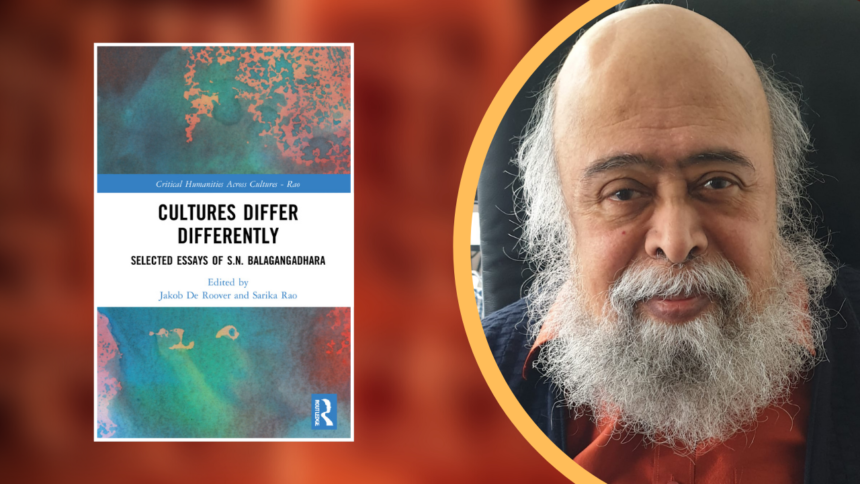

In this granular review, Dr Pingali Gopal summarises the key arguments of the anthology containing Dr SN Balagangadhara's arguments.

A review summary of Cultures Differ Differently: Selected Essays of S.N. Balagangadhara

Introduction

Dr SN Balagangadhara (Balu), one of the finest modern philosophers, has worked in the field of cultural studies at the University of Ghent for nearly four decades (Belgium). He was the India Platform’s and the Research Centre’s director (Comparative Science of Cultures).

He conveys the most intricate ideas, which can radically transform an interested reader, in a lucid manner that is accessible to all. The same text, which is immensely informative for a layperson, may possibly pave the way for further research in an academic institute. It is a unique talent to be able to compose academic papers in thriller prose.

Balu asks a critical question that forms the bedrock of most of his research program and that is: what if all the colonial descriptions of India are false and are solely the result of the knowledge of India generated by the colonial rule? Western intellectuals created specific theories and assumptions to look at other cultures which seem to have become the only way of looking at the world. Generations of Indian intellectuals bought as gospel European theories of social sciences and humanities. Indian traditions like Advaita, Buddhism, Jaina, Saiva, Vaishnava have also developed ingenious notions about human beings, societies, ethics, morals, ideals, politics, arts, and languages but there is gross ignorance of these. It is one of the greatest peculiarities of the huge corpus of Indian knowledge, based solely on indigenous experiences, to remain indifferent to the study of alien cultures. It betrays etiolation in our thinking.

The present book, Cultures Differ Differently, a collection of eight brilliant essays written at different periods of his research program starting in the 1980s, explains many of Balu’s ideas. For Balu, culture is fundamentally about the resources of socialization available for an individual and the community. Summarising some of the key ideas in the book, this article, from the perspective of a non-specialist reader, is an attempt to motivate a similar reader to engage with the book better.

Culture and Cultural Differences

Culture is a contentious subject, with over 164 definitions, some of which deny the concept entirely. According to Balu, the majority of linguistic and philosophical objections against the term “culture” stem from conceptual misunderstandings that do not necessitate rejecting the idea. According to Balu, these so-called flaws of the word “culture,” which are founded on a haphazard application of language and philosophy, are features of every and every word. Despite all of the negative connotations of the term “culture,” “cultural differences” has a lot of meaning and value. ‘Cultural differences’ can be climatological, biological, or psychological in nature, which is clearly distinct from the concept of ‘cultural differences.’ As a result, what creates a difference, particularly a cultural difference?

Human beings living in a group are socialized within the framework of groups. Their reservoir of learning contains the resources of the group- its customs, traditions, and institutions. Child-rearing, schooling, family life and group interactions are the mechanisms of transmission of these learning processes. In the process of learning (making a habitat) and ‘learning to learn’ (using the resources of socialization), a group builds its culturality. Culturalization thus becomes the way of both learning and teaching. Balu says that some difference between individuals is a cultural difference and not social, biological, or psychological in nature if it entails a specific way of using the resources of socialization.

