Exploring the idea of apaurusheyatva of the Vedas.

APAURUSHEYATVA OF THE VEDAS: Part 1

Disclaimer: This piece by Dr. Pingali Gopal is with permission from Chittaranjan Naik. The article is a summary of a five-part article written by Chittaranjan Naik on an online forum for discussing Advaita. The ideas and the themes solely belong to the latter. Dr. Pingali Gopal claims no expertise or primary scholarship in the subject matter. The purpose of the article is to hopefully stimulate the readers to explore further. One can access the full article here:

APAURUSHEYATVA OF THE VEDAS BY CHITTARANJAN NAIK

**********************************************************************

INTRODUCTION

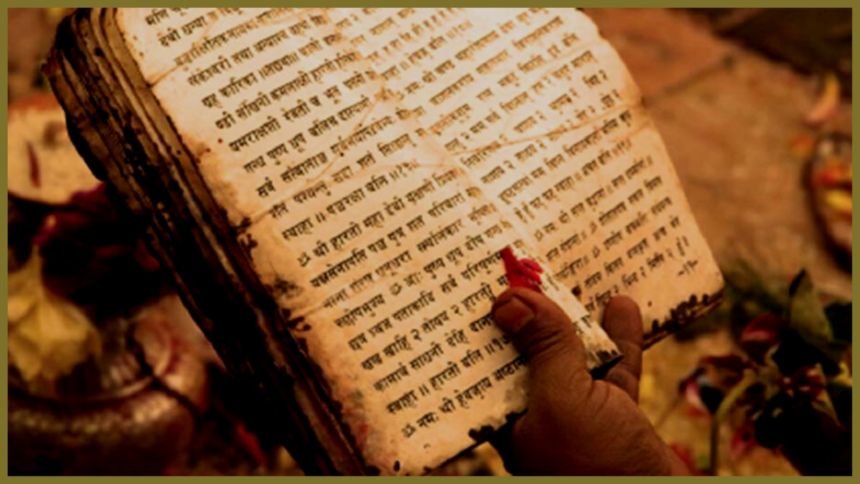

Growing up in Indian culture, to the question by any inquisitive child ‘Who wrote the Vedas?’, the typical answer by a family adult or a spiritual guru or teacher would be that they have no human author or are apaurusheya. Most of the time, the answer satisfied us and we raised no further questions because that is how beings in Indian culture behave when the claims of our scriptures do not exactly tally with our school history and geography lessons. As we grow older perhaps, the historicity of our texts starts troubling us and it becomes sometimes difficult to believe that the Vedas could be both eternal and without a human author. It is more convenient for us to believe that humans do not have proper historical records of the ancient times and apaurusheyatva means that we do not know the names of the author(s) of the Vedas. However, this discomfort does not come in the way of most Indians holding a deep value to Indian scriptures, especially the Vedas. The scriptures and their chanting are still an integral part of our lives.

Advaitic Vedanta remains the pinnacle of our darshanas and its all-inclusive universal vision is indeed the explanation of this (laukika) and the transcendental world (alaukika). Dr. Chittaranjan Naik was surprised in one online forum discussing Advaita that many did not accept the idea of apaurusheyatva of the Vedas. As a response, he wrote a detailed five-part article explaining what this means and how we need to accept and respect this idea. As an aside, Chittaranjan Naik mentions that the establishment of this idea is more detailed and explicit in the Dvaita texts of the Madhavacharya school. Amongst the darshanas (or philosophies), Purva Mimansa argues in great detail to establish the apaurusheyatva of Vedas. Advaita does not spend much effort but accepts the Mimansa doctrine. The author relies mainly on the translations of Jaimini Purva Mimamsa Sutras by Ganganath Jha and the translation of Kumarila Bhatta’s Slokavartika for the article. He did face a lot of difficulties in accessing those important books, a reflection of how lackadaisical we are in protecting our traditions and culture. But that is another story.

THE RELATION BETWEEN APAURUSHEYATVA AND FLAWLESSNESS

There are three primary pramanas (means of knowledge) known as pratyaksha (perception), anumana (inference), and Agama (Scripture). The first two are the means to know about empirical objects whereas the third is the means to know about things beyond the reach of the senses. While there are a great many things that lie beyond the reach of the senses, the primary object to be known by Agama is Brahman only. All other topics are its subsidiaries.

