The country’s so-called elite, whose mind had been shaped and hypnotized by their colonial masters, always assumed that anything Western was so superior that in order to reach all-round fulfilment, India merely had to follow European thought, science, and political institutions.

Effects of Colonization on Indian Thought – Part 1

Having suffered the burden of two centuries of British occupation, India has, since Independence, tried to come to terms with the impact of that exotic presence perhaps diametrically opposed to her own temperament, culture and genius. If anything, this introspection has only intensified in recent years, as Western culture (if it deserves this noble name) aggressively spreads around the globe. But it stands to reason that for an effective “decolonization” to take place—even in order to find out whether and how far it is desirable—we should first take a hard look at the effects of this colonization, what traces it has left on the Indian mind and psyche, and how deep.

Historical Background

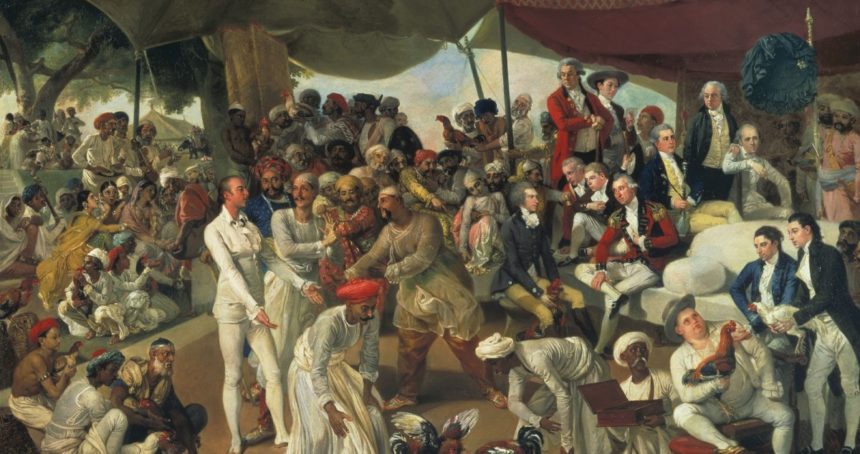

But first, an aside. I have only referred to the British occupation, not to the Muslim invasions, though they stretched over a much longer span of time and collided violently with Indian civilization. Yet, strangely, in spite of their ruthlessness, their proud and sustained use of violence to coerce or convert, India’s Muslim rulers never attempted to take possession of the Indian mind: in faithful obedience to Koranic injunctions, they simply tried to stamp it out. That they did not succeed is another story. The British, too, dreamed of stamping it out, but not through sheer brute force. As we know, besides their primary object of plunder, they viewed—or perhaps justified—their presence in India as a “divinely ordained” civilizing mission. They spoke of Britain as “the most enlightened and philanthropic nation in the world”[1] and of “the justifiable pride which the cultivated members of a civilised community feel in the beneficent exercise of dominion and in the performance by their nation of the noble task of spreading the highest kind of civilisation.”[2] Such rhetoric was constantly poured out to the Britons at home so as to give them a good conscience, while the constant atrocities perpetrated on the Indian people were discreetly hidden from sight.

To achieve their aim, the British rulers followed two lines: on the one hand, they encouraged an English and Christianized education in accordance with the well-known Macaulay doctrine, which projected Europe as an enlightened, democratic, progressive heaven, and on the other hand, they pursued a systematic denigration of Indian culture, scriptures, customs, traditions, crafts, cottage industries, social institutions, educational system, taking full advantage of the stagnant and often degenerate character of the Hindu society of the time. There were, of course, notable exceptions among British individuals, from William Jones to Sister Nivedita and Annie Besant—but almost none to be found among the ruling class. Let us recall how, in his famous 1835 Minute, Thomas B. Macaulay asserted that Indian culture was based on “a literature … that inculcates the most serious errors on the most important subjects … hardly reconcilable with reason, with morality … fruitful of monstrous superstitions.” Hindus, he confidently declared, had nothing to show except a “false history, false astronomy, false medicine … in company with a false religion.”[3] As it happened, Indians were—and still largely are—innocent people who could simply not suspect the degree of cunning with which their colonial masters set about their task. In the middle of the 1857 uprising, the Governor-General Lord Canning wrote to a British official:

As we must rule 150 millions of people by a handful (more or less small) of Englishmen, let us do it in the manner best calculated to leave them divided (as in religion and national feeling they already are) and to inspire them with the greatest possible awe of our power and with the least possible suspicion of our motives.[4]

Even a “liberal” governor such as Elphinstone wrote in 1859,

“Divide et impera [‘divide and rule’ in Latin] was the old Roman motto and it should be ours.”[5]

In this clash of two civilizations, the European, younger, dynamic, hungry for space and riches, appeared far better fitted than the Indian, half decrepit, almost completely dormant after long centuries of internal strife and repeated onslaught. The contrast was so huge that no one doubted the outcome—the rapid conquest of the Indian mind and life. That was what Macaulay, again, summarized best when he proudly wrote his father in 1836:

Our English schools are flourishing wonderfully…. It is my belief that if our plans of education are followed up, there will not be a single idolater among the respectable classes in Bengal thirty years hence.[6]

But if there is one thing that the British could not understand about Indians, it is that they live more in the heart than in the mind. And that heart the rulers could never touch or influence, especially not with their shallow religion or science. As for the mind, they did succeed in creating a fairly large “educated” class, anglicized and partially Christianized, which always looked up to its European model and ideal, and formed the actual foundation of the Empire in India. Came Independence. If India did achieve political independence—at a terrible cost and by amputating a few limbs of her body—she hardly achieved independence in the field of thought. Nor did she try: the country’s so-called elite, whose mind had been shaped and hypnotized by their colonial masters, always assumed that anything Western was so superior that in order to reach all-round fulfilment, India merely had to follow European thought, science, and political institutions. Swami Vivekananda was the first to give this call: “O ye modern Hindus, de-hypnotise yourselves!” [7]

The Symptoms

A hundred years later, at least, we can see how gratuitous those assumptions were. Yet the colonial imprint remains present at many levels. On a very basic one, it is almost amusing to note that Pune is sometimes called “the Oxford of the East,” while Ahmedabad is “the Manchester of India”—and since Coimbatore is often dubbed “the Manchester of South India,” we have at least out-Manchestered England herself ! The Nilgiris are flatteringly compared to Scotland (never mind that Kotagiri, where I live, is called “the second Switzerland”), and I understand that tourist guides refer to your own Alappuzha as “the Venice of the East.” Pondicherry, also to attract tourists, calls itself “India’s Little France” or “the French Riviera of the East.” India’s map seems dotted with European places. And “east” of what, incidentally? This is something like India’s learned “Oriental” institutes—what “orient” do they refer to? Thailand or Japan, perhaps? Things become more troublesome when Kalidasa is called “the Shakespeare of India,” when Bankim Chatterji needs to be compared to Walter Scott or Tagore to Shelley, and Kautilya becomes India’s very own Machiavelli. We begin to see how our compass is set due west. Would the British call Shakespeare “England’s Kalidasa,” let alone Manchester “the Coimbatore of Northwest England”?

But I think the most alarming signs of the colonization of the Indian mind are found in the field of education. Take the English nursery rhymes taught to many of our little children, as if, before knowing anything about India, they needed to know about Humpty-Dumpty or the sheep that went to London to see the Queen. When they grow older, some of them will be learning Western psychology while remaining totally ignorant of the far deeper psychology offered by Yoga, or they will study medicine or physics or evolution without having the least idea of what ancient India achieved – and often anticipated – in those fields. Which teacher, for example, will tell his or her students that Darwinian evolution was always at the back of the Indian mind, as the sequence of the Dashavatar shows? Or that the speed of light is clearly given, to an amazing degree of precision, in Sayana’s commentary on the Rig-Veda?[8] And can it be a coincidence if a day of Brahma, equal to 4,320,000,000 years, happens to be the age of the earth? Many such examples could be supplied in other fields, from mathematics and astronomy and quantum physics to linguistics and metallurgy and urbanization.[9] If teachers were not so ignorant, as a rule, of their own culture, they would have no difficulty in showing their students that the much-vaunted “scientific temper” is nothing new to India.