Because of the great diversity of environments, dissimilarity in human nature and achievements, learning processes differ in different social groups. One learning process builds societies and groups; one creates poetry, music, and dance; and one develops theories and postulations. Different degrees and combinations of such learning processes lead to a common adaptive strategy in a specific group. In a social group, one dominant learning process subordinates other kinds of learning processes. A specific combination of dominant and subordinate learning processes makes up for a configuration of learning, and cultural differences are because of differences in these configurations. This is the strongest thesis of Balu while dealing with cultural differences. The West has a learning configuration rooted in religion where the ‘why’ question is important and this learning process generates theories and postulations. Indian culture abounds with rituals, which, in turn, build societies and groups. The ‘how’ question is important here.

Comparing Cultures-Why?

At an individual level, a person cannot be a typical ‘Indian’ or ‘Westerner’; but it is perfectly valid to describe cultural differences as they are real, observable, and empirically describable. Thus, these cultural differences emanate from differences in configurations of learning in different societies where there is an interplay between dominant and secondary modes of learning. Why, then, do we need to compare cultures?

Existing social sciences—primarily Western initiatives—have symbiotic ties with Orientalism or India studies. As they carry on the tradition of Orientalist works, today’s social sciences grow defective. In their statements about non-Western cultures, non-Western men, and their society, they mirror and buttress each other. Thus, in an unusual way, Indian intellectuals employing Western methodology view both the West and the East in the same way that Western intellectuals do. Balu laments the fact that our social sciences have been so colonised that the idea of how the world can look from our perspective is unsettling.

While studying India, the West problematized many narratives (Hinduism, caste, law, and so on), our social sciences did not question the older narratives but simply built on older theories by providing more ‘facts’. When Indian anthropologists, psychologists, or sociologists do their work, it is really the West talking to itself. We thus need to urgently decolonize the social sciences which should be a comparative exercise, taking off from the previous social science studies without rejecting the hard-won insights. This task of decolonizing should transcend the “us” versus “them” binary, emphasizes Balu.

Finally, the Orientalist account, despite appearing to be a description of other civilizations, is an oblique commentary on Western cultural experience, revealing the interpreter rather than the interpreted. We can thus study the describer’s (the West’s) culture through the medium of his descriptions (Orientalism), revealing the nature of Western civilization through cultural comparison.

By contesting a developmental ordering of history that places Western culture as the pinnacle of cultural development, comparative science aims to restore balance. Comparative studies seek to demonstrate that different cultures are distinct forms of life that confront one another as alternatives. Postcolonial studies are arbitrary, illogical, and unscientific. Comparative studies aim to propose rigorous theories in which the West and the East are treated equally.

Stories In Indian Culture

In western culture, stories may entertain and form a genre of literature but they do not instruct. Balu shows how stories constitute a differentiating point of our culture with many consequences. We never realize that the incredible variety and stock of stories for every situation in Indian culture play an important role in the socialising processes of a growing child. They work both as theoretical models representing small parts of the world and as practical exemplars which one can emulate. As theoretical models, stories are continuous with other learning products such as philosophy and scientific theories. Most importantly, without any explicit morals or methods of practical action, stories teach by the specific Indian cultural way of learning: mimetic learning. Mimetic learning or practical knowledge through exemplars creates new and original actions from old actions just as new ideas emerge from old ideas. Unlike in western culture where a moral principle needs to be context-free (applicable in all situations), an exemplar is always context-bound. However, they are generative of new actions in different contexts.

Mimesis and learning with exemplars are typical of the Asian (specifically Indian) culture where the most intriguing consequence is that instructional authorities need not be coextensive with religious, moral, political, or divine authorities. Balu explains how this mimetic learning by exemplars explains many things of Indian culture: the “strictness” of the family and the teacher in an individual’s life; the importance given to the relation between individuals presupposing a moral community; why immigrant Asians turn out to be better in mathematics and engineering than any other ethnic minority; the essentially conservative nature of India where tradition weighs heavily; and the resistance of the Indian ‘caste system’ to any centralisation of ‘political’ and ‘religious’ power.

About the practical action-knowledge unique to Indian culture, Balu says: “Unlike the natural world which is law-governed, a social world is the creation of human actions; the knowledge of creating it is the practical action-knowledge. Incredibly complex forms of social organisation can exist, continue to adapt themselves and expand without governance by any laws. A social organisation becomes an ‘accumulated’ practical knowledge. To seek to understand a social organisation by looking for its ‘laws’ might be as absurd as the denial of the law-governed character of the natural world. Spheres such as morality, law, social organisation, and human interaction belong to the realm of practical knowledge. Practical knowledge is cumulative, perhaps to a greater degree than knowledge in the theoretical sphere. The form of social organisation, the so-called ‘caste system’, is one such cumulative result. That is why no Indian could tell you what its ‘principles’ or ‘rules’ are. Yet, it reproduces itself because there is knowledge available (action-knowledge) to reproduce it. Its ability to ‘adapt’ itself to changing environments is merely the ability of human beings to execute actions in different environments.”

