the equivalent of ‘varna’. He believes that an incipient class (varna) structure (nobles, priest/poets, the ‘people’), is organized in clans (gotra), tribes, and occasional tribal unions. Our knowledge of human societies tells us that social classes do not and cannot structurally organize a society into a tribal society (i.e., into a society whose constituting social units are tribes). That a class might consist of members from different tribes or clans but a social class is not a tribal aggregate. Witzel’s ‘society’, organized into tribes and clans by an ‘incipient’ class structure, is sociologically impossible. It is even more impossible that the tribe structures as tribes by social classes like the ‘noble’ (the ‘high’ and the ‘low’ nobility), ‘priest/poets’, and ‘the people’. The incipient class structure of Witzel allegedly organizes the ancient Indian society as an association of tribes. If ‘incipient’, how did Witzel ‘discover’ their presence, existence, and structure?

Could all of this be from reading a single Rig Veda verse (10.90) of an Indian text almost three thousand (or more) years old? If this is possible, Rigveda is a sociological text par excellence and its bards would put a Weber, a Durkheim, a Veblen, and a Parsons to shame, says Balu. If Witzel is right about ancient India, we have a society of a kind hitherto unknown to historians and social scientists undercutting multiple domain theories in social sciences today. More plausibly, Witzel’s claims about societies, tribes, and classes are either nonsensical or false. Anthropologists or sociologists have been unable to develop a coherent understanding of tribal societies, yet that does not prevent Indologists from making uncontrolled speculations based on fragmentary texts.

TRIBAL-HINDU KINSHIP

Going by Savarkar’s definition of a Hindu as someone who regarded this land as both the Fatherland and Holyland, the so-called aboriginal or hill tribes are Hindus undoubtedly. Despite all the negative characterization of Savarkar, the modern constitutional definition of Hindu has the closest resemblance to his idea. There are certain important points while considering the intimate Hindu-tribal kinship:

- The ancientness of the Hindu religion itself to the pre-Aryan times makes it as ‘aboriginal’ as the tribal populations. Dr. Koenraad Elst quotes Shrikant Talageri who proposes that almost every aspect of Hinduism (idol worship, saffron color, forehead tilak, the idea of transmigration of souls, the ritualistic calendar or Panchanga, the zoomorphic aspects of Hinduism, the wide distribution of sacred places in the country, and so on) as we know it today is of ‘pre-Aryan’ origin before the middle of the second millennium BCE. Assuming the Aryans to be true, Hinduism is practically a ‘pre-Aryan’ religion adopted by the ‘Aryans’.

- The similarities between Hindu traditions and the tribal traditions in their fundamental polytheistic nature and a paganism (deifying the feminine, nature, and animals) show them clearly distinct from the prophetic-monotheistic religions. Both Hindu and tribal traditions fail to see a conflict between the principle of unity and the principle of multiplicity. Hindus worshipping trees (Tulasi, bilva, ashwattha) or snakes makes them equally ‘animists’ like the tribals. Significantly, the worship of ancestors and nature spirits makes the tribals definitely non-Muslims and non-Christians, but they are in fact closer to Vedic Hinduism. Reincarnation is a common belief of both Hindus and most tribal populations not only in India but across the world.

- Anthropological data has clearly disproved the constant narrative that the tribals have no caste system or a hierarchical social system in contrast to the Brahmanical traditions. Tribes the world over and in India (Polynesian tribals in the Pacific Islands, the Batwa and Baoto tribes in Congo, The Khova tribes of the Nort-East, the Gonds of Bastar, the Mundas, the Ho of Chhotanagpur, the Santhals, and so on) practice various forms of caste distinctions, endogamy groups, strict commensality practices, and even untouchability. In some tribal groups, the punishment for marriage outside the caste is death. Tribes have never constituted a single endogamous unit.