The prameya is the object to be known; pramana is the means to obtain knowledge of the object. Two things are crucial here: (i) adopting the appropriate means and (ii) ensuring that the means are free from defects. An Agama- the means to obtain the Supreme knowledge about Brahman, thus should be free of defects as a necessary condition. However, its flawlessness needs to be known beforehand and not after obtaining Brahmajnana. It, therefore, requires an external mark by which it may be known that it is a flawless pramana.

Agamas are composed of words. Words reside in conscious beings, not in inert things, and they issue out of conscious beings in the form of speech. Now, a defect in a product has always a defect in the producer as its cause. Even if the materials constituting a product are defective as an immediate cause, it remains the defect in the producer for not being able to recognize the defective material. What are the causal factors that cause defects to arise in conscious beings?

There are three capacities that characterize every conscious being: iccha (desire or will as the primary driving force), jnana (knowledge), and kriya (action). Knowledge of an object precedes every action invariably as without knowledge, there can be no motive for action. Action leads to the accumulation of merits and demerits. The store of karma of an individual conscious being, i.e., the cumulative aggregate of all the jiva’s unfructified past actions, is adrshta. By their own nature, the mind, intellect, and the sense organs, are unlimited and without defects; it is a jiva’s past karma, or adrshta, that limits the intellect and sense organs of a jiva and also causes defects to arise in them.

It is the presence of adrshta that sustains the individualities of diverse beings. This is true not only of the jivas born on earth but even of perfected human beings. Thus, any Agama that comes from an individual being, even if such a being is a perfected being, cannot be flawless. Why? Because the perfected being was a jiva striving for perfection before the attainment of perfection. This is the argument that Sri Shankara presents when confronted by the Buddhists with the proposition that the Agamas that have come from Buddha are reliable and flawless. Sri Shankara replies that even if Buddha was a perfected being, still, he is different from God because he has a history of striving for perfection whereas God, being eternally unchanging and immutable, has no history. The emphasis on past history to differentiate a perfected being from the Supreme God is due to the potential effects of adrshta in the former. Perfection removes the ignorance of the (now) perfected being, but it does not nullify that part of accumulated past action (prarabda karma), which continues to operate in the world. Hence, the scriptures that issue out of such perfected beings, cannot be impeccable and flawless.

What about Agamas that have come from God who is free of adrshta and thus any defects? The crucial factor here is the ‘dependency on the adrshta of beings to whom the scripture is given’. Thus, even if God is perfect, the adrshta of the people who receive the scripture limits the scope of the scripture. God is ever full and Self-fulfilled. So, there can never be a motive for His creation. Hence, as an analogy, He creates the universe as a Leela or sheer Sport. The only reason attributable to the actions of God is the adrshta of individual beings. God creates the universe in accordance with the adrshta of beings, and even the Agamas that He gives to people are determined by their peculiar dispositions. Such scriptures, Vishesha Dharma for those specific people, cannot be appropriate pramanas for revealing the Supreme Knowledge of Brahma-Vidya.

The dependency of such scriptures on the adrshta of people brings in the factor of the ‘adhikara’ of those people. It is known from the scriptures that there are many ‘stations’ in the spiritual realm that a jiva may attain, such as apavarga, vaikunta, etc. Therefore, to treat these scriptures indiscriminately as a means for obtaining Brahma-Vidya would be incorrect. The arguments do not necessarily conclude that limits exist even to scriptures given by God. Indeed, there are some scriptures, such as the Bhagavad Gita, which are accepted as flawless. But the vital point here is the possession of an inherent mark by which the scripture becomes flawless and not limited by the adrhstas of people. It is not possible for anyone to know the invisible adrshtas of people nor is it possible for anyone to fathom the reasons that God has in giving specific scriptures to mankind. Thus, it becomes impossible to fix a mark by which one may say with certainty that only particular scriptures originating from God have the scope of being flawless Pramanas.