Cultural Differences in Morality

The fundamental categories that inform the description of the moral domain of other cultures arise from the describer’s culture. The notions of ‘selfhood’, the processes of learning, the experience of ‘body’, ‘space’ and ‘time’, and all other practices of community support and sustain a notion of the moral domain and moral practices. The basic conception of the ‘agent’ in Western culture is: in each human being, there exists an inner core (the Self or the agent) separable and different from everything else. In Indian culture, the actions which an individual performs constitute an agent and nothing more. The peeling of the outer layers in Western culture reveals the ‘true’ agent standing independent; in Indian culture, such peeling reaches an emptiness. This has extremely profound consequences in the domain of morality in Western and Indian cultures, says Balu.

We never finish learning about the world in any field, including morality, because the universe is complex. Western culture, obsessed with moral discussions, however never questioned their gospel that learning to be moral can have a terminus. Balu says that moral domain and contemporary ethical discussions, consisting of rules requiring a foundation, are secularised versions of theological commandments. Christianity admits only one Sovereign and His Will is the Law of the universe. ‘Being moral’ means obedience to this law because there are no other conceptions of (moral) Law and no other Sovereign. The terms in which the Christian religion and theology framed the question have ended up as things that are ‘definitionally true’ or ‘intuitively obvious’ to the practitioners of secular ethics including the ‘logical’ property of ‘moral’ statements—moral laws are made universalizable.

In Indian culture, one speaks of many sovereigns while speaking about morality. Consequently, an individual follows his ‘own’ morality; in this sphere, there is no one higher than the agent. The most fundamental category of ‘moral judgement’ in Indian traditions is that of appropriateness. Actions are meaningless (outside of contextual interpretations) and moral actions, as actions, become appropriate within contexts. As all the Indian traditions put it, performing an action without any desire, without aiming at any goal, and without attaching this intentionality to human action is always the highest appropriate action. It could well be an attitude that is beyond both good and evil.

Western culture, obsessed with morality, has executed atrocities that ‘ought’ to chill anyone’s blood: crusades, jihads, inquisitions, witch hunts, colonisation, genocide against American Indians, Nazism, and enslaving a continent and culture. According to Balu, it takes a tremendous amount of goodwill to consider the notion that these cultures are not inherently ‘evil.’ Tortures, conflicts, and cruelties are known in Indian civilization, but they are minor in comparison to the enormity of Western atrocities. As a result, the knife appears to cut both ways: against the backdrop of Western notions of ‘ethics,’ Indian traditions ‘chill the blood.’ The West appears immoral against the backdrop of Indian traditions.

Cultural Superimpositions and the Peculiarity of Indian Law

Balu shows in one of the essays how superimposing Western law on indigenous culture with their own ways of law and justice lead to severe distortions which we face today. There is a need for further studies on how law and culture relate and how we can evolve better legal systems. Balu thrashes to pulp the rhetoric about the great British law as a ‘gift’ to us. British society and law were corrupt to the core in the 18th and 19th centuries when they were ruling a great part of the globe. Their neighbours, allies, and cultural relatives saw them as corrupt, contemptible, hypocritical, and immoral. The British in India did whatever pleased them but the judges and bureaucrats clothed these acts in a legal language and many non-existent laws. Ironically, there was hardly equal justice in British India. Local European communities did not allow Indian judges and law officers to try them and they got away with the most brutal crimes through lenient European judges.

Balu then describes how modern Indians, assuming British law and institutions to be perfect, fused them with their own views about justice, truth, persons, and so on. The concepts of truth and falsity are fundamental in law. These ideas have their origins in Christian theology. There is a clear semantic distinction between lies and deception in Indian culture. Learning to lie is part of the socialisation process in Indian culture. Deception, on the other hand, is plainly distinct from lying. As a result, lying on oath loses its legal reasonings (ratio legis). Nonetheless, ‘perjury’ is still a punishable offence in Indian law.

As Balu explains, in western culture, it is the fair, objective, and impartial law that judges and not the person of the judge. In contrast, the Indian judiciary sees itself as the ‘embodiment’ of justice dispensing ‘justice’, often completely independent of, or even oblivious to, legal provisions and statutes. Even for many people going to court, the judge represents justice embodied and personified. This attitude helps us understand the massive corruption of the judiciary in India. Law in Western culture tries to reduce arbitrariness and capriciousness in settling disputes. But the imposition of the Western institutions in India encourages precisely that arbitrariness which law is supposed to prevent. The figure of the ‘judge’ now uses the legal institution, which gives him the power to do what he does, to make arbitrary pronouncements because of the culturally specific notion of the judge. In indigenous cultural institutions, reasonableness prevails because the judge faces the community directly and owes explanations. In modern courts, such constraints of reasonableness are absent.