Even in medicine, we know how Ayurveda and Siddha systems of medicine have been neglected under the illusion that modern medicine is the only way to provide “health for all.” Our educational policies systematically discourage the teaching of Sanskrit, and one wonders again whether that is in deference to Macaulay, who found that great language (though he confessed he knew none of it) to be “barren of useful knowledge.” In the same vein, the Indian epics, the Veda or the Upanishads stand no chance, and students will almost never hear about them at school. Even Indian languages are subtly or not so subtly given a lower status than English, with the result that many deep scholars or writers who chose to express themselves in their mother-tongues (I have of course N. V. Krishna Warrior in mind) remain totally unknown beyond their States, while textbooks are crowded with second-rate thinkers who happened to write in English.

If you take a look at the teaching of history, the situation is even worse. Almost all Indian history taught today in our schools and universities has been written by Western scholars, or by “native historians who [have] taken over the views of the colonial masters,”[10] in the words of Prof. Klostermaier of Canada’s University of Manitoba. All of India’s historical tradition, all ancient records are simply brushed aside as so much fancy so as to satisfy the Western dictum that “Indians have no sense of history.” Indian tradition never said anything about mysterious Aryans invading the subcontinent from the Northwest, but since nineteenth-century European scholars decided so, our children still today have to learn by rote this invention now rejected by most archaeologists; South Indian tradition said nothing about the Dravidians coming from the North, driven southward by the naughty Aryans, but again that shall be stuffed into young brains. No Indian scholar or grammar or tradition ever claimed that Sanskrit and Tamil languages were great rivals belonging to wholly separate families, but this shall be taught at school in deference to Western linguists or to our own “Dravidian” activists.

The real facts of the destruction wreaked in India by Muslim invaders and also by some Christian missionaries must be kept outside textbooks and curricula, since they contradict the “tolerant” and “liberating” image that Islam and Christianity have been projecting for themselves.[11] Even the freedom movement is not spared: as the great historian R. C. Majumdar[12] and others have shown, no serious, objective criticism of Mahatma Gandhi or the Indian National Congress is allowed, and the role of other important leaders is systematically belittled or erased. Nothing illustrates the bankruptcy of our education better than the manner in which, just a year ago, State education ministers raised an uproar at an attempt to discuss the introduction of the merest smattering of Indian culture into the syllabus, and at the singing of the Saraswati Vandana. * The message they actually conveyed was that no Indian element was tolerable in education, while they are perfectly satisfied with an education that, at the start of the century, Sri Aurobindo called “soulless and mercenary,”[13] and which has now degenerated further into a stultifying, mechanical routine that kills our children’s natural intelligence and talent. They find nothing wrong with maiming young brains and hearts, but will be up in arms if we speak of teaching India’s heritage. Ananda Coomaraswamy, the famous art critic, gave the following warning early this century:

It is hard to realize how completely the continuity of Indian life has been severed. A single generation of English education suffices to break the threads of tradition and to create a nondescript and superficial being deprived of all roots—a sort of intellectual pariah who does not belong to the East or the West, the past or the future. The greatest danger for India is the loss of her spiritual integrity. Of all Indian problems the educational is the most difficult and most tragic.[14]

Swami Vivekananda had earlier said much the same thing in his own forthright style:

The child is taken to school, and the first thing he learns is that his father is a fool, the second thing that his grandfather is a lunatic, the third thing that all his teachers are hypocrites, the fourth, that all the sacred books are lies ! By the time he is sixteen he is a mass of negation, lifeless and boneless. And the result is that fifty years of such education has not produced one original man in the three presidencies…. We have learnt only weakness.[15]

The child becomes a recording machine stuffed with a jarring assortment of meaningless bits and snippets. The only product of this denationalizing education has been the creation of a modern, Westernized “elite” with little or no contact with the deeper sources of Indian culture, and with nothing of India’s ancient view of the world except a few platitudes to be flaunted at cocktail parties. Browsing through any English-language daily or magazine is enough to see how Indian intellectuals revel in the sonorous clang of hollow clichés which, the world over, have taken the place of any real thinking. If Western intellectuals come up with some new “ism,” you are sure to find it echoed all over the Indian press in a matter of weeks; it was amusing to see how, some two years ago, the visit to India of a French philosopher and champion of “deconstructionism” sent the cream of our intellectuals raving wild for weeks, while they remained crassly ignorant of far deeper thinkers next door.