A scripture for obtaining Supreme Knowledge that would possess such a mark of flawlessness has to be necessarily uncreated, undetermined by the specific adrshtas of beings, and be existing naturally in the Nature of God Himself as an eternal archetype of Dharma. Such a scripture would be independent of the causal factors that cause any of the deficiencies. This Scripture, being uncreated by any being, not even by God, would be Apaurusheya and would be the basis not merely of vishesha dharma but of an Eternal and Universal Dharma, that is, Sanatana (eternal and unchanging). Any scripture that reveals dharma in some aspect or another would have its roots in such a Sanatana Dharma. Only an Apaurusheya Agama would possess both the attributes (flawless and possessing the mark of being flawless) for it to be an unquestionable Pramana for Brahma-Vidya. Any other scripture capable of imparting such knowledge would necessarily be grounded in such a Primary Apaursheya Scripture.

WORDS, OBJECTS, FLAWLESSNESS

A word is a sign that attaches to an (other) object. A word would not be a word if it did not have an object as its meaning. An object also always attaches to a word as its meaning. An object, by itself, can never be flawed. The truth of an object is the thing ‘as it is’. Faults in an object always arise in relation to a valuation that exists in a conscious being. Water simply exits ‘as it is’. If we did not need to drink water, both pure and murky, water would be without any defects attracting the label of ‘fit’ and ‘unfit’. The locus of defects in objects is not in the objects of the world, but in the valuations, desires, and purposes that conscious living beings have.

The same principle for objects does not however apply to knowledge. The latter is not flawed on account of its failure to achieve a purpose but is flawed when it fails to know the object ‘as it is’. This is what adhyasa is – one thing known as another. A flaw in knowledge is essentially avidya and an object known through such a flaw Is adhyasa. This is of two kinds: adhyasa with respect to substance; or adhyasa with respect to attributes. Adhyasa with respect to substance occurs when, though knowing the meaning of both objects, one mistakes one for another (like a rope for a snake). Adhyasa with respect to attributes occurs when the attributes of one object mix up with those of another, as for example, when someone thinks akasha (the sky) curves like a bowl. This happens only when the person does not know the correct meaning of the word, in this case, of ‘akasha’. The meaning of a word, in its nature, ‘as it is’, is yathartha. An adhyasa of both types leads to a corrupted meaning- ayathartha.

How are words and knowledge connected? Knowledge is associated with knowing the words for objects. That is because, in the cognitive act of perception, an object becomes perceived as ‘this’ (its name). There are two kinds of knowledge: a) the identity of the object and b) the nature of the object. Even if one knows the identity of the object denoted by a word, if he does not know the nature of the object, we say that he does not know the object. One may point to an apple correctly but if he says that apples are intrinsically bitter, such knowledge is flawed.

Words reside in conscious beings. The capacity of a word to signify an object in the luminescence of consciousness is its ‘power’ or ‘shakti’. The nature of an object denoted by a word is dependent on the object itself in its nature ‘as it is’. The only mechanism by which a word may appear to denote something else is due to the cognitive operation of mind and intellect through the prism of avidya. The flaw of a word deflected from its object is through the superimposition of attributes that do not belong to the nature of the object. Avidya relates only to jivas. In other words, when there is paurusheyatva, there is potential for a flaw to arise in a word. In an Apaurusheya Reality, there is no potential for a flaw to arise. Scriptures are in the form of sentences. But whether words or sentences, it is knowledge of word meanings. The locus of the flaw is an avidya-ridden conscious being and not the words or sentences themselves.

FAULTLESS TRANSMISSION OF KNOWLEDGE

A word is a sound-form that points to an object and carries its meaning. But a word is an object too because it is a perceived thing. There are words that point to objects in the world, and there are words that point to words. The word ‘cow’ points to a cow; the word ‘word’ points to the word itself. The word ‘Veda’ points to a string of words in a definite order and not to objects in the world. The meanings constitute its subject matter; they constitute the knowledge contained in the Vedas.

In general, knowledge transmits through the process of teaching and learning. Knowledge transmission depends on many factors for its success: the excellence of the teacher, the capabilities of the students, and many other situational factors. Recognizing this fact, the Vedic method of transmission of knowledge is on an entirely different principle. In science, the means adopted to ensure a reasonable degree of insulation against errors of transmission is its openness to the public domain and to peer-review. But for subjects that speak of things beyond the reach of the senses, and which are obtainable only by the rarest of the rare in this world, critiques from the public domain hardly provide insulation against the knowledge being free of errors. Even if a rare person were to obtain such knowledge, who would be there to ascertain that the knowledge of the person is error-free?