Politics and law in Western culture are meant to further the general interests of society but not that of any single community, group, or individual, especially corporate interests. Strikingly, Balu says, Indian culture does not have a vocabulary to understand any discourse on interests- whether institutional, private, public, general, or social. If such is the case, legislation is meant to explicitly favour specific groups which would give them votes. The Parliament’s reasons, in implementing the laws, are not in the general interests of society but are as narrow as the reasoning of an individual who contemplates his own benefit. The British made laws that favoured British interests but cloaked them in the language of ‘general interest’ and ‘interest of the empire’. Protecting the British ‘interests’ later took the form of the ‘protection of minority interests’ in the Indian Constitution.

When the State promulgates laws that only favour and further narrow interests, citizens end up using such laws mostly retributively. Personal vengeance (dowry, atrocity, and so on) becomes the major if not sole goal of the citizenry when they go to the courts. Thus, when implemented in India, the institutions of Western law encourage a vengeful, spiteful, and ‘selfish’ citizenry. Instead of promoting a cohesive society, such laws encourage divisiveness and conflict in society. Our legal system needs a lot of deep thinking even as our judges are spreading out further in their extra-judicial activism and moral judgements on practically every institution in the country without looking into the mirror first.

The Problem with Translations

In the most vital chapter, Balu discusses the problems which arise from faulty translations to which Indologists, setting up powerful one-sided discourses, have been blind. Apart from the general issues of translating between two natural languages or between different domains in the same language, there are some unique problems that arise when one encounters cultural differences, especially in the domain of theology. In theology, till now, the decision process has only endorsed assumptions like (a) religion exists in all cultures; (b) each religion has specific ideas about ‘deity’, ‘sin’, ‘salvation’, etc.; (c) these religions are rivals of each other. Consequently, people were convinced that theological languages are mutually translatable and that the difference between these theologies lay in their content only: for centuries, the West believed that the Christian theological language was richer than the Indian theological language.

Balu makes it luculent how in the absence of native religions (like ‘Hinduism’, ‘Buddhism’ and ‘Jainism’), the terms from the theological language (formulated in English) cannot be translated either into Hindi or Sanskrit. Theological language has become a deep part of the natural language in the West that one has lost awareness that certain words (even words like ‘truth’ and ‘falsity’) are a part of specialised theories. Consequently, when Indians learn English, they map the technical meanings of theological vocabulary to words from their native languages and distort both English and the native language in the process. Colonial Consciousness, a colonial hangover continuing intellectual violence in contemporary times, finally generates an attitude that does not allow transmission of native theories about various aspects of human existence, unless first refracted through the prism of European reflections about ‘man and society’.

Indians, having access to Indian and European languages but not to the implicit ‘theories’ embedded in these languages and transmitted by these cultures, reproduce Western descriptions of India when studying India and her culture. Thus, unlike translations between European languages, we face specific problems that emerged because British colonialism occurred within the framework of cultural differences between the West and India, says Balu. By using two important statements in English which paved the way for many important domains in European culture (‘the grand book [of] the universe… is written in the language of mathematics’ by Galileo; and ‘Man was born free, and everywhere he is in chains’ by Jean-Jacques Rousseau), Balu shows that they make sense only in the Western world when accompanied by a cluster of ideas rooted in Christian theology. Indian cultural concepts of karma, moksha, cycles of birth, death, bondage, and so on make the assimilation of these statements into Indian traditions immensely problematic.

The Indologists/ Sanskritists and Social Sciences- A Death Dance for Knowledge

Regardless of what some scholars claim, Indology is not a viable path for the advancement of various domains (anthropology, sociology, and political science). Balu deconstructs the Indologists most effectively in the closing chapters. Some of these Indologists or Sanskritists who speak on Indian social structures, including caste, include Michael Witzel, Wendy Doniger, Brian Smith, Stephanie Jamison, and Joel Brereton. Contemporary social scientists cheerfully swallow the nonsense provided by Indologists and spin ridiculous stories about ‘Hinduism,’ ‘the caste system,’ and so on. In this large land with a time span of at least 3000 years, it is impossible to discover a single coherent ‘theory’ of varna in indigenous texts. However, scholars have based themselves on conjectures founded on fragmentary texts from 3000 or more years ago to speculate on the nature of Indian society. The infamous Manavadharmashastra or ‘Laws of Manu’, allegedly created by Brahmin priests seeking superior and privileged positions, makes Manu a ‘symbol of oppression’ today.