Koenraad Elst writes (Who Is a Hindu), ‘Before Independence, the census had a category ‘animist’ or ‘tribal’, which contained 2.5% of the population…The Constitution and the census in independent India do not recognize this broad category of ‘animism’ any longer. Depending on the context, they classify the non-Christian tribals as Hindus for legal purposes; or put them under the heading of each tribe’s own ‘religion’ separately. In tribal areas, special protections for tribals (not as a religious but as a sociological category) exclude non-tribal (Hindus and non-Hindus) from ownership or habitation inside the tribal ‘inner line’. The ambiguity of the tribal position vis-a-vis Hinduism allows for terminological manipulation. So, when convenient, as for polemical purposes to increase the incidence of ‘Hindu’ polygamy, tribals (along with Buddhists and Jains) are Hindus who now constitute 80% of the population. Otherwise, they are not, and in that case, Hindu discourse treating tribals as Hindus becomes an objectionable ‘assimilative communalism’ or ‘boa constrictor’. The religious categorization in India cannot be more politicized.’

A cultural mutual influence exists, including Sanskritization, across centuries in varying degrees. This kinship has been a slow organic process since antiquity without any violence or conversions. Pre-Harappan cave dwellings contain cultic elements which are still existent in Hinduism today. Living Hinduism continues many practices from tribal antiquity. So far, the distribution of different cultural practices and worldviews in Hindu society and in tribal-animist society is not such as to indicate a clean religious cleavage between those two.

RELIGIONS AND TRADITIONS– THE WHY AND THE HOW QUESTIONS

Perhaps, it makes the best sense to understand the tribal identities in India in the framework supplied by Dr. Balagangadhara who questions whether religions truly exist in India. He proposes that if Islam, Christianity, and Judaism classically are religions, then there are no religions in India. As a corollary, if what we have in India are religions then Islam, Christianity, and Judaism are not religions. Indian traditions do not meet the basic criteria of religion in the form of A Book, A Church, A Messenger, and One True God by any stretch of the imagination.

India is a huge conglomerate of traditions that the colonials experienced as ‘Hinduism’. They saw many practices, rituals, sampradayas, paramparas, gurus, philosophies, and such, which they united into an overarching meta-narrative or the ‘religion’ of Hinduism. Later came the ‘religions’ of Sikhism, Buddhism, Jainism, and so on, many times allegedly revolting against the main ‘oppressive’ religion of Hinduism. ‘Hinduism’ was thus an experiential unity for the colonials who were trying to make sense of Indian culture. Their own culture generated the strong idea that religion is a cultural universal. A culture without religion was unimaginable for them. Our social sciences, heavily colonized, never questioned these colonial understandings.

Religions have characteristically monotheism (generally a male single God), a single important prophet, exclusivity, a stress on conversions (even by violence), a belief in the truth of its own doctrines, and ‘tolerance’ as a solution to deal with non-believers. In contrast, traditional cultures (Greco-Roman world of the past, India) have the characteristic features of: polytheism; deification of the feminine, animals, and nature; conversions looked upon as unethical, and an indifference to differences as a solution to deal with pluralism. Traditions too place a premium on truth. The practice of Vada (debates) is intense in the Indian land. However, the difference is that religions say, ‘I am true and you are false’; traditions say, ‘I am true but you are not false’.

Rituals form the basis of traditions and these help in uniting people. The learning configuration of such a traditional culture is the ‘how’ question in contrast to the ‘why’ question of a religious culture. Traditions however evolve- merging, dissolving, and exchanging with other traditions organically without involving physical violence. Jain traditions, Buddhist traditions, and even orthodox darsanas (or philosophies) like Yoga, Samkhya, Nyaya, and Vaisesika have no special need of a god in their expositions. This indifference to differences allows traditions to survive without the threat of violent personal attacks in case of different opinions. This also allows a person to hold multiple views and believe in multiple ‘gods’ too in a typical traditional culture.

The ‘why’, important for religious cultures, becomes secondary for traditional cultures. Indians thus struggle to find an answer to questions like ‘what is the purpose of the Bindi’, ‘why is the cow revered so much’, ‘is linga puja a fertility cult’, and so on. The simple answer that ‘it is a tradition’ fails to satisfy the scientifically-minded typical westerner and the modern Indian. Traditional cultures ask ‘the how’ question (like how best one should perform the ritual) and bring people together. Western cultures, rooted in religion, ask the why and gives rise to science and atheism. Balu says that while calling oneself a ‘Hindu’ might be convenient, the danger is in trying to develop ‘doctrines’, ‘theologies’, ‘catechisms’, and our own ‘Ten Commandments’ so that we could identify people that follow a religion called ‘Hinduism’. Intellectuals, in India and in the West, are transforming some of the multiple Indian traditions into a single ‘religion’ called ‘Hinduism’. The problem does not lie in trying to unify diversity into unity. Rather, it lies in trying to fit traditions into the straitjacket of ‘religion’.