The chain starting from the manifestation of the eternal scripture in the mundane world to its continuing transmission in the world would have to be flawless. If instead of relying on the fidelity of the knowledge transmitted to the students, we were to simply record the speech of the teacher we would have achieved our purpose. Irrespective of whether the students have grasped the knowledge taught to them or not, the recording would encapsulate the knowledge because those words in the recording are the carriers of meanings. The knowledge of the subject preserved in the recording would be available to anyone in the future. Vedic method of transmission of knowledge depends on the faithful transmission of the vehicle that carries knowledge – the Word. Now it becomes important to preserve the purity of the Vehicle.

PRESERVING THE PURITY OF THE VEDAS

The six vidyas called Vedangas accompany the study of Vedas. These are Siksha (Phonetics), Kalpa (Ritual), Vyakarana (Grammar), Nirukta (Etymology and Lexicology), Chanda (Prosody), and Jyotisha (Astrology and Astronomy). Two of these vidyas, Siksha (Phonetics) and Chanda (Prosody) are specifically meant to preserve the purity of the Vedas.

1. Siksha

Siksha, or Vedic Phonetics, is considered to be the most important vidya among the six Vedangas. It lays down the rules of phonetics and fixes precisely the method of pronunciation of the Vedas. The pronunciation is important because a small inflection in pronunciation can sometimes alter the meanings of the sentences. Siksha contains many methods to preserve the absolute purity of the word. They are known as Vaakya, Pada, Krama, Jata, Maala, Sikha, Rekha, Danda, Ratha, Ghana, etc. These methods are something like the error detection and correction algorithms used in modern messaging systems. They involve reciting each mantra in various patterns as specified by the methods, such as reciting it backward and forwards, breaking down the sentence into individual words, and reciting them in various combinations with the order of the words arranged in different patterns, etc. It takes 10 years for a student in the Vedic Pathashala to get the title of Ghanapati, one who can recite the Vedas correctly.

2. Chanda

Chanda is Prosody or Metrical Composition. It deals with the metrical and rhythmic aspects of chanting the Vedas. Whereas Siksha deals with the phonemes contained in the mantras, Chanda specifies the parameters for these phonemes, or phonetic pronunciations, to fall in place as poetry in metrical compositions. Chanda is a form of poetry and the term ‘Chanda‘ refers to the Veda itself as providing it with a distinction that differentiates it from ordinary Sanskrit. Chanda or meter provides the rhythm to the mantra. The rhythm also becomes an error-correction mechanism because a single mistake in pronunciation or intonation can break the rhythm of the poetry. Some of the meters which appear in the Vedas are Gayatri, Ushnik, Anushtup, Brihati, Pankti, Trishtup, Jagati, etc. As in the case of Siksha, Chanda too comes from the Vedas themselves. The Rishi who gave Chanda Sutras to the world is Pingala. Together, the two vidyas Siksha and Chanda ensure the purity of the Vedas. Thus, a Scripture that is Apaurusheya (first mark) and transmitted through a method that preserves the Purity of the Word (second mark) may qualify as flawless among all the scriptures found in the world.

FAULTLESSNESS: IS TRANSMISSION IN THE ENTIRETY NECESSARY?

Transmission has a purpose. The fundamental point is that the flaw in the transmission is determined by the purpose of the transmission. What is the purpose of transmitting the apaurusheya scripture? In modern messaging systems, we speak about information regarding particulars. In the scriptures, it is about knowledge regarding tattvas or universal principles. The one is related to information. The other is related to knowledge. So, given this nature of words, and given that the scriptures speak of universal principles, the importance of a transmission depends on the faithful transmission of the sentences that have these universal principles and not on the transmission of all the sentences that detail these universal principles in terms of particulars.

There are three aspects of the Vedas. Firstly, the sentences in scripture that contain the universal principles as their meanings are few. Secondly, the scriptures contain sentences that speak of the same principle from different approaches. For example, the Mandukya Upanishad speaks of the Supreme Truth by approaching it from the three states to the Fourth. There are sections in the Brahadaranyaka and Chandogya Upanishads that speak of the same Truth by approaching it from the non-difference of the effect from its material cause. Thirdly, the scriptures contain repetitions of the same Universal Principles in many different places in the scriptures.