The 24th verse from the 10th chapter of Manusmriti aptly and famously articulates some of those constraints. The crucial word ‘vyabhicara’ translates as sexual misconduct in most English translations. However, this is in gross violation of the rules of Sanskrit grammar. In a verse with eight Sanskrit words, Balu shows how translators remove half the words present in the source, replace them with many words not present in the source, and exhibit the result as ‘translation’! Interpretations appear to precede the translation of text instead of the normal way. The end-goal focus (telos) of any translation is to show an iniquitous caste-ridden society with the wily Brahmins at the top. Moralising talk and a normative language (‘Inequality’, ‘discrimination’, ‘injustice’, and such other notions) define and determine the alleged talk about society, culture, and people blinding intelligent people to see through the charade.

Balu shows how one Indologist, Mikael Aktor, gathers evidence from the texts and commentaries across two thousand years having different historical and geographical origins to ‘show’ the varna ideology as existing across all centuries and prove that the Brahmins legitimised oppression.

In any other domain, his manner of dealing with texts would be faced with criticisms regarding methodology, chronology, methods of filtering very selective fragments, translation concerns, and problems with the nature, genre, transmission, redaction, and context of the quoted texts. However, as Balu writes: Instead, one leaves the chapter with the distinct impression that all these texts somehow represent the ‘Brahmanical ideology’ behind ‘the Hindu social structure’.

Indologists use discredited theories from earlier social sciences to put across outlandish claims regarding a culture about which they are ignorant. Contemporary social sciences draw upon these ignorant claims to put across equally outlandish claims about human societies and cultures, again in ignorance of what the Indological claims rest upon. Balu says sharply: “the social sciences and Indology enter a death dance where neither participant dies but knowledge does without delivering anything of substance about both Ancient and Modern India.”

The Indologists, Sanskritists, and the social scientists depending on each other deserve credit for accomplishing this incredible feat of making ‘the’ caste system synonymous with ‘discrimination’ and ‘oppression’ and so effortlessly superimpose the British ‘class’ hierarchy, American ‘racial’ inequality, the ‘apartheid’ policy, the Nazi ideology, and so on. Anthropologists spent about 100 years attempting to get rid of a pernicious and incoherent concept like ‘tribe’ only to see it sneak back in, via Indology and other social sciences, into the Indian Constitution, Indian legislation, and their administration. Balu concludes that the selling of ignorance as knowledge captures that nation’s academic philosophy and knowledge generation.

Concluding Remarks

The country must one day look at Balu for solutions. Maybe, it is still to sink to the deepest level to reach a point of hopelessness; only then we will hold the rope thrown by the Balu school, it seems. It may take many years, but Balu and his scholars have been working ceaselessly for decades for such a day with great hope. Adi Shankara finished and packaged his treatises a thousand to two thousand years ago not for his contemporary times but for the entire future till eternity. When an individual is in despair, he looks around to find Adi Shankara’s literature in place ready to receive him. Similar is the case with Balu; the only hope remains that such a state for the country does not come in a thousand years but in a few decades. But come it will.

Balu had his share of controversies; from ad hominem attacks on his ideas to even personal physical threats. All of them emanate from superficial reading, lack of understanding, and reluctance to seriously engage with him because most of his ideas radically kick a person from the comfort zones of easy, safe, and sometimes lazy scholarship. There has been a repeated accusation on Balu that he attributes excessive power to Western Christianity and even a laughable suggestion that he may be a covert Hindu fundamentalist. Nothing can be farther from the truth if one carefully goes through his books and articles. The alternative viewpoints are not attacks on Christ or Christians but simply arguments against secularized Christian theology dominating Indian intellectual discourse, causing immense damage to the social and cultural fabric of the country.

Through his arguments, he never abuses the West and always insists that the West and the East stand as equals and both have something to learn from each other. The only problem comes when one exclusive framework true for one culture tries to explain and understand all cultures and all humanity across time and space. Hence, he pleads for the East to develop its own paradigms and social sciences in a healthy manner to reverse the gazes. A reversal that leads to harmony rather than strife and violence which the present discourses continually seem to generate. Hence, when he attacks the West or Christianity or even Indian icons, it is only on the ideas and their violent consequences on Indian culture. Scratching the most superficial veneer of his apparently sharp language reveals an almost divine sage-like love for not only India but for all humanity. Balu’s outstanding essays and ideas offer hope to both professional academics concerned with rectifying the faulty discourses about India and laypeople who simply wish to see a better and more harmonious India.

Leave a Reply