Or if Western painters or sculptors come up with some new-fangled cult of ugliness, their Indian counterparts will not lag far behind. If Western countries plan grand celebrations for the “millennium” (not a third millennium of darkness, one hopes), we in India follow suit—though we appear to have forgotten to celebrate the fifty-second century of our Kali era earlier this year. And let “politically correct” Western nations make a new religion of “human rights” (with intensive bombing campaigns to enforce them if necessary), and you will hear a number of Indians clamouring for them parrotlike. The list is endless, in every field of life, and if India had been living in her mind alone, one would have to conclude that India has ceased to exist—or will do so after one or two more generations of this senseless de-Indianizing. In Sri Aurobindo’s words: … Ancient India’s culture, attacked by European modernism, overpowered in the material field, betrayed by the indifference of her children, may perish forever along with the soul of the nation that holds it in its keeping.[16]

Continued in Part 2

References:

[1] Rev. John Wilson, India Three Thousand Years Ago, quoted by Devendra Swarup in “Genesis of the Aryan Race Theory and Its Application to Indian History,” The Aryan Problem, eds. S. B. Deo and S. Kamath (Pune: Bharatiya Itihasa Sankalana Samiti, 1993), p. 33-35.

[2] Sidgwick, quoted by Sri Aurobindo in Bande Mataram of 19 June 1907: see India’s Rebirth (Mysore: Mira Aditi, 2000), p. 24.

[3] In British Paramountcy and Indian Renaissance, vol. 10 in The History and Culture of the Indian People (Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1991), p. 83-84.

[4] Quoted by P. Hardy in The Muslims of British India, p. 72.

[5] In British Paramountcy and Indian Renaissance, p. 321.

[6] Quoted by N. S. Rajaram in The Politics of History (New Delhi: Voice of India, 1995) p. 105.

[7] Swami Vivekananda, Lectures from Colombo to Almora (Calcutta: Advaita Ashram, 1992), p. 105.

[8] See for example P. V. Vartak, Scientific Knowledge in the Vedas (Delhi: Nag Publisher, 1995) ; Subhash Kak, “Sayana’s Astronomy” (Indian Journal of History of Science, vol. 33, 1998, p. 31-36).

[9]See for example A Concise History of Science in India, eds. D. M. Bose, S. N. Sen & B. V. Subbarayappa (New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy, 1989) ; History of Technology in India, ed. A. K. Bag (New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy, 1997); History of Science and Technology in Ancient India, by Debiprased Chattopadhyaya (Calcutta: Firma KLM, 3 vols., 1986, 1991, 1996); Computing Science in Ancient India, eds. T. R. N. Rao & Subhash Kak (Louisiana: Center for Advanced Computer Studies, 1998).

[10] Klaus Klostermaier, “Questioning the Aryan Invasion Theory and Revising Ancient Indian History,” in Iskcon Communications Journal 1999.

[11] See for example Arun Shourie, Eminent Historians (New Delhi: ASA, 1998) and Missionaries in India (New Delhi: ASA, 1994); Sita Ram Goel, History of Hindu-Christian Encounters (New Delhi: Voice of India, 1997) and Hindu Temples—What Happened to Them (New Delhi: Voice of India, 2 vols., 1998, 1993).

[12] See R. C. Majumdar, History of the Freedom Movement in India (Calcutta: Firmal KLM, 3 volumes, 1988), in particular Appendix to vol. 1 and Preface to vol. 3. See also N. S. Rajaram, Gandhi, Khilafat and the National Movement (Bangalore: Sahitya Sindhu Prakashana, 1999).

[13] Sri Aurobindo, “The National Value of Art,” in Karmayogin, 20 November 1909, in India’s Rebirth, p. 65.

[14] Ananda Coomaraswamy, The Dance of Shiva (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1997), p. 170.

[15] Swami Vivekananda on India and her Problems (Calcutta: Advaita Ashram, 1985), p. 38-39. [16] Sri Aurobindo, India’s Rebirth, p. 139 (emphasis mine).

Leave a Reply