India is a land of traditions. Calling oneself a ‘Hindu’ for the sake of convenience is a continuation of ancestral traditions. There is also no need for a ‘reason’ to keep ancestral traditions alive. This is what traditions are and this is how we learn them. ‘Tradition’ does not refer to the presence of some specific component but picks out a totality. In fact, absences or minimal presence of a specific component do not make it any less of a tradition. Attempting to encapsulate traditions as ‘beliefs’ or ‘rituals’ or ‘festivals’ is to distort their nature.

Traditions are extremely dynamic and flexible. Whether one smokes, drinks alcohol, eats meat, goes to temples, performs rituals or not, one can be a part of a tradition. There is also no authority to pronounce whether someone based on his or her personal habits is a part of tradition or not. This does not suggest that traditions are either fluid or amorphous. Importantly, traditions distinguish each other as traditions. Dr. Balu says, today, we are not yet able to make sense of the presence of these two properties: (a) the enormous flexibility in belonging to a tradition and the sharpness with which the boundaries exist between traditions; (b) the possibility that any element could be absent from a tradition and yet it could maintain identity and distinction.

Reason functions as a brake on excesses of human practice. No Indian tradition has ever denied this crucial role of reason. To the colonial narratives, which Indian intellectuals internalized as colonial consciousness, justifying a practice by referring to an age-old practice is equivalent to justifying a practice ethically. This gross misunderstanding of tradition makes for silly questions about the nature of Indian traditions. The notion of ‘truth’ to characterize practices is to commit a category mistake. As human practices, traditions are neither true nor false, whereas some descriptions of such practices could be either true or false. Heresy is significant by its absence in Indian culture despite the innumerable traditions, sharp disagreements, and polemics between people. This fight between ‘truth’ and ‘falsehood’ never raises its head in a land of traditions. In such a framework of understanding traditions, it becomes explicit that a continuum and intermingling of practices makes the distinction between the so-called Brahmanical traditions and the tribal traditions difficult, ambiguous, artificial, and to a certain extent mischievous. The ‘neti-neti’ (not this, not this) definition of a Hindu thus stays intact: anyone who is not a Christian, Muslim, Jew, or Parsi.

CONCLUSION

The colonials, in trying to understand an alien culture by their categories of ‘castes’, ‘tribes’, and ‘Hinduism’, were probably not acting out of any malice. They were looking through their European frameworks which included the race theories. More importantly, after independence, we lost a great opportunity to set the discourses right. Our social sciences, political systems, and legal and constitutional machinery failed brilliantly across decades to do something which our traditions never needed to do: to develop a theory of varna, jati, tribes, and religions in our frameworks. It simply accepted the western frameworks of caste, sub-caste, discredited racial theories, and religions to understand ourselves. It is one of the saddest aspects of the Indian education system that despite being an integral and intricate part of the social system, nobody has a clear idea of what varnas, jatis, or kulas actually mean.

Caste and sub-caste grew in western contexts; varna and jati grew in the Indian contexts. Applying the former to understand the latter (which may be a completely different phenomenon) has caused immense cultural damage. There was no attempt to understand Indian society through our own eyes; not only that, we perpetuated the western narratives vigorously. The political and legal systems now perpetuate a most ubiquitous ‘caste system’ by dividing the country into various caste and tribal groups and then proceeding to take care of each segment. Positive discriminations (reservations in institutes of higher learning, parliament, government jobs; promotions) have been the most important outcome of this understanding of our varnas and jatis as castes. Simultaneously, it accepts that the caste system is evil and ugly and needs to go! It also gets surprised when national and international agencies keep identifying India by its caste system only. As a country, we have been intellectually lazy to set new narratives to heal wounds and assuage anger.