The Vedas have an in-built mechanism to safeguard the transmission of the knowledge of the tattvas in the very body and structure of the scripture itself. There is no separate Vedanga to ensure complete transmission of the entirety of the Vedas unlike in the case of phonetic and tonal purity of the sound. Hence, for the transmission of the Apaurusheya Vedas, which transmit Knowledge of Universal Tattvas, the purpose is not dependent on the transmission of the entirety of the scripture.

THE QUESTION OF METHOD

The opposition to the Vedic tradition comes largely from those who espouse science. Unfortunately, a new system based entirely on modern science and European Renaissance ideas has replaced completely the traditional education. But it becomes vital for us to follow a method commensurate with Vedanta when we discuss Apaurusheyatva of the Vedas. When it comes to the acquisition of knowledge, ‘reason’ alone, a broad category, is an adequate tool. Science, for example, uses a specific reasoning method different from the reasoning methods used in philosophy. The central idea of science- physical causes alone can explain all things in nature, came from the Epicureans of Greece. Later, Francis Bacon (‘The Great Instauration’ and ‘Novum Organum’), Newton, and other scientists laid the foundation for the birth of science as we know it today.

In science, we begin with a proposition (a statement) that seeks to fit the facts of observed phenomena into a hypothesis. In doing so, the scientist uses reason to see that these facts fit logically into the meaning of the (propositional) statement. But science says further that this (propositional) statement must be physically verifiable. This is the key factor here. This principle of physical verifiability precludes the idea of there being any cause other than physical matter for the phenomena of the world. In contrast, there is no such constraint to philosophy by such ideas and its propositions have a different criterion of verifiability than conformance to physical verifiability.

It is necessary for us when discussing Vedanta, to consider the nature of the subject matter that we are dealing with. We are dealing here with a ‘Para Vidya’ in sharp contrast to every other science or discipline in the world grouped under the name of ‘apara vidya’. Science endeavors to throw light upon, among other things, how this universe originated and how life in the universe originated. Vedanta seeks to reveal a knowledge of a Truth by which billions and billions of cycles of creation and destruction are at once dissolved by an individual’s Self. When we seek to know the ‘truths’ revealed by science, we use elaborately constructed tools, but when it comes to the Supreme Knowledge of Vedanta, why do we become so blasé that we feel free to disregard the methods that it advocates?

THE TRAP OF MAYA

When we strive to obtain knowledge about an object, there are three factors involved in the process of obtaining knowledge: the subject, the object to be known, and the internal instrument by which the subject obtains knowledge of the object. In both Science and Western philosophy, the focus is entirely on knowing the object without regard to the nature of the internal instrument that we use to obtain knowledge.

In Vedanta, the situation is drastically different because it recognizes that avidya is the root cause of the jiva’s incapacity to obtain perfect knowledge. According to Advaita Vedanta, avidya influences the perception of the world. Mula-avidya, or the deep sleep that underlies the existence of a jiva, is avyakta or unmanifest. It is the darkness of sleep that one ‘sees’ when one is in deep sleep. It is the reason that when one wakes up from deep sleep, one says, ‘I knew nothing’. The ‘nothingness’ that one knew in deep sleep is the darkness that blocks the effulgence of the Self. By its essential nature, the Self is Self-effulgent with Consciousness. The deep sleep of the jiva obstructs the effulgence of the Self and presents the darkness of ‘nothing’. Even when a jiva wakes up, this sleep (bija-nidra) is present and everything that it perceives is through the veil of sleep. That is why when a man knows an object through perception, he still has the notion that he does not know it and builds theories to explain what the object is. But the object perceived is already known because pratyaksha, the valid means of knowledge for knowing the object, has revealed it.