The narrow political goals have been the reason for the increasing atomization of the country with just about everyone having a sense of injustice as a group. As eminent economist, Dr. Bhikhu Parekh says, ‘Justice is generally an individualist concept; the due to an individual based on his qualifications and efforts. Justice needs redefinition obviously in non-individualist terms if social groups are subjects of rights and obligations. We should also demonstrate continuity between the past and present oppressors and oppressed. We must also analyze the nature of current deprivation and that it is a product of past oppression conferring moral claims on the oppressed. These questions are important in India where positive discrimination has no roots in the indigenous cultural tradition and is much resented.’

There is no difference between the tribal cultures and Hinduism. It is all one. The tribals are an unfortunate focus of intense evangelization in the North-East by the Christian missionaries. In certain communities like the Nishis, such conversions have disrupted severely the social and cultural fabric of coherent societies. Such disruption has never happened in the interaction between the ‘mainstream’ and the ‘minor’ traditions with their characteristic dependence yet independence as is usual in a traditional pagan land. The examples of many ‘tribal gods’ in the country (Sammakka-Sarakka in Telangana, Jagannath Puri cult) clearly unite the Hindus and the ‘tribal’ communities into one large whole. Divisions are wholly unnecessary and even mischievous. Talageri says that the revival, rejuvenation, and resurgence of Hinduism includes not only religious, spiritual, and cultural practices springing from Vedic or Sanskritic sources but from all other Indian sources. The practices of the Andaman islanders and the (pre-Christian) Nagas are as Hindu in the territorial sense, and Sanatana in the spiritual sense, as classical Sanskritic Hinduism.

Koenraad Elst writes, ‘If we go by the historical definition, the question whether tribals are Hindus is very simple to answer: they are Indians but not prophetic-monotheists, so they are Indian Pagans or Hindus. They have many elements in common, partly by distant common roots, partly by the integration of tribal elements in the expanding literate Sanskritic civilization, and partly by the adoption of elements from the Vedic-Puranic Tradition in the tribal Traditions.’ As Balu rues, the anthropologists spent about 100 years attempting to get rid of a pernicious and incoherent concept like ‘tribe’ only to see it sneak back in, via Indology and other social sciences, into the Indian Constitution, Indian legislation, and their administration.

FURTHER READINGS AND REFERENCES

- Who is a Hindu? Hindu Revivalist Views of Animism, Buddhism, Sikhism, and Other Offshoots of Hinduism by Koenraad Elst. The chapter ‘Are Tribals Hindus?’ is a great overview of the arguments which disprove the notion of a cleavage between the ‘main Hindu’ traditions and the ‘tribal’ traditions.

- Decolonizing the Hindu Mind: Ideological Development of Hindu Revivalism by Dr. Koenraad Elst. A fundamental sourcebook to understand the entire spectrum of political Hinduism.

- Cultures Differ Differently: Selected Essays of S.N. Balagangadhara (Critical Humanities Across Cultures) Editors: Jakob De Roover and Sarika Rao. The last three chapters (The Vedic Society and a Brain Stasis; The Indology and Sociology of Varna; Knowledge, Bullshit, and the Study of India) brilliantly detail the extreme violence that Indologists and sociologists across centuries have caused to the country’s cultural and social fabric. It is an urgent read for anyone with even a trivial interest in seeking solutions for India.

- The Heathen in His Blindness: Asia, the West, and the Dynamic of Religion by S. N. Balagangadhara. This book explains the core hypothesis of Balu that there are no religions in India but only traditions. This framework gives the only explanation of why India dealt so efficiently with multi-culturalism across centuries. We need to rediscover this solution always existing within us for the increasing strife in the world arising from pluralism packing in smaller geographical areas: to traditionalize our religions with characteristic indifference to differences rather than religionizing our traditions making them hard and intolerant.

- Do All Roads Lead to Jerusalem? The Making of Indian Religions by Divya Jhingran, S N Balagangadhara. This is a simplified version of the above book.

- The Poverty of Indian Political Theory by Dr. Bhikhu Parekh

- India that is Bharat: Coloniality, Civilisation, Constitution by J Sai Deepak

Leave a Reply