The theories that one constructs to explain the object become superimpositions (adhyasa) on the object. In the words of Ludwig Wittgenstein, we look at the world through the nets of our theoretical constructs. Wittgenstein and his group in the field of Modern Analytical Philosophy tried to define a set of verifiability criteria for science. After striving for almost a decade, they abandoned the project. They recognized that the scientific propositions which form the initial working hypotheses of the scientists are already colored by the symbolic framework of science. Thus, was born the idea of ‘theory-ladenness of observation’. It is never possible for anyone to be completely free of theories when he or she looks at the world. Thus, the idea of our perceptions being colored by avidya is not a mere dogmatic assertion brought forth from the pages of Vedanta but a similar notion is indeed evident in the phenomenon of ‘theory-ladenness’. This then is the human predilection. The inner constitution of man is already colored by the darkness of avidya and it presents a matrix of circularity from which it is difficult to escape. To come back to the main point, the inner instrument of cognition needs to be free of defects if we are to obtain knowledge. There is no attempt either in science or in Western Philosophy to address this issue whereas, in traditional Indian Philosophy, it forms a major part of the effort to acquire knowledge.

THE MATRIX OF ACTION AND KNOWLEDGE

According to traditional Indian philosophies, the causal factors that give rise to inimical proclivities in the human mind and obstruct its strivings to obtain knowledge lie in the field of action. Even though the obtainment of knowledge is not dependent on action, action still plays a large part in the jiva’s struggle to attain knowledge. This is because it has a causal relation with the jiva’s condition which is the presence or absence of defects in the instruments of cognition. A jiva gets bound to ‘action’ only in the absence of Knowledge. This binding to action causes merits and demerits (from good and bad karmas) to arise. Unmeritorious actions lead to two things: (i) karma phala (fruits of past actions) in the form of suffering, and (ii) birth in a body that is suitable for the experience of the karma-phala. Bad karma, or unmeritorious action, leads to bodies possessing limitations and defects in the senses and instruments of cognition. In the presence of such defects in the instruments of cognition, knowledge cannot arise.

One obtains a defect-free instrument of cognition only through the performance of a set of actions that rectifies past defects and also prevents new defects. This two-fold set of actions to attain a defect-free condition results in chitta-shuddhi. In traditional Indian philosophy, this set of actions constitutes a life of ‘living by dharma’. In the pursuit of the four purusharthas known as kama, artha, dharma, and moksha, kama (pleasure) and artha (wealth and status) are acceptable but within the boundaries of dharma. It is only by living a life of dharma that a person goes towards the fourth purushartha, i.e., moksha. The human effort to obtain knowledge is thus a matrix involving both action and intellectual striving. With chitta-shuddhi, the effort at obtaining knowledge begins to bear fruit and the meanings of the scriptural statements begin to make sense. This is the stage of ‘adhikaara‘ when the person enters into the realm of epiphanic insight.

In Advaita Vedanta, the term ‘adhikaara’ is synonymous with the four qualifications comprising viveka (discrimination), vairagya (dispassion), sad-sampatti (six virtues), and mumukshutva (intense desire to attain liberation). Sri Shankaracharya categorically states that brahma-jignasa bears fruit only in the presence of the four qualifications. One who leads such a life that first establishes a pure mind through action and then a foundation to obtain Supreme knowledge is an Arya. Arya Dharma wholly directs to the ultimate goal of attaining the Supreme Knowledge even in those stages of a man’s life when the desire for kama and artha prevail in the heart. In Science and Western Philosophy, the pursuit of knowledge is an isolated activity. There is no recognition of the fundamental fact that the internal instrument for obtaining knowledge needs to be in a suitable condition. There are a few philosophies that recognize the imperative for action in the process of obtaining knowledge, such as those of Socrates and the Stoics, and in more recent times, the philosophy of Spinoza.

In Indian Philosophy, the pursuit of knowledge forms the central thread. Dharma has two forms known as pravritti and nivritti, the first pertaining to devotion to rightful action (karma-nishta) that seeks to make the condition suitable for knowledge to arise; and the second pertaining to devotion to knowledge (jnana-nishta) wherein the adhikari’s striving for knowledge bears fruit in the form of Supreme Knowledge. In the contemporary world, there exists a dichotomy between a body of knowledge called science in which the striving for knowledge is an isolated activity and a traditional body of knowledge in which the striving for knowledge forms an integral part of every sphere of human activity. In Vedanta, there is no such thing as a beginning to the process of acquiring knowledge. A jiva picks up from where he left off in a previous life and proceeds from there towards the goal.

To be continued…

Leave a